Even a passing familiarity with a Christian reading of the Old Testament reveals a series of prophetic elements that, from that Christian reading, point to fulfillment in the person of Jesus Christ. These prophetic elements, however, often seem disparate and scattered. There are prophecies of the defeat of death, the downfall of the devil, the restoration of the nations, the overcoming of sin, a prophet like Moses, God’s arising to judge the earth, and countless others of more or less detail. By the time period reflected by the Gospels and other New Testament writings, however, all of these promises seem to have coalesced around the person of the coming Messiah or Christ. Christ’s identity as the Messiah is the explicit focus of the Gospels. The remaining writings of the New Testament consistently refer to Jesus as simply ‘Christ’ over and over again, a constant reminder that he is, in fact, the Messiah and that that identification forms the basis of all of the other statements regarding him made by the apostles. This is not an odd development that takes place “between the Testaments.” Rather, the focus of all of these prophecies around a single person is something that occurs within the pages of the Hebrew Bible itself. It is reflected in the apostolic writings because it was a part of their religion within the Second Temple period.

Even a passing familiarity with a Christian reading of the Old Testament reveals a series of prophetic elements that, from that Christian reading, point to fulfillment in the person of Jesus Christ. These prophetic elements, however, often seem disparate and scattered. There are prophecies of the defeat of death, the downfall of the devil, the restoration of the nations, the overcoming of sin, a prophet like Moses, God’s arising to judge the earth, and countless others of more or less detail. By the time period reflected by the Gospels and other New Testament writings, however, all of these promises seem to have coalesced around the person of the coming Messiah or Christ. Christ’s identity as the Messiah is the explicit focus of the Gospels. The remaining writings of the New Testament consistently refer to Jesus as simply ‘Christ’ over and over again, a constant reminder that he is, in fact, the Messiah and that that identification forms the basis of all of the other statements regarding him made by the apostles. This is not an odd development that takes place “between the Testaments.” Rather, the focus of all of these prophecies around a single person is something that occurs within the pages of the Hebrew Bible itself. It is reflected in the apostolic writings because it was a part of their religion within the Second Temple period.

From the very beginning of the gospel promise, in the curse placed upon the Devil when he was cast down to the underworld as humanity was expelled from paradise, the promise is tied to a particular person who is human (Gen 3:15). Even as the devil is given the power of death, it is spoken that he will be defeated and deprived of that power beneath the foot of the seed of the woman (Gen 3:14; Heb 2:14). It is an oddity that here, the seed is described as that of the woman, rather than as of Adam. The latter would have reflected the later usage of the title “Son of Man” within the Hebrew Bible. The prophetic significance of this identifier would continue to play out within Scripture to be fulfilled in the virgin birth of Christ (eg. Jer 31/38:22; Gal 4:4). The defeat of the devil and the immortality of humanity will come about through this prophesied seed.

After two further supernatural and human rebellions, the next statement of the gospel hope comes in the promises to Abraham. These promises are focused around Abraham’s descendants becoming like the stars of the heavens, the angelic host. This will happen through the defeat and overthrow of the gods of the nations, fallen spiritual beings, and their replacement which will be a blessing to all of the nations. What connects these promises to the previous promise is that these promises will be brought to fruition through Abraham’s seed. The Hebrew noun translated as “seed,” tzera, is a collective noun. This means that it can be either singular or plural depending on the context, like the English words “deer” or “fish.” In Greek translations, however, beginning with Genesis as translated by the Seventy, it was translated in the context of the promises to Abraham in the singular. This indicates that from at least the third century BC, it was understood to be referring to a particular person, the same person referred to in Genesis 3. St. Paul points directly to this Greek translation in order to make his point regarding the Messiah as the agent who fulfills these promises (Gal 3:16).

The promise of this coming person is further defined in the testament of Israel. In Genesis 49, Jacob prophetically blesses his 12 sons, though several of these blessings sound more like curses. The prophecy concerning Judah, or rather one of Judah’s descendants, a “seed,” is critically important. It is here, in Genesis 49:8-12, that kingship is first directly applied to this figure of the “seed.” It is through this descendant of Judah that the enemies are defeated (v. 8-9). He will rule immediately over the tribes of Israel (v.8), but ultimately over all the nations (v. 10). Often, this is interpreted as referring to the Davidic monarchy as such. In an immediate sense, it is, yet it points beyond that immediate fulfillment to an ultimate one. It is sometimes unclear in English translations of verse 10 because most English translations follow the much later re-vocalization (rearrangement of vowels) by Rabbinic Judaism which causes the verse to read that the scepter will not depart from him until he “receives tribute.” All of the ancient translations, however, including those which are considered pre-Christian, the Greek, the Aramaic, and the Syriac, understand the verse as reading that it will not depart from him until “he comes to whom it belongs.” Given as a prophetic sign of this one is that he will bind his colt to the vine and his donkey to the choice vine (v. 11; cf. Zech 9:9; Matt 21:2; Mark 11:4).

The identifier of this person as Messiah or Christ, as the anointed one, is primarily a reference to him as this king. Many people have been taught that kingship is not a concept found within the Torah. They have been taught that in some sense, Israel was not “supposed to” have a king. This, however, is a misunderstanding of the teaching of the Scriptures. Within the Torah, the institution of the monarchy is already discussed. Prophetically, Moses states that once they are settled in the land, Israel will say that they want to set a king over themselves like their neighboring nations have (Deut 17:14). They are, however, to wait for the king of Yahweh’s choosing (v. 15) and not to choose one for themselves or bring themselves under the rule of a foreigner. After making this statement regarding a king of Yahweh’s choosing coming for whom they should wait, commandments are given which would place restrictions upon human kings, anticipating that there would be other kings in addition to his chosen. These kings are not to take many wives, not to accumulate armies and material power, and not to seek after vast wealth (v. 16-17). Positively, these kings are to make for themselves a copy of the Torah to study and meditate upon it so that they may be faithful and their dynasties may endure (v. 18-20). The mention of dynasties here clearly distinguishes these kings from the “seed” of Genesis though the latter is implied to be the king of Yahweh’s choosing.

When Israel’s monarchy is discussed, the most often referenced portion of Scripture is 1 Samuel/1 Kingdoms 8, in which Israel’s demand for a king is treated as a sinful rejection of Yahweh as their God. At first glance, this appears to contradict the trajectory established in the Torah in general and Deuteronomy’s statements regarding the monarchy in particular. A careful reading of the portrayal of these events in the life of the prophet Samuel, however, reveals exactly where the sin lay. At this point, Samuel was the judge of Israel, was of advanced age, and had appointed his sons to judge Israel after him. The difference between this state of affairs and the initial request of the men of Israel, that they have a king who judges them and who would presumably be succeeded by their own son, seems somewhat academic (1 Sam/1 Kgdms 8:1-5). Further, Deuteronomy 17:14 had already stated that they would have this desire with no attached opprobrium. Initially, the only possible problem would seem to be that they are not waiting for the king whom Yahweh would send.

After Samuel’s attempt to dissuade the people, however, when the demand is reiterated in greater detail, the central problem becomes apparent. They not only want to be judged by a king, rather than someone without that title. They want a king who will lead them into battle against their earthly enemies (1 Sam/1 Kgdms 8:19-20). From the Exodus until that very day, it had been Yahweh himself who led them into battle and to whom they were to be faithful to have victory over their enemies. They were, therefore, quite literally putting their trust in a human prince rather than in their God. In a very real way, they were rejecting the authority of Yahweh in favor of human authority. They desired to be one of the nations, rather than the special possession of the God of Israel. When this text is taken in the context of what has preceded it, however, another important point emerges. The God of Israel has already promised the coming of a king who will be victorious over the enemies of humanity. This king, then, the king of Yahweh’s choosing will lead his people into battle and that idea is not opposed to Yahweh himself leading them into battle. The coming king will not only be in some sense divine, which all of the nations thought concerning their kings but will be in some sense Yahweh himself.

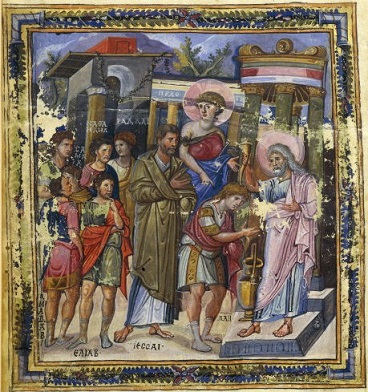

After Saul, who in many ways represents God’s judgment against the pride of the kings of the nations, David becomes king of Israel and serves as an icon of the one who will come. This became so firmly embedded in the minds of the Judean people that the Messiah was frequently simply referred to as “David” or “the son of David” throughout the Second Temple period (eg. Matt 9:27; 12:23; 15:22; 20:30-31; 21:9, 15; 22:42; Mark 10:47-48; 12:35; Luke 18:38-39). Nevertheless, David was understood to the image of the one to come and not identical, nor were the prophecies just about David and his dynastic line (eg. Luke 20:41-44; Acts 2:29, 34; 13:36). Important in this understanding of David as the icon of the coming Messiah is the shape of David’s life as a whole. David spent much of his life on the run, suffering persecution for the sake of righteousness, and rejected by his own people. He was betrayed by his closest allies and family members. In two great cycles over the course of his life, David suffered exile, homelessness, and rejection before entering into glory through first his coronation and then the restoration of his reign (cf. Luke 24:26). This led ancient interpreters to understand the “Suffering Servant” of Isaiah 53 to be the Messiah. The Rabbinic understanding of the Suffering Servant as Israel is a radically new thing. As late as Maimonides in the 12th century AD, Jewish interpreters understood this figure to be the promised Messiah.

The royal court of David and his descendants also served as an icon of the divine council. This is true in two senses. First, in that David and his descendants as kings were to represent the justice and reign of Yahweh, the God of Israel on earth. Second, in a prophetic sense as the seed of the woman, the seed of Abraham, the king from Judah, is also the son or seed of David. This latter understanding is important vis a vis the institution of gebirah, or queen-mother, within Judah. The promise received by David concerning his line makes this clear in the differing ways in which it is worded in the two accounts given of these promises in the Hebrew Scriptures. Its earlier recording states that God will establish David’s house and kingdom and throne forever (2 Sam/2 Kgdms 7:16). Its later, post-exilic, recording states that Yahweh will establish the son of David in the God of Israel’s own house and kingdom and on his throne forever (1 Chron 17:14). This is not a contradiction but an interpretation. In the person of the Christ, the throne of David will be united to the throne of God. The kingdom of this world will become the kingdom of God. For this to happen, once again, the coming king must be human and also Yahweh. In comparison to this king, David is here described as a prince (2 Sam/2 Kgdms 7:8; 1 Chron 17:7).

The most quoted Old Testament text in the New Testament is Psalm 110/109. Its first verse is taken to make this Psalm the paradigmatic Messianic prophecy, “Yahweh said to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool'” (v. 1). This prophecy, attributed to David himself, speaks to a co-regency of the human Messiah with Yahweh, the God of Israel. This enthronement of the human Messiah is approached in the opposite direction by the prophet Daniel. In a correction and reworking of the scene of the enthronement of Baal by his father El, Daniel describes a vision of a divine figure who appears human, the Son of Man, who is enthroned by Yahweh the Father (Dan 7:13-14). Within the understanding of those within the Second Temple period, this confirmed that the Messiah and the Son of Man were the same figure. The “seed” who would come to win victory over the devil, death and the evil spiritual powers who had enslaved the nations to establish his kingdom over the whole creation would be both divine and human. He would both be descended from Adam, Abraham, and David (Matt 1:1; Luke 3:31, 34, 38) and be Yahweh himself.

What it meant for the second person of Yahweh to also be human would be the subject of debate for centuries before and after the time of Jesus within Jewish and Christian communities. In fact, these debates would run roughly in parallel in both Christian and non-Christian Jewish circles. But this element of the Messianic identity was the subject of wide acceptance. This is why the Christ was also considered to be the Holy One of God (Mark 1:24; Luke 4:34; John 6:69), a title otherwise reserved for Yahweh himself in the Hebrew Bible (eg. Ps 71/70:22; 78/77:41; Is 29:23; 30:15; 43:3; 48:17; 60:9; Jer 51:5; Hos 11:12; Hab 3:3). The addition of the defining “of God” serves to indicate that this second person of Yahweh is one with God the Father.

It is often argued that Jesus of Nazareth did not fit the “Jewish” criteria for the Messiah at the time of his coming in the first century AD. This is literal nonsense. The New Testament writers were not playing fast and loose with Messianic prophecies or finding them in the Hebrew Scriptures where they had not been hitherto found. Their understanding of the Christ who was to come was well within the mainstream understanding of faithful Judeans scattered throughout the world. This included the understanding that Jesus’ poverty, homelessness, and widespread rejection were anticipated by the life of David. The obstacle, or stumbling block, was the cross itself which seemed to be an image of defeat rather than victory. And it only seemed to be a defeat until, illuminated by the light of the resurrection, the victory of Christ related in the gospel of Jesus Christ was made plain.

Thank you Father,

It is good to learn about Holy Scripture from someone who, not only have study it, but also lives it.

There are so many poor translations around today, at least in English, so to get an in depth study linking all Scripture, is much needed.

Fr. Stephen, I’m sure all appreciate the effort you make to bring together the continuity of the scriptures, I certainly do. I have a question regarding how the rabbinical judeans respond to the clear changing of the scriptures in certain (important) instances, probably the best of which is located in Psalm 21/22. Do they really have an even remotely believable counter to that matter, given the presence of extant DSS, Septuagint, older manuscripts, etc? Thanks for your time and keep up the good work.

While the accusations of change are there from a very early period, when we look at the complete picture, at least as we have it, from the ancient period it is more complex than that. The DSS, for example, had Hebrew manuscripts that match both the MT and Greek versions of Jeremiah. They had these side by side. The DSS have pretty well proven that there were, at least in the Second Temple period, multiple strands of Hebrew text tradition. One of these is reflected by the Greek manuscript tradition. One, referred to as the proto-MT, corresponds more directly to the Masoretic Text. So it’s less a case of change and more a case of Christianity and later Rabbinic Judaism having followed different strands of the Hebrew scriptural tradition. The fact that that included Rabbinic Judaism repudiating the portion of the tradition embraced by Christianity is what opened up the accusations of deliberate change and meddling.

Fr. Stephen, I thought Jesus was headquartered in Capernaum. On what do you base the idea that he was homeless?

St. Peter had a family home in Capernaum, but only a portion of Christ’s ministry was in Galilee, let alone in Capernaum itself. Christ spent his earthly ministry moving from place to place being hosted and receiving hospitality from others. Matt 8:20/Luke 9:58 is on point here.

Thank you so much. I am learning much from your blogs.