In preparing his Latin translation of the scripture, St. Jerome translated the Greek word “diatheke” and the Hebrew word “berith” with the Latin “testamentum.” From the latter word, the English word “testament” is derived. The original Hebrew term, “berith,” refers most commonly to treaty documents, and in its usage in the Torah particularly refers to a particular type of treaty, that issued by a suzerain to a vassal at a king’s accession to the throne. This usage is in view in the New Testament in every instance of its usage but one. To convey this usage, the word is generally translated “covenant.” The translators of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek translated the word with the Greek “diatheke” which is likewise flexible, referring to a broad range of legal documents, but which includes the original usage. The Latin term “testamentum” means literally a “thing witnessed.” This term can likewise cover a broad range of legal documents, essentially anything to which the testimony of witnesses was attached. Deliberately or not, St. Jerome chose a term which conveyed both the idea of covenant and the Greek concept of “martyria.” or witness, especially important in its use for the two primary divisions of the scriptures, the “Vetus Testamentum” and the “Novum Testamentum.”

In preparing his Latin translation of the scripture, St. Jerome translated the Greek word “diatheke” and the Hebrew word “berith” with the Latin “testamentum.” From the latter word, the English word “testament” is derived. The original Hebrew term, “berith,” refers most commonly to treaty documents, and in its usage in the Torah particularly refers to a particular type of treaty, that issued by a suzerain to a vassal at a king’s accession to the throne. This usage is in view in the New Testament in every instance of its usage but one. To convey this usage, the word is generally translated “covenant.” The translators of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek translated the word with the Greek “diatheke” which is likewise flexible, referring to a broad range of legal documents, but which includes the original usage. The Latin term “testamentum” means literally a “thing witnessed.” This term can likewise cover a broad range of legal documents, essentially anything to which the testimony of witnesses was attached. Deliberately or not, St. Jerome chose a term which conveyed both the idea of covenant and the Greek concept of “martyria.” or witness, especially important in its use for the two primary divisions of the scriptures, the “Vetus Testamentum” and the “Novum Testamentum.”

The English word “testament,” on the other hand, does not carry with it the larger understanding of “covenant.” Its most common usage is in the phrase “last will and testament” in which “testament” refers to the portion of the document in which the person disposes of their personal property after their death. Because of this, the King James translators, for example, maintained the headings of Old and New Testament for the divisions of the scriptures with the Latin term’s double meaning, but translated the word in the text of the scriptures as “covenant.” The English word “testament” has since found an entirely different use in regard to Biblical literature based on its English usage. There is a vast swathe of Jewish literature from the Second Temple period which falls under the genre of “testaments.” There are written testaments for a vast swathe of Biblical figures, the most important of which, for its apparent influence on the New Testament, is collectively called “The Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs.” This is actually a collection of texts, one testament for each of the sons of Jacob. These texts have been preserved by the Church at many ancient monastic foundations, particularly St. Catherine’s, Mar Saba, and Mt. Athos.

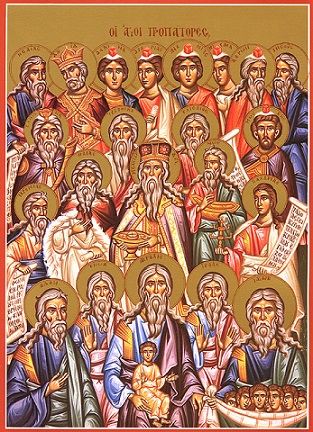

All of these testaments present the Biblical figure in question expressing his final words and wishes shortly before his death. In many cases, these words have a prophetic focus, describing future events. Several of them verge into apocalyptic. This genre is based on a particular Biblical text, Genesis 49. In this text, Jacob gathers his sons after they have been reunited in Egypt and speaks to them his final words from his deathbed before going to rest with his fathers. The text describes what he says to each of his sons as “a blessing” which is appropriate to them, though many are quite negative in their outlook. In most instances, they seem clearly directed toward the tribe which would descend from that patriarch, rather than the person of Jacob’s son. While it is sometimes obscured in modern translations, which render the phrase “sons of Israel” as “children of Israel,” this collective phrase when used for the nation of Israel is actually a reference to the unity of the 12 tribes. Referring to the nation as the “United States” has a similar resonance. Jacob had sons of his loins, but also each of the tribes was a son of Jacob, and collectively they were the “sons of Israel.”

While some of the blessings are brief, such as those upon Gad, Asher, and Naphtali (v. 19-21), others are significant. In reading the text of Genesis the turn taken by later Israelite history comes across as unexpected. This is one of the great pieces of evidence of the antiquity of the traditions here represented. While the narrative has certainly been shaped by later hands, it has not been accommodated to later history. The patriarchal narratives which begin in Genesis 12 follow a specific line of descent. The narrative follows the life of Abraham, then Isaac rather than Ishmael, and Jacob rather than Esau. The narrative then shifts, and roughly the last third of the book of Genesis then follows the life of Joseph. Joseph’s descendants, however, do not become a major focus of the Hebrew scriptures going forward, even in the remainder of the Torah. This is not because the Ephraimites, in particular, were not important to the later life of Israel. They were the largest and most numerous tribe in all of Israel and became the central and ruling tribe in the northern kingdom of Israel after the split with Judah. The northern kingdom is often referred to later in the Hebrew scriptures, in Psalms and prophecy, as Ephraim.

In Genesis 48, before his blessing on Joseph and his brothers, this was predicted in the scene in which Jacob blesses Joseph’s two oldest sons, Manassah and Ephraim. Though Ephraim is the younger, Jacob prophecies that he will be greater and more numerous (v. 13-17). It is worth noting that in giving this blessing, Jacob crossed his arms right over left. As a way of honoring Joseph, he adopts these two as his own sons to inherit alongside Joseph’s brothers (v. 5). It is for this reason that throughout the scriptures, even in the Revelation of St. John, Manassah and Ephraim are reckoned as tribes of Israel (Rev 7:6,8). Though his blessing on Joseph is effusive and positive (49:22-26), it comes to naught through the unbelief of Joseph’s descendants in parallel to the way in which the blessings of God were squandered by the northern kingdom of Israel, the kingdom which bore Jacob’s name.

Several of these “blessings” more resemble curses. As mentioned in last week’s post, this includes that spoken of the tribe of Dan, from which it was prophesied that a judge would come (v. 16), but that the tribe would be like the serpent (v. 17). Jacob’s vision of Dan’s future leads him to cry out to the Lord for salvation (v. 18). Likewise condemned, though he is the firstborn in order, is Reuben. Despite being the firstborn, Reuben had attempted what was known in the ancient world as family usurpation. He attempted to father a child with one of the wives of his father in order to make himself the head of the family (Gen 35:22). Because he was the firstborn, this act was especially treacherous. He was set to inherit as the heir anyway, and so it represents an attempt to sieze control of the family and its possessions from his father while his father was still alive. Other instances of this horrible crime were committed by Noah’s son Ham (Gen 9:21-23) and David’s son Absalom (2 Sam/2 Kgdms 16:21-22). Jacob curses Reuben for his crime and takes away his status as firstborn (Gen 49:3-4).

Symeon and Levi are likewise cursed, the second and third born sons respectively. Symeon and Levi had disobeyed their father in carrying out a massacre in Shechem through treachery to get revenge for what some of the men of the city had done to their sister Dinah (Gen 34). This jeopardized the whole family’s safety in the land, and so Jacob curses them with a lack of inheritance in that land (Gen 49:5-7). Through Moses and Aaron, Levi would come to hold the priesthood for Israel, but part of this priesthood was that they had no land inheritance of their own (Deut 10:9). Benjamin, somewhat surprisingly given his favored and special status in the patriarchal narrative as the second son of Rachel, is also spoken of in negative terms (v. 37). This statement is prophetic and likely related to the role of the Benjamites in the later Israelite civil war (Jdg 19:12-20:48) and Saul’s short-lived Benjamite monarchy which was seen as illegitimate.

The most important prophetic element of the Testament of Israel, however, is that concerning Judah (Gen 49:8-12). Judah was the firstborn son, and the disinheritance of Reuben, Simeon, and Levi made him the heir and granted him firstborn status. It is the line of Judah which will come to represent the believing, covenant line through the remainder of the history of the old covenant. It is therefore reasonable that the prophecy here describes the legitimate line of kings as coming from Judah (v. 8, 10, 11). This prophecy also shapes the hope given to Adam and Eve after the expulsion from Paradise, the seed of the woman (Gen 3: 15), into specifically Messianic promise. The word “Messiah” or in Greek “Christ” is a title for the anointed king. Judah’s kingship is prophesied to be immediate over the sons of Israel (Gen 49:8) but ultimately over all the nations and peoples of the world (v. 10). Judah becomes the focus of Biblical history because the purpose and goal of that history are to produce the seed of the woman, the seed of Abraham (Gen 22:18; Gal 3:16), the Christ.

The imagery used in the blessing of Judah by his father is further developed later in the scriptures as descriptors of the Messiah. The figure described with his purple garments is taken to be this singular individual, the Christ. The comparison of the Messiah to a lion, the lion of the tribe of Judah, led to the use of the lion as a symbol of the Davidic monarchy in Jerusalem throughout its history. St. John identifies Jesus as this lion in Revelation 5:5. The imagery of the king’s foal and donkey’s colt tied to a vine (Gen 49:11) is further developed by the prophet Zechariah (Zech 9:9-10). In what is clearly a Messianic prophecy, the Christ is described as coming to Jerusalem riding on these same animals. As narrated in all four Gospels, as Jesus makes his entry into Jerusalem, he quite literally fulfills these prophecies in detail (Matthew 21:1-11, Mark 11:1-11, Luke 19:28-44, and John 12:12-19). The animal which Christ rides is found tied to a plant. St. Matthew wishes this fulfillment to be so clear that he seems to imply that Christ rode two animals at the same time (Matt 21:7).

The final verse of Israel’s prophecy over Judah is later developed in Biblical imagery to refer to the death and resurrection of Christ. The Messiah’s eyes are said to be “dull” or “dark” from wine. Christ repeatedly describes his passion and death as drinking from a cup (eg. Matt 20:22-23; Mark 10:38-39; Luke 22:42). This depiction of dead eyes is, however, followed by a description of teeth white from milk, a description of new life as represented by a young infant. This more closely ties the figure of this prophecy to the figure prophesied against the devil in Genesis 3:15. Through the guile of the serpent, humanity has become subject to death. The defeat of the serpent comes after the seed of the woman has been struck by the power of death, and represents new, and ultimately eternal, life through readmission to the tree of life. As our Lord Jesus Christ rides into Jerusalem triumphantly on Palm Sunday, it represents both the fulfillment of prophecy, identiying him as the Messianic seed who was to come, and a prophecy itself. It is an assurance that he would soon be struck by death, but would emerge victorious on the other side, bringing new life to humankind.

Thanks Father for another great post; I’m always wanting more by the time I read to the end.

I had a question for you about Ham’s usurpation of Noah. Gen 9.21ff has always perplexed me as to what happened; when I was Presbyterian the commentaries I consulted weren’t of much help either. What did Ham do in this passage; it seems more occurred than stated?

There are several details in the story of Ham’s sin that are tip-offs as to what happened. Ham’s crime is uncovering his father’s nakedness. Leviticus 18:7-8 identify this as a euphemism for having sexual relations with the wife of one’s father. In the original Hebrew, Genesis 9 says that Ham came out of “her tent” though this was later corrected, and in most translations render it ‘his tent.’ In addition, though people commonly refer to a curse being put upon Ham, there is no curse put upon Ham in the text. Rather Noah curses, and disinherits, Canaan, Ham’s son. Canaan is the fourth and youngest son of Ham, Noah’s third and youngest son. The text itself here reminds the reader of this. There is no reason for Noah to disinherit his youngest son’s youngest son who would have, at any rate, inherited almost nothing. Unless, of course, Ham’s youngest son was also the son of Noah’s wife, Ham’s mother, and had been borne in an attempt by Ham to seize control of the household and the inheritance from his father. This is little discussed because it is quite ugly, but that is what happens in the latter portion of Genesis 9.

My jaw just dropped! Father…incredible! You know your stuff!

Christopher, thanks for asking. I had two questions in mind…that was one of them.

Thank you Father Stephen. In the cases of Absalom and Reuben, we’re told that they slept with their father’s concubines. In the story of Noah, it seems that Noah’s wife is also Ham’s mother, additionally St Peter twice mentions only eight were saved thru the Flood (1 Pt 3.20 & 2 Pt 2.5). Is this a correct reading? Also is there any connection with the passage of the conception of Ammon and Moab by Lot’s daughters with Lot (Gn 19.30 ff)?

Thank you Father. Very good, as always.

Never did make that connection between Jacob’s prophesy to Levi about his loss of land inheritance and the non-landownership of the Levites. That was good, Father. I just assumed it was for priestly “spiritual” reasons.

Would you explain the last part of Gen 49:10 “until Shiloh comes”? … specifically, on the name Shiloh. As a Messianic prophesy, some say Shiloh is Jesus, yet the name Shiloh is in other parts of the OT, that it was the place where the Ark of the Covenant dwelt for 400 years (?). Please tie the loose ends for me!

Genesis 49:10 is an interesting case. The Greek, Vulgate, Syriac, and the Aramaic Targums all read ‘until it comes to the one for whom it is intended’ or similar. It is only the Hebrew that has ‘until Shiloh comes’ or ‘until it comes to Shiloh’. The former reading from the ancient versions makes this part of a clearly Messianic prophecy. The Hebrew reading seems to blunt that and make it a historical reference to David bringing up from Shiloh. The Fathers all understand it as a Messianic prophecy, though they are reading from those ancient versions. Some folks prone to slamming the Hebrew might argue that it was deliberately changed to get rid of the Messianic prophecy. I think it more likely that the Hebrew here just contains a very slight error. If the consonants here were, “sh l ch” instead of “sh l h,” a tiny difference in the last Hebrew letter in the Hebrew alphabet, then it would read, “until it comes to the one who is sent” and would generally match up with the interpretations of the other ancient versions. I think that that is the most likely scenario.

Very helpful explanation Father. That “tiny difference” is quite significant. “Until it comes to the one who is sent” fits smoothly into the entire blessing Jacob gave to Judah, as a Messianic prophesy. Can’t say the same for “Shiloh”.

Thank you. Appreciate it.