In understanding the portrait of the Messiah presented in the Hebrew Scriptures as understood in the first century, the time of the apostles, Psalm 110/109 looms large. This Psalm is, in fact, the most cited Old Testament text in the New Testament. It encapsulates themes and images found predominately in the Torah and developed within the prophets to give a picture of the Christ, the Anointed One, who will come into the world and what it is which he will accomplish. The core thesis of Christianity, and of all of the New Testament documents, is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ, the Holy One of God. It, therefore, makes perfect sense that applying the imagery of this Psalm to the life and person of Jesus is a primary focus of the New Testament authors.

In understanding the portrait of the Messiah presented in the Hebrew Scriptures as understood in the first century, the time of the apostles, Psalm 110/109 looms large. This Psalm is, in fact, the most cited Old Testament text in the New Testament. It encapsulates themes and images found predominately in the Torah and developed within the prophets to give a picture of the Christ, the Anointed One, who will come into the world and what it is which he will accomplish. The core thesis of Christianity, and of all of the New Testament documents, is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ, the Holy One of God. It, therefore, makes perfect sense that applying the imagery of this Psalm to the life and person of Jesus is a primary focus of the New Testament authors.

In addition to the coalescence of various themes regarding the coming Messianic seed, this Psalm incorporates the figure of Melchizedek from Genesis 14:18-20. The brief mention of this figure in the Torah is ambiguous and even mysterious. He is introduced in Psalm 110/109, however, in a context that clearly expects to make an important point regarding the character of the coming Christ. These two are the only explicit mentions of Melchizedek in the Hebrew Scriptures. There is, in fact, much more said about Melchizedek in the Epistle to the Hebrews in the New Testament, reflecting the importance of the figure in Second Temple worship and piety, than there is in the Torah or this Psalm. How, then, does Melchizedek enter into this Messianic picture and what is his significance such that much of that picture would ultimately come to focus on him?

Psalm 110/109 is most often cited in Scripture through the quoting of its first verse. This is, of course, because the Psalms were not organized and numbered in the familiar way at the time of writing of the New Testament texts. It begins, “Yahweh said to my lord, ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool'” (v. 1). This Psalm was from an early period attributed to David, meaning that the reference here is not merely to the human king of Judah, as the second figure here is that king’s lord. Likewise, it cannot be the title ‘lord’, in Hebrew ‘adoni‘, applied to God, as Yahweh is here differentiated from this ‘lord’. This is a second person, who is the lord or master of even the king, and who sits, and therefore rules, at the right hand of Yahweh. In the ancient world, one did not sit in the presence of one’s superiors. To do so was a sign of disrespect. Therefore Yahweh inviting this person to sit at his right hand is not only honoring him with the most important position in Yahweh’s council but is acknowledging equality.

Also contained within this first verse is a description of a period of time during which the Messiah, following his enthronement, will, as the second verse reiterates, rule in the midst of his enemies. This means that there is, between the enthronement and beginning of the rule of the Christ and the final judgment described later in the Psalm a Messianic age, a Christian age if one will, made up of a certain period of years of the Lord. Here the Messiah’s kingdom is represented by a scepter that goes forth from Zion, from Jerusalem. This again identifies the Christ figure, already identified as a divine being, as a human of David’s line, of the Judahite monarchy. This also picks up the Messianic thread from the Torah regarding the seed of the woman, the seed of Abraham, descended from the tribe of Judah (Gen 49:10).

Later in the Torah, in the fourth and final oracle of Balaam son of Beor whose eye was opened by Yahweh, this scepter was associated with judgment: “I see him but not now. I behold him but he is not near. A star will come out of Jacob and a scepter will arise from Israel. It will crush the skull of Moab and smash all the sons of Sheth” (Num 24:17). This oracular vision culminates in condemnation of the giant clan of Amalek, the prototypical demonic enemy of Yahweh (v. 20) and the descendants of Cain (v. 21-22) in a play on the name of the Midianite tribal group.

Likewise, the fifth and sixth verses of Psalm 110/109 describe the final victory of the Messiah over his enemies. It is worth noting that the ‘Lord’ referred to in verse 5 is the Christ himself at the right hand of Yahweh. Here, the Lord defeats the enemies while in verse 1, it is Yahweh who defeats them, describing the unity of both divine persons. The language here parallels that of Balaam’s oracle, describing the shattering of kings, judgment among the nations, and the shattering of chiefs all across the earth (v. 5-6). These kings and chiefs, here as in Numbers where this violence is directed toward Amalek and those descended from Cain, are the demonic rulers, the rebellious spiritual powers. With their defeat, Yahweh the God of Israel and the Lord, the Christ, will rule the entire earth with their enemies destroyed. This is not an allegorical interpretation of “real-world” violence, but the original intent of the Psalmist and poet.

Those who oppose the Messiah during this period, the Messianic or Christian age, are not his people, though that was the case before his enthronement. Rather, it is his people who are liberated by the judgment of the spiritual forces of evil who are their enemies as well. His people, in fact, stand upon the holy mountains, redeemed and in the presence of God (v. 3). The Messiah’s divine nature is also, in this same verse, reiterated by identifying the dew of his youth with the womb of the morning, before the creation of the world.

This portrait frames the mention of Melchizedek in the fourth verse. “Yahweh has taken an oath and will not relent, ‘You are a priest unto eternity according to the way of Melchizedek.'” It is immediately plain that this is signifying, minimally, that the Messiah will be both a king, as already described, and a priest. This means that in the figure of the Messiah, rule and priesthood, separated in Israel and Judah since the time of Moses and Aaron, would be brought back together. However, the priesthood of the Messiah is not here described in terms of the Aaronic priesthood but another, that of the figure of Melchizedek from Genesis.

The account of Genesis represents the only direct information about Melchizedek and his priesthood which precedes the composition of this Psalm and to which the Psalm can clearly be taken to be referring. Melchizedek appears abruptly to Abram after the latter’s victory over Chedorlaomer and the other kings who had taken his kinsman Lot captive. He is identified by his name, Melchizedek, and as the king of Salem. The name, Melchizedek, is a Canaanite theophoric. This means that it contains the name of a god, in this case, a Canaanite one, ‘Tzedek’. His name literally means ‘my king is Tzedek’. It appears from other Canaanite textual evidence that Tzedek worship was a subset of the worship of the sun god Shemesh in Canaan. This worship seems to have been centered in the area surrounding Jerusalem for some time, as at the time of Joshua’s conquest, the king of Jerusalem is named “Adonizedek” or “my lord is Tzedek” (Josh 10:1-3).

As just stated, Melchizedek is the king of Salem, which is the city of Jerusalem. The city’s name also includes the name of a Canaanite god, Shalim. The earliest known mention of the city in Ancient Near Eastern sources names the city as ‘Uru-shalim‘ in Akkadian. ‘Uru‘ is the Sumerian loan-word for ‘city’, so this would refer to the ‘city of Shalim’. In later northwest Semitic dialects, the derived word ‘yeru‘ was used for an establishment or foundation. This, then, is the origin of the more well-known name of the city. Melchizedek, therefore, has the name of one pagan god in his name and another branded upon the city which he rules.

It is because of these clear pagan identifiers that the Torah clarifies that Melchizedek, despite these pagan origins, is the priest not of Tzedek or of Shalim, but of the Most High God (Gen 14:18). From the perspective of the Torah, Tzedek and Shalim are not fictional characters but are lesser angelic beings created by Yahweh to whom he assigned the governing of the nations at the Tower of Babel event (Deut 32:8). Their worship was strictly forbidden and though Melchizedek is king of a pagan city and was named for a pagan god, just as Abram came from Ur, he is a priest and worshipper of the Most High God, not these lesser powers. Abram himself clarifies this when he identifies Yahweh explicitly as the Most High God whom he worships with Melchizedek (Gen 14:22). The bread and wine which Melchizedek brings forth as a priest are clearly within the context of sacrificial offering in which Abram participates through eating. He thus mediates the blessing of Yahweh to Abraham (v. 19-20). Abram tithes to Melchizedek, thereby acknowledging him as representative of God to him on earth (v. 20).

What, then, is the manner or way or order of Melchizedek’s priesthood? What distinguishes it from the priesthood of Aaron? Aaron’s priesthood, the high priesthood of Israel and then Judah, served an iconic function parallel to that of the monarchy. The clear connections between the high priestly vestments and the vestments with which idols were clothed within pagan temples make clear that the high priest was to be an icon of the God of Israel. This same connection is brought over into the episcopal vestments of the Orthodox Church which form a part of the bishop serving as the icon of Christ. Likewise, the king served as an icon of Yahweh, the God of Israel’s rule in establishing justice. While it is true that king and priest are reunited in the Messiah and that Melchizedek was both king and priest, Melchizedek’s mode of the priesthood is also qualitatively different than even the combination of these two iconic or imaging functions.

Melchizedek, living at the beginning of the second millennium BC was not a holder of two separate offices, priest and king. He was, rather, a priest-king. As was common throughout the ancient world up to and including the Roman Emperor, the ruler was also seen as the high priest of the religious rites. He was able to fulfill this function because he was seen to be himself divine. As a divine being, one of the gods, he was a member of the divine council of the gods, the pantheon, and could, therefore, mediate within his person between the gods in their deliberations and the human world. Priest-kings were both the leaders of worship and the recipients of worship. They governed their cities as the other gods governed other realms. They were seen to have a relationship with the god of the city as divine father or mother and son. This was seen by ancient Israelites and Judeans of the Second Temple period as real, though in actuality the fellowship of these rulers with demons. Rulers even to a very late period from among the pagan nations were equated with the giants of old as demonic/human beings.

The only holder of this office who is, nevertheless, considered by the Torah to be serving Yahweh rather than entering into relationships with these demonic beings is Melchizedek. Describing the Messiah as holding this office of priest-king, then, has certain immediate and startling implications. It places further emphasis, already present in Psalm 110/109, on the Messiah as a divine being in general, and the second person of Yahweh the God of Israel in particular. The latter is required by the fact that the Christ here is seen to be a recipient of worship in addition to an offerer within the commandment that only Yahweh may be a recipient of any kind of worship. The Christ is not an icon of Yahweh’s rule in his kingdom. He is Yahweh ruling over his kingdom. The Messiah is not an icon of Yahweh leading the worship of the people and interceding for them, but is Yahweh himself, allowing him to sacrificially function as the offerer, the offered, and the recipient of the sacrifice. The Epistle to the Hebrews understands Christ’s high priesthood in light of the figure of Melchizedek in precisely these terms.

And Hebrews is not alone in the Second Temple period. In fact, Melchizedek became a name for the expected Messiah just as ‘David’ or ‘the Son of David’ did. For example, among the Dead Sea Scrolls is a text known as 11Q13 or 11QMelchizedek. Though fragmentary, it gives a window into the understanding of the view of Melchizedek as Messiah during the centuries preceding the birth of Jesus Christ. “Melchizedek will return them to what is rightfully theirs. He will proclaim to them the Jubilee, thereby releasing them from the debt of all their sins” (5). “Then the Day of Atonement shall follow after the tenth jubilee period when he shall atone for all the Sons of Light and the people who are foreordained to Melchizedek…for this is the time decreed for the year of Melchizedek’s favor” (5-9). Note that in the final phrase from Is 61:2, Melchizedek’s name replaces that of Yahweh. “By his might, he will judge God’s holy ones and so establish a righteous kingdom, as it is written about him in the Psalms of David, “God has taken his place in the council of God. In the midst of the gods, he holds judgment” (9-10). Here Melchizedek establishes his kingdom by enacting the judgment of the gods of the nations as described in Psalm 82. This interpretation continues, “How long will you judge unjustly and show partiality to the wicked?” citing verse 2 of that Psalm. The text goes on to make clear that this judgment is against the demonic gods of the nations, who are the enemy kings and chiefs destroyed in Psalm 110/109. “The interpretation applies to Belial and the spirits foreordained to him because all of them have rebelled, turning from God’s statutes and so becoming utterly wicked. Therefore Melchizedek will thoroughly prosecute the vengeance required by God’s statutes. Also, he will deliver all the captives from the power of Belial and from the power of all these spirits. Allied with him will be all of the righteous gods” (12-14).

After a lacuna, the text picks up describing the coming of Melchizedek in terms of the gospel described in Isaiah. “This visitation is the day of salvation that he has decreed through Isaiah the prophet concerning all the captives as it is written, “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of the messenger who announces peace, who brings the gospel, who announces salvation, who says to Zion, ‘Your God reigns'” (15-16). The quotation of Isaiah 52:7 associates as was normal in the ancient world the gospel proclamation with a victory which leads to the enthronement of God to reign over the earth. It is further interpreted, “The messenger is the anointed one [Messiah] with the Spirit of whom Daniel spoke, ‘After the sixty-two weeks, the Messiah will be cut off’…Your God is Melchizedek, who will deliver them from the power of Belial…then you shall have the trumpet sounded” (18-25). Here the Melchizedek figure is identified as the Messiah. He will be cut off but will return and be enthroned. He is further identified as God himself. After his final defeat of Belial and the spirits of wickedness, the final trumpet will sound and his final reign, over the righteous saints, will be fulfilled.

The testimony of all the apostles, as witnessed by all of the New Testament documents, is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ, the Holy One of God. Throughout these texts, they described how Jesus fulfilled the portrait of the Messiah from the Old Testament, including especially the image of the priest-king Melchizedek. They understood that Jesus Christ is God, that he is Yahweh himself, the second person or Yahweh, and also man descended from Abraham and David according to the flesh. In Christ’s crucifixion, death, and resurrection the apostles understood the victory which he had won over the powers of death, sin, and corruption. They understood the cross as the eschatological day of atonement, freeing the people from their sins. They understood Christ’s ascension into heaven as his enthronement to rule for an age in the midst of his enemies until those enemies’ final defeat at the sounding of the last trumpet. They took the report of this victory, this gospel, to all the nations, to the ends of the earth.

In view of your comments above about the vestments of Aaron and those of an Orthodox bishop, you might be interested in the article by Basil (Osborne), Bishop of Sergievo, “The Making of a Priest in the Byzantine Tradition”, second item on the page at https://jbburnett.com/theology/theol-ltg-ot-roots.html.

Fr Stephen,

What wonderful insight. Thank you for this ministry. Question: Is Melchizedek’s appearance in the Book of Genesis the same as the appearances of the Second Hyposatsis of YHWH in the OT, i.e. The Angel of the LORD, GOD the Word and The Son of Man instances or is he an actual human person? Do the Fathers speak to this at all? Thanks

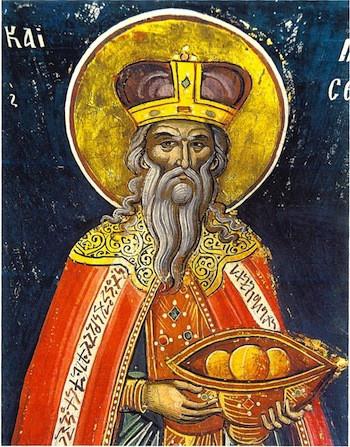

It’s tempting to move in that direction, but I think its ultimately a misinterpretation of the data. There are places where that connection is made here and there. Philo, for example, in a couple places indicates that Melchizedek was a historical person, but in one place says that he is the Logos. But the general understanding in Second Temple sources is that Melchizedek was a historical person and that he is in various ways indicative of the coming one. In much the same way that the Melchizedek scroll I cited speaks of the coming Messiah, the second person of Yahweh, as ‘Melchizedek’, other texts refer to him as simply ‘David’. The latter aren’t implying that David was not a historical human or that the Messiah would be David himself reincarnated or descended from heaven. See also St. Elias vis a vis St. John the Forerunner. So we talk about the Spirit and power of Elijah and the Order of Melchizedek. In Orthodox tradition, the icon that heads this piece, for example, indicates an understanding of Melchizedek as a historical person and saint, as does the practice of especially monastics taking his name as one of the OT prophets.

A very enlightening writing. Question: about ” Christ’s ascension into heaven as his enthronement to rule for an age in the midst of his enemies until those enemies’ final defeat at the sounding of the last trumpet. ” Is this age referred to as the millennial reign in the Apocalypse of St. John? Thanks.

Short answer: Yes.

Really appreciate your input Rev Stephen to the Remnant Radio podcast and absolutely loved this post on Melchizedek. I just had a conversation with someone the other day who did not understand this and your entry here will be a great tool for passing on. Blessings to your ministry!

So if Christ is a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek then I take it that Christian priesthood under Christ would also be according to Melchizedek rather than on the Jewish Aaronic priesthood?

Yes. The Aaronic priesthood was the result of the separation of king and priest following Moses. Those are reunited in Christ and so the royal priesthood supersedes the Aaronic.

Thank you, Fr. Stephen. I’d like to ask one more question about the Mechizedekian priesthood.

That Jesus is the High Priest according to the order of Melchizedek seems to imply there are priests under Him.

Would it be accurate to say believers participate in that priesthood in two modes? One being the priesthood of all believers and the other the ministerial sacerdotal priesthood of the clergy?

By Baptism/ Chrismation, we are all Melchizedekian priests under the High Priest and some are priests in a more full way of participation?

There are two major shifts in the priesthood described in the Torah. The first is that priesthood is taken away from Moses and given to Aaron following Moses’ sin in not circumcising his son. This leads to the separation of judge/king and priest that pertains until they are reunited in Christ. The second shift happens after the worship of the golden calf. We tend to skim over this, but the Levites were not the priests of Israel until after that episode which describes how, by standing with Moses in judging the perpetrators, the priesthood was given to them. Aaron and his sons had already been appointed as the high priestly line to serve in the tabernacle. But other sacrifices and offerings (i.e. the Passover) were being performed by the heads of households and clans and tribes, the elders (presbyters) of the people. When they instigated Aaron to the sin with the calf, they had the priesthood (and their lives) taken from them and the priesthood was given to the Levites. So the restoration of the priesthood of Melchizedek, in which priest and king are combined, also involves the restoration of the priesthood to the people of God as a whole as represented by their elders (presbyters). This is why in Orthodox liturgical understanding, the priest leads and represents the people in various capacities in the administration of the mysteries. The Church as a whole serves as priests for the creation, led by her presbyters. The episcopal office includes this priesthood but also includes a form of the high priesthood. Aaron as high priest, bearing the name ‘Yahweh’ on his diadem and dressed as the ancients dressed the idols in their temples, serves as an icon of the God of Israel in the midst of the people. What qualifies Christ as the Great High Priest is that he is the express image of the Father and so fulfills (filling to overflowing) that role. The bishop, then, is a priest and leader of the people but also serves as an icon of Christ in exercising his authority within the Church.