Recent posts have discussed the divine council of angelic beings which surround the throne of God, the way in which certain individuals in the Old Testament were exalted to join that council, and the way the saints in Christ become members of the divine council, sharing by grace in Christ’s rule over his whole creation. Within these themes, and the mediatory role of the saints and their patronage, the Theotokos, Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, has a special role, as has been recognized within the Christian faith from the very beginning. The veneration of the Theotokos in the West developed in ways which ultimately produced Marian dogmas which the Orthodox Church does not recognize. In response to these developments, the heirs of the Protestant Reformers, though not those Reformers themselves, reacted by seeking to minimize the importance of the Theotokos, to the point of rejecting details of her personal history and life which had been held universally since our earliest sources. Once the role of the Theotokos within the divine economy had been repudiated, Protestant scholars had the need to explain how these teaching came into being, and came to be universally held. It has become common for those scholars to suggest some connection between the veneration of St. Mary and pagan goddess worship, related to their suggestion that the veneration of the saints in general contained some connection to polytheism. As was seen in the case of the role of the saints, however, it will be seen that the veneration of the Theotokos as experienced within the church has existed from the beginnings of the faith, being grounded firmly in the scriptures and in the religion of Second Temple Judaism and its anticipation regarding the mother of the Messiah.

Recent posts have discussed the divine council of angelic beings which surround the throne of God, the way in which certain individuals in the Old Testament were exalted to join that council, and the way the saints in Christ become members of the divine council, sharing by grace in Christ’s rule over his whole creation. Within these themes, and the mediatory role of the saints and their patronage, the Theotokos, Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, has a special role, as has been recognized within the Christian faith from the very beginning. The veneration of the Theotokos in the West developed in ways which ultimately produced Marian dogmas which the Orthodox Church does not recognize. In response to these developments, the heirs of the Protestant Reformers, though not those Reformers themselves, reacted by seeking to minimize the importance of the Theotokos, to the point of rejecting details of her personal history and life which had been held universally since our earliest sources. Once the role of the Theotokos within the divine economy had been repudiated, Protestant scholars had the need to explain how these teaching came into being, and came to be universally held. It has become common for those scholars to suggest some connection between the veneration of St. Mary and pagan goddess worship, related to their suggestion that the veneration of the saints in general contained some connection to polytheism. As was seen in the case of the role of the saints, however, it will be seen that the veneration of the Theotokos as experienced within the church has existed from the beginnings of the faith, being grounded firmly in the scriptures and in the religion of Second Temple Judaism and its anticipation regarding the mother of the Messiah.

The earthly authorities of the old covenant were a direct reflection of the divine council, through which the God of Israel exercised his rulership and authority over his creation. The earliest institution of the Torah were the 70 elders surrounding the one appointed to judge Israel, 70 in number because that was the number of the divine council assigned to govern the nations (Deut 32:8). This remained when there came to be a divinely-appointed king. The earliest kings, Saul and David, as they made war to secure the land given them by God, were surrounded by their mighty men (gebur’im) who led their armies, in parallel to the heavenly hosts surrounding YHWH Sabaoth. The Archangel Gabriel’s name identifies him as the ‘Gebur’ or mighty man of God. With the kingdom established under David, this took the form of the elders of the people and the royal court surrounding David as he ruled and administered that kingdom. In all of these cases, the earthly authority served as an image of God’s heavenly authority, and was commanded to serve in the administration of God’s authority. Kings are then judged based on how well they image the righteous rule of God on earth in their role. The king and his royal council was not only an image and earthly reflection of God’s heavenly rule, but was also a prophecy of a day when earthly and heavenly rule would be united as one in the Messiah.

Within the southern kingdom of Judah, which was ruled by the line and house of David from the division of the kingdoms until the exile in Babylon, an important institution grew up within the king’s court. It is this Davidic line which 1 and 2 Chronicles go to great pains to emphasize continues after the destruction of Judah, such that it will one day produces the Messianic king. This is why we are reminded in the genealogies of St. Matthew and St. Luke, and the accounts of Jesus’ birth that he is of this line according to the flesh. Typically, when we consider the king and queen of a nation, based on medieval Europe we assume that the queen of a nation is the wife of the king. This, however, is because that medieval paradigm had been deeply effected by Christianity such that it had to at least make pretense to monogamy. In the ancient world, as we see reflected in 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles polygamy was widely practiced by the wealthy, which of course included kings. This was never a way of life sanctioned by God, in fact, the Torah explicitly forbids kings from practicing polygamy (Deut 17:17). It was, however, the reality. For this reason, rather than the office of queen belonging to a first or favored wife, it belonged to the mother of the king. Kings might have many wives, but could have only one mother. The reality of polygamy, however, does not fully explain the institution of queen mother within Judah because there is no parallel institution in the northern kingdom of Israel, let alone in many other monarchies of the ancient world which were equally polygamous. It is unique to David’s line within Judah.

The origination of this institution is describes in 1 Kings 2:19, as Solomon shortly after his succession to the throne has a second throne brought out and placed on his right hand for his mother, Bathsheba, to sit beside him as queen. The significance of being at the right hand of the king is clear throughout the scriptures, preeminently in Christ’s own enthronement being described as being at the right hand of the Father. This is the preeminent position within the king’s council, and establishes her as his foremost advisor. From this point on, throughout 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles, as the succession of each descendant of David to the throne is announced, his mother is named because she holds this role (See 1 Kgs 14:21, 15:2, 15:10, 22:42, 2 Kgs 8:26, 12:1, 14:2, 15:2, 15:13, 15:30, 15:33, 18:2, 21:1, 21:19, 22:1, 23:31, 23:36, 24:8, 24:18 and parallel passages in 1 and 2 Chronicles). In a particularly dark period of Judah’s history, Athaliah used the authority of this role as queen mother to attempt to wipe out the Davidic line (2 Kgs 8:26, 11:1-20). This institution is referred to elsewhere in the Old Testament, a chief example being Psalm 45. This Psalm is an ode to the king, and as the king is the icon of the God of Israel, it moves easily from praise of the king himself (v. 2) to praise of God (v. 6), with the lines sometimes blurring between the two. This, too, is prophetic of the Messianic king who will someday unite the two. Within the imagery of this ode to divine kingship is the statement that at the king’s right is the queen in glorious array (v. 9). This Psalm concludes with a prophecy of the future role of the saints in governing the nations (v. 16).

The most basic claim of the entire New Testament is that Jesus is the Christ, the Messiah. Because Christ is also proclaimed to be the incarnate second hypostasis of the Holy Trinity, in him heaven and earth, the divine and the human, are united. This includes, at his enthronement at the ascension, the union of the throne of God and the throne of David, already, as we have seen, prophetically linked in their institution. The reign of Jesus Christ over his kingdom is not only the bringing together of Davidic and divine rule, but is the fulfillment of the former. The words of Psalm 2:7, “Today you are my son, today I have begotten you” are a critical part of this royal psalm, read at the succession to the throne of a new Davidic king. Within the idea of adopted sonship is the idea that the son now has the obligation to serve as an image of the Father. This is fulfilled in Jesus Christ, who is the express image of God the Father (Heb 1:3). But it is also fulfilled at the baptism of Christ, in which Christ is anointed at the hand of the prophet, not with oil but with the Holy Spirit, and the words of succession are spoken (Luke 3:22, Acts 13:33, Heb 5:5). Christ is the true Son of God, begotten, not adopted.

For a faithful believer in the God of Israel in the first century AD, religious expectation was focused in the coming of the Messiah, and the beginning of the Messianic age. It would, therefore, have been natural when such a person heard the apostolic proclamation that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ who has come, to ask the name of his mother. It would have been a natural expectation, based in the scriptures and traditions of the Jewish people, to expect that his mother would have this role, at his right hand, as closest advisor and queen. The New Testament authors take great pains to correct popular misunderstandings related to the Messiah, particularly the idea that he would be a political leader in this world, and would come to establish an Israel in this world free from Roman domination. At no point, however, do these authors seek to correct this expectation as it pertains to Christ’s mother. Repeatedly, throughout the scriptures of the New Testament, these expectations are reinforced through the importance of the Theotokos not only in the ministry of Christ, but in the early community of the church as described in the opening chapters of the Acts of the Apostles. As just one example, there is a clear parallel between the interaction between Bathsheba and Solomon in 1 Kings 2, and that between the Theotokos and Christ at the wedding at Cana (John 2), though the Theotokos shows herself a wiser and more holy woman than her ancient ancestor.

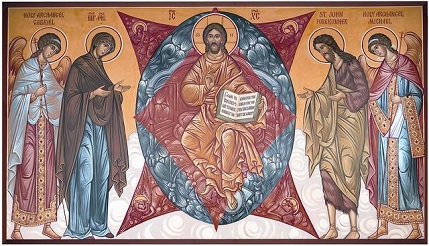

It is this understanding which has led, since the beginning of the Christian faith, to the special role given to the Theotokos among the saints in glory. It is she who stands at the right hand of Christ the king, and among the intercessors with whom Christ shares his rule and reign, she has a special status of honor. She stands as the fulfillment not only of queen motherhood, but of motherhood itself (Gen 3:15), and even, we may see, of womanhood.

Fr. Stephen:

thank you for a wonderful article. I learned much within it.

But I feel i must humbly disagree with you on this assertion: “the Torah explicitly forbids kings from practicing polygamy” in Deut 17:17. Especially with your choice of “explicitly”. The verse before this forbids kings “multiplying” horses to themselves. And verse 17 itself does the same for “silver and gold”. The word multiply must mean exactly that: multiplication, not addition. For surely, a king must have more than one horse or one piece of silver or gold! The prohibition was for the king not to amass so much military or financial power that the king forgets that his true security comes from God. And to not marry wives by the hundreds or thousands, as conquerors then did, whereby individual wives would be deprived of consort and affection by a husband overwhelmed by numbers. But the king was to marry them one by one, based on love or progeny or alliances, as befits a king.

Indeed, in 2 Samuel 12:8 Nathan quotes God as claiming to have given David “his master’s wives… and would have given you much more.” God gave David his wives, plural. How does that jive with a ‘prohibition’ of polygamy?

So, first, you make a valid point that ‘explicitly’ is probably too strong a word. I would argue that the Old Testament’s condemnation of polygamy is clear, but it is fair to argue that it is implicit. “Thou shalt not have more than one wife” would be an explicit condemnation of polygamy, and that phrase certainly does not occur. Nevertheless, Christ is able, in Matthew 19:4-5, to describe marriage between one man and one woman as God’s plan from the beginning. Correct me if I misread your comment, but you seem to be arguing that polygamy was not sinful within a certain (reasonable) number of wives. I have several problems with that argument. First, at no point in the Torah, or anywhere else in the Old Testament, is that number given. If beyond a certain number of wives it becomes sinful, then that number should be made clear somewhere, and it isn’t, even in the Mishnah and other later Rabbinic literature. This is relevant because Jewish communities practiced polygamy until the 11th century. Monogamy is grounded in a particular Christian reading of the Old Testament. But even in these Jewish communities, there does not seem to have been an express limit where it becomes sin.

Also, while the distinction you make between multiplication and addition makes sense in English, the Hebrew and Greek words used in Deut 17:17 don’t allow it. The Hebrew ‘ravav’ generally means ‘to increase’ or ‘grow numerous’ or ‘abound’. Likewise the Greek ‘plethyno’ means ‘to increase’ or ‘grow numerous’. Its the Greek word used for example of the growth of the church in the book of Acts following Pentecost. The two clauses of Deut 17:17 are parallel, in that having many wives was also a display of great wealth. Without here getting into the view of wealth in Deuteronomy, suffice it to say that the king is here not to be wealthiest man in the kingdom. The multiplication of wives for the king also brings with it the problem of marriages made to form alliances, meaning marrying non-Hebrews and worshippers of other gods. Jezebel entered the kingdom of Israel through such a marriage. Most importantly, we need to see the connections between what is said here in Deuteronomy, and the negative example of Solomon, who fails in particularly this area, and the positive example, of course, of Jesus Christ who is the only king of Israel to fulfill this passage, in having only one bride, and living a life of humble poverty.

Finally, in regard to 2 Sam 12:8, I think you’re reading that a bit against the grain if you think its purpose is to say that God is pleased with David’s polygamy. Quite the opposite. The reference here to Saul’s wives is serving a different purpose. First, there is no record of David actually having for a wife any of Saul’s wives. A few people have argued that Ahinoam, David’s second wife, was Saul’s wife Ahinoam, but there are several problems with that thesis. Chief among them is that Saul’s wife Ahinoam was the mother of David’s first wife, Michal, and so David marrying her second would have been both adultery, as Saul was still alive at the time, and incest. Nathan’s reference, in the context of him issuing God’s condemnation of David, seem to be rather a sarcastic reference to the fact that David had inherited Saul’s harem, his concubines, and so had plenty of women with whom to gratify himself sexually, so he had no excuse for taking Bathsheba, who belonged to another. Certainly no one could argue that Christ approves of wealthy men having harems of sexual slaves. David’s polygamous household degenerated into a nightmare of rape, incest, and murder by the end of 2 Samuel, so I find it hard to argue that that household was a gift of God, or a favored situation.

I agree that I expressed my case on that point too strongly, or at least in too cut and dried a manner, but I think the point I was attempting to make, that the reality of the institution of the queen mother in Judah does not validate polygamy, is correct.

Thank you Father Stephen!

This particular post is very special to me. Upon entering Orthodoxy I began to quickly understand the error I had been in for too many years regarding the special place the Theotokos holds in God’s salvation for mankind. Along with honoring Her, I long to know and love Her like I do Her Son., but as the heart needs refining, this takes time. Slowly, beginning by simple obedience I began to venerate and pray to Her and slowly beginning to have a sense of knowing Her. She is truly beautiful and gentle with this.

I was intrigued, as you walk us through this teaching about the history of the place of the Queen and Mother. I must say, arriving at the part where you describe the practice of polygamy and said “rather than the office of queen belonging to a first or favored wife, it belonged to the mother of the king” was a complete turning point for me…along with the fact that of all the ancient kingdoms this practice was only performed in Judah, “unique to David’s line within Judah”. I paused for a long while, in amazement.

Then the final walk through the article. I wondered how the Queen of Heaven fits into the Divine Counsel, since in the OT there is no mention of any particular woman there. It was where you said “…in [Christ] heaven and earth, the divine and the human, are united. This includes, at his enthronement at the ascension, the union of the throne of God and the throne of David…bringing together of Davidic and divine rule…” that answered my question. It is the fulfillment of prophesy in Christ, uniting the human and the divine. It is the New Covenant.

All the points you bring out throughout the entire article are gems. But those two for me helped tremendously. I could not help but exclaim ‘Oh the wonder…the wisdom and Providence of God’ ! It is truly amazing.

I wish I could express the extent of my appreciation for this post…and all the others, Father. All I can say is thank you so very much.

This is the kind of explanation that will lead serious Protestants to take Mary seriously. I found the logic of Divine Council and Mary on my own and it was the only satisfactory explanation I could accept. Once theosis, which leads to participation in the Council, replaces Original Sin and the resulting systems that result from it, Mary takes her place. I hope this may become standard Orthodox apologetics someday.

I expect it will where Orthodoxy is interacting with rationalist Protestants. And as more Orthodox converts from rationalist Protestantism have experiences to share.

It may not be so much of a rationalistic problem, but that the rationale Protestants have been exposed to comes from Roman Catholicism – which does not present a coherent reason to view Mary with such esteem. To a Protestant who follows Augustine much more consistently with Original Sin, Mary is just like any human being – all part of a damned mass of humanity (even if there is a higher opinion of her because of her, sort of election to her position). It is really a problem that originates with Original Sin. Christianity may not be rationalistic, but it should at least be internally consistent. This you won’t have when one the one hand you affirm everyone is depraved and torture deserving from birth, bound by their will to sin – but that somehow Mary and the Saints are the exception to this. You can’t deny free will and at the same time esteem someone for the acts of their will.

I know. I was a reformed Presbyterian of the most rigid sort. I do think that original sin is a big problem, as is the nature of Christ and the church. They are really only living on borrowed truth, and the more logical they get, the more truths they have to deny. At least, that was how I saw it 🙁

It does not seem that Orthodoxy has any sort of corner on Divine Council theology concerning Mary. In fact, both Orthodoxy and Catholicism largely do not use (or affirm) a hard-line Divine Council argument for much of anything. Hence why this article is such a breath of fresh air!

Both lungs of the Church would do well to integrate more Scripture—not only the Gebirah argument (which Catholics often use) but also the Divine Council passages—when they seek to defend the traditional view of Mary.

Thank you very much for all. Those posts are terrific. Very enlightening and helpful.

Because I’m not an orthodox, I respect and admire the Theotokos but can’t help but thinking of 1Tim 2:5 when talking of our relation with the saints and the Theotokos.

Once again thank you for the posts.