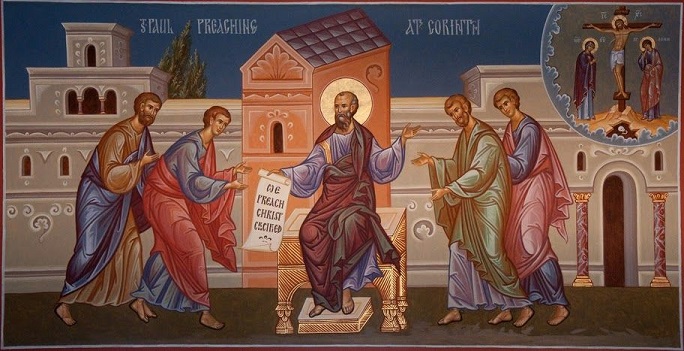

In chapter 8 of his First Epistle to the Corinthians, St. Paul begins a discussion that will go on for several chapters regarding food offered to idols. The eating of this food was the means by which worshippers participated in the sacrifices offered to those pagan gods. Through these chapters, St. Paul gives a variety of reasons why all of the members of the Christian community at Corinth must abide by the commandments against such participation as re-affirmed at the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15. In the opening chapter of this discussion, chapter 8, St. Paul makes a distinction between stronger and weaker brethren. This distinction understood rather casually, is employed all too frequently in both popular and pastoral discussions and debates in a way that belies the actual use to which St. Paul puts it. All too often, this distinction is used in order to create a sort of tyranny of the minority within communities or to justify judgmentalism of one group against another. In some cases, these misuses of St. Paul’s argument even involve a person identifying himself as the “weaker brother.” The point which the apostle is here making, however, is important. It is far too important to be lost to misuse and misapplication.

In chapter 8 of his First Epistle to the Corinthians, St. Paul begins a discussion that will go on for several chapters regarding food offered to idols. The eating of this food was the means by which worshippers participated in the sacrifices offered to those pagan gods. Through these chapters, St. Paul gives a variety of reasons why all of the members of the Christian community at Corinth must abide by the commandments against such participation as re-affirmed at the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15. In the opening chapter of this discussion, chapter 8, St. Paul makes a distinction between stronger and weaker brethren. This distinction understood rather casually, is employed all too frequently in both popular and pastoral discussions and debates in a way that belies the actual use to which St. Paul puts it. All too often, this distinction is used in order to create a sort of tyranny of the minority within communities or to justify judgmentalism of one group against another. In some cases, these misuses of St. Paul’s argument even involve a person identifying himself as the “weaker brother.” The point which the apostle is here making, however, is important. It is far too important to be lost to misuse and misapplication.

The language of brethren, we know from both St. Paul’s epistles and the Acts of the Apostles, was the common language of the first century to refer to members of Christian communities. This family language predominated as the means for understanding the relationship between Christians as brothers and sisters. The relationship between the apostles and presbyters in the early church was seen in paternal terms, fathers and children (eg. 1 Cor 4:15; 1 John 2:1, 12, 18, 28; 3:7, 18; 4:4; 5:21). Much of St. Paul’s moral teaching falls into the genre of household regulation. This is most obvious when St. Paul is speaking about the roles of husbands and wives, parents and children. It influences, however, all of St. Paul’s practical teaching precisely because he sees the church as a family and himself as having been given a paternal role in that family. He instructs as a father governing his household.

St. Paul speaks first to the “stronger brothers,” at least by comparison, in chapter 8. The way in which he speaks to them, however, clearly entails that they are not, in actuality, stronger or superior to their brethren in any real way. What they seem to believe makes them superior is certain “knowledge” which they possess which others within the community do not. This knowledge makes them more advanced than their brethren (1 Cor 8:1). St. Paul is quick to attack this conception, however, pointing out that this supposed knowledge produces pride and not love, sin rather than spiritual fruit. Further, he describes these brethren as those who “imagine that they know something” (v. 2). In contrast to those who love God and therefore are known by him (v. 3).

It is within this context that St. Paul addresses what it is that these members of the community claim to know. The verses in which their view is described are the victim of frequent mistranslation. The knowledge which these brethren claim to possess is that “an idol is nothing” and that “there is no God but one” (v. 4). This implies that these brethren are arguing based on the basic principle of the faith that Yahweh, the God of Israel, is the only one worthy of worship that idols and the demonic entities which they represent and which dwell in them are nothing and worthless. They then apply this to mean that the pagan rites are irrelevant and it doesn’t matter if they eat of the sacrifices. It is worth noting here that St. Paul returns to and disputes these claims quite directly in chapter 10. This is, after all, the beginning of his discussion and not the end. In the end, he is quite clear that what the nations offer in sacrifices they offer to demons and that to participate in these sacrifices is to commune with demons (1 Cor 10:19-22). St. Paul’s affirmation that an idol is nothing, then, is seen to be a confirmation that these gods do not represent beings comparable to Yahweh, not agreement that idolatry is somehow no longer a moral problem.

In chapter 8, however, St. Paul takes a different preliminary approach to these brethren. First, he corrects their view of God, their theology proper. He says that “there are many things called gods in heaven or on earth, indeed there are many gods and many lords” (1 Cor 8:5). St. Paul is here acknowledging the existence of the demonic powers to which he will return in chapter 10. He goes on to say, “But for us, there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we are, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we are” (v. 6). Though perhaps not obvious in English translation, this verse is St. Paul’s reworking of the Greek text of the central prayer of Judaism, the Shema, “Hear, O Israel, Yahweh your God, Yahweh is one” (Deut 6:4).

St. Paul has altered this text by inserting Christ into this statement of the oneness of God. The apostle sees neither the existence of other spiritual beings, angelic and demonic, nor the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, as contradictory to or impinging upon this affirmation of Israelite religion. Indeed, the final Hebrew word of the Shema, ‘echad‘, translated “one,” means “one” in the sense of unity. It means one in the sense in which Christ uses the word in St. John’s Gospel (10:30; 17:21-23). The Hebrew word for the cardinal numeral “one” is not ‘echad‘ but ‘yachid‘. The latter might be translated as “single” in order to bring out the difference. It is also worth noting that St. Paul’s description of the relationship of the Father and the Son vis a vis creation parallels that described by St. John in the prologue to his Gospel (John 1:1-3).

Having corrected their doctrine, St. Paul then corrects their application. In chapter 8, still at the beginning of his discussion, he offers one compelling reason why, even if these “knowledgeable” brothers were correct, they ought not to eat food which had been offered to an idol, and this is for the sake of their brother who is “weak” (1 Cor 8:7). In what way is this person “weak”? St. Paul first describes them as not having the “knowledge” of the formerly addressed brethren, but he has already lampooned this knowledge at the opening of his discussion. He goes on, however, to describe what is weak as their “conscience” (v. 7, 10). The word here translated as “conscience” is in Greek ‘syneidesis‘. This word describes the faculty of human consciousness which brings together everything received by the five senses as well as that perceived by the mind (‘nous‘). The “conscience” does this either well or poorly resulting in choosing good or evil respectively. To have a weak conscience, then, is to have difficulty discerning the good and doing it. It means being prone to falling into sin and thereby away from Christ.

This means that the “weaker brother” does not have weak faith in the sense that it is often described. It is not that this brother doesn’t believe hard enough. It is not that he has doubts about the existence of God or the truth of some doctrine. The former case simply did not exist in the ancient world. It is certainly not that this weak brother was easily offended or overly sensitive such that St. Paul is advising the rest of the community to walk on eggshells around him or play along with his prejudices and moralisms. It is that this man or woman is prone to falling into some particular sin. In this case, it is someone prone to fall back into the idolatrous pagan worship out of which they had come in converting to follow Christ (v. 10).

The person is rather weak in regard to faithfulness or loyalty. Here St. Paul describes sin as “stumbling” (v. 13). He warns that the authority which these “knowledgeable” persons claim for themselves may become a “stumbling block” for their brothers (v. 9). If to fall into sin is to stumble, then what these brothers whom St. Paul is critiquing are doing is tripping them. What St. Paul here instructs is grounded in the teaching of Christ himself in the Gospels (Mark 9:42; Luke 17:1). St. Paul addresses this theme also in his Epistle to the Romans (14:13-23).

St. Paul’s theme here is the same as at the beginning of the chapter, in contrasting love and pride. Christ loved these brethren so much that he was willing to die for them, to free them from the powers of sin and death as well as the demonic beings whom they had worshipped (v. 11). The “knowledgeable,” on the other hand, are too puffed up with pride in their knowledge and authority to care if they are leading some of their brethren to destruction in falling away from Christ. This is not just a sin against these brothers but against Christ himself (v. 12, cf. Matt 25:45).

St. Paul concludes by stating that rather than lead his brother into sin, he would give up eating meat entirely (v. 13). Indeed, this likely would have been required of most of the Corinthian Christians as Corinth was one of several cities within the Roman Empire known to have nearly all of its meat in the marketplace supplied from the temples of idols. But as St. Paul had already established, there was no spiritual benefit of concerning certain types of food over others in terms of one’s daily diet such that one would truly suffer from giving up meat (v. 8).

The apostle, here, is then reissuing a warning delivered by Christ to his disciples and apostles. The person who encourages, excuses, or guides a weaker, struggling brother in Christ toward sin is more liable to a more severe judgment than the confused and struggling Christian who falls into the sin. The promotion of sin, even casually through one’s actions, but most certainly with one’s words, is a sort of anti-evangelism. It is to ally one’s self with the demonic powers seeking to ensnare and destroy one’s fellow Christians (1 Pet 5:8). St. Paul is not warning against upsetting someone or confronting their sin. Nearly the entirety of 1 Corinthians is the apostle doing precisely that to the Christian of the Corinthian community. Rather, he is doing the opposite. He is issuing a dire warning that encouraging the weak to sin or go on sinning is a diabolical act that cuts that person off from Christ and brings about condemnation.

Thank you Father for the clarification of what is meant by “the weaker brother”.

I remember when I first read St Paul’s words re the “strong” and the “weak”. Immediately impressed on my mind was a picture of one who was less educated, less well read, in need of the good example set by the ones who ‘know’ – the ‘stronger’. And further, that is how those verses understood by all in our church. So it is almost to be expected that you frequently analyze yourself to determine if you are the weaker or the stronger. Because of this unhelpful “rating system”, it was easy to conclude that the latter was “better than” the former. There develops a competitiveness, and worse envy and resentment. Not many wanted to identify with the weaker brother.

Even with St Paul’s words that “they imagine they know something” and “knowledge puffs up”, the entire context you lay out for us here in this post was completely missed.

So, if I understand correctly (thinking aloud here), those who St Paul called ‘stronger’ were actually misleading (tripping up) those who were careful to avoid food offered to idols. Rather than the weak brother’s lack of knowledge, it was rather the weakness of conscience that posed the danger of falling into the temptation of idolatry.

You describe this weakness here:

“human consciousness which brings together everything received by the five senses…does this either well or poorly resulting in choosing good or evil respectively. To have a weak conscience, then, is to have difficulty discerning the good and doing it.”

Here I thought of St Maximus the Confessor’s teaching on the gnomic will. If I track this correctly, it seems that irrespective of a person’s degree of knowledge, we all are prone to this weakness of conscience.

Admittedly, I do attempt to level out the playing field. Perhaps this what St Paul alludes to when he says not to think so highly of yourself, “lest you fall”?

Father, would you give an example of something that a knowledgeable/strong modern day Christian would do that would be a stumbling block for some others?

I have in mind the abuse from a person of high standing, who perhaps twists scripture to suit their ‘sin’. Someone who is ‘a pillar’ of a church. I mention the extreme, but also wonder about the more subtle yet “diabolical” acts.

Many thanks, as always.

I’ve always felt that in order to properly read scripture one must understand the linguistic nuance of the original text as well as the cultural and historical context to which the passage in question refers. The problem is that I have effectively zero historical and cultural knowledge about 1st century Palestine, and my facility with original texts of that period is limited to say the least. That’s why it’s such a treat to read your blog posts Fr. Stephen. You express my feelings far more eloquently than I ever could. Thank you so much.