The latter portion of the Book of Parables (chapters 60-69) within the text of 1 Enoch incorporates a ‘Book of Noah’, an independent Enochic tradition already in written form by the time it was incorporated into the Book of Enoch’s text. This is evident from a few features of the text. First and foremost, the speaker shifts from Enoch to his descendant Noah. Occasionally the speaker shifts briefly back to Enoch but in each of these cases, the remark involving Enoch appears to be a later editorial insertion. If these were merely traditions regarding Noah in an oral form, the composer of the Book of Parables would have felt free to adapt and streamline it, fitting it into the overall narrative as he did with all of the other Enochic traditions incorporated into the text. That he felt the need to preserve the Book of Noah so intact despite its awkward interface with the other material implies that the traditions contained therein were already in a settled form. Within oral transmission, it is taking on a written form which settles traditions in this way. There is a ‘Book of Noah’ mentioned within the Book of Jubilees (10:13; 21:10) which seems to correspond in content to this Enochic material. While this may seem like scholarly ephemera regarding the composition history of 1 Enoch, it is important for two reasons. First, it marks the Book of Noah as earlier, by at least a century, than the rest of the Book of Parables, pushing it back into at least the second century BC. Second, it means that the material within the Book of Noah has two contexts. As preserved in 1 Enoch, it has a function within the Book of Parables and the book as a whole. It also, however, has its own context having previously circled independently and carried enough prominence to merit its preservation here.

The latter portion of the Book of Parables (chapters 60-69) within the text of 1 Enoch incorporates a ‘Book of Noah’, an independent Enochic tradition already in written form by the time it was incorporated into the Book of Enoch’s text. This is evident from a few features of the text. First and foremost, the speaker shifts from Enoch to his descendant Noah. Occasionally the speaker shifts briefly back to Enoch but in each of these cases, the remark involving Enoch appears to be a later editorial insertion. If these were merely traditions regarding Noah in an oral form, the composer of the Book of Parables would have felt free to adapt and streamline it, fitting it into the overall narrative as he did with all of the other Enochic traditions incorporated into the text. That he felt the need to preserve the Book of Noah so intact despite its awkward interface with the other material implies that the traditions contained therein were already in a settled form. Within oral transmission, it is taking on a written form which settles traditions in this way. There is a ‘Book of Noah’ mentioned within the Book of Jubilees (10:13; 21:10) which seems to correspond in content to this Enochic material. While this may seem like scholarly ephemera regarding the composition history of 1 Enoch, it is important for two reasons. First, it marks the Book of Noah as earlier, by at least a century, than the rest of the Book of Parables, pushing it back into at least the second century BC. Second, it means that the material within the Book of Noah has two contexts. As preserved in 1 Enoch, it has a function within the Book of Parables and the book as a whole. It also, however, has its own context having previously circled independently and carried enough prominence to merit its preservation here.

Chapter 60 begins with the shift to Noah as the speaker in his 500th year. This transition is a bit awkward as the first verse is clearly tailored to attempt to integrate the Noah material into the Book of Parables. By verse 8, however, Noah clearly refers to Enoch as his grandfather, the seventh from Adam. A vision received by Noah immediately before the onset of the flood is here incorporated into Enoch’s vision which was the origin of the three parables. Upon receiving the vision of the Ancient of Days enthroned and surrounded by the angelic hosts, Noah experiences the same kind of extreme distress experienced by the Old Testament prophets when receiving their prophetic calls. Here, however, it is described in even more graphic terms with Noah so afraid in the face of the holiness of God that he is said to lose control of his bowels (v. 3). He again describes this as a near-death experience in which he dropped dead and his soul left his body for a moment (v. 4). When brought back to himself by the intervention of St. Michael, Noah is told that until that day, the patience and long-suffering of God had prevailed over the wickedness of man, but that on that day that would change. Built into the life of this text is a comparison, then, between the coming of the flood in Noah’s day and the coming of the Day of the Lord at the end of the age which undergirds much of the New Testament understanding of the delay in Christ’s coming (Matt 24:27-29; Luke 17:26-30; 1 Pet 3:19-20; 2 Pet 3:9; cf. Rom 1:18).

Noah is then told about the coming day of judgment in terms which clearly apply more to the Day of the Lord than the flood which he would experience. Here the flood that Noah will experience himself is seen as a sort of sign or preliminary fulfillment which assures the truth of the greater prophecy of the End of Days. In preparation for that day, Noah sees the Lord of Spirits separate two beasts, Behemoth and Leviathan. Behemoth is an earth beast and is thrown into a desert waste, east of Paradise, named Duidain. The sea beast is Leviathan who is thrown down into the abysses of the sea. These two beasts are described in Job 40:15-41:26. The separation of the two beasts is a polemical inversion of the Babylonian account of creation in which the dragon representing the heavens and that representing the earth come together and mate in order to create the cosmos. Here, the Lord of Spirits separates them and casts them down. While the God of Israel dwells in a lush garden on his holy mountain, the beasts come to reside in the opposite places, the depths of the sea and a desert wasteland. When Noah seeks to understand their identities, he is shown by St. Michael the angelic spirits associated with the winds, the thunders (cf. Rev 10:1-7), the mists and rains, and the other elements of creation. These two beasts, then, are wicked spirits operating within these created elements that have been subjugated to chaos, destruction, and death. Though they as evil spirits are operative in the world until the end, it is at the End of Days that they come back together in order to feed (1 Enoch 60:23). The coming together of the beast from the sea and the beast from the earth at the end is portrayed by St. John in his Apocalypse (Rev 13:1-18). Both of these spiritual forces, of tyranny on one hand and chaos on the other, are operative in the world but will be fully revealed in the last days.

In addition to the broad description of their character and activity, the two beasts draw directly upon Ancient Near Eastern divine depictions, i.e. pagan gods. Behemoth is the plural form of the Hebrew ‘behema‘, a word which means a beast, an ox, or cattle. The plural is used as a superlative, so this would be the ‘Great Beast’, the ‘Great Ox’, or the ‘Great Bull’. Every culture in the Ancient Near East made use of this ‘Bull of Heaven’ imagery to express the power of their gods. Female gods are frequently described as heifers, younger gods, divine sons such as Baal, as calves. The most common form of idolatry practiced by ancient Israel surrounded this ‘bull’ and ‘calf’ imagery. Leviathan, likewise, is an ancient demonic being, derived by way of ‘Lotan’ from the Ugaritic ‘Litanu’. The name likely finds its origin in the verb ‘to writhe’ (as the Arabic ‘lawiyu‘) related to Leviathan’s traditional depiction as a seven-headed sea serpent. As a spiritual being, Leviathan is an embodiment of chaos and destruction. In Baal myth, she is slain by Baal himself to establish order in the world. She therefore typically appears in the Scriptures within anti-Baal polemic texts. Job 3:8 describes the wicked who tempt the patience of Yahweh the God of Israel as those who seek to ‘rouse Leviathan’ thereby bringing about the final judgment. Psalm 74 takes the great feat accomplished supposedly by Baal and ascribes it instead to Yahweh (v. 14). Unlike the parallel Baal and Marduk traditions, however, the God of Israel slays Leviathan for the benefit of humanity out of love and compassion for mankind. Other texts belittle Baal’s accomplishment by having Yahweh treat Leviathan like a fish he catches (Job 41:1) or as a pet with which he plays (Ps 104:26). Isaiah refers to the tradition again of Leviathan rising in the last days and describes Yahweh slaying her with a sword, putting to an end her power over the nations (27:1).

Noah then sees a vision, parallel to the preceding visions of Enoch, of the final judgment. The Elect One is seated on the throne of the Lord of Spirits’ glory by the Lord of Spirits himself (1 Enoch 62:2). Before this judgment, all of the dead are raised. Every human person who has ever lived is raised regardless of the means of their demise or the status of their remains. Not one human is lost (61:5; cf. Rev 20:12-13). Nonetheless, the focus here of judgment is not the wicked among humanity but the rulers and possessors of the earth. It is these principalities and powers who are the focus of judgment, not the humans whom they misled. The punishment of these latter is to share the fate ordained for the former (1 Enoch 62:9-13; 63:1-11). These are distinguished from another group of spirits which Noah sees suffering the same punishment, namely the Watchers (64:1-2). The Book of Enoch in all of its parts describes not one but multiple spiritual rebellions and a variety of evil spiritual forces with different origins for their evil.

Throughout the Book of Parables, the Son of Man is the Elect One and the Righteous One. He has existed from the beginning but was hidden in the presence of the might of the Most High (62:7). In past times, he was revealed only to the elect before his coming revelation as the Messiah (cf. Col 1:25-26; John 1:1-2; 18). At this revelation, he will gather the elect and the righteous to dwell with him forever (1 Enoch 61:3-4; 62:8). While it may be immediately tempting to understand ‘the elect’ and ‘the righteous’ here collocated in terms of modern Protestant theological use of those categories, a number of features of the text of 1 Enoch make this impossible. The Book of Parables describes those humans who are going to be punished along with the powers and principalities who ruled over them as “their [the demons] elect and beloved” (56:3-4). “Elect” in Second Temple Jewish literature is not a way of describing a group or person selected out of a group. Obviously, the Son of Man in 1 Enoch was not selected out of some group of sons for that purpose. He is unique. This is in keeping with the election of Israel in Scripture. Israel was not one of the nations (as listed in Genesis 10) who was selected over against all the others. Rather, Israel was unique over against the nations.

One should not conclude then, from the language of the Book of Enoch, that the Lord of Spirits on one side and the powers and principalities on the other ‘picked teams’ at some point in the past. Rather, the terms ‘righteous’ and ‘beloved’ are key here. The language of election is language of imaging and of sonship, in particular of firstborn status. The Son of Man is the Elect One because he is the image and Son of the Lord of Spirits par excellence. His elect are those who, by imaging him, participate in his righteousness, are justified, and so become sons of God. The elect and beloved of the demonic powers, then, are those who image them upon the earth, participate in their rebellion and are corrupted by it, and so become their children. It is by this reasoning that those spiritual powers who have not rebelled can be called ‘elect angels’ (cf. 1 Tim 5:21). This understanding, that there are in the world children of God and of light on the one hand and children of Belial and darkness on the other, is a commonplace of Enochic literature and this status is both actualized and revealed by imaging (1 John 3:1-15).

After this first vision of Noah, he beholds the state of the earth in which he dwelt in his own days, how it was corrupted, and filled with wickedness. He knew that the destruction of the world he saw in his first vision was imminent and so he cries out, seeking wisdom. He cries out not directly to God, however, but to his grandfather Enoch (1 Enoch 65:2-4). Here Enoch is not only someone who was taken into the heavens and given a vision to share with humanity. This would apply to all of the classical Hebrew prophets. Enoch is here seen to have an ongoing role as a member of the council of the Lord of Spirits which surrounds his throne. Enoch is now serving for his descendant Noah the function which the archangels served for him in his own apocalyptic journey. Like the archangels, Enoch is not a figure given some sort of special powers in his own right, but rather serves as a messenger for the Lord of Spirits (v. 5-11). This understanding of the departed saints, already present centuries before the Christian era, would continue in the church in the understanding of various appearances of departed saints to those on earth in times of trouble and distress.

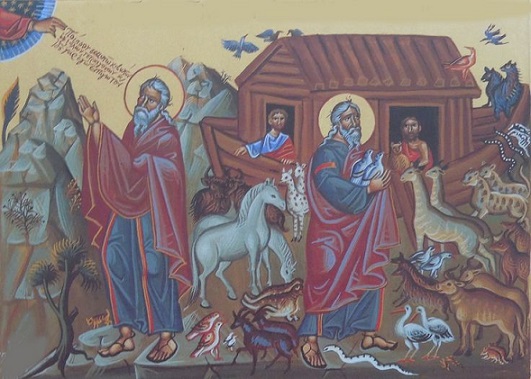

The flood itself is portrayed here as God removing his restraint from the waters. More specifically, the waters as representative of chaos and destruction have spirits of chaos and destruction associated with them. The Lord of Spirits has assigned angels over the powers of the waters to restrain them from destroying the earth (66:1-3). When the restraint is removed, the waters come and destroy everything on earth. God uses the waters, however, to do good. The release of the destructive force of the powers of the waters punishes the spirits upon the earth but heals the body of the earth (67:8). This purification of the earth from the evil produced by the rebellious spirits in the days of Noah, then, is a testimony to a future, greater fulfillment. The day will come when the waters themselves will be purified and healed through the destruction of the powers over them (67:11-12). This purification of the waters from the powers of water is fulfilled at the baptism of Christ. This allows the waters of chaos and death to become the waters of purification, refreshment, and rebirth in baptism (cf. 1 Pet 3:18-22).

The unrepentant wickedness of the fallen Watchers is so abhorrent that even Ss. Michael and Raphael will not intercede for them for to do so would be to take their side against the Lord of Spirits in rebellion (1 Enoch 68:1-5; cf. 1 John 5:16-17). This is followed by another list of the leaders of the rebellious Watchers, numbered at 20 with Azazel separately as a 21st (1 Enoch 69:1-3). Detailed then are the secrets of knowledge that these angelic beings taught to humans in order to further their self-destruction. Notable inclusions are weapons and armor for war, the preservation of secrets in writing, abortion, and magical oaths. The covenant with Noah following the flood is here described as an oath, a pact between the Lord of Spirits and the spirits superintending the various elements of the creation to allow them to function as normal while restraining the forces of chaos and destruction until the End of Days (v. 16-25). The preservation of the world by God, then, is precisely the restraint of supernatural and human evil within the cosmos with that restraint being relaxed as a form of judgment. Humanity is given over in judgment to its own evil devices and to those powers whom it has worshipped and obeyed. The covenant with Noah, then, is not only a promise not to allow another flood of water, but a promise to restrain the forces of wickedness until the last days so that the situation of the days of Noah will not, until then, recur (Gen 8:20-22).

The Book of Parables then concludes with Enoch ascending back to heaven to stand before the divine throne and a parting benediction retained from when it circulated as an independent text. Next week’s post will begin with the next portion of the Book of Enoch, the Book of Luminaries.

Excellent series. Such detail! Thank you, Father.

Would you say, then, that, in the light of the Enoch tradition, when St John recounts, “And I heard another voice from heaven, saying, ‘Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues’,” followed by the recounting of the great wealth (and perversity) of Babylon, that this is a call to the people of God to fully extricate themselves from the influence of and any secret affection or inclination towards the supposedly luxurious, successful, prosperous (yet actually abhorrently wicked and decadent) life promised by Babylon to her people? For in her are found all sorts of merchandise: jewels, arts, crafts, precious metals, etc., including “the bodies and souls of men” (Rev 18:13).

Babylon’s great sin is in seducing God’s people into idolatry, where they were told they could worship God yet enjoy this luxurious life of richness (which causes them to become enslaved to the Babylon system). This in direct contradiction of Christ’s words, “You cannot serve two masters… both God and mammon.”

Yes, there’s a consistent thread of this through the Hebrew Bible, which the Enochic tradition is further developing. See, for example, the Rechabites in Jeremiah 35 (42 in the Greek). St. Peter picks up the thread from the Enochic literature, for example, in 1 Peter 2:11-17. This element, like all the elements of monasticism, are basic parts of the prophetic way of life. Monasticism was not a de novo creation in the fourth century.

Thank you father, this series is really helping me to get an insight into Enoch’s book. I have a question: why is it that even when the powerful of the earth apparently repent from their sins they do not receive forgiveness? This means that they where not truly repented or that it is now too late?

Repentance isn’t regretting the consequences of your actions and not wanting to suffer those consequences. Repentance is the healing and transformation of the whole person. The evil spiritual powers are capable of the former but not the latter.