Any discussion of salvation in general, and that described by St. Paul in particular, will necessarily include the concept of justification. Exactly how justification works was the central argument of the Protestant Reformation in the West. Despite a massive disagreement about its functionality between the Roman church and Protestant groups, they shared, for the most part, a common definition of the term. To be justified was to be made, or declared, to be righteous. Righteousness was something that was possessed and must be possessed in order to enter into eternal life. It must be possessed in complete perfection. Righteousness, therefore, formed a certain bar that needed to be cleared in order to receive eternal life from Christ. In the Roman system, grace and corresponding merit were infused into a human person which, over the course of a lifetime of repentance and good works, would ultimately merit salvation. It was possible to accumulate excess merit through a holy life, which formed the treasury of the merits of the saints, a reservoir of grace dispensed through the Roman church and its pontiff. In the classical Protestant system, in contrast, Christ lived a life of perfect righteous obedience and his righteousness and merit are imputed to believers wholesale and at once upon belief. In both cases, the measure or standard of this righteousness is seen as the perfect keeping of the Mosaic law, the Torah.

Any discussion of salvation in general, and that described by St. Paul in particular, will necessarily include the concept of justification. Exactly how justification works was the central argument of the Protestant Reformation in the West. Despite a massive disagreement about its functionality between the Roman church and Protestant groups, they shared, for the most part, a common definition of the term. To be justified was to be made, or declared, to be righteous. Righteousness was something that was possessed and must be possessed in order to enter into eternal life. It must be possessed in complete perfection. Righteousness, therefore, formed a certain bar that needed to be cleared in order to receive eternal life from Christ. In the Roman system, grace and corresponding merit were infused into a human person which, over the course of a lifetime of repentance and good works, would ultimately merit salvation. It was possible to accumulate excess merit through a holy life, which formed the treasury of the merits of the saints, a reservoir of grace dispensed through the Roman church and its pontiff. In the classical Protestant system, in contrast, Christ lived a life of perfect righteous obedience and his righteousness and merit are imputed to believers wholesale and at once upon belief. In both cases, the measure or standard of this righteousness is seen as the perfect keeping of the Mosaic law, the Torah.

As has already been seen, however, this was never the purpose of the Torah. The promise of theosis, of union with God and his sharing of his life and dominion with humanity, was given to Abraham centuries before the Torah was given and the Torah was not an addition of a whole series of conditions for that promised salvation (Gal 3:17-18). Rather, the Torah was given to deal with sin until Christ came to deal with it permanently. Justification, then, which St. Paul equates with not only the full forgiveness of sins (Rom 4:5-8) but also with becoming sons of God (Rom 8:14-19) cannot come through the Torah. Both of these come through Christ, which is St. Paul’s argument in both Galatians and Romans. Justification does not come through the Torah, neither through a human person keeping it perfectly nor through Christ keeping it as a list of conditions that merit eternal life in the kingdom. It is not a product of anyone’s works of the law (Rom 3:20-28; Gal 2:6; 3:1-10).

It is critically important that St. Paul did not, in contrast, argue that justification was therefore completely passive. He argues that it is the product of faithfulness (Rom 3:28). Faithfulness, loyalty, and allegiance are expressed through not only words but through actions. The Torah is still a guide and an aid to human persons in expressing that faithfulness and a guide to sin and repentance and to worship which is transformative into the likeness of Christ. It is not, however, the means of that transformation in and of itself. It is powerless to do this. The power involved in justification and in the transformation of the human person into one of the sons of God is, according to St. Paul, the Holy Spirit and therefore God himself (Gal 3:1-10). St. Paul’s identification of the power of the Holy Spirit as the source of justification is grounded in two things: the prophecies surrounding the coming of the Spirit upon all flesh in the Scriptures and the definition of justification as St. Paul understands it.

When the promise of salvation was first given to Abraham, it came with a command to walk before Yahweh and be righteous (Gen 17:1). While Abraham was faithful and this was credited to him as righteousness (Gen 15:6), he was neither perfect nor blameless. Nor were his immediate descendants. The Torah was added to deal with human sin, to contain and control it, but could not cure it nor positively transform a human person into the likeness of his creator. One of the most significant promises regarding the new covenant found in the Hebrew Bible is directly related to this problem. Jeremiah speaks of the new covenant thus, “Because this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, declares Yahweh, ‘I will put my Torah within them and I will write it on their hearts. Then I will be their God and they will be my people. Then, no longer will everyone teach his neighbor and every man instruct his brother by saying, ‘Know the Lord.’ They will all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares Yahweh, because I will forgive their iniquity and I will remember their sin no more” (Jer 31/38:33-34).

The Torah is not made irrelevant by the new covenant but is written in the heart of every person who is part of Israel. Because of the Torah’s presence within the heart, all will know Yahweh himself directly. This communion with God and the transformation it brings will result in the removal of sin and iniquity, to the solution of it as a problem rather than merely its management. In speaking of this time of the new covenant, Ezekiel connects the writing of the law upon the heart of the Israelites to their receiving the Spirit: “Because I will take you from among the nations and I will gather you out of all regions. I will bring you into your own land. Then I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you will be clean. I will purify you from all of your filth and from all of your idols. I will give you a new heart and I will put a new Spirit in you. I will take the heart of stone out of your flesh and give you a heart of flesh. I will put my Spirit within you and cause you to walk in my statutes. Then you will keep my judgments and do them. Then you will dwell in the land that I gave to your fathers. Then you will be my people and I will be your God” (Ezek 36:24-28).

The way in which the indwelling of the Spirit, as prophesied in Joel 2:28-32 and fulfilled in Acts 2:1-4, the forgiveness of sins and purification from stain, and the proper role of the Torah are brought together in these texts should be immediately familiar to those familiar with St. Paul’s argument in Romans and Galatians. Ezekiel adds another element, the re-creation of the human heart. This theme of a new creation is also very clearly present in St. Paul’s writings (eg. Gal 6:15; 2 Cor 5:17). It is at this point that these other themes connect with the concept of justification. Due to past debates, justification, as already described, has become laden with legal connotations. There is another usage, however, which is common even in contemporary usage and familiar to anyone who has used a word processor. To justify text is to line it up along one side, the other, or both. In the same way, this term is used, for example, in Daniel to describe the eventual restoration and rededication of the temple, i.e. that the temple will be ‘justified’ (Dan 8:14). Here it is clear that both the elements of cleansing and of being set in order are included.

The Holy Spirit’s role in the re-creation of the human heart is directly parallel to his role in the creation of the world. At the beginning of the creation of the world, the Spirit broods over the waters (Gen 1:2). Creation in Genesis 1 is a series of actions in which God brings order to chaos and then fills his newly established order with life. This is accomplished through the Spirit and through the Word (John 1:3). The justification of a human being, then, the setting of that person in order, is an act of re-creation. The human person who emerges afterward is a new person of a new humanity (Col 3:9-11). This new human person is created in the image of God who is Christ himself (Eph 4:20-24). Bringing about a new birth or re-creating a human heart is not, by definition, something that the Torah can do, even if kept perfectly. This was never its function or intent. It is not why Christ gave it into the hands of Moses.

Through Christ’s incarnation, the entirety of human salvation is accomplished. Our shared humanity is united to God himself in the person of Jesus Christ. The power of death has been stripped from the Devil and all of humanity has been made alive. The powers and principalities which had enslaved the nations have been defeated. Atonement for sin, its purification and the cleansing of its corruption have been accomplished. All of these, however, have an element of definitive fulfillment and an element which will be brought to completion at the end of this age, at Christ’s glorious appearing. Death has been defeated, but it is at Christ’s appearing that all of the dead will rise. The gospel has gone out to the nations and all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to Christ, but the demonic powers have not yet all been confined to the lake of fire prepared for them. This gap between accomplishment and perfection is the result of the third element of man’s salvation, purification of sin and its resulting curse (2 Pet 3:15-16).

As Ezekiel prophetically described, the new covenant is administered and justification takes place through baptism with water and the Holy Spirit. This makes a person a Christian, not only a new person but a new kind of human person. As the Orthodox baptismal service pronounces, “though art justified, thou art sanctified, thou art washed” (1 Cor 6:9-11). Justification, then, is something which can be said to have occurred for the faithful, just as it did for Abraham apart from the Torah (Rom 4:9-12). At the same time, Abraham and his descendants continued to fall prey to sin and its corrupting effects upon themselves and the rest of creation such that the Torah needed to be added (Gal 3:19). Just as the management of ongoing sin was necessary under the old covenant in preparation for the coming of Christ, so also must sin be dealt with when those in the new covenant, though justified and a new creation, fall prey to sin and need to receive once again the forgiveness and purification of Christ’s sacrifice. On one hand, having put on Christ in baptism, the old person is done away with and the new has come into being (2 Cor 5:17). On the other, the old self must continually be put off through repentance (Rom 6:6; Eph 4:22; Col 3:9). It is in the resurrection that our justification will be complete as part of an entirely renewed creation (Rom 4:24-25).

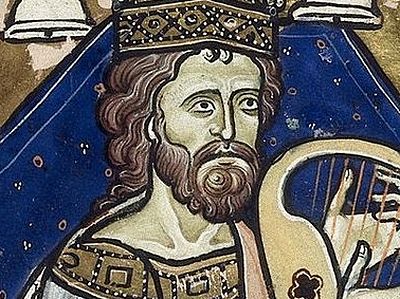

David the prophet and king is remembered by the Church for a number of reasons. Chief among them, however, is his repentance. He has not only given us a model of repentance through his life, but he has given us in Psalm 51 (50 in the Greek numbering) a poetic image of the experience of that repentance and forgiveness, of justification, as it happens within the life of a human person in real-time, in real life. Justification and salvation itself are not theological abstractions or systems or mechanisms, but rather the lived experience of those receiving the promises first made to Abraham and being made alive in Christ.

In the Psalm, David’s experience of his sinfulness and the depths of his corruption is not just a matter of having broken rules. It is a corruption that has infected his very bones (Ps 51:8). Sin and wickedness seem to him knit into the very fiber of his being from his coming into being in his mother’s womb (v. 5). This hearkens back not primarily to David’s literal mother but to Eve, the mother of all living, who brought forth her children into this present world corrupted by human sin. David has not ‘made some mistakes’. He has rebelled against God in hatred (v. 4). His hands are soaked with the blood of those who have become his victims (v. 14). This blood, like Abel’s, cries out to God for justice against David.

The answer to this is for David to be justified. For him to be recreated and set right. He needs to be washed and made clean again from the filth into which he has wallowed (v. 1-2, 7, 9). This washing and cleansing will precede God’s creation of a clean heart within David and the renewal of the presence of his Spirit (v. 10-12). Within him, the Spirit will teach him the law (v. 6). David understands that this will take place through repentance, through his humbling of himself in honesty regarding his sin and wickedness and his state as one accursed (v. 3, 17). It will not come through a mechanical or magical ritual (v. 16). In return, David has but one thing to offer: sacrifices of praise and thanksgiving (v. 14-15, 18-19).

David does promise one further thing if the God who created him will show him his mercy. He promises to teach his fellow sinners the way of salvation (v. 13). He has kept this promise by being the instructor of the faithful for nearly three millennia. St. Paul describes for us the road which leads to salvation through the cross and the grave. King David describes for us his journey down that road. It is a journey which begins in the mire of sin, curse, and corruption and which ends sitting down at table with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Matt 8:11).

An excellent post, Fr. Stephen, thank you. This description of justification fits perfectly with Isaiah’s notion (esp. chs. 40-55) of God’s righteousness—His action in the world, as Judge, to set things right in new creation. Have you written any posts on the dikaiosune theou? For me, studying this theme in Scripture has been the route to understanding Paul’s concept of justification and salvation, as you wrote, not as “theological abstractions or systems or mechanisms, but rather [as] the lived experience of those receiving the promises.” I.e., justification is theosis, not legal standing. Thanks so much for your faithful work in the true faith.

There’s going to be some material on that coming soon.

I appreciate this post as it puts a lot of the “salvation wars” as I call them into a better perspective. However, my experience of such things is highly conditioned by an experience I had when I was first coming into the Church in 1986=87. The Antiochian parishes where I live were doing a common study of “For the Life of the World”. One of the women participating from the other parish than mine had terminal cancer.

I will never forget, sitting on the floor right at her feet when the topic of salvation and justification came up. One man there, a learned and faithful man was asking a lot of questions-similar to the ones above. After he had gone on awhile she addressed him thus: “You are making it too complicated. Don’t worry, you’ll get there.”

It is quite difficult to express the power of those words. At that point she was already about half into the next world and in a place of great peace, even joy. Her words were spoken from that place with such compassion, understanding and depth. They were not just a sentimental hope. Her peace washed over me sitting there. It has never quite left.

Not long afterwards she reposed. I was told that when she received communion the final time at her parish, she went forward with her arms spread wide looking up with a serene smile on her face which was quite a contrast to how she normally went forward.

She was an example of justification I think. So whenever I have a tendency to start chewing on the matter too much which is quite easy for me, her words come back to me: “You are making it too complicated” While I cannot say for myself with the authority the rest of her words: “You’ll get there” such an out come is a settled hope with me because of the way in which she spoke them.

Repentance is absolutely essential, deep repentance in the manner of David, the King. Not all will “get there” unfortunately. She was faithful in the life of the Church, she was speaking to a man who is faithful as well. I have no question about her or the man to whom she spoke. My hope in the outcome rests in being as faithful as I can. I hope to be ready.

God’s mercy endures for ever.

Father great post! I wondered how you would respond to this verse

Matthew 5:20

For I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.

Does this not relate to a need of law keeping to enter Heaven?

Blessings

Stephen

I would say that it says the exact opposite. The Pharisees were the masters of law-keeping. Christ is pointing to the same misunderstanding as St. Paul here. The commandments of the Torah are not a series of conditions to be met in order to inherit eternal life, namely the re-creation of humanity in his image through the Holy Spirit.

Wonderful essay Fr. De Young! I love reading your blog, and I hope that one day you collect your writing and publish it. I would enjoy having all these essays and articles in book format!

Thank you very much P. Stephen ! I recently asked the Lord to illuminate my darkness and here I am today discovering your edifying text, which opens up so much the mind and the heart, and which creates the need to enter more deeply into meaning, knowledge.

Even joy stimulates the desire to know the truth, all that is right and good ….

Glory be to God !

I am not a scholar like you, but I picked up some ecclesiastical Greek through osmosis serving in my youth as an altar boy at a very ethnic Greek Orthodox parish. It is my understanding that “justification” in Greek is δικαιοσύνη (Dhikeosini), but that same word can also be translated as “righteousness”. In English, of course, these two words have very different connotations, and the theology one presents depends on the translation choice one makes. I’m not suggesting that Western Christians adapt their translations to fit their theology; I’m suggesting quite the opposite, namely that their theological understanding of the text comes from a different linguistic tradition, and this naturally leads them to produce a different translation. What I’d like to know is how Western protestants who know Biblical Greek defend their notions of justification given the linguistic and cultural evidence you present. Since you were formerly a Protestant pastor and scholar, I think you might have some insight on this.