In our modern understanding of being, being is commonly opposed to nothingness. Something exists and by this we mean has some sort of material reality, it is a thing, or it does not exist, meaning that it is imaginary and has no real time space existence. The difficulty of discussing the existence of God as ‘a being’ within this paradigm is what has created most of the unprofitable discussion surrounding atheism in our society. This understanding was preceded for centuries, particularly in Western thought, by an understanding initiated by Plato and further elaborated by the Middle and Neo-Platonists. Platonism opposed being not with some concept of non-being that equated with non-existence, but with becoming. There are things which simply are. By virtue of this, they are superior to everything which is in motion or a process of change which is becoming something but is to whatever degree not yet that thing. This makes stasis, for Platonism, one of the highest virtues. When this conception was integrated into Christianity, it produced an understanding of being as a chain, at which the simple, immutable God stood at the top and the bare elements of creation lay at the bottom. All things, however, share being along a continuum. Aristotle’s particular variation on this understanding reveals to a certain extent the ancient view which preceded it. He speaks of potentiality and actuality. “Prime matter” consists entirely of potential. It can be formed into anything but is not yet anything. On the other end of the chain would be a being of pure actuality, unable to change, which is the language which Thomas applies to the Christian God. Once again, all created things and their creator are connected by being itself and are therefore related to one another by way of analogy.

In our modern understanding of being, being is commonly opposed to nothingness. Something exists and by this we mean has some sort of material reality, it is a thing, or it does not exist, meaning that it is imaginary and has no real time space existence. The difficulty of discussing the existence of God as ‘a being’ within this paradigm is what has created most of the unprofitable discussion surrounding atheism in our society. This understanding was preceded for centuries, particularly in Western thought, by an understanding initiated by Plato and further elaborated by the Middle and Neo-Platonists. Platonism opposed being not with some concept of non-being that equated with non-existence, but with becoming. There are things which simply are. By virtue of this, they are superior to everything which is in motion or a process of change which is becoming something but is to whatever degree not yet that thing. This makes stasis, for Platonism, one of the highest virtues. When this conception was integrated into Christianity, it produced an understanding of being as a chain, at which the simple, immutable God stood at the top and the bare elements of creation lay at the bottom. All things, however, share being along a continuum. Aristotle’s particular variation on this understanding reveals to a certain extent the ancient view which preceded it. He speaks of potentiality and actuality. “Prime matter” consists entirely of potential. It can be formed into anything but is not yet anything. On the other end of the chain would be a being of pure actuality, unable to change, which is the language which Thomas applies to the Christian God. Once again, all created things and their creator are connected by being itself and are therefore related to one another by way of analogy.

In the most ancient understanding, however, which includes that of the scriptures, being is opposed not to non-existence or fiction. Neither is being as a stasis opposed to those things which are in a process of change or growth or flux. Rather, being is opposed to chaos. To exist is to exist within a web of relationships which create meaning and purpose. It is to be ordered and structured. When a tower collapses into rubble, all of the constituent material of the tower is still there in the form of the rubble. The tower, however, no longer exists. When an animal dies, its body dissolves into the earth, returning to its component elements, but the animal no longer exists. While people and their descendants may continue to exist after the collapse or destruction of a nation, the nation itself no longer exists following such an event.

That God brought all things from the nothingness into being is the clear teaching of the scriptures and the Orthodox Church. There are places within the scriptures, however, in which creation is described in other ways. In Genesis 1, the creation of the world is described as being from nothing, but that nothing is primordial chaos rather than a timeless, spaceless void if such a thing can even be conceived by human persons. Rather, the earth is formless and empty (Gen 1:2). This is further described as darkness above and the watery abyss below. Over the following sequence of days, God gives structure to the primal elements. Over the first three days, this takes the form of the organization of these elements to create spaces. The creation of time from timelessness is not described, but on the first day, structure is given to time beginning with the day itself, evening and morning. On the second day, the spaces of the heavens and the seas are created. On the third day, the space of the dry ground is created. These spaces are in neither ascending nor descending order. In ancient experience, the heavens are the dwelling place of divine beings and manifest a perfect order. The land is the realm to which humans attempt to establish order. The seas, where no human can exist, continues to represent chaos and death, the two of which are closely linked.

On days four through six, God proceeds to fill each of these spaces in turn, to solve the second problem, of emptiness. The heavens are filled with the sun, moon, and stars. The skies are filled with birds and the seas with fish and creeping things innumerable. The land is finally filled with animal life and finally humanity. Contained within the story of the creation of humanity, however, is the idea that God’s creating work is not complete. Humanity is created and commanded to fill the earth and subdue it (1:28). Human persons are created to continue this work of giving order to the creation and filling it with life. This ordering of the world forms the scriptural understanding of justice and expresses itself in the Torah in the form of commandments, through the keeping of which human life will bring that structure to the world as a whole. Sin as a force is opposed to this order and seeks to destroy it, reducing human life to chaos and death. It is only through these structures, however, that life can have meaning and purpose. Judgment, in Hebrew and Aramaic the same word as ‘justice,’ is the establishment or reestablishment of this order on earth. Justification is the setting of things or persons back into the proper order of things and the correct set of relationships with their creator and the rest of the creation. It represents a new creative act.

Therefore, what it means to “live” or even to “exist” is to participate in these correctly ordered relationships with other human persons, the rest of the creation, and preeminently with God, the Holy Trinity. “This, then, is eternal life, that they might know you, the one true God, and the one whom you have sent, Jesus Christ” (John 17:3). Because these relationships are definitional to life and existence, without them there can be no concept of purpose or meaning to brute material existence. Conceptually, these are inseparable. Therefore, the breaking of these relationships through sin, the disintegration of good order, or exile constitute death and non-existence. The wilderness, that part of the world to which order has not yet been applied, remains in this state of chaos and so is associated with non-being and death. It is ambiguous through the Torah as to whether being ‘cut off from among the people’ represents death or exile precisely because in context, these were the same thing. The sea continues to represent the same principles, which is why it ceases to exist in the new heavens and the new earth (Rev 21:1). Likewise, the darkness of night, the time of sin and violence, ceases to exist (cf. John 3:19; Rev 21:25).

These ancient concepts of life and death, being and non-existence, are critically important in order to understand what the scriptures teach regarding the state of eternal condemnation. While commonly still called ‘hell,’ that concept owes more to Anglo-Saxon paganism’s understanding of the netherworld than to ancient Christianity. At the expulsion from Paradise, God cut off humanity from the tree of life and allowed death to reign over him in order that humanity might not suffer the same fate as the rebellious heavenly powers (Gen 3:22-23). Having been gifted with freedom and immortality, when these powers chose in their turn to rebel against their creator they were left permanently in a state of death, corruption, and self-imposed exile from the kingdom. Material life in the still disordered world ending in death creates for human persons the opportunity for repentance and transformation with immortality being a gift granted to humanity by Christ, after the conclusion of his defeat of death after his final judgment has established order within the creation as a whole (Ecc 3:11; Wis 3:1-4; 1 Cor 15:23-26).

The core of scripture’s understanding of eternal condemnation for humanity, then, is that those who have failed to use this life for repentance and transformation through Christ will share in the fate of these rebellious spiritual beings after whom they have followed (Matt 25:41; Rev 20:14; 21:8). Reading the many horrifying descriptions in scripture of this eternal state against the background of modern understandings of existence and non-existence has frequently produced theological errors, even heresy. Some have read the imagery of death and destruction in a modern literal way and so argued for annihilationism, that the souls of those not destined for eternal life simply vanish like vapor. This literalism breaks down, amongst other places, once it is understood that the life of the soul, obviously, is not biological. Neither, therefore, can the death of the soul be conceived of as the cessation of biological life. Universalism operates from either a Platonic or modern understanding of these terms, likewise. From a Platonic conception, being is something which all things possess in degrees and constitutes not only a good, but a connection to God himself, the Good. This then is interpreted to impose a sort of obligation on God to redeem the good within all things. Origen took this universalist heresy to the ultimate conclusion that because the demonic powers exist, they too must be reconciled to God.

On the other hand, some followers of universalism see the eternal existence of saints and of the condemned as univocal. Because they are working from categories of existence and non-existence and reject annihilationism, the two states are seen as eternal good life and eternal bad life, with God as the agent who is actively blessing one group and actively torturing the other. With this flawed paradigm established, they rightly find the latter to be abhorrent in the portrayal which it gives of God. That God would save all of humanity, either immediately or eventually, is therefore their only possible conclusion in order to preserve the character of the Triune God as portrayed by scripture and the Orthodox Church. That this argument is based on flawed premises is clear in a number of ways, not least among them that in this conception, as in that of penal substitutionary atonement, God is seen to primarily save human persons from himself.

Once the ancient understandings of life and existence on the one hand and death and destruction on the other which underly the scriptures are understood, however, the Biblical language concerning the state of eternal condemnation, while still frighteningly terrible, comes into focus. To have eternal life in this age and the age to come, to live and to truly exist, to have meaning and purpose, is to come to know God in the person of Jesus Christ and so to be in right relationship with other human persons and the whole created order. This is not a stasis but an eternal movement toward God in which a human person will be established forever at the judgment seat of Christ in the day of his glorious appearing. In contrast, to die as Adam surely did in the day of which he ate of the tree, to be destroyed, is to alienate one’s self from Christ. It is to alienate one’s self from other human persons. It is to rebel against the order of God’s creation. This way of living in this age drains all meaning and purpose from life. It renders the world unintelligible chaos. It creates the truest form of self-imposed suffering. Those who pursue this path to the end of their life in this age find it also to be an eternal movement away from God in which they are established forever at the judgment seat of Christ in the day of his glorious appearing. Life, existence, meaning, and purpose are constitutive elements of what it means to be a human being (Gen 2:7; 1 Cor 15:45). To come to know God in Christ and to receive eternal life is to become truly human To eternally cut one’s self off from Christ and his kingdom, then, represents the ultimate diminution of humanity, to cease to exist in any meaningful or purposeful way as human.

Thankyou for your very in-depth article! While my faith is somewhat very simple and lacking in some areas, I could not help but think about the school systems in place that seem to be growing and developing for those in a certain frame of mind and blindness who cannot see the system causing chaos leading to destruction. On the other hand, there are those who are in a healthier frame of mind with clear vision who are striving for a system with structure, order and more specifically, morals. Both systems are struggling to win while also working together. (like the weeds and darnell I suppose)

I had a conversation with a priest today about the corruption and lack of morals in schools and libraries and how even the youngest children are being exposed to immoral reading material, videos and program. Should parents continue to fight and try to work together in this environment that is affecting children as well as the careers of the teachers who have a high standard of morals? Or should they get out now asap and bring education into the home by home-schooling or better yet, have an Orthodox school in their area where all Orthodox children can come together without this burden of deception and destruction hanging over their head each day leading to depression and worry? One priest told me it would take a million $ to get an Orthodox School up and running in the area and we need to begin to pray hard for this. True, we do with no time wasted before the children are wasted and Orthodox people lose interest in teaching as a career because of the environment they have to go to – never being allowed to speak against what is going on or they will be dismissed. If only there was an Orthodox world-wide drive for donations to build up the Orthodox Schools. Then there might be some freedom from this oppressive situation!

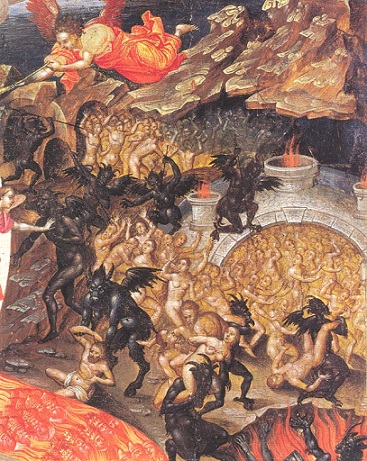

The picture that goes with this article, shows clearly how the demons are attacking people relentlessly and I think we need to pray very hard now – not later – for God to burst into this darkness and bring His beautiful light which will save us. God bless!

Thank you, Father.

This is a very good framework for understanding humanity’s existence in the afterlife, but I’m not sure how the notion of aerial toll houses fits into this framework (i.e. what occurs during the transition from this life to the next). Could you elaborate on how you think toll houses fit into this framework, or do you not subscribe to the notion of toll houses at all? I know many Orthodox Christians prefer not to dwell on aerial toll houses, but if you read Orthodox writings about the afterlife, they’re unavoidable. I don’t want to get you into any trouble with your bishop, but to the extent that you could share your understanding of the the toll houses, I’d very much appreciate it. For the record, I’m skeptical about them, but I’m not a scholar like you nor a theologian, so I choose not to make any assertions about them either way.

Tollhouses can quickly, as you indicate, become a rabbit hole. So, without going down it, I’ll just say this. As a Biblical scholar dealing with the scriptures in their original context of Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity, I never have occasion to encounter tollhouse doctrine. So it is, at best, outside of my field.

Peace…..already in a short time, the few responses have quite a variety of insight! Interesting…..God bless!

Your blessing, Father.

Dear Father Stephen,

Once again I thank you for your teachings, and now, for this present one. I have had to “sit on it” for a while because of the difficulty of gathering my thoughts in a way that I can communicate clearly.

One of the things Orthodoxy has shown me is that because of the great depth of the Faith, I must take the time to contemplate many of its truths, rather than dismiss those that pose a great challenge on account of prior conclusions I may have mistakenly made. I have also found that in the many questions that I have, there are times where I am not given clear and concise answers.

Regarding the matter of salvation, perhaps it is clear to some people, more than it is to myself, in what manner will be the consummation of this age, when all creation will be one in Christ. What will this look like, who will or will not be saved, how exactly will this appear, and what of our final end (is there indeed a finality? what does this mean?). Though I know what scripture says, all is not entirely clear to me.

Considering the concepts of “person” and “personal salvation”, there is at the same time, created in God’s image, a certain unity between us all. Yet this unity, with God and man, has been terribly shattered. As goodness is effectual upon all, so too our sins. We share the burden and are our brothers’ keeper. And we are saved only through Christ. And so I pray for mercy for all, as if a part of myself.

We intercede repeatedly throughout the Liturgy. I have hope and pray that none should perish, surely through the workings of the Spirit, whose presence in the world is still now drawing all things to Christ. I intercede in this way, not to put God under obligation, but because it is undeniable that I myself who have been granted such bountiful mercy, am in no way deserving of such. By God’s grace I have come to believe. So I pray for mercy for all.

I am not so much of a learned person that I am completely cognizant of the millions of souls that do not know Jesus as Lord, but I do know there are many. I am not able to conclude that each one will be condemned eternally because they, in their mundane existence, may not have had the opportunity, for reasons I have no way of knowing, to repent and turn to Christ. I only know that it is Christ who draws all things to Himself. I don’t think He ever stops doing this. Ever.

At the same time He will not coerce, He will not force one to turn to Him. But there is a moment, unknown in its mystery, and impossible to subjectively describe, where He touches the hearts, imparting His grace upon those who are far from Him. In the Church teaching of synergy, we understand that we are given the freedom to turn to Him, or not. But even our part is not apart from the grace of God.

Based on my own experience I can not fathom how, once the heart is touched by the grace and mercy of Christ our God, one can reject Him. I just am at a loss. Can a heart be so far gone in its hardness, can the eye of the soul be so utterly closed off, that it can not recognize the presence of the Almighty, and respond in utter realization of our helplessness before Him? How can this be? These are my questions. These are my thoughts and prayers that I believe are not rejected by God and the Saints to whom I pray. As I pray for myself, I pray to God for those far from Him. I can get pretty far from Him myself. I know all to well the weakness of my flesh. And I know His boundless mercy.

And so, this is what I carry in my heart as I read and learn and try to comprehend more and more the teachings of the Church. In their fullness I know I shall ever be learning. I welcome the opportunity to learn from different perspectives. You offer that, Father Stephen, in your teachings in view of Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity. It dawned on me, after reading your response (above) to Michael Skarpelos, why I was drawn to your teachings from the very first time(s) I read your blog posts. It is because I have not come across anyone who teaches from that perspective. And because I have not come across very many (actually, none) who teach the OT from that perspective as well. It is a blessing that you do so. I very much desire to know more about the OT and have found your teachings have met that desire through this very blog site.

If I had to be concise in describing the difference in your teachings, aside from using the words “Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity”, I would say you teach from a Semitic perspective. It has a different focus than the philosophical/Platonic perspective that a portion of our Fathers spoke from and related to. Yet both “sides” took the effort to fully integrate these perspectives into the teachings of the Apostles in the “right (orthodox)” interpretation of the Faith, according to the revelation of God in Christ. I see no difference, therefore, in the fundamental teachings of the Faith from either perspective. To me, the only difference is the “language”. The neo-Platonists spoke according to culture of their day who were steeped in a variety of philosophical thought. It is what was given them to seek an understanding of “purpose”. More than that, in “being” and “existence”.

I can understand how such a perspective can be misconstrued and used to give a false representation of a Supreme Being. You explain it well, how especially in western thought, “being” was thought of in a manner of ascent/descent, the highest “Being” being that of God. But the neo-Platonists of our faith (here I think of the Cappadocians, St. Dionysius the Areopagite, St Maximus the Confessor), as I understand, speak of God as One who stands apart from “all being”. He is not on a continuum of “beings” where He stands “at the top”. I think it is this where some of those of the Protestant faith mistakenly criticize Orthodoxy, who say we draw our faith strictly from philosophy rather than from the Bible. This is a misunderstanding of the task our Fathers strove so tirelessly for, to identify and dogmatically declare what it is that the Christian faith espouses, where they “spoke” Theology using philosophical language,

I can recognize in our 4th century (and beyond) Fathers’ use of Platonic language, a reference to “chaos” without using that biblical word as a descriptive. I think “chaos” is couched in terms such as “being and non-being” and its’ descriptive is as you say here: “To exist [to be] is to exist [to be] within a web of relationships which create meaning and purpose”. You make similar points throughout your article. It is my understanding that when we live apart from our intended meaning and purpose it is in a very real sense not living at all…”not-being”.

Please know, Father, that in the contents of this lengthy comment, I offer no challenge or disagreement. I only share my understanding as best I can. I am thankful for the opportunity to further contemplate. The entirety of this post offers that very thing.

There is one thing though, that have great pause in, which I previously alluded to. It is the certainty of eternal condemnation. There are Saints and Fathers of the Church that hope in a full restoration of all things. St Paul uses the language of restoration (apokatastasis) as well as condemnation. I consider both. And pray for the former.

Thus, the ending of your article left me with a nagging question that I had to persue: (again) what of those who know not Christ? I found an article from the Antiochian Diocese. Aside from the comment on St Gregory of Nyssa’s “mistake”, the article stilled my heart.

http://ww1.antiochian.org/content/what-about-non-orthodox-exclusive-claims-church

Finally Father, if you have any thoughts of correction, adding, subtracting or modifying, I would know them as nothing but good, well-intended, guidance. Once again, I apologize for the length of this comment.

In much gratitude,

Paula