In previous posts, the formation and renewal of Israel through Pascha and Pentecost have been discussed. Israel as a people came into being through a mixed ethnic group around a core of descendants of Jacob being marked out by the blood of the Passover lamb, delivered from Egypt through the sea, culminating in the reception of God’s covenant at Sinai with the sprinkling of blood. Subsequent generations were integrated ritually into Israel through the celebration of the Passover and Pentecost within the yearly ritual cycle. After most of Israel had been dispersed to the nations, she was resurrected with Christ at the second Pascha by the reintegration of the nations around a core of the remnant of Judah. The culmination of this renewed Israel and its assembly as the church of Christ, happens at a second Pentecost. The feast of Pentecost, before the Pentecost of Acts 2, was the annual celebration of the original giving of the Torah, God’s covenant with Israel, 50 days after the Passover. Pentecost was, within Second Temple Judaism, a feast of covenant renewal, in which the faithful would repent of their sins of the previous year and recommit to the covenant made with their fathers. Amongst diverse other realities manifested by the coming of the Holy Spirit is fulfillment of Pentecost in the granting to the restored Israel of the new covenant.

In previous posts, the formation and renewal of Israel through Pascha and Pentecost have been discussed. Israel as a people came into being through a mixed ethnic group around a core of descendants of Jacob being marked out by the blood of the Passover lamb, delivered from Egypt through the sea, culminating in the reception of God’s covenant at Sinai with the sprinkling of blood. Subsequent generations were integrated ritually into Israel through the celebration of the Passover and Pentecost within the yearly ritual cycle. After most of Israel had been dispersed to the nations, she was resurrected with Christ at the second Pascha by the reintegration of the nations around a core of the remnant of Judah. The culmination of this renewed Israel and its assembly as the church of Christ, happens at a second Pentecost. The feast of Pentecost, before the Pentecost of Acts 2, was the annual celebration of the original giving of the Torah, God’s covenant with Israel, 50 days after the Passover. Pentecost was, within Second Temple Judaism, a feast of covenant renewal, in which the faithful would repent of their sins of the previous year and recommit to the covenant made with their fathers. Amongst diverse other realities manifested by the coming of the Holy Spirit is fulfillment of Pentecost in the granting to the restored Israel of the new covenant.

That there would be a new covenant was one of the central promises of the prophets regarding the regathering of Israel as the people of God. There are two primary prophetic passages which describe the new covenant’s coming and nature. The first is Jeremiah 31 (38 in the Greek text). The second is Ezekiel 36. In both cases, the chastisement and discipline suffered by Judah is described, while at the same time the promises of redemption and regathering are also extended to the tribes of Israel who have been dissolved into the nations (Jer 31:5-6. 9, 18-20, 27; Ezek 36:1, 8, 19-22). The promise is of a regathering from all the nations and resettlement in the land (Jer 31:4-5. 8-9. 12-14, 16-17, 21-22, 27-28; Ezek 36:8-15). Finally, the promise is of a new, transformative covenant. Just as the reception of the old covenant was the climax of the birth of Israel, so also it is the culmination of Israel’s rebirth. It is therefore appropriate that at the second Pentecost there was a gathering of the remnant of Judea from the nations of the world (Acts 2:9-11).

As the people were being deported into exile under the Neo-Babylonian empire, Jeremiah prophesied that the time was coming when Yahweh, the God of Israel, would issue a new covenant to the house of Judah and the by then already vanished house of Israel (Jer 31:31/38:31). This would implicitly indicate that as the first covenant had been issued after Yahweh’s victory over the gods of Egypt and the redemption of his people (v. 32), this new and greater covenant would be proceeded by a new and greater victory. This victory is the gospel. The core description of this new covenant is that “Yahweh declares, ‘I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. And I will be their God, and they will be my people. No more will each teach his neighbor and each his brother saying, ‘Know Yahweh,’ because they will all know me, from the least of them to the greatest…for I will forgive their wickedness and no longer will I remember their sin'” (v. 33-34).

Here, already, is the first point at which the new covenant is superior to the old. The Torah was the product of Yahweh’s desire to dwell among his people. What prevented this was Israel’s sin and impurity. Because of this, man had been expelled from God’s dwelling place in the beginning (see Gen 3) and afterwards man had become increasingly corrupt. This corruption reached a pinnacle that required God to purify creation from humanity which was poisoning it with the pollution of sin through the flood (Gen 6-9). Though God declared peace thereafter with humanity, the problem of sin and pollution had not gone away. The incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ was already the divine plan for dealing with the problem of sin and corruption as well as death and the hostile spiritual powers. In the meantime, however, until that plan and that victory came to fruition, a system was required to manage sin and the resultant pollution within Israel’s camp in the desert and in the land so that Yahweh could continue to dwell in their midst in tabernacle and temple. The Torah represents this system in identifying sin and corruption and providing a means to manage it and the resultant stain upon human persons and the land itself. Israel and then Judah’s failure to follow this system, allowing instead abomination and pollution to build to a point of crisis, resulted in the departure of Yahweh from their midst, and destruction and exile. The new covenant offers forgiveness, the removal of our sins as far as the east is from the west (Ps 103:12), and complete purification from its pollution (1 John 1:9). This represents the fulfillment (in the true sense, being filled to overflowing) of the sin management system of the Torah in Christ. For this reason, in meditating upon this passage in Jeremiah, Hebrews sees the old covenant as now obsolete, by virtue of being surpassed (8:6-13).

During the exile, through the prophet Ezekiel, the promise of the new covenant that through the Torah being written on the hearts of all people, they will all come to know Yahweh. This will take place when he gathers together all Israel from ‘the nations…all the countries’ in which they have been scattered (Ezek 36:24, see also 11:16). Note that the exiles from Judah are all in one place, Babylon, such that Ezekiel can travel to them (11:24). At a literal level, the 10 tribes of the northern kingdom had vanished through intermarriage and assimilation with residents of Mesopotamia, not so far from Babylon. Yet Yahweh says that he will be regathering his people, all of Israel, from all of the far off nations within which they are scattered to reassemble them as a new people and give them this new covenant.

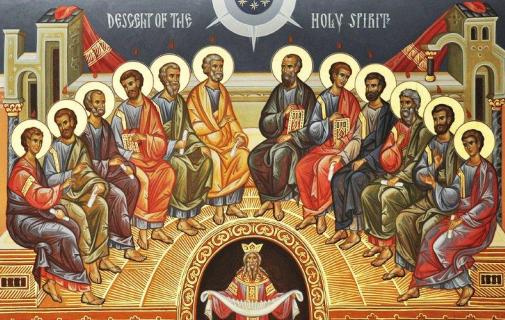

Here also is the theme of purification and cleansing. God’s people will have clean water poured over them and they will be clean (36:25). They will be cleansed from all of their wickedness (36:33). In the old covenant, the tabernacle was cleansed yearly of the accumulated taint of the peoples’ sin to allow the presence of Yahweh to continue to dwell there. The cleansing which takes place through the blood of Christ is not done only to a sanctuary but of human persons (1 John 1:7). This allows God himself to come to dwell within human persons. The Holy Spirit came upon the apostles at the second Pentecost as a result of this cleansing, and as the fulfillment of the promise of the new covenant. “I will put my Spirit within you and make you to walk in my commandments and be careful to obey my rules…you will be my people and I will be your God” (Ezek 36:27-28).

This means that the knowledge of God, knowing God rather than about him, is immediate to every human person who has received the Holy Spirit. Yahweh is not someone who must be taught about, who dwells in a (perhaps remote) temple, but rather Yahweh dwells within each of his people. When the people assemble for worship, in the power of the Spirit, Christ is in their midst. The apostolic generation was purified and set apart through St. John’s baptism and the ministry of Christ to receive the Holy Spirit at the second Pentecost and the giving of the new covenant. Subsequent generations have come to participate in the new covenant through the ritual of baptism, cleansing from sin followed by the receipt of the Holy Spirit. This covenant is renewed continuously in the Eucharist at the reception of Christ’s blood of the new covenant.

Notice that in both Jeremiah and Ezekiel, the Torah is not done away with. It is surpassed by something greater. It is filled to fullness and then to overflowing. Both prophets promise that in the new covenant, the Torah will be written on the heart by the Spirit, and that the Spirit will keep the Torah within the member of Yahweh’s people Israel. While the Torah could point to sin and proscribe means of managing it, it could not do away with sin or overcome it. St. Paul states that these latter things had to be accomplished by Christ, who does away with sin so that the Spirit can come to dwell within us and fulfill the righteous requirements of the Torah (Rom 8:3-4). The Spirit being present within us naturally brings not only repentance through our knowledge of God and his commandments, but also good fruit which blossom forth to eternal life (John 4:36). “The fruit of the spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self control. Against these things there is no law” (Gal 5:22-23).

In later prophetic literature, the blood of the first Pascha and the blood of the covenant at Sinai was referred to as the blood of Israel’s birth (cf. Ezek 16:4-7). Subsequent celebrations of the feast of Pentecost were, therefore, a sort of ‘birthday’ for God’s people Israel. As the giving of the covenant was remembered, it was a day to take stock of one’s obedience to God, and a day of repentance and recommitment. While it has become something of a commonplace to refer to the second Pentecost of Acts 2 as ‘the birthday of the church,’ some have objected that the church had already existed. It is true that the ekklesia, or assembly, of Israel existed from that day of the first Pentecost when the people assembled to be sprinkled by Moses with the blood of the covenant (Ex 24:8). However, on that particular anniversary of that assembly, Israel was reborn as what we call today the Orthodox Church. Appropriately, therefore, the kneeling prayers of Pentecost represent a time to once again take stock, to offer prayers of repentance, and to intercede for the living and the departed. Pentecost is a birthday, the anniversary of the covenant which has created God’s people Israel.

Thank you Father Stephen!

Would you address how it is that the faithful of the OT, without being physically present at the rebirth of Israel, the second Pentecost, are still included in the new covenant? I am thinking about Hebrews 11 and how it says that the righteous of the OT are those who had the faith of Abraham, ending with this:

“And all these, having obtained a good testimony through faith, did not receive the promise, God having provided something better for us, that they should not be made perfect apart from us.”

Did I just answer my own question. or is there more?

I think you have sort of answered your own question. The Torah, the old covenant, didn’t solve the problems of the evil spiritual powers, sin, and death. It only managed them until Christ came and dealt with them. This is what lies behind Hebrews and also the imagery of the harrowing of Hades on holy Saturday. It’s through the Pascha and Pentecost of Christ that the saints of the old covenant receive the promises in which they had steadfastly believed.

Very good Father. Thank you.

Father,

Is the valley of the corpses and ash mentioned in Jer 31:40 the valley of Hinnom?

If so, what impact does this have?

It is. But the reference doesn’t seem to be, in context, related to the eschatological concept of Gehenna. As the exile approaches, for Jeremiah, the valley of Hinton is sort of ‘Exhibit A’ of the people’s apostasy and wickedness. So the reference here is that when the new covenant comes to fruition (pun am ntended), even this horrible, wicked place will be a place holy to Yahweh. And that last part doesn’t just mean it will be neutral. It means that the whole creation will be a temple because God’s presence will fill it all.