Though it is the name used for the people of God in both Old and New Testaments, ‘Israel’ as the name for God’s people had only a limited historical span. As a united people freed from Egypt, depending on one’s dating of the Exodus, Israel existed for between 300 and 500 years. Only the last century of this period represented an actual kingdom under a human king. Following the fracturing of the tribes at the end of Solomon’s reign, it was the northern ten tribes that existed under the name ‘Israel’ for very roughly 200 years before its complete destruction at the hands of the Assyrian Empire. Even during those two centuries, the northern kingdom was better known as ‘Ephraimite’ or ‘the House of Omri’ to most of its neighbors, rather than as ‘Israel’. Nevertheless, the promises of restoration made by the prophets all concern the restoration not of Judah only, but of Israel. When the New Testament speaks of the salvation of God’s people, it is not Judea or the Judeans who are addressed, but rather Israel (cf. Matt 2:6, 20, 21; 8:10; 9:33; 10:6, 23; 15:24, 31; 19:28; 27:42; Acts 5:31; Rom 11:26; Heb 8:8-10). This post will describe what Israel was in the old covenant, how it came into being, and its fate. Next week’s post will describe how Israel has been renewed and reconstituted within the new covenant, as understood by St. Paul and other New Testament writers.

Though it is the name used for the people of God in both Old and New Testaments, ‘Israel’ as the name for God’s people had only a limited historical span. As a united people freed from Egypt, depending on one’s dating of the Exodus, Israel existed for between 300 and 500 years. Only the last century of this period represented an actual kingdom under a human king. Following the fracturing of the tribes at the end of Solomon’s reign, it was the northern ten tribes that existed under the name ‘Israel’ for very roughly 200 years before its complete destruction at the hands of the Assyrian Empire. Even during those two centuries, the northern kingdom was better known as ‘Ephraimite’ or ‘the House of Omri’ to most of its neighbors, rather than as ‘Israel’. Nevertheless, the promises of restoration made by the prophets all concern the restoration not of Judah only, but of Israel. When the New Testament speaks of the salvation of God’s people, it is not Judea or the Judeans who are addressed, but rather Israel (cf. Matt 2:6, 20, 21; 8:10; 9:33; 10:6, 23; 15:24, 31; 19:28; 27:42; Acts 5:31; Rom 11:26; Heb 8:8-10). This post will describe what Israel was in the old covenant, how it came into being, and its fate. Next week’s post will describe how Israel has been renewed and reconstituted within the new covenant, as understood by St. Paul and other New Testament writers.

At the tower of Babel, God dispersed the nations and disinherited them, assigning their governance to angelic beings who later became corrupt and who those nations came to worship as gods (Deut 32: 8, 17). God did not then choose one of the existing nations to purify and make his own, electing Israel from among the abandoned nations. Israel is nowhere to be found in the list of the 70 nations of the world in Genesis 10. Rather, God creates a new nation for himself. creating a people who, before his creative action, were not (Deut 32:6, 10;). When God reveals his name to Moses, ‘Yahweh’, it is in this context. Though it is impossible to determine with absolute certainty, the name ‘Yahweh’ appears to be the Hebrew verb ‘to be’ in the Hiphil binyan, meaning ‘he who causes to be’. The God of Israel, therefore, is the one who creates, the one who causes things to be which previously were not. Yahweh, the God of Israel, begins this process with Abraham, but Abraham’s significance extends beyond his status of progenitor of Israel. The promise to Abraham are that many nations will come from him, and many do, such as Edom, Moab, Ammon, the Ishmaelites, and others from his family descent in addition to Israel. The further promise made to him is that all of the nations of the world will bless themselves in him.

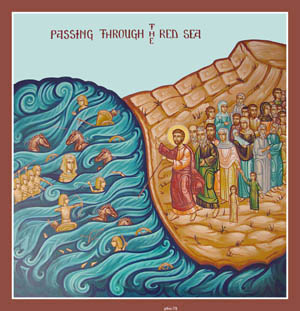

In the understanding of the Hebrew scriptures, it is at the Exodus that Israel as a nation is born (cf. Hos 11:1; Ex 4:22; Eze 16:4-7). Specifically it is in the cycle of events from the Passover to the reception of the Torah at Sinai, from Pascha to Pentecost, that Israel came into being as a people and a nation. While the Torah would later proscribe intermarriage between the people of Israel and their neighbors, Semitic or otherwise, the patriarchal narratives do not consistently apply such a prohibition. While it is important to Abraham and Sarah that Isaac take a wife from ‘their own people’, this refers to a Mesopotamian rather than a Canaanite (Gen 24:2-4), Joseph takes for his wife an Egyptian woman, the daughter of a pagan priest, with no opprobrium in the Biblical text (Gen 41:45, 50; 46:20). During the four centuries that the family and descendants of Jacob spent in the Nile delta region of Egypt, they lived among other Semitic migrant peoples (called ‘Asiatics’ by the Egyptians) and native Egyptians and there is every indication that they intermarried (Ex 11:2). Some significant portion of this family became a part of Egyptian culture and religion (Eze 23:19).

When Moses is sent back into Egypt to redeem God’s people from slavery, he begins with the faithful remnant of the household of Jacob, whose name had been changed to Israel. As Yahweh strikes Egypt and its gods with plagues, the region where these faithful Israelites dwell is spared their effects (Ex 8:22-23; 9:4-6, 25-26; 10:22-23). This also meant that the non-Israelite neighbors and faithless Israelites dwelling in the same region were also spared. When the time comes, however, for the birth of Israel to begin with the final plague upon the firstborn, those redeemed, purchased, by Yahweh out of slavery are not defined by the geographical region in which they dwell or by their ethnic descent. Rather, they are defined by their faithfulness to their God, and that faithfulness is expressed in ritual. The ritual of the Passover, including its celebration in perpetuity, is described in detail before the Passover actually occurs (Ex 12:3-20). The initial shape of the nation and people of Israel, therefore, is defined by those marked out by the blood of the Passover lamb. This marker is not only initial, but ongoing, as the celebration of the Passover allows future generations to participate in this event and thereby become members of Yahweh’s redeemed people. Importantly, when this people left Egypt, it included an ethnically mixed group of Egyptians and other Semitic migrants (Ex 12:38). This group is not mentioned again in the Torah as a distinct class because these families are integrated into the nation and people of Israel and become some of its founding members.

That this occurred and how is best exemplified by the most prominent of these people not descended from Israel and yet founding Israelites, Caleb. Of all of the generation which came out of Egypt, only two men, Joshua and Caleb, entered into and took possession of the promised land (Numbers 13:26-14:24). All the rest, including Moses himself, died in the wilderness as a result of various episodes of faithlessness. Caleb becomes one of the spies sent to search out the land of Canaan because he is a chief of the tribe of Judah (Num 13:6). Caleb is, however, the son of Jephunneh, and Jephunneh is repeatedly identified as being a Kenizzite (Num 32:12; Josh 14:6, 14). The Kenizzites were a Canaanite people who already lived in Canaan at the time that Abraham had arrived there (Gen 15:19). Caleb and his family were among the many Semitic migrants to Egypt during this period, and yet through his faithfulness to Yahweh and his participation in the events from Passover to Pentecost, he became a part of the tribe of Judah, even one of its chief men, and an inheritor of the promises to Abraham (Josh 14:13-14; 21:43-45).

After the people’s deliverance through the sea, they arrive at Sinai, which becomes the Mountain of Assembly, the mountain of God on which his divine council convenes. Moses, Aaron and his sons, and the seventy elders from the tribes of Israel are invited partway up the mountain to see Yahweh, though only Moses himself goes and remains in the presence of the God of Israel for 40 days (Ex 24:1-2, 9-12). Here Yahweh issues to the newborn nation of Israel a covenant, berith in Hebrew. This covenant follows the form of contemporary suzerainty treaties, which were issued by a conquering king to his new vassals to identify himself, describe what he had done for them, and their responsibilities in return to maintain peaceful and prosperous relations with their king. Gathered at the base of the mountain, Israel agrees heartily with the covenant given them (Ex 24:7). Connecting this founding moment of the nation to the marking out of the people at the Passover, this is ritually sealed when Moses sprinkles the people with sacrificial blood, the blood of the covenant (Ex 24:8). This event also became an annual feast to allow for the ritual participation of future generations as the feast of Pentecost.

Yahweh, the God of Israel, kept his promises to the people by settling them in the land in their allotments. They lived for some centuries as a coalition of tribes before becoming a monarchy under Saul, David, and Solomon. In reality, this period saw not so much a united kingdom but the southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin able to project their rules over an increasing area of the northern tribal lands and peoples. This collapsed following the death of Solomon, with Solomon’s son Rehoboam retaining kingship over only the southern territories of Judah and Benjamin. Jeroboam the son of Nebat, one of Solomon’s officials, rebelled and formed a new northern monarchy which took for itself the name Israel. Jeroboam himself set up a new religious system centering around idolatrous shrines at Bethel and Dan in the north. Later generations would seek to syncretize this idolatrous form of Yahweh worship with the Baal worship of neighboring lands to the north. Omri, the founder of a later northern dynasty, would purchase a hill and build the city of Samaria to serve as a northern capitol within the territory of Ephraim, the largest and most prominent tribe of the north. At no point in its relatively brief history was this northern kingdom faithful to their God or righteous in their ways. This resulted in the complete destruction of the 10 northern tribes barely 200 years after the founding of their independent kingdom (2 Kgs/4 Kgdms 18:9-12). The Assyrian empire as a standard policy, in order to prevent future rebellion of conquered peoples, deported those peoples from their native lands to other parts of the empire and brings peoples from those other regions to the newly conquered lands. The foreigners brought in to the region around Samaria interbred with the remaining Israelites to produce the Samaritan peoples. The people of Israel deported to Assyria, after several generations of intermarriage and assimilation, disappear into the larger Gentile population and cease to exist as a separate people.

The southern kingdom of Judah survived the Assyrians and though she went into Babylonian exile, a remnant was allowed to return after 70 years establishing the province of Judea. The promises of restoration in the latter days, however, made by Yahweh the God of Israel through his prophets, are made not to Judea or the Judeans (the name translated ‘Jews’ in most English translations of the Bible), but rather to Israel. These two terms are not synonymous in the context of these promises, which clearly and specifically reference the restoration of the northern tribes. Jeremiah, for example, prophesying at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem, 150 years after the beginning of the Assyrian deportations through which these tribes had vanished, speaks of the restoration of God’s people saying, “Yahweh appeared to him from far off saying, “I have loved you with an eternal love. Therefore I have drawn you with lovingkindness. I will build you again and you will be rebuilt, virgin of Israel. You will pick up your instruments again and go out with the dances of the revelers. You will plant vineyards again on the hills of Samaria. The planters will plant them and will enjoy them. Because there will be a day when watchmen on the hills of Ephraim cry out, ‘Arise, and let us go up to Zion, to Yahweh our God'” (Jer 31:3-6; 38:3-6 in the Greek). In Jeremiah’s vision, not only will the northern tribes, including their capitol, be restored, but they will worship their God in truth at Jerusalem which had never occurred in the previous history. Jeremiah says later, “‘In those days and at that time,’ declares Yahweh, “the sons of Israel will come. They and the sons of Judah as well will go, weeping as they go, and it will be Yahweh their God whom they seek. They will ask the way to Zion, setting their faces in that direction. They will come so that they might join themselves to Yahweh in an everlasting covenant that will not be forgotten'” (Jer 50:4-5; 27:4-5 in the Greek).

Ezekiel, prophesying in captivity in Babylon is told, “The Word of Yahweh came to me, saying, ‘Son of man, take a stick and write on it, ‘For Judah, and the people of Israel associated with him’. And take another stick and write on it, ‘For Joseph, the stick of Ephraim, and all the house of Israel associated with him.’ Join them one to another into one stick, that they may become one in your hand. And when your people say to you, ‘Will you not tell us what you mean by these?’ say to them, ‘Thus says the Lord God: See, I am about to take the stick of Joseph that is in the hand of Ephraim and the tribes of Israel associated with him. And I will join with it the stick of Judah, and make them one stick, that they may be one in my hand.’ When the sticks on which you write are in your hand before their eyes, then say to them, ‘Thus says the Lord God: See, I will take the people of Israel from the nations among which they have gone, and will gather them from all around, and bring them to their own land. And I will make them one nation in the land, on the mountains of Israel. And one king shall be king over them all, and they will no longer be two nations and no longer be divided into two kingdoms. They will not defile themselves anymore with their idols and their abomination or with any of their transgressions. But I will save them from all the transgressions in which they have sinned, and will purify them, and they will be my people, and I will be their God. My servant David shall be king over them and they will all have one shepherd. They will walk in my rules and be careful to obey my statutes'” (Eze 37:15-24).

In the vision of the Hebrew prophets, at the coming of the Messianic king, Israel would be reconstituted. This would require not only the redemption of the remnant of Judea, but also the reconstitution of all of Israel, including the northern tribes who had been dispersed and ceased to exist among the Gentiles. To do this would require a new act of creation at the hand of the God of Israel. Or, as Ezekiel 37:1-14 would have it, it would require a resurrection.

Father Stephen,

I stand amazed at your teachings! I am ever so grateful for the subject of this and the upcoming post. I only read as far as the 2nd sentence, where Israel as a united people existed for 300-500 years and it was there I knew that everything I was taught in the past about Israel and the Jewish people was about to be turned upside-down and properly redefined…or should I say, ‘reconstructed’. Because the impression given was that Israel, for all intents and purposes, always existed. It was from the day God told Abraham that the land as far as his eyes could see would be his (Gen 13: 15-17). Even though they were dispersed and defeated by several kingdoms…Israel always existed. It was an indelible impression.

My takeaway, in a nutshell, is that when we read “Israel” in the OT we should read it as a shadow of, or as hidden, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

Thank you for this thorough and well informed teaching. I am very much looking forward to part two.

Sorry, one more thing…to conclude the article so appropriately with reference to the Valley of Dry Bones, to me one of the most phenomenal verses in scripture, was, how do you say, the icing on the cake. Thanks again….