As a bridge between the discussion of Christ in St. Paul’s epistles and Christ in the General Epistles, it is important to discuss a second factor in St. Paul’s understanding of Christ as God. This concerns the oft-neglected area of St. Paul’s own personal practices of prayer and piety, and how this relates to both his vision of the risen Christ on the road to Damascus, in his call to be an apostle, and to his own direct knowledge of Christ as God. While the previous post discussed St. Paul’s identification of the second hypostasis of Israel’s God as the person of Jesus Christ based on Second Temple Jewish tradition, this one will focus on the epistemological issue of how St. Paul first made that identification, and how his practice of prayer, transformed from its Jewish foundation, became the basis for later Christian mystical practice. The apostolic faith, as presented in the New Testament, is based upon an apostolic vision, a vision in which later generations of Christians, particularly ascetics, would seek to share.

As a bridge between the discussion of Christ in St. Paul’s epistles and Christ in the General Epistles, it is important to discuss a second factor in St. Paul’s understanding of Christ as God. This concerns the oft-neglected area of St. Paul’s own personal practices of prayer and piety, and how this relates to both his vision of the risen Christ on the road to Damascus, in his call to be an apostle, and to his own direct knowledge of Christ as God. While the previous post discussed St. Paul’s identification of the second hypostasis of Israel’s God as the person of Jesus Christ based on Second Temple Jewish tradition, this one will focus on the epistemological issue of how St. Paul first made that identification, and how his practice of prayer, transformed from its Jewish foundation, became the basis for later Christian mystical practice. The apostolic faith, as presented in the New Testament, is based upon an apostolic vision, a vision in which later generations of Christians, particularly ascetics, would seek to share.

St. Paul lived during the formative stages of what would later be called Merkabah mysticism within the Second Temple Jewish world. This form of mystical practice represents yet another element of the religious world of first century Judaism which would later be pruned away from the Rabbinic Jewish tradition, and survive only within Christianity. The word Merkabah is the Hebrew word for ‘chariot’. In this context, it refers specifically to Yahweh, the God of Israel’s throne chariot as seen in the vision of Ezekiel recorded in Ezekiel 1. This chariot was flown about by four living creatures with the faces of an ox, a lion, an eagle, and a human. As in the days of Ezekiel the temple had been destroyed, rather than his vision focusing upon the God of Israel enthroned with the altar as his footstool (as in Isaiah 6), Ezekiel sees the divine throne in the heaven, from which Yahweh governs all of the creation. After the return from exile, in Second Temple Judaism, this vision was taken to be paradigmatic, as a vision of the reality of Israel’s God in so far as a human person could experience it without losing their life.

Merkabah mysticism, then, began with exposition of this vision in the context of Ezekiel, and meditation upon it, with the goal of receiving the same, or a similar vision. Most of those who practiced this form of mysticism admitted that they had never received the vision themselves, though some did. Through further accounts of such visions, some recorded in apocalyptic literature of the Second Temple period, a common grammar to describe these visionary experiences began to develop. The language developed of a series of heavens, ultimately seven in number, through which a series of ascents took place. Within these visions, angelic beings would be encountered, and communications with them would take place. Ultimately, the highest and purest form of these visionary experiences would be to behold the chariot-throne of Israel’s God, upon which would be seated either the Glory of God, or the Angel of the Lord figure. These mystical ascents took place through practices of contemplative prayer, generally focused upon the repetition of scriptural texts, most often the shema (‘Hear, O Israel, Yahweh our God, Yahweh is one’).

There are several clear indicators in St. Paul’s letters that he was intimately familiar with this mystical practice. For example, St. Paul refers to speaking in the tongues of angels (1 Cor 13:1). The most important text in this regard, however, is 2 Corinthians 12:1-6. Though St. Paul frames the account of this visionary experience as the experience of another man, there is a broad agreement among both the Fathers and contemporary scholars that St. Paul is describing his own experience, as alluded to in verse 6. In describing this visionary experience, he utilizes language directly parallel to that found in Merkabah sources. He speaks of the ‘third heaven’ (v. 2) and thence into paradise (v. 3) describing a series of ascents. He likewise speaks of having heard utterances that cannot be repeated from angelic beings (v. 4).

Accepting, then, that St. Paul was a participant in this tradition of prayer, new light is shed upon his vision in Acts 9. It is very clear from the language used in Acts 9, and regarding this vision by St. Paul in other writings, that this was a prophetic vision culminating in a prophetic call (as discussed here). St. Paul’s journey from Jerusalem to Damascus would have taken several days on horseback. It is reasonable to believe that on such a long journey, St. Paul would have spent much of his time in prayer and mediation, particularly at the hour of prayer at which his vision took place. This means that when his vision occurred on that road, as suddenly as it did, knocking him from his horse, this vision lay within his realm of interpretation. Within his spiritual practice, such a vision would have been seen as a gift bestowed upon only a few who were blessed to share the experience of Ezekiel and the other prophets. However, when St. Paul receives his vision, it is not an angelic figure which he sees upon the throne or divine glory, but Jesus Christ, seated on the throne-chariot of Yahweh. St. Paul’s vision on the road to Damascus is not just a vision which informs him that Jesus is the Messiah, it also powerfully showed him that Jesus Christ is God. It is on this basis that St. Paul can proceed in his epistles to speak of Jesus Christ as the incarnate second hypostasis of the God of Israel.

Further, St. Paul bases his claim to being an apostle upon this vision. It is often shorthanded that the apostles were those who had personally encountered or seen the risen Christ. This definition is not sufficient however. At one point, more than 500 people beheld the risen Christ before his ascension into heaven (1 Cor 15:6), and yet no one numbers the apostles above 500. Rather, apostolic authority is founded in having received a particular vision of Christ, of Jesus Christ in his uncreated glory, which three of the apostles had received on Mt. Tabor, all of them in witnessing Christ’s death and resurrection, and finally St. Paul on the road to Damascus. This is the experience of Christ which the apostles themselves cite. “That which was in the beginning, that which we have heard, that which we have seen with our eyes, that which we have looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life, the life which was made manifest, and we have seen it, and testify to it and proclaim to you the life which is eternal” (1 John 1-2). “For we did not follow cleverly imagined stories when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty. For when he received honor and glory from God the Father, and the voice was carried to him by the majestic glory, ‘This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased,’ we ourselves heard this very voice carried from heaven, for we were with him on the holy mountain” (2 Peter 1:16-18). Just as St. Peter had, St. Paul saw the light of God’s glory, and heard a voice from heaven.

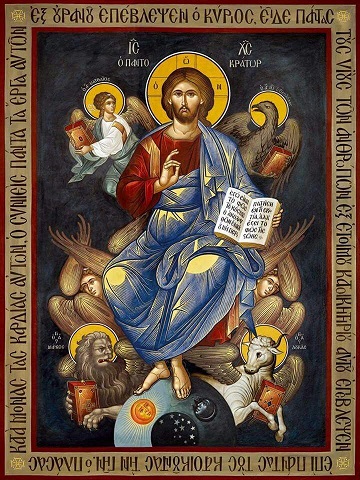

From apostolic times, Christ’s ascension into heaven and enthronement was understood within the context of the heavenly ascents and the throne-chariot of God from already existing Second Temple Jewish religion and mystical practice. It is for this reason that when Christ is presented within the Orthodox iconographic tradition enthroned, it is upon the four living creatures of Ezekiel’s vision. These icons present to us a visual means of meditation parallel to the earlier textual meditation upon Ezekiel’s vision in written form. The God who sat enthroned in the visions of the Old Testament has made himself known through descending in the incarnation, before ascending again to his former glory. Rather than repudiating mystical practice, the earliest Christians, as exemplified by St. Paul, continued to pursue contemplative prayer, which for some culminated in the vision of Christ in his uncreated glory. This tradition, repudiated in the Talmud, has continued in Orthodox Christianity, blossoming into what would later become known as hesychasm.

Thank you Father Stephen. Very interesting, especially the application of Merkabah mysticism to St. Paul’s visions. Also took the liberty to read more about it online. There is one particular website that has links to numerous articles: Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism. Lots to sift through. If you would, I’d like to know your thoughts about it. Thanks again.

I’m thinking you’re referring to the Marquette site. Which is really a treasure trove of good scholarship on this topic if you, or anyone else, is interested in further reading. Its skewed a bit toward Rabbinic over earlier sources, but its a great starting point.

Yes Father, that is the site. I’m glad you recommend it. Thank you!

I just listened to your commentary podcast on Romans 1 and was astounded that St Paul was likely reciting the Shema when we received a vision of God on the Throne, and it is revealed Christ is God! I came here to see if there were additional references and I see in the earlier comments (thanks Paula) about a site; are there any others you’d recommend, Father?

reading your book loving it, this is my first rabbit trail and I am ony a few pages in.