By Dr. Lewis Shaw

From Window Quarterly 2, 3 (1991); ACRAG c. 1991. (Source)

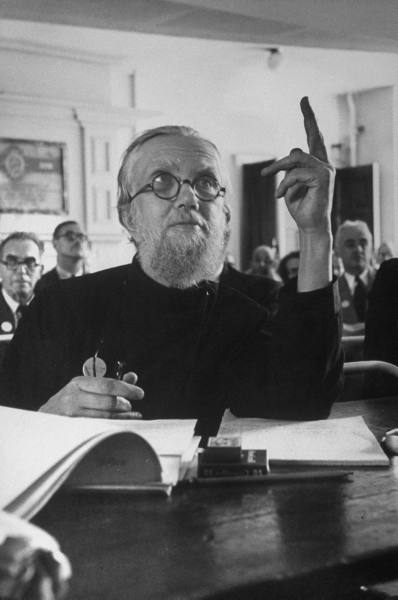

Editors’ note [from Window Quarterly]: George Florovsky (1892-1979) is one of the most eminent Russian theologians of this century. The son of a Russian priest, he graduated in arts at Odessa University (1916), subsequently lecturing there in philosophy (1919-20). Leaving Russia in 1920, he went first to Sofia and then to Prague, where he was made lecturer in the faculty of law (1922-26). In 1926 he became Professor of Patristics at the Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris, and later Professor of Dogmatics. He was ordained priest in 1932. Moving to the U.S.A in 1948, he became successively Professor and Dean at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, New York (1948-55). Professor of Eastern Church History at Harvard Divinity School (1956-64), and Visiting Professor at Princeton University. He has written extensively on the Greek Fathers (mainly in Russian), urging the necessity for a “neo-patristic synthesis.” He has played a leading part in the Ecumenical Movement, starting in the 1930’s and has served regularly as delegate at assemblies of the Faith and Order Commission of the World Council of Churches. His Collected Works have been published in ten volumes.

A viable and faithful model of Orthodox ecclesiology is that provided by the main representative of the Traditionalist current of the “Paris School” of Russian theology, Georges Florovsky (1892-1979). Florovsky’s theological pilgrimage was not one of creative speculation, but of a discovery of the “code”[1. Cf. The Byzantine Fathers of the Sixth to Eighth Century, CW IX, p. 256, where Florovsky construes the thinking of St. John of Damascus as a “code.”] underlying the “ecclesial mind” expressed in the Church’s literary classics, iconography and liturgy. Florovsky presented the theological content of his “neo-patristic” synthesis within the all-encompassing ecclesial framework which he regarded as the necessary vantage point for all theology.

Florovsky’s ecclesiology infused his whole approach to theological discourse. His ecclesiology was one of sustained metaphor and image, rather than one which concentrated on delineating the locus or the matrix of the Church’s authority.[2. Certainly Florovsky gave consideration to the issue of ecclesial authority; but he did not emphasize it. His thinking about authority and its relation to other themes may be summarized as follows. Tradition is the property of the whole assembly of baptized persons, the Body of Christ; but the hierarchy has an especial potestas magisterii and obligation to speak for the Church (nevertheless, it should perhaps be noted here that Florovsky paid little written attention to a theology of Holy Orders). The episcopus in ecclesia is the apostolic center of catholicity. It is his duty to witness to Catholic Faith, never to propound personal opinion or theologoumena; episcopal authority is not ex sese. Neither does it rest on the Church’s consensus–it is from Christ. The “reception” of dogma by the Church raises problems as dogmatic truth is never to be settled by majority vote. The basic unity of “life in Tradition,” resting on the twin pillars of kerygma and dogma, continues as it is “sensed” by the “ecclesial mind.” It is this life, constituted in the sacraments, which guarantees dogmatic truth. There can be no ‘external authority’ in the Church, no power whereby dogma may be imposed, as Florovsky sees it; authority is not the source of spiritual life. In the Church the community of “sobornost” and the simultaneous image of both Christ and the Trinity–the division in the “natural consciousness” between the claims of freedom and of authority–disappear in the “concrete union” of love.] He stopped short of a definition of the Church, or even of acknowledging the need for such a definition. Indicatively, he wrote: “The Fathers did not care so much for the doctrine of the Church precisely because the glorious reality was open to their spiritual vision. One does not define what is self-evident.”[3. “The Church: Her Nature and Task,” CW I, p. 57.] Despite his refusal to systematize, the Christological theme informed his understanding of the Church and therefore the significance of the Church in the theological task. Florovsky appropriated St. Augustine’s image of the Church as the Whole Christ, Head and Body [source text reads “Whole Church, Head and Body,” which is an error – ed.]; as such it mirrors the two natures of the Incarnate Word in its theanthropic union. As the mystery of Christ is discernible only from within His Body, so that same Christological reality reflects back upon the Church, its being, and its purpose. Christological theandrism for Florovsky provides the key to a correct understanding of the mystery of the Church, the only positive ground of research for the extended pedagogical and catechetical exercise of theology.[4. ibid., p. 68.]

Florovsky schematized patristic thought as a fusion of Greek cosmology with Israel’s continuing confession of revelation. He was not, however, like T. F. Torrance and others, interested in quantum mechanics, or a dialogue between theoretical physics and theology. He was concerned with the dynamic of creation, inasmuch as it pertained to the exercise of freedom in salvation history, the key to which is eschatology. The matrices of patristic categories, for Florovsky, were Origen’s philological and textual interpretations of Scripture, and the salvation history read from it. Florovsky’s “code” did not accommodate contradiction. The importance of St. Maximus the Confessor and Leontius of Byzantium, for example, was not in a surpassing originality, but in their theological gifts for sensing the pneumatic instinct of the Church–their ability to hear and discern the unitive voice of the Holy Spirit in Tradition. In this Florovsky seemed to set as his pattern St. John of Damascus, the synthesizer par excellence of the Cappadocians, Leontius, and St.Maximus. Of the Damascene Florovsky approvingly wrote in The Byzantine Fathers of the Sixth to Eighth Century:

As a theologian St. John of Damascus was a collector of patristic materials. In the Fathers he saw ‘God-inspired’ teachers and ‘God-bearing’ pastors. There can be no contradiction among them: ‘a father does not fight against the fathers, for all of them were communicants of a single Holy Spirit.’ St. John of Damascus collected not the personal opinions of the fathers but precisely patristic tradition. ‘An individual opinion is not a law for the Church,’ he writes, and then he repeats St. Gregory of Nazianzus: ‘one swallow does not a summer make. ‘And one opinion cannot overthrow Church tradition from one end of the earth to the other.'[5. The Byzantine Fathers of the Sixth to Eighth Century, CW IX, p. 257.]

Florovsky’s own view that the patristic tradition was a synthesis without contradiction raises some problems which are beyond the scope of this article.

It was the rediscovery of a coherent vision of history that Florovsky encouraged, not an initiative toward fresh speculative theologoumena [opinion]; the attempt at such rediscovery is foundational to his neo-patristic scheme. Inasmuch as it is the Israel of God, the Church testifies continually in its inheritance of faith and its path of pilgrimage that God is none other than the Creator of the universe and Lord of history, the God of Abraham and Father of Jesus Christ, Who yet hovers over His creation as Spirit. For Florovsky the primary meaning of faith is trust, the sense of God and His will, and the working-out of His intention in history, where He has acted upon, and through, His people, the Church. Florovsky believed that the Triune confession–the testimony and knowledge of the Church as predicated upon its experience of the Covenant Holy One of Israel as God’s compassion in Jesus Christ and His Presence in the Spirit–given a basis for adequate voice and formulation in the language of the Church’s Tradition, is central to the Church’s discussion of God’s relation to the world. God has identified Himself to the Church as Triune. For Florovsky catholicity, askesis (self-denial) and the Triune identity, or Trinity, are linked in an ecclesial exposition of personality, self, and ego, all key ingredients in a radical, ecclesial modification of human self-consciousness. When the Church speaks of God, it tells of the Father Who created it and gave it life, the Son Who redeemed it, and the Spirit Who empowers it. God and the Church face and hear each other as a multiplicity of persons, by definition distinct, bound together in the loving communion of Redeemer and redeemed. Christians experience the Personal reality of God in the activity of the Trinity.

The Church, which Florovsky sees as the completion of the Incarnation, is therefore the primary reference point of anthropology. The image of God constitutes the esse of the human being; it is to live in God, and to have God in our hearts. Humanity finds its fullness and completedness in Christ and His Body. This is the clue to the meaning of catholicity. Catholicity is the very affirmation of self, expressed in redeemed character; in the fullness of the communion of saints, the clarity of God’s will–the “catholic transfiguration of personality”–is accomplished. In catholicity, the concrete union of love, the consciousness of contradiction–that which would distort the Church’s unity–disappears. The Church’s life, however, is inevitably fraught with conflict. The unity of the world has been compromised; God’s deification of creation is the work of relentless warfare with the insidious attraction of nothingness, that is, evil. Evil enslaves humanity and perverts its vocation to divine sonship. Humankind is awakened from its self-delusion and narcissistic obsession with itself by the presence of God, Who urges it toward Christ and His invitation to the active partnership of creative redemption. That partnership begins with fidelity to covenant as faith, trust in Who Jesus is in His own Person, the New Covenant. God, history’s central actor, “planned” the Incarnation of Christ before time began. All God’s mighty acts are election toward the purpose of Incarnation, the intended blessing and fulfillment of creation. The starting point of the Christian faith is for Florovsky “the acknowledgment of certain actual events, in which God has acted, sovereignly and decisively, for man’s salvation, precisely in these last days.”[6. ‘The Predicament of the Christian Historian,’ CW IX, p. 58.]

Man, according to Florovsky, is the only creature in the cosmic system capable of free action; God has “legislated” his self-determination. Man has a desire for God, and for knowledge of Him. The culmination of the strenuous effort of mystical ascent–for Florovsky the ascetical ‘ordeal’–is

represented in the person of Mary, who, in her free, affirmative, and active response to the Spirit’s invitation of grace, achieved the sense of God. The Annunciation, Conception, and Incarnation not only show humanity deified; these events also manifested God’s longing and intention to become human. Florovsky stressed Christ’s assumption of human nature, and the Incarnation, as the ultimate initiatives of grace and healing on God’s part. According to Florovsky the distinction and relationship between Christ’s human and divine natures–defined by Chalcedon–was in fact necessary for the Incarnation, and is the norm governing the totality of human life. The Truth–not an abstract idea, but a Person–was given Word by becoming man. “The Bible,” Florovsky wrote, “can never be, as it were, ‘algebraized.’ Names can never be replaced by symbols. There was a dealing of the Personal God with human persons. And this dealing culminated in the Person of Christ Jesus…”[7. ibid., p. 59] Jesus was His own Scripture. Love is the force motivating salvation, and its purpose and display are the Cross, sacrament of love par excellence. It is this sacrament and sacrifice which are the divine call and vocation heard in the Church, the unity of all believers in catholicity and grace.

Through the Church, the home of the synthetic code, Christ summons humankind by grace into the path of eschatological tension and self-denial. The disciple is “ingodded” through the sacraments, and as a consequence, is led to understand the fullness of Christ’s mind in His Church, in the continuity of the Spirit’s gracious help. Florovsky’s consideration of ecclesial anthropology leads through his concept of catholicity to an assertion of the sacramental vocation and transformation of humanity. The path of eschatological dynamism is precisely that of the Church’s sacramental life, a life infusing and supporting the community of faith during her journey between the beginning and end of time.

Florovsky, following the lead of St. Cyril of Jerusalem,[8. ‘The Catholicity of the Church,” CW I, p. 41.] saw the profoundest expression of the Church’s catholicity in her sacramental assemblies of washing and feeding, the mysterion tis synaxeos (mystery of gathering together). Sacramental assembly (synaxis) is the identity of the Church’s experience, the gathering where her royal priesthood is discharged, the purpose and finishing of life in Christ. This is the communion of the risen High Priest, the fellowship of co-mediation celebrated in to teleutaion mysterion, the ultimate sacrament.[9. ‘The ‘Immortality’ of the Soul,” CW III, p. 237.] It is in the final mystery of communion shared with the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world,[10. “Redemption,” CW III, p. 100.] that the Church fully expresses her catholicity, a vision of the mystical conquest of time and the transformation of history. The Cross fuses death and birth, baptism and Eucharist; on Golgotha the Holy Service of Eucharist is celebrated by the Incarnate Lord in a baptism of blood and sacrifice of human nature.[11. ibid., pp. 132-133.] This is the communion of co-mediation formed on the Cross by the High Priest of the good things to come.[12. ibid., pp. 131.]

Florovsky’s sacramental theology effectively blended the imageries of Scripture and the patristic inheritance.[13. ibid., pp. 131-159. Florovsky’s sacramental and anthropological language remarkably like the sacramental and anthropological] Sacraments constitute the Church, revealing her catholicity in a fellowship of God’s own possession, a communion in holy things presided over by the now and future High Priest, the Church’s Bridegroom Who plights His troth of Eternal Life to His Beloved.[14. ??] Since the world was created in view of Christ and His Body, the Church has a cosmic import; all creation is called to it, and so as it prays and serves the Liturgy, it sanctifies the fruits of creation in “the bath of salvation, the heavenly Bread, and the Cup of Life.” The Church is the likeness of man, the pinnacle and glory of creation. Resurrection is creation history’s point of convergence, and it already bears fruit in the Church’s ontological conversion of humankind, expressed and sealed palpably in the sacraments. A kind of macro-humanity, the Church takes shape and grows until it accommodates all who are called and foreordained. In Florovsky’s view the sacred history of God’s mighty acts is still continued in the Israel of God, where “salvation is not only accounted or proclaimed…but precisely enacted [viz. the sacraments].”[15. ??]

In Florovsky’s understanding “the ecclesial mind,” or “sense,” expresses itself as the divine conversion of prayer: a habit and attitude of personal relation between believers and God,

in the Church. This habit forms, in the Church’s renewing deposit of the charisma veritatis (grace of truth), a “sacramental community” enchristing and anointing all who bear Jesus’ title as a name, Christians, in history, for all time. Grace is hypostasized and realized in the visible words, the “logoi,” of the sacraments, God’s very own, sealed energies. The Church is God’s teleological vision and command, and as God eternally contemplated the image of the world, so with good enjoyment does He intend the transformation of image into the likeness of new life in grace in His Church. In this mystery of sacramental catholicity, the Church expresses her vision of the mystical conquest of time and the transformation of history. Hearing the Word of God in the Church’s sacramental conversation, we are raised into the hope and pilgrimage of Pentecost.

[O&H editor’s note: The source text of the footnotes is garbled and cut off here, so even though footnotes 14 and 15 are marked, we don’t have the text of the notes. We have also cleaned up the text in places and regularized the Latinization of Greek words throughout.]

Abbreviations: “CW (I-X)” refers to The Collected Works of Georges Florovsky (Vaduz, Liechtenstein, l987), Volumes I-X, ed. R.S. Haugh.

Thank you for this article!

I especially like this portion: “Florovsky’s ‘code’ did not accommodate contradiction. The importance of St. Maximus the Confessor and Leontius of Byzantium, for example, was not in a surpassing originality, but in their theological gifts for sensing the pneumatic instinct of the Church–their ability to hear and discern the unitive voice of the Holy Spirit in Tradition. In this Florovsky seemed to set as his pattern St. John of Damascus, the synthesizer par excellence of the Cappadocians, Leontius, and St.Maximus. Of the Damascene Florovsky approvingly wrote in The Byzantine Fathers of the Sixth to Eighth Century:

As a theologian St. John of Damascus was a collector of patristic materials. In the Fathers he saw ‘God-inspired’ teachers and ‘God-bearing’ pastors. There can be no contradiction among them: ‘a father does not fight against the fathers, for all of them were communicants of a single Holy Spirit.’ St. John of Damascus collected not the personal opinions of the fathers but precisely patristic tradition. ‘An individual opinion is not a law for the Church,’ he writes, and then he repeats St. Gregory of Nazianzus: ‘one swallow does not a summer make. ‘And one opinion cannot overthrow Church tradition from one end of the earth to the other.’

Florovsky’s own view that the patristic tradition was a synthesis without contradiction…”

Fr. Florovsky’s view on this particular issue is the view of the Saints. One must either accept this view in faith or purify oneself so as to receive the grace to behold it for oneself.

Pope St. Martin the Confessor: “[W]hat one council of holy fathers is seen to decree, all the councils and absolutely all the fathers are recognized as confirming, through agreeing with one another successively in indissoluble accord in one and the same expression of faith.” (Lateran Council 649, First Session)

Being a former professor of Dogmatic Theology, I would like to know if he ever produced a summary of the Churches dogmatic theology for the layman. I have asked several priest for this, and have not received a satisfactory answer. There must be a better answer than go to seminary and find out.

Line 9 of the second paragraph should probably read: “Church as the Whole Christ, Head and Body” — although the error is in the source page that you link.

Fixed!

Fr. Damick,

Thank you for such a thorough and informative article. This one will take a few reads to grasp fully!

What do you mean by “eschatological tension”?

– James

My mistake – I missed that this was written by Dr. Lewis Shaw!