In a recent post at Glory to God for All Things, “The Un-Moral Christian,” Fr. Stephen Freeman critiques what he sees as common conceptions of Christianity as moral, defined as “the rules and standards by which we guide ourselves.” These, he writes,

are external and can be described and discussed. They are the rules by which we choose how to behave and by which we sometimes judge others. In this, everybody can be said to be “moral.” Atheists invariably adhere to some standard of conduct—it is just what human beings do. We are sometimes inconsistent and often cannot explain very well the philosophical underpinnings of our actions—but everyone has rules for themselves and standards that they expect of others.

To him, however, Christians ought not to think of themselves as moral, understood in this way, at all. He writes,

The nature of the Christian life is not rightly described as the adherence to an external set of norms and standards, even if those norms and standards are described as being “from God.” The “unmoral” life of Christians is a different mode of existence. The Christian life is not described so much by what it does as by how it does.

Instead, he insists that “the Christian life is not about improving our human behavior, it is about taking on a new kind of existence. And that existence is nothing less than divine life.”

On the one hand, I completely agree with him regarding the end or goal of our life in Christ: theosis or deification. This is certainly more than a matter of outward “adherence to an external set of norms and standards.” I also agree that an over-focus on external norms can trap one in a sort of Pelagian perfectionism that gives too much credit to human effort and too little to divine grace. And he is certainly right to say, “Our ‘moral’ efforts, when done apart from Christ, do not have the character of salvation about them.”

But, on the other hand, I argue that he’s ultimately overplaying his hand. To be more than moral, as Fr. Stephen is using the term, nevertheless requires first being moral. In particular, my thesis is twofold: Fr. Stephen (1) overlooks a common distinction among the Fathers between normative expectations for beginners in the faith versus the higher standard for the more mature (such as monastics and others who can devote their whole lives to the God), and (2) he undervalues the role of outward adherence to external norms as part of the process of internalization of the life in Christ.

One caveat: Fr. Stephen begins by noting that his differences with some may be merely semantic, but then, however, he continues to say that “the reason for [semantic differences] is important and goes beyond mere words.” Thus, I will try my best to stick to the substance of his essay rather than getting too caught up in terminological peculiarities, while, at the same time, acknowledging that some differences may be more apparent than actual.

That said, consider Fr. Stephen’s reflection on the teachings of Christ:

But think carefully about the commandments of Christ: “Be perfect. Even as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Morality withers in the face of such a statement. Christ’s teaching destroys our moral pretensions. He doesn’t say, “Tithe!” (Priests and preachers say “tithe”). Christ says, “Give it all away.” He doesn’t just say, “Love your neighbor.” He says, “Love your enemy.” Such statements should properly send us into an existential crisis.

By contrast, many of the Fathers, grounding their teaching in the Gospel, understood at least two, if not more, modes or standards of living the Christian life, which shed a different light on these more difficult commandments.

I begin with St. Ambrose. He writes, “Every duty [of the Christian life] is either ‘ordinary’ or ‘perfect.’” To Ambrose, ordinary duties correspond to a Christian appropriation of the Ten Commandments, given “from God” to Moses on Mt. Sinai, according to the Scriptures. “These are ordinary duties, to which something is wanting,” he writes. These norms are expected of all Christians as a basic starting point. Perfect duties, on the other hand, go beyond this standard. He grounds this in the story of the rich young ruler from the Gospel according to St. Matthew:

Now behold, one came and said to Him, “Good Teacher, what good thing shall I do that I may have eternal life?”

So He said to him, “Why do you call Me good? No one is good but One, that is, God. But if you want to enter into life, keep the commandments.”

He said to Him, “Which ones?”

Jesus said, “‘You shall not murder,’ ‘You shall not commit adultery,’ ‘You shall not steal,’ ‘You shall not bear false witness,’ ‘Honor your father and your mother,’ and, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’”

The young man said to Him, “All these things I have kept from my youth. What do I still lack?”

Jesus said to him, “If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow Me.” (Matthew 19:16-21)

St. Ambrose here picks up on Jesus’s condition: “If you want to be perfect.” To him, this goes beyond what is ordinary to a higher standard.

While this does seem to spark an “existential crisis” for the young man, who “went away sorrowful” (19:22), Ambrose, while being attentive to the text, through this distinction suggests a more hopeful reading, I think, than common pessimistic assumptions about the man’s fate, like that of the Apostles (“Who then can be saved?”—19:24). Indeed, St. Mark even notes that, after telling Jesus that he kept all the commandments, “Jesus, looking at him, loved him” (10:21). Christ challenges him to a higher standard, yes, but he does not criticize what he had already attained. Christ’s response, “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:16) is intended to counter such existential despair, not to commend it.

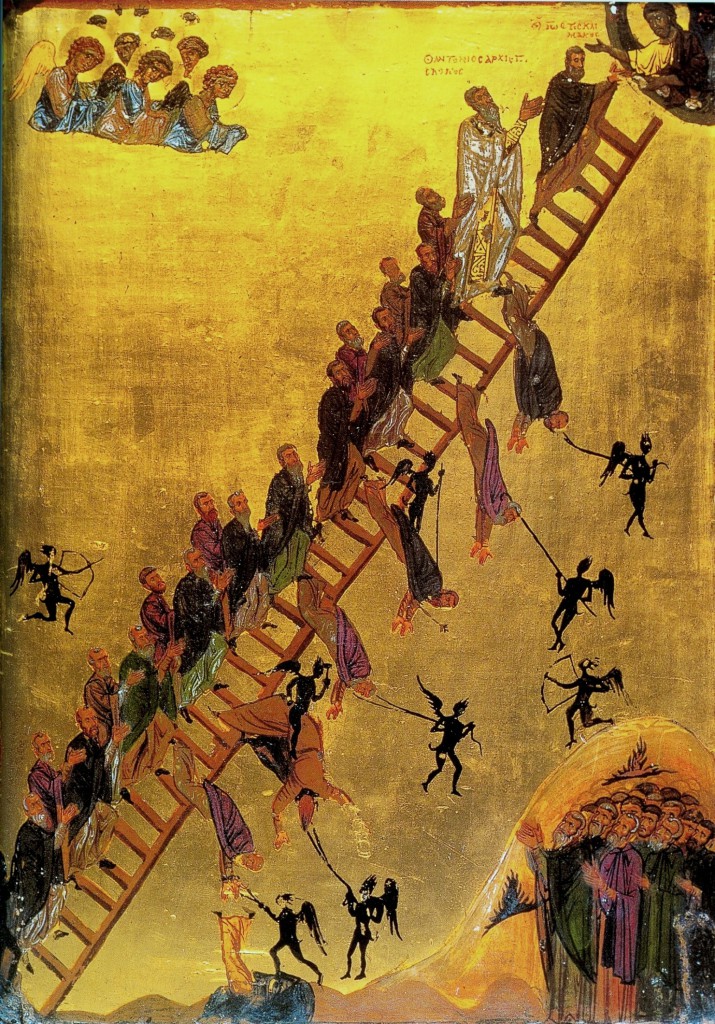

A similar distinction can be found in St. John Climacus’s Ladder of Divine Ascent. He writes,

Some people living carelessly in the world put a question to me: “How can we who are married and living amid public cares aspire to [the standard of] the monastic life?”

I answered: “Do whatever good you may. Speak evil of no one. Rob no one. Tell no lie. Despise no one and carry no hate. Do not separate yourself from the church assemblies. Show compassion to the needy. Do not be a cause of scandal to anyone. Stay away from the bed of another, and be satisfied with what your own wives can provide you. If you do all this, you will not be far from the kingdom of heaven.”

Don’t nearly all of these statements, which clearly resemble the Ten Commandments, have an external focus? They may not be reducible to that aspect (e.g. “carry no hate”), but it is notable that Climacus does not simply say, “Be perfectly humble” or “Be deified”—more clearly internally oriented commands—but rather, “Do whatever good you may.” There is a graciousness here reminiscent of the Didache, which, after describing the way of life in similar terms, states, “[I]f you can bear the whole yoke of the Lord, you will be perfect, but if you cannot, do what you can.” Those who are immature (myself most of all, no doubt) need to begin somewhere.

We may add to these the distinction found in St. Basil, St. John Cassian, St. John Climacus again, and St. Nicholas Cabasilas between three dispositions of obedience in our life in Christ. In Cassian’s Conferences, Abba Chæremon grounds this in his reading of the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-31). Cabasilas, a bit more succinctly, writes,

The Spirit permits us to receive the mysteries of Christ, and as it is said, to those who receive Him “He gave power to become children of God” (Jn. 1:12). It is to the children that the perfect love belongs from which “all fear has been driven away” (cf. 1 Jn. 4:12). He who loves in that way cannot fear either the loss of rewards or the incurring of penalties, for the latter fear belongs to slaves, the former to hirelings. To love purely in this manner belongs to sons alone.

Thus, slaves obey through fear of punishment, hirelings for desire for reward, and lastly children out of perfect love for love’s sake, unmindful of external punishments or rewards. This purity of heart, however, is the goal, not the beginning. As Proverbs teaches, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge” (1:7). Beginning with the more consequentialist and seemingly external (“fear of either the loss of rewards or the incurring of penalties”), as we spiritually mature, we move beyond our starting point. Then, and only then, will we too say with St. Antony: “Now I do not fear God, but I love him: for love casteth out fear.”

What the Fathers seem to be saying is the following: You would like to be deified but you do not know the way? You wish to love as a true child of God but you cannot? Learn from those who have walked this way before you. They began by fasting and praying and trying to fulfill the commandments, with much fear. Over time, these became a habit, internalized as a second, virtuous nature. Or rather, as the tarnish of passions is more and more cleared away from the image of God within you, your true nature as a child of God will shine through, restored in the likeness of Jesus Christ. This is firstly a matter of his grace, offered to you through the mysteries of the Church, but it is also a matter of synergia—you must cooperate with the work of this grace; you too must act. And in acting moral, you become more than merely moral, transfigured by the grace of God within you.

Fr. Stephen objects, “Our failures, including our moral failures, are but symptoms” of the true disease: lack of communion with God. But does not treating a disease also require basic treatment of the symptoms? Should we not expect our Great Physician to do both?

Similarly, if we wish to walk the narrow road that leads to life, we must do so one step at a time. If this means starting with basic, Ten Commandments, natural law, or even—to some degree—crudely consequentialist and “external” morality, some of which even a virtuous atheist may do or affirm, then so be it. We cannot expect to reach the end of the road, if we do not first start at the beginning.

Fr Stephen’s essay clearly subsumes all you’ve noted here. The target of his “attack” seems to be a Christianity that does not include the higher call as an ideal, one that mistakes moral success for spiritual healing and the goal of the Christian life.

In the comments of a related essay he notes that he is taking such a strong rhetorical stance because the connection between mere moralism and the Christian life is so strong that in order to comprehend (and keep) the distinction a rhetorical wall is required. In my experience, he’s right because we are all to one degree or another MTD’s.

No doubt King Reccard thought the filioque was a “strong rhetorical stance” against Arianism when he insisted upon adding it to the Creed at Toledo. We don’t combat error with more error, but the truth, even if it is more nuanced and complicated than a mere sound bite can convey.

While it’s a fun game you propose, out of respect for myself and for Dylan, I’m afraid I must decline to play.

Forgive me for any offense I have caused. This is far from a game for me. I believe very strongly that while Pelagianism is false, so is Complete Corruption, and we ought not to fight the first error with the rhetoric of the second. Not that I think Fr Freeman is teaching this at all, but in my opinion he has not struck the right balance. Perhaps my own rhetoric should be toned down – there is no heresy being taught here of course, but we also want to be very clear and unambiguous about the truth of the gospel.

Perhaps, so. It is an essay. A thought-piece. Not a revision of the Nicene Creed.

MTD’s (?)

Moral Therapeutic Deists.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Dylan. I have heard a few modern priests speak of the lofty goals of theosis and ontological change to which all of us Christians should be striving (and I have spoken of it to others myself). However, what they often times fail to teach is what you have shown here, that in order to begin the journey one must start walking, and in order to do that, one must be taught how to walk.

The biggest changes in my life have come from the two-fold approach of learning to work on the interior (prayer) while also placing a great amount of effort on the exterior (morals). Books like The Arena criticize the then-current condition of Russian monasticism stating that they were focused almost exclusively on the exterior. But then, when you read his book you find that he focuses almost exclusively on the heart and moralism (which in the Christian sense, I believe are intricately interwoven).

The best example I can give I think came from CS Lewis who said that faith and works (the interior and the exterior) can be thought of as two blades on on a pair of scissors. Each blade is useless without the other, and we end up lopsided if we stress one thing over the other.

Good job. I too love much of what Fr Stephen writes. Yet I also sense he over-

plays (states) his hand to make a point…which really weakens his point. He

does the same with “change” and “progress”. Much to learned here.

Excellent way to balance out Fr Stephens writings. I think it would be very helpful for people to read both for a fuller picture of the Orthodox view of morality and sin. I fear that somebody who read only Fr. Stephen would either stop going to confession, wrongly thinking he was claiming there is no objective morality for us to base a confession on. Or to fall into scrupulocity thinking they can never achieve the perfection Christ calls for and, therefore, are in a constant state of sin. As a former Catholic the idea of sin as a symptom of illness and not getting caught up in the idea of an act being “under the pain of sin” and therefore condemning one instantly to hellfire has been both freeing and difficult. But only in the True Church of Orthodoxy is that journey even possible.

Hyperbole is legitimate and should not, in and of itself, be characterized as improper, let alone false teaching: “If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters–yes, even their own life–such a person cannot be my disciple.” Luke 14:26.

This is an excellent and necessary amplification (corrective?) to Fr. Stephen’s post. I had the same misgivings and see the necessity and function of the moral commandments in the same way Pahman explains: Yes, theosis is the goal but the moral commandments illumine the path and direction toward it. How else do we know where to start? How else do we determine where the outer boundaries lie?

Sometimes I think we are too eager to draw out the distinctions between Orthodoxy and other Christian traditions that we end up muddling points important to Orthodox self-understanding. For example, the reduction of the moral dimension of salvation into a system of turgid juridical moralisms we see in some Protestant communions for example, does not negate the fact that specific commandments (“Thou shalt not kill, steal, commit adultery, etc.) are true, good, and necessary for direction about life in Christ.

“does not negate the fact that specific commandments (“Thou shalt not kill, steal, commit adultery, etc.) are true, good, and necessary for direction about life in Christ.”

Yes, but why? I have two young children, who will be tempted sorely by the culture’s anti-Christian anthropology. Moralism, even if it is justified by saying “it is a beginning – you will perhaps see why later – but perhaps not according to the Fathers” is not really good enough it seems to me. I would have never come to Orthodoxy from the position of the culture all those years ago if Orthodox Christianity did not offer something deeper than moralism. Modern man is in one important way not a coward: He does not bow to a god that says “because I say so” – and this is correct in my opinion because the whole in our heart is too big for that rather shallow answer…

Fr. Hans,

I want to add to my question to you by saying that I think you are doing very very important work within Orthodoxy around the whole “Orthodox Episcopalian” problem and our position vis-a-vis the culture. That said, I think your (and mine) responses has to have more weight behind them than a kind of moralism, a “the Tradition/scripture/Fathers” proof texting that is often done. The proponents of homosexualism, WO, etc. sound so moral, so “compassionate”, so reasonable. I think this is something Fr. Stephen is driving us to – the deep deep hole in the heart and the whole need for Christ, Salvation, etc. I don’t find the author of this present essay all that convincing because I think even beginners have to be given a vision that is beyond “mere morality”. Yes, the beginning – but it’s thin stuff indeed. I was quite young when I realized it was not enough and asked “but why?” – and so are our young people who then turn to the innovators and listen to their competing morality, and down then down the rabbit hole they go…

Christopher, that is my experience, too.

Your comment reminded me of my daughter (now 15) who is on the autism spectrum and mildly learning disabled. Figuring out the why of social norms and interactions and making inferences from language is very challenging for her. One of the forms her disorder has taken from early on when she finally started talking in sentences was asking questions. Constantly. Mostly questions she already knows the answer to. Then when she receives an answer (yet again) to her question, her immediate response is “why?” I often tell folks who meet her that she will never run out of questions and eventually their brains will overheat and start smoking! School speech therapists were working with her to try to extinguish this habit of asking why and started issuing a kind of behavioral deterrent for every time she did this. So, she figured out instead of asking “why” she could just say, “How come?” 🙂

It can be a very exasperating problem with my daughter, but I realize she is expressing a very human need. For those of us wired with this deep drive to make coherent sense of the spiritual universe we live in, it’s not enough to know the “right” moral answer. We also need to understand something of the deep why of our existence. Our spiritual need is for wholeness–true holiness–not just moral rectitude, and for that we need an experiential connection with God.

Christopher, the commandments are the banks of the river. You degrade them at your own peril. That’s the answer to the “but why?” question. There really is no other answer and it is confirmed through experience whether one obeys or breaks them.

This, then, is existentially true and thus real. It is not true because we believe it is true; it is true because it is true. Our only relationship to this existential reality is one where we either understand it or are ignorant of it.

I really don’t care that sometimes this ignorance is manifested as rigid moralistic structures. That’s a function of the desacramentalization of creation, where paradigms that mimic the face of Christ replace the life-giving Word of God; where systems replace creativity. Yes, it is indeed a type of idolatry where the life-giving spring is plugged with a muck that hardens into concrete, but it still has no bearing on the existential reality I mentioned above.

Fighting against these structures is fighting yesterday’s battles. They are no longer dominant in the culture. Everyone is a post-modernist these days, and those that aren’t live in a past where the only ones who hear them are the like-minded but they are graying and won’t be around in another 20 years. Their children are not listening.

I look at this question in terms of the cultural detritus that post-modernism leaves in its wake. Clearly the solution is not a return to the rigid moral structures, the paradigms that emerge as a result of a desacramentalized Christianity that is unable to uncover the knowledge that can heal the soul.

But neither is the solution to posit the commandments against a generalized notion of love and acceptance. That confusion leads to such things like the attempt to legitimize sodomy we see in some quarters of the Church.

I deal with too many young men confused by the moral relativism of post-modernism (to the point where it has damaged their souls) to diminish the importance and necessity of the commandments. Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice St. Paul says, and then be transformed by the renewing of your mind (“mind” is nous in the Greek). One follows the other, and the way in which we know how to conform our behavior (the “offering” or our bodies) to Christ is through the commandments.

Once this happens, Christ is increasingly encountered and the experience of authentic transformation — wholeness, self-integration, meaning, focusing of talents and creativity, purpose in life, victory of addictions, all the constituents that define man as man — can take place.

That is why the commandments are important.

Well. I’ve written a response. I suppose next time, I be sure to include lots of careful disclaimers. I’ve certainly not suggested any kind of libertine position. Indeed, I have ramped up the existential side of our failures to their proper point. But I have ceded certain points.

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2014/12/19/course-called-moral-response-critics/

Father Stephen, I think you may be backtracking a bit too quickly. If one is never accused of antinomianism, then one is not preaching grace.

Ah, Fr. Aidan! Doubtlessly true. But in truth, I think I pale beside Dostoevsky’s Christ, “Come you drunkards and prostitutes!”

And I heard in the distance…the lone braying of my dog…

FWIW, if all of this is not ontological, then St. Isaac either doesn’t work at all…

What is implied, but not explicit, thus far in the conversation is the “why” of morality. In listening to the dialogue both public and within Orthodox circles, there is a sense that morality exists for itself, or as a path to something bigger, but no one has connected the two.

Morality involves our obligation to “not me” – society or individual. It is exactly a focus on self that morality is designed to inhibit. The essential element of the fall of humanity is a change in our focus from a continual contemplation of our Creator, to a contemplation of ourselves – our own wants and will.

Our morality, as ascetical behavior, is facilitative of theosis because of this function – because our will, our self-focus (hedonism if you will) needs to be extinguished. And so, hypermorality (pharaseeism) is equally a sin – because the focus is still squarely on us.

What Fr. Stephen has written, to me, resonated very deeply – not because it alleviated our need for morality, but because it draws attention to the purpose of morality – the purpose of the Law, as a measuring rod for ourselves as well as a delineation of the path toward theosis. I see in his writing the connection between morality and theosis, which serves to enhance, not eliminate, the importance of morality in my estimation.

Yes! The “why” has to be there!

I understand the distinction (at least, I think I do) that Fr. Stephen is trying to address between our salvation as dependent upon a kind of external moralism vs. reliance on God’s grace for our salvation. However, the praxis/ascesis of our Orthodoxy is also manifested in our external relationships. If the label we apply to those “good” things we do or “acting with ‘good’ behavior/intent”, where “good” originating from God, (acknowledging also that only God is “good”), is “morals” then fine.

As one of my parish’s priests reminded us – we’re not called to be “good people”, we’re called to be “good Christians.” I take this to mean, if whatever morals I show forth externally aren’t Christ-like, or directed back at Christ as a reference point, or the Saints whose lives exemplified a Christ-like existence, then I continue to ‘miss the mark.’

Thus what I suppose those who would look in the mirror and say “hey, I’m a good person” without any reference back to Christ, would, so it would seem, be considered “moralists” for whom the evaluation of ones existence as positive/negative would be dependent only upon external morals as an end unto themselves.

Thus what may manifest as morals should be, for the Christian, evidence of that synergia & cooperation mentioned in the article, but only possible by Grace.

Dylan,

You speak about the way the 10 Commandments have an external focus and how as children we start out with these external practices that are measurable to our elders and guides. The fear of God is the beginning of wisdom. Amen. This of course correct.

The problem is that most of us stay there. Like the Pharisees we become whitewashed on the outside but have ceased to grow toward that holiness on the inside to which we have been called. The pure of us have never committed adultery, but we hide behind that in order to lust in our hearts every day. We haven’t committed murder but we hate our neighbor on a regular basis.

Morals held in this way are empty and useless. In fact they are harmful in that they lull us into a false sense of security. “At least I’ve never ______.”

One definition of holiness is to be made whole, to be healed. If we seek health by emptying ourselves so that we may be filled with Christ, then we will in actually be seen as living a moral life on the outside.

The problem with morality is that it’s not enough. It treats the symptoms but can never reach the disease that dwells within us. And in that case, we die just like everyone else – no matter how good we look on the outside. We must come to a place of admitting that nothing we do can fix this thing – and then invite God into our disgusting hearts, complete with all the filthy rags of righteousness we have laying around.

Keep your morality, but then meet God in your heart. Until we go there, we can go no further.

I don’t particularly disagree with the point Dylan wishes to make here, but I don’t see the need for him to make Fr. Stephen’s ministry his foil to do it. That is, I see no need to put down one aspect of ministry in order to exalt another. Indeed, it seems to me Dylan has rather missed the real point of Fr. Stephen’s writing.

Having lived 40+ years in the heart of conservative Evangelicalism before coming to Orthodox faith, I find there is no shortage of would-be spokesmen for “traditional Christian faith” to make public apologies for traditional Christian morality. I worked for several years for the publisher that launched Focus on the Family’s ministry, for instance. Like many, I’ve watched the culture wars grow shriller and shriller over the decades, meanwhile, to our chagrin the cultural decline marches on impervious. Now we have sexual scandal exploding in our face out of some of the most vocal “Christian” critics of cultural sexual ethics (Vision Forum, Bill Gothard, and now Bob Jones University), showing where Christianity’s moral vision leads when that moral vision is effectively divorced from the Source of its Life.

In contrast to all that, I’ve found Fr. Stephen’s writing to be a true oasis for my spiritually thirsty soul. I fervently hope Fr. Stephen won’t change a thing he is doing. Fr. Stephen’s blog slakes a deep thirst in our parched American moralistic landscape–he is drawing from a deep well.

Fr. Marty Watt, well said. Thank you.

FWIW, Karen, I don’t think Dylan’s piece uses Fr. Stephen’s ministry as a “foil” anywhere in it. He engages and replies critically, but there’s no put down going on.

The Church is big enough that we can disagree with one another respectfully and help each other sharpen our views and arguments.

I think “foil” is close enough that I stand by my statement in that regard. “Put down”, though, is an interpretation not necessitated by the content of Dylan’s post, so I concede your point there.

I agree that we can disagree respectfully and help each other sharpen our views and arguments (which is why I was also sorry you closed down comments on your last post so abruptly, since it appears I unwittingly opened a can of worms there with my initial–and only–comment). On the subject of your last post’s comments thread, I would have liked to express my appreciation for the perspective you offered in your reply to me there. I would have also liked to clarify that just because I happened across the link I provided and found it comment-worthy given the similar subject matter doesn’t mean I am among those eager to “rage against the Ecumenical Patriarch”, as you put it.

Yeah, that characterization wasn’t about you or your comment. (What you didn’t see were multiple comments that we didn’t let through.)

Ah, the “joys” of moderating a blog! 🙂

Thank you for the great post. I think that we often make things a little more complicated than they need to be.

St. John the Theologian: Little children, let no one deceive you. Whoever practices righteousness is righteous, as He is righteous…whoever does not practice righteousness is not of God… (1 John 3:7, 10 ESV)

St. Anthony the Great: Someone asked Abba Anthony, “What must one do in order to please God?” The old man replied, “Pay attention to what I tell you: whoever you may be: always have God before your eyes; whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the Holy Scriptures; in whatever place you live, do not easily leave it. Keep these three precepts and you will be saved.

The Fathers offered simplicity even when asked by the mature:

Abba Pambo asked Abba Anthony, “What ought I to do?” and the old man said to him, “Do not trust in your own righteousness, do not worry about the past, but control your tongue and your stomach.”

St. Theophan’s Commentary on Psalm 118 has much to offer to this discussion.

with respect: I suggest that it would be much more to the point to recall that:

” ..the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us….”

and ‘morality’ …is part of our path to eternal Life, but only part, one part of many in our

search/achievement of holiness.

A Bless-ed Nativitade to all

Charlie in Vancouver

Rather than expound on the impression of Fr Freeman’s postings, I thought I would show what is wrong with them by going through them and finding the falsehoods. I should note that there is much in them that is deeply valuable and true. That’s what makes the postings as a whole so very dangerous:

You are not doing better. You are not doing worse.

In truth, we don’t know how we’re doing. Only God knows. But we have internalized a cultural narrative and made it the story of our soul.

It’s not a “cultural narrative”, it’s Christianity. I once was lost but now I’m found. Twas blind but now I see. Christian faith stops people doing bad things and gets them doing good things. Christian faith really changes lives. Maybe Fr Freeman doesn’t see that in his church, but I’ve seen many lives changed. I’ve seen mine change. And on that basis, what he said was complete nonsense.

Our Christian lives are not a moral project.

The moral improvement (or progress) of our lives is not the goal of the Christian life. It is not even on the same page. We imagine that if we manage to tell fewer lies, or lust fewer times, or fast a little more carefully, and swallow our angry words more completely, we are somehow the better for it and have “made progress.” But this is not so.

Our lives are absolutely a moral project. They are this way because Christ is moral. He never sinned, and He is Holy. You can’t be like Christ and retain immorality – it’s a logical impossibility. And if we do all the things above, then yes, we have indeed “made progress”. We have started the process of healing our corrupted souls, and bringing Christ to those around us. If we lie less, we are not better off? What garbage. What utter garbage. And yet a cacophany of people applaud? Fr Freeman clearly has never been lied to if he does not understand the benefits both to him, and to the person lying, of them ceasing to lie.

St. Gregory of Nyssa once stated, “Man is mud whom God has commanded to become a god.” This is not the story of progress. We are not mud that is somehow improving itself towards divinity. There is nothing mud can do to become divine. And if we were honest with ourselves, we don’t even become better mud.

If becoming a god from mud is not the story of progress, then I just don’t know what is. Fr Freeman has asserted that these words do not express a belief in the heresy of Complete Corruption. If that’s so, he should have chosen better words, because that’s what these particular words express. Don’t urinate on my shoes and tell me it’s raining, as we (sort of) say here in Texas.

The failure to adhere to certain moral standards may have certain aspects of “sin” beneath it, but moral failings are not the same thing as sin.

A moral failing is by definition a sin. Sin is immoral. Immorality is sin. It’s doing things that are bad. Bad for us. Bad for others. Bad for God and for the cosmos. If we did not sin, the whole world would be transformed to glory and we would be who God meant us to be when He created us.

The habits of our culture are to think of sin in moral terms… But it is theologically incorrect. That is not to say that you can’t find such moralistic treatments within the writings of the Church – particularly from writings over the past several centuries. But the capture of the Church’s theology by moralism is a true captivity and not an expression of the Orthodox mind.

Snarky. Let’s just diss all the Saints of the past several centuries. Nice one. Now I haven’t been Orthodox for long, but I know enough to know that if you commit murder, that’s not just an intellectual or spiritual failing within yourself, but a real thing that happens in the real world, where somebody real ends up dead. You can’t say there’s no moral aspect to the sin of murder – that God somehow has no care for the real effects on the world of sin, but is only concerned with our internal spiritual state. That’s an old heresy, one of the oldest, and we call it gnosticism.

We do not ignore our false choices and disordered passions (habits of behavior). But we see them as symptoms, as manifestations of a deeper process at work. The smell of a corpse is not the real problem and treating the smell is not at all the same thing as resurrection.

To separate our spiritual processes from our deeds really is a Protestant phenomenon, not an Orthodox one (as I understand it). And the only way to treat the smell of a corpse is to resurrect it. God says of the Law – “do these things and you shall live”. Moral rectitude has resurrecting power. We know this, because Christ was resurrected by His righteousness – death could not hold someone who had never sinned – who had no blemish.

I have come to think of our salvation as similar to the reality of the sacraments. What do you see in the Eucharist? Does the Bread and the Wine go through a progressive change? Do we see a transformation before our very eyes?

What seems to be true is that our salvation is largely hidden – sometimes even from ourselves. The Christian faith is “apocalyptic” in its very nature – it is a “revealing of that which is hidden.”

This nearly made me puke. In my mind I wanted to recite a parody of Isaiah 61 where the Prophet tacks on at the end: “Of course this is all metaphorical for an invisible Jubilee that we only appreciate after we die”. No. Salvation is now. The Kingdom of God is now. This is not a Western distortion of the faith we preach, but True Orthodoxy. We don’t (just) get pie in the sky when we die. We say “The table is full-laden; feast ye all sumptuously. The calf is fatted; let no one go hungry away.”

In Orthodoxy, we don’t believe in a God who only works after death. We believe we are already dead to the world, that it is Christ who causes us to live, and that He does it RIGHT NOW.

It is not at all unusual in the lives of the saints for the sanctity of an individual to remain hidden until their death. This was the case for St. Nectarios of Aegina. He was dismissed by many, though seen truly by a few. But at his death, miracles began to flow from him, and suddenly the stories began to surface.

Yes, but it’s the exception that proves the rule. And Nectarios is a bad example – he actually was moral, but not recognised as such in this life. Most Saints either live virtuous lives, or they find faith after immorality and thereafter with labour find morality and true theosis.

I just don’t see how anyone could mistake this for genuine Orthodoxy. It’s a flirtation with Calvinism and Gnosticism that is the equal in dubiousness of anything that Fr Arrida has written about homosexuality. It is unclear as to its meaning, and fudges what is true about our faith.

I perhaps can understand, if converts come from a very moralising church background, how these posts might seem like wisdom to their eyes and ears. And yes, Pelagianism is a heresy, so let us not pretend that we can make ourselves righteous solely by our own effort. That is obviously not the teaching. And as for the “Orthodox Mindset (TM)”, no I don’t have that – Lord have mercy! But I have been an Evangelical Protestant for 30-odd years, and moralising Pelagianism is not my church experience. My background is very much one of large barns with rock bands singing songs about God being a hurricane and us being trees – where preachers would tell us that we have no need to be moral or follow rules because Christ has imputed righteousness to us, and that, if we would only realise this fact in our minds, we would evince the fruits of the Spirit and not sin as much in this life, and be transformed with new “spiritual” bodies in the next, because Jesus “has paid the price”. And so when I read Fr Freeman’s postings, how else should I react but to say that this, like the doctrines of the churches I left behind, is not the Orthodox faith! that we believe not in merely a spiritual or mysterious transformation, but a real, material one where people are really healed and the cosmos is truly revived in this current life that we live. And then also in the life beyond!

Forgive my harsh tone, but this is lukewarm nonsense, and after several days of digesting it I can do nothing other than spit out this so-called “meat”. The end of these doctrines is either despair, in which we give up our repentance and struggle against sin, or the cooling of love, where we divorce our inner spiritual life from the real world, and treat our moral failings as removed from our spirituality. God forbid!

Rather than expound on the impression of Fr Freeman’s postings, I thought I would show what is wrong with them by going through them and finding the falsehoods. I should note that there is much in them that is deeply valuable and true. That’s what makes the postings as a whole so very dangerous:

– “You are not doing better. You are not doing worse.

In truth, we don’t know how we’re doing. Only God knows. But we have internalized a cultural narrative and made it the story of our soul.”

It’s not a “cultural narrative”, it’s Christianity. I once was lost but now I’m found. Twas blind but now I see. Christian faith stops people doing bad things and gets them doing good things. Christian faith really changes lives. Maybe Fr Freeman doesn’t see that in his church, but I’ve seen many lives changed. I’ve seen mine change. And on that basis, what he said was complete nonsense.

– “Our Christian lives are not a moral project.

The moral improvement (or progress) of our lives is not the goal of the Christian life. It is not even on the same page. We imagine that if we manage to tell fewer lies, or lust fewer times, or fast a little more carefully, and swallow our angry words more completely, we are somehow the better for it and have “made progress.” But this is not so.”

Our lives are absolutely a moral project. They are this way because Christ is moral. He never sinned, and He is Holy. You can’t be like Christ and retain immorality – it’s a logical impossibility. And if we do all the things above, then yes, we have indeed “made progress”. We have started the process of healing our corrupted souls, and bringing Christ to those around us. If we lie less, we are not better off? What garbage. What utter garbage. And yet a cacophany of people applaud? Fr Freeman clearly has never been lied to if he does not understand the benefits both to him, and to the person lying, of them ceasing to lie.

– “St. Gregory of Nyssa once stated, “Man is mud whom God has commanded to become a god.” This is not the story of progress. We are not mud that is somehow improving itself towards divinity. There is nothing mud can do to become divine. And if we were honest with ourselves, we don’t even become better mud.”

If becoming a god from mud is not the story of progress, then I just don’t know what is. Fr Freeman has asserted that these words do not express a belief in the heresy of Complete Corruption. If that’s so, he should have chosen better words, because that’s what these particular words express. Don’t urinate on my shoes and tell me it’s raining, as we (sort of) say here in Texas.

– “The failure to adhere to certain moral standards may have certain aspects of “sin” beneath it, but moral failings are not the same thing as sin.”

A moral failing is by definition a sin. Sin is immoral. Immorality is sin. It’s doing things that are bad. Bad for us. Bad for others. Bad for God and for the cosmos. If we did not sin, the whole world would be transformed to glory and we would be who God meant us to be when He created us.

– “The habits of our culture are to think of sin in moral terms… But it is theologically incorrect. That is not to say that you can’t find such moralistic treatments within the writings of the Church – particularly from writings over the past several centuries. But the capture of the Church’s theology by moralism is a true captivity and not an expression of the Orthodox mind.”

Snarky. Let’s just diss all the Saints of the past several centuries. Nice one. Now I haven’t been Orthodox for long, but I know enough to know that if you commit murder, that’s not just an intellectual or spiritual failing within yourself, but a real thing that happens in the real world, where somebody real ends up dead. You can’t say there’s no moral aspect to the sin of murder – that God somehow has no care for the real effects on the world of sin, but is only concerned with our internal spiritual state. That’s an old heresy, one of the oldest, and we call it gnosticism.

– “We do not ignore our false choices and disordered passions (habits of behavior). But we see them as symptoms, as manifestations of a deeper process at work. The smell of a corpse is not the real problem and treating the smell is not at all the same thing as resurrection.”

To separate our spiritual processes from our deeds really is a Protestant phenomenon, not an Orthodox one (as I understand it). And the only way to treat the smell of a corpse is to resurrect it. God says of the Law – “do these things and you shall live”. Moral rectitude has resurrecting power. We know this, because Christ was resurrected by His righteousness – death could not hold someone who had never sinned – who had no blemish.

– “I have come to think of our salvation as similar to the reality of the sacraments. What do you see in the Eucharist? Does the Bread and the Wine go through a progressive change? Do we see a transformation before our very eyes?

What seems to be true is that our salvation is largely hidden – sometimes even from ourselves. The Christian faith is “apocalyptic” in its very nature – it is a “revealing of that which is hidden.””

This nearly made me puke. In my mind I wanted to recite a parody of Isaiah 61 where the Prophet tacks on at the end: “Of course this is all metaphorical for an invisible Jubilee that we only appreciate after we die”. No. Salvation is now. The Kingdom of God is now. This is not a Western distortion of the faith we preach, but True Orthodoxy. We don’t (just) get pie in the sky when we die. We say “The table is full-laden; feast ye all sumptuously. The calf is fatted; let no one go hungry away.”

In Orthodoxy, we don’t believe in a God who only works after death. We believe we are already dead to the world, that it is Christ who causes us to live, and that He does it RIGHT NOW.

– “It is not at all unusual in the lives of the saints for the sanctity of an individual to remain hidden until their death. This was the case for St. Nectarios of Aegina. He was dismissed by many, though seen truly by a few. But at his death, miracles began to flow from him, and suddenly the stories began to surface.”

Yes, but it’s the exception that proves the rule. And Nectarios is a bad example – he actually was moral, but not recognised as such in this life. Most Saints either live virtuous lives, or they find faith after immorality and thereafter with labour find morality and true theosis.

I just don’t see how anyone could mistake these musings for genuine Orthodoxy. It’s a flirtation with Calvinism and Gnosticism that is the equal in dubiousness of anything that Fr Arrida has written about homosexuality. It is unclear as to its meaning, and fudges what is true about our faith.

I perhaps can understand, if converts come from a very moralising church background, how these posts might seem like wisdom to their eyes and ears. And yes, Pelagianism is a heresy, so let us not pretend that we can make ourselves righteous solely by our own effort. That is obviously not the teaching. And as for the “Orthodox Mindset (TM)”, no I don’t have that – Lord have mercy! But I have been an Evangelical Protestant for 30-odd years, and moralising Pelagianism is not my church experience. My background is very much one of large barns with rock bands singing songs about God being a hurricane and us being trees – where preachers would tell us that we have no need to be moral or follow rules because Christ has imputed righteousness to us, and that, if we would only realise this fact in our minds, we would evince the fruits of the Spirit and not sin as much in this life, and be transformed with new “spiritual” bodies in the next, because Jesus “has paid the price”. And so when I read Fr Freeman’s postings, how else should I react but to say that this, like the doctrines of the churches I left behind, is not the Orthodox faith! that we believe not in merely a spiritual or mysterious transformation, but a real, material one where people are really healed and the cosmos is truly revived in this current life that we live. And then also in the life beyond!

Forgive my harsh tone, but this is lukewarm nonsense, and after several days of digesting it I can do nothing other than spit out this so-called “meat”. The end of these doctrines is either despair, in which we give up our repentance and struggle against sin, or the cooling of love, where we divorce our inner spiritual life from the real world, and treat our moral failings as removed from our spirituality. God forbid!

Courtesy trackback: http://goo.gl/PpPAKl. I offer a brief defense of Fr Stephen.

This article doesn’t understand the point Fr Stephen is making. Somehow. I encourage any interested readers to read the responses from both Fr Stephen and Fr Aiden. It clears things up and makes it quite clear that this “critique” didn’t need to be written in the first place.

Christopher, the commandments are the banks of the river. You degrade them at your own peril. That’s the answer to the “but why?” question. There really is no other answer and it is confirmed through experience regardless of whether one obeys or breaks them.

This, then, is existentially true and thus real. It is not true because we believe it is true; it is true because it is true. Our only relationship to this existential reality is one where we either understand it or are ignorant of it.

It doesn’t bother me much that sometimes this ignorance is manifested as rigid moralistic structures. That reduction is a function of the desacramentalization of creation, where paradigms that mimic the face of Christ replace the life-giving Word of God; where systems replace creativity. Yes, it is indeed a type of idolatry where the life-giving spring is plugged with a muck that hardens into concrete, but it still has no bearing on the existential reality I mentioned above.

Fighting against these structures is fighting yesterday’s battles. They are no longer dominant in the culture. Everyone is a post-modernist these days, and those that aren’t live in a past where the only ones who hear them are the like-minded but they are graying and won’t be around in another 20 years. Their children are not listening.

I look at this question in terms of the cultural detritus that post-modernism leaves in its wake. Clearly the solution is not a return to the rigid moral structures; the paradigms that emerge as a result of a desacramentalized Christianity that is unable to uncover the knowledge that can heal the soul.

But neither is the solution to posit the commandments against a generalized notion of love and acceptance that diminish the important and function of the commandments. That confusion leads to such things like the attempt to legitimize sodomy we see in some quarters of the Church. (We should not formulate our responses to paradigmatic moralism merely as a negation.)

I deal with too many young men confused by the moral relativism of post-modernism (to the point where it has damaged their souls) to diminish the importance and necessity of the commandments. Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice St. Paul says, and then be transformed by the renewing of your mind (“mind” is nous in the Greek). One follows the other, and the way that we know how to conform our behavior to Christ (the “offering” of our bodies) is by the commandments.

Once this happens (it works hand in hand), Christ is increasingly encountered and the experience of authentic transformation — wholeness, self-integration, meaning, focusing of talents and creativity, purpose in life, victory over addictions, all the constituents that define man as authentically man — can take place.

This is why the commandments are important.

My wife and I don’t argue as much as we did early in our marriage. Time seems to work things out as we get to know each other as two become one.

Most of our arguments would get so heated until finally we would realize we actually agreed. Pah’ching!!! Like two pots clanging together, or rather two heads head butting each other.

This is what we ended up calling it when we found ourselves arguing in agreement. “Hold on, we are pah’chinging again.”

But we were so focused on our own perspective during the arguing that we ended up wounding the other before we realized we were seeing the same elephant from a different side.

Sounds to me like Dylan has pah’chinged with Fr Stephen. I hope the two and the supporters of both can kiss and make up as my wife and I have on multitude of occasions.

As alluded to in Dylan’s article regarding slaves to sons, which I agree with his perspective, there are the 3 stages of development I have come to learn in my recent conversion and Chrismation to Orthodoxy, those of Repentance (understanding our shortcomings in keeping the commandments and law of love Christ taught from the Mount of Olives; not to be confused with the “bewitching law of Moses” some have alluded to in error as they defend Fr Stephen), of Illumination (which few Protestants understand in the Orthodox view), and Divination or Theosis (which level I believe and hope I correctly understand Fr Stephen is alluding to in his article).

As stated, I am a rookie Orthodox. I am new to this blog as well. I have actually been listening to the excellent lectures of Fr Andrew’s O/H archived podcasts this past week. I have found them most excellent Fr Andrew. I hope my wife listens to them.

My wife is not convinced of Orthodoxy yet. She is still struggling with certain things. “Blow ups amongst the Orthodox” like this are one of her hurdles. She actually told me about these two blogs today (12-20-14). Though I have been Chrismated into the Church, she is the one who reads the blogs.

Having said that, is there any possibility of dividing the blogs into levels of Repentance, Illumination, and Theosis?

No? No. I can see how difficult that would be. Maybe bloggers and podcastors could self rate their posts like the movies do: you know like rated G, PG, PG-14, and R, etc. Maybe some kind of organizing especially for the new inquirers and new converts to at least have an idea of what they are about to expose themselves to.

I say this a bit tongue in cheek, not to be rude or disrespectful, but with hopes to lighten the mood to make a point.

The modern Non-Orthodox world is mostly a shallow creek and barely understanding the depth of the Orthodox ocean they now find themselves diving into. It is easy to see how people can pah’ching here. If the Orthodox pah’ching like this, how much more for those who pop in for the first time or even their first year?

Well, I’m not sure if I completed my thoughts well enough. I’m actually at my second job posting this during some down time. I hope I helped somehow and I hope Dylan will take his argument to Fr Stephen’s blog for clarification prior to roasting him in a separate blog.

Dean Martin’s Roasts were quite fun and entertaining to hear and watch. We don’t need entertainment or coarseness, but I hope the Orthodox roasts can be more collegiate and gentle, especially for those of us still on baby milk.

Thank you for allowing me to post.

The whole episode with these posts has been incredibly disturbing. Not so much what Father Freeman himself wrote (though I am upset that so few have bothered to critique the language he uses), but the response – the anger and bitterness that seems to be coming out of people, the defiance and bitterness that anyone dare question them. We are accused of having a Protestant mindset, and of requiring milk while those who are enlightened feast on meat. I don’t know what to say about it other than “good luck with that”.

My Orthodox faith is one where spiritual enlightenment and practical morality are the same thing. There is no separation between the two. It is wrong to focus on living a moral life as an end in itself. But it is also wrong to pretend that the spiritual life is above such things. Orthodoxy is nothing if not a faith of the material world, of icons, of a Saviour who came in the flesh, deifying flesh and healing it. He brings the Kingdom of God to us in the here and now. We are not Calvinists who claim that we “cannot even become better mud”. We are not Gnostics who pretend that sin is just a spiritual problem instead of a problem with both soul AND body – our will AND our actions. We don’t claim that salvation is an invisible phenomenon that cannot provide tangible material healing us in this life. No, we are Orthodox, and Christ is our physician in this life, and in the next!

Am I wrong about all this? It seems to me like there is a group of people who have perhaps been brought up in very moralizing churches that are latching on to a more spiritual interpretation of faith as if the two are opposites (and then calling it “Orthodox”). But you can find this sort of thing in any big box Evangelical barn where they sing songs about God being a hurricane and us being trees. That’s not what we believe! And to even say that one STARTS with morality, then moves to something more immaterial essentially concedes the argument. Yes indeed! we start with morality – fasting, prayer, good works, ascesis… but we don’t stop those things, we just add to them a deeper spiritual understanding. And in this way… we do better! Yes we do!

I think the issue here is not what you critiqued, but who. Fr. Steven has written a number of wonderful articles over the years. I have enjoyed a great many of them when I take the time to read them. I should probably read more. But when you critique someone’s favorite author you tend to get some backlash from his greatest fans. I might do the same thing if someone were to start critiquing Tolkien. Fr. Stephen has been gracious with his response. Let his fans follow him in his kind demeanor and pleasant interactions.

John

Blair,

Take what you may from these words of the Saints – and let us pray for one another in love.

Saint Mark the Ascetic writes;

“Firstly, we know that God is the beginning, middle, and end of every good. But it is inconceivable for the good to be the object of action or to be believed in except in Christ Jesus and Holy Spirit. Every good is given by the Lord providentially; and he who believes thus will not lose it.

He who is humble and engages in spiritual work, when reading the Divine Scriptures will take everything to apply to himself and not to someone else….He who has some spiritual gift and feels sympathy for those who do not have it, though the sympathy preserves the gift. But the arrogant man will lose it, being overcome by arrogant thoughts.

Do not attempt to explain something difficult by disputation, but through the means which spiritual law indicates; through patience and prayer and unwavering hope.

Thus, a merciful heart will obtain mercy…The law of freedom teaches every truth. Many read this according to their knowledge, but few understand it, each in proportion to his fulfilling of the Commandments. Do not seek the perfection of the fulfilling of the Commandments in human virtues, for it is not found perfect in them. Its perfection is hidden in the Cross of Christ.

The law of freedom is read through true knowledge, is understood through the fulfilling of the Commandments, and is completed through the mercies of Christ.

When through conscience we are forced to carry out all the Commandments of God, then we shall understand that the law of the Lord is perfect; that it is put into practice in our fair deeds, but cannot find perfect fulfillment in human actions without the mercies of God.

Those who have not reckoned themselves debtors of every Commandment of Christ read the law of God in a non-spiritual manner, “understanding neither what they say nor whereof they affirm” (1 Tim 1:7) Therefore they think that they fulfill it by their deeds.

There is reproof in accordance with wickedness and self-defense; and there is another reproof, which is in accordance with God and truth…If you say that you reprove him according to God, first expose your own evils.

God is the source of every virtue, as the sun is of daylight. Having done a virtuous act, remember Him who says that “without me ye can do nothing.” Every good from God comes providentially. But this fact mysteriously escapes…notice…

Ignorance disposes one to speak in opposition to what is profitable; and when it becomes bold, it increases the consequences of vice. Investigate your own evils and not those of your neighbor; and your spiritual workshop will not be taken away. Suffering no loss, accept afflictions…

Show yourself mentally to the Master. “For man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.” (1 Sam 16:7) Those of us who have deemed worthy of the washing of regeneration offer good works not for recompense, but for the preservation of the purity that has been given us. Every good work which we perform through our own nature makes us refrain from the opposite, but without grace is incapable of adding to our sanctification.

The self-restrained man abstains from gluttony…he who is meek abstains from agitation; he who is humble abstains from vainglory; he who is obedient abstains from contentiousness….

Now abstinence from sin is a work of nature, not an exchange for the Kingdom. Man scarcely preserves what is proper to his nature; but Christ grants sonship throug the Cross.

“The flesh desireth against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh (Gal 5:17)

Saint John Cassian says;

Our eighth struggle is against the demon of pride, a most sinister demon, fiercer than all that have been discussed up till now. He attacks the perfect above all and seeks to destroy those who have mounted almost to the heights of holiness. Each of the other passions that trouble the soul attacks and tries to overcome the single virtue which is opposed to it, and so it darkens and troubles the soul only partially. But the passion of pride darkens

the soul completely and leads to its utter downfall. we should feel fear and guard our hearts with extreme care from the deadly spirit of pride. When we have attained some

degree of holiness we should always repeat to ourselves the words of the Apostle: “Yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me’ (1 Cor. 15:10), as well as what was said by the Lord: ‘Without Me you can do nothing’ (John 15:5). We should also bear in mind what the prophet said: ‘Unless the Lord builds the house, they labor in vain that build it’ (Ps. 127:1), and finally: ‘It does not depend on-man’s will or effort, but on God’s mercy’ (Rom. 9:16).

Even if someone is sedulous, serious and resolute, he cannot, so long as he is bound to flesh and blood, approach perfection except through the mercy and grace of Christ. James himself says that ‘every good gift is from above’ (Jas.

1:17), while the Apostle Paul asks: ‘What do you have which you did not receive? Now if you received it, why do you boast, as if you had not received it?’ (1 Cor. 4:7). What right, then, has man to be proud as though he could achieve perfection through his own efforts ?

The thief who received the kingdom of heaven, though not as the reward of virtue, is a true witness to the fact that salvation is ours through the grace and mercy of God. All of our holy fathers knew this and all with one accord teach that perfection in holiness can be achieved only through humility. Humility, in its turn, can be achieved only through

faith, fear of God, gentleness and the shedding of all possessions. It is by means of these that we attain perfect love, through the grace and compassion of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory through all the ages. Amen.”

Nikitas Stithatos –

” A passion is not the same thing as a sinful act: they are quite distinct. A passion operates in the soul, a sinful act involves the body. For example, love of pleasure, avarice and love of praise are three particularly noxious passions of the soul; but unchastity, greed and wrong-doing are sinful acts of the flesh. Lust anger and arrogance are passions of the soul produced when the soul’s powers operate in a way that is contrary to nature. Adultery, murder,theft, drunkenness and whatever else is done through the body, are sinful and noxious actions of the flesh.

The three most general passions are self-indulgence, avarice and love of praise… If it is but recently that you have embarked on the struggle for holiness and ranked yourself. against the passions, you must battle unremittingly and through every kind of ascetic hardship against the spirit of self-indulgence.

You must waste your flesh through fasting, sleeping on the ground, vigils and night-long prayer; you must bring your soul into a state of contrition through thinking on the torments of hell and through meditation on death; and you must through tears of repentance purge your heart of all the defilement that comes from coupling with impure thoughts and giving your assent to them.

God deserts those engaged in spiritual warfare for three reasons: because of their arrogance, because they censure others, and because they are so cock-a-hoop about their own virtue. The presence of any of these vices in the soul prompts God to withdraw; and until they are expelled and replaced by radical humility, the soul will not

escape just punishment.

It is not only passion-charged thoughts that sully the heart and defile the soul. To be elated about one’s many achievements, to be puffed up about one’s virtue, to have a high idea of one’s wisdom and spiritual knowledge, and to criticize those who are lazy and negligent – all this has the same effect, as is clear from the parable of the publican and the Pharisee (cf. Luke 18:10-14).

Do not imagine that you will be delivered from your passions, or escape the defilement of the passion-charged thoughts which these generate, while your mind is still swollen with pride because of your virtues. You will not see the courts of peace, your thoughts full of loving-kindness, nor, generous and calm in heart, will you joyfully enter

the temple of love, so long as you presume on yourself and on your own works.

If after strenuous ascetic labor you receive great gifts from God on account of your humility, but are then dragged down and handed over to the passions and to the chastisement of the demons, you must know that you have exalted yourself, have thought much of yourself, and have disparaged others. And you will find no cure for or

release from the passions and demons that afflict you unless you make use of a good mediator and through humility and awareness of your limitations you repent and return to your original state. Such humility and self-knowledge lead all who are firmly rooted in virtue to look upon themselves as the lowest of created things.

When you know yourself you cease from all outward tasks undertaken with a view to serving God and enter into the very sanctuary of God, into the noetic liturgy of the Spirit, the divine haven of dispassion and humility. But until you come to know yourself through humility and spiritual knowledge your life is one of toil and sweat. It was

of this that David cryptically spoke when he said, ‘Toil lies before me until I enter the sanctuary of God’ (Ps. 73:16-17. LXX).

To know yourself means that you must guard yourself diligently from everything external to you; it means respite from worldly concerns and cross-examination of the conscience. Once you come to know yourself a kind of super rational divine humility suddenly descends upon the soul, bringing contrition and tears of fervent compunction

to the heart. Acted upon in this way you regard yourself as earth and ashes (cf. Gen. 18:27), and as a worm and no man (cf. Ps. 22:6). Indeed, because of this overwhelming gift of God, you think you are unworthy of even this wormlike form of life.

Truth is not evinced by looks, gestures or words, and God reposes not in these things but in a contrite heart, a humble spirit and a soul illumined by the knowledge of God. Sometimes we see someone speaking to all comers in an outwardly obsequious and humble manner, while inwardly he pursues the praise of men and is filled with selfconceit, guile, malice and rancor.

God looks not at the outward form of what we say or do, but at the disposition of our soul and the purpose for which we perform a visible action or express a thought. In the same way those of greater understanding than others look rather to the inward meaning of words and the intention of actions, and unfalteringly assess them accordingly. Man looks at the outward form, but God looks on the heart (cf. 1 Sam. 16:7).

Not-sinning does not make us “better.” That is Fr. Freeman’s point. The Pharisees kept the law better than anyone, but they were dead on the inside. We can be moral as much as our strength allows, but it will not bring healing. That only comes by union with Christ in the Holy Spirit. This is the teaching of the saints and our Holy Tradition. Fr. Freeman is expressing this and nothing else.

Thinking that “being moral” will somehow bring about righteousness is the flawed thinking here. It is utterly forensic and completely removed from reality. This is the other point Fr. Freeman is trying to make; salvation is ontological.

St. Theophan agrees: “I suppose that you remember and still keep in mind that a Christian is not an ordinary person, being formed instead from nature *and* grace. I would like to clarify something for you at this point: Those who are saved, that is, those who will enter the eternal Kingdom of God, are only those in whom grace dwells; not secretly, but openly, permeating our entire essence and becoming even outwardly visible, absorbing, as it were, our entire nature. Heed the word of the Savior! He says that the Kingdom of God is like when a woman had added leaven to dough. Once it has received the leaven, it does not rise all at once; it will do so in its own time. The leaven within it permeates the dough little by little, and the entire dough becomes leavened. Bread baked from this is light, aromatic, delicious. It is exactly the same thing with grace which has been added to our nature: it does not permeate everything all at once; instead, it does so little by little. Then, once it has permeated everything, one’s entire nature is filled with grace.”

“Being moral” is like trying to have the dough of our lives rise without leaven. It won’t happen. Leaven comes first, and then the bread is transformed. Getting out of our own way and letting the leaven get to work (i.e. “acquiring the Spirit”) is what we are called to do.

I’m just staggered that anyone could seriously hold the viewpoint that being moral does not bring about righteousness. Being moral IS righteousness. Now sure, one can be moral for reasons of pride or some other motive, but the moral act (or inaction) stands, and makes a material difference to the cosmos, even if it does no credit to the person “being moral”.

To think that we can follow Christ and unite ourselves to Him without external, tangible, material moral practice is far far removed from His teaching and the teachings of the Fathers. It’s just gnosticism. For the dough to rise, one has to work the leaven through it.

Or does that happen “invisibly”? I am picturing a Priest standing proudly beside a tortilla and telling me that it is, in fact, in the sight of God, a loaf of bread!

Dear Blair,

“To think that we can follow Christ and unite ourselves to Him without external, tangible, material moral practice …”

What you speak of here are known as “fruits of the Spirit.” Who here has said that we ought not have fruits of the Spirit, or that we ought not “work out our salvation with fear and trembling.”? To say that morality is not capable of creating righteousness IS NOT the same thing as saying that one must not resist evil and do good. Perhaps, the following will help illuminate the difference…

“I’m just staggered that anyone could seriously hold the viewpoint that being moral does not bring about righteousness. Being moral is righteousness.”

Is it?

Saint John Chrysostom, “Being filled with the fruits of righteousness which are Jesus Christ unto the praise and glory of God; i.e. holding, together with true doctrine, an upright life. For it must not be merely upright, but filled with the fruits of righteousness. For there is indeed a righteousness NOT according to Christ, as, for example a simple moral life. Homily II Phillipians verse 11.

John 15:4-5 “Abide in Me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself unless it abides in the vine, so neither can you unless you abide in Me. “I am the vine, you are the branches; he who abides in Me and I in him, he bears much fruit, for apart from Me you can do nothing.”

Also see :

Romans 3:20-26

Romans 4:1-10

1 Cor 1:30 – “It is because of Him that you are in Christ Jesus, who has become for us wisdom from God—that is, our righteousness, holiness and redemption. Therefore, as it is written: “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord.”

Galatians 2:20 “The life I now live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. I do not set aside the grace of God, for if righteousness could be gained through the law, Christ died for nothing!”

None of these things negate living as a slave (doulos) of Christ…and allowing Him to work in and through us, deifying us as we empty ourselves of our own will. One can be “moral” and never be righteous… so says St. John Chrysostom … we must ” …not be merely upright, but filled with the fruits of righteousness. For there is indeed a righteousness NOT according to Christ, as, for example a simple moral life.”

The righteousness not according to Christ is a life that lives solely by believing that being “moral IS righteousness.” The righteousness that IS according to Christ is a life informed by the knowledge that Christ HIMSELF IS OUR righteousness…and we merely allow HIM to work HIS leven through us by our humility, self-sacrifice and ascetic emptying of our nous and kardia of any self-will. We DIE to ourselves. In this way we continue to unite ourselves with Christ, and allow HIS righteousness to become our righteousness.

Of course, we will change…of course we will exhibit transformation of our external behaviors, of course we will display “fruits of righteousness.” But these flow FROM Christ’s righteousness, as a stream of living water. No stream precedes it’s source, just as no true works of righteousness can precede their source; which is CHRIST. John 4 illustrates this. “If anyone is thirsty, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture said, ‘From his innermost being will flow rivers of living water.'” whoever drinks from the water that I will give him will never get thirsty again–ever! In fact, the water I will give him will become a well of water springing up within him for eternal life.”

To say that one can become righteous through moral effort is to exchange the brackish stagnancy of our own works with the living water and works that flows from Christ and HIS righteousness. OUR WORKS ARE NECESSARY! both Faith and Works continue to justify us…(justify= put us in right relationship i.e” communion” with Christ) BUT OUR WORKS ARE NOT RIGHTEOUSNESS…but fruits of righteousness.

Righteousness IS Christ. He is the vine. He is the well.

Blair, forgive me, but it seems to me you are ignoring here what Aaron says on December 26 below.

As others have pointed out, you miss Fr. Stephen’s point/context and are (perhaps unwittingly) merely creating straw men to tear down. Fr. Stephen is not endorsing a faith without works theology as you argue here. If you had been a regular reader of his posts over the last several years (instead of ripping his statements in one particular post out of their full context, essentially putting words in his mouth and then picking them apart), you might realize he’s about as far from being Gnostic in his views as they come. Rather, Fr. Stephen is challenging the temptation to externalism–the temptation to reduce the Church’s teaching of theosis to external performance of a set of behavioral rules fueled by self-effort (which is actually a form Gnostic tendencies can take as well).

My observation, as a long-time reader of his blog, is that his whole recent series of posts could be more properly seated and understood as an exposition and expansion on the lesson found in Christ’s parable of the Publican and the Pharisee.

Blair,

Father freeman affirms “change” and “transformation” of the Christian…but not “progress” as the modern and post-modernist mind perceives them. We do not do better. We are made better.

We are changed, into new creations. But we do not progress. We are gods by the grace of God….not by our own filthy rags progressing us. Prayer, ascesis, fasting, almsgiving are ways to empty ourselves of self-notions of pride and achievement. They are the means of emptying ourselves to the presence and grace of Christ to work in our lives, so that we become “vessels.”

Vessels which are full of self-righteousness…vessels which believe it is “WE” that do better are not allowing themselves to be empty so that the Spirit can fill us and HE can change us. We do have a role to play…we crucify ourselves and suffer, just as HE suffered. We empty ourselves of conceit and receive glory upon glory…grace upon grace. We receive, we do not achieve.

These guys are brainwashed by the forged books called Romans and Galatians, and completely reject the gospels, especially the Sermon on the Mount. Jesus taught morality and the epistular “Paul” taught Gnostic anomia. The only historical Paul is the one in Acts, and the “Paul” of the epistles (aside from the pastorals, of course) is just a forged literary production by Marcion the Gnostic, which explains why this is.

David, your Radical Critical view that Romans and Galatians are “forgeries”, etc., has little weight for an Orthodox Christian. We don’t take our cues as to the meaning of our Scriptures from 19th century German or Dutch higher critics. For the Orthodox, the canonicity of the Scriptures as well as the broad parameters of their proper interpretation has been a settled issue for more than 1,500 years. It was the early Church Fathers of the Orthodox Church of the post-apostolic era that identified Marcion as a heretic in the first place–yet, interestingly, these Orthodox Church Fathers knew how to properly interpret the Apostle Paul in spite of Marcion’s attempt to co-opt the apostle for his own heretical purposes.

Orthodox Christian faith is not antinomian. Neither is it moralistic. It is something else altogether–it is “theosis”, the total transformation of the believer from the inside-out to be like Christ, through a participation within the Church, Christ’s very Body, in the energies of God Himself through the grace of the Holy Spirit.

I’m not sure where this is coming from (or if it’s a bit), but no critical scholar, including atheists, religious, and non-religious of all types, would deny that Romans and Galatians are authentic epistles of Paul. In fact, they are held as being exemplars of the authentic Paul.

Eric, your comment makes me suspect this 19th century academic fad has long been debunked and superseded by new theories in academic circles (or a return to more traditional perspectives). Here is where David’s perspective seems to be rooted:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical_criticism

Perhaps there are a few old liberal academics still enamored of this school of thought?

People who hold to such radical views would be considered academic heretics to some degree or at least occupying an academic backwater that is, for all intents and purposes, without merit or worth responding to in mainstream academia.