We’ve mentioned a number of times on the Lord of Spirits podcast that usually where you see faith or believe in the Bible it is better translated “faithfulness” or “be faithful to.” Many verses of the Scriptures become much clearer when read this way, e.g., “For by grace you have been saved through faithfulness” (Eph. 2:8a). The many references to “increasing” faith also make more sense this way — they don’t mean “believe harder” but rather “be more faithful.”

It’s worth noting that English once had this sense for both faith and believe and still has some remnants of this sense.

The sense of faith as loyalty is still preserved in the word faithful (which does not mean “full of belief”!) but also the phrases keep faith and break faith. Faith entered into English from Latin “fides” via French in the mid-13th c. and initially referred to loyalty and ongoing trust. In the early 14th c. it acquired the sense of “mental assent in the face of incomplete evidence.”

Believe itself did not acquire its modern sense of “be convinced of something” until the 14th c. The term derives from an earlier form of love and originally had the Old English prefix ge-, which gets used in various ways but was mainly an intensifier or denoted the idea of “completion.” So, ge-lyfan had the sense of truly loving. It was sometimes used for ideas, which is where you get the eventual sense of “agree that this is true” / “be convinced of.”

A lot of the words we have in English Bibles originally reflected a more traditional and Orthodox understanding, but with the words redefining over the centuries (as happens to words), doctrinal understanding of them also shifted.

It is hard to tell where the chicken and where the egg is with these things — did usage affect doctrine, or did doctrine affect usage? Or both? It’s hard to tell. The Reformation touches off in the early 16th c., but it didn’t come out of nowhere but built on earlier doctrinal developments.

Nevertheless, now sola fide (‘faith alone’) is firmly associated with the Reformation, with the fide not really meaning fidelity but rather agreement, especially since faith was opposed to good works by Luther in his misreading of St. Paul. Thus, in teaching our doctrine, it’s important for Orthodox Christian English speakers to reiterate in updated English what was once more straightforward in the English (and other languages) of former times.

One final note: In the Nicene Creed, we begin with “I believe in one God” (or “We believe…” in the conciliar texts), and many people take this to mean “I affirm that only one God exists.” Yet the same people who formulated that Creed also wrote of the gods of the nations as actually existing — they are demons — because the Bible itself treats these gods the same way.

Given the above about believe, we can see that the “I believe” in the Creed is not a statement of assent to a doctrine but rather of loyalty — “I am faithful to one God.” The rest of the dogmatic statements of the Creed are also affirmations of loyalty. Of course that requires agreeing to these concepts, but there is no faithfulness without action, as St. James told us (James 2:26).

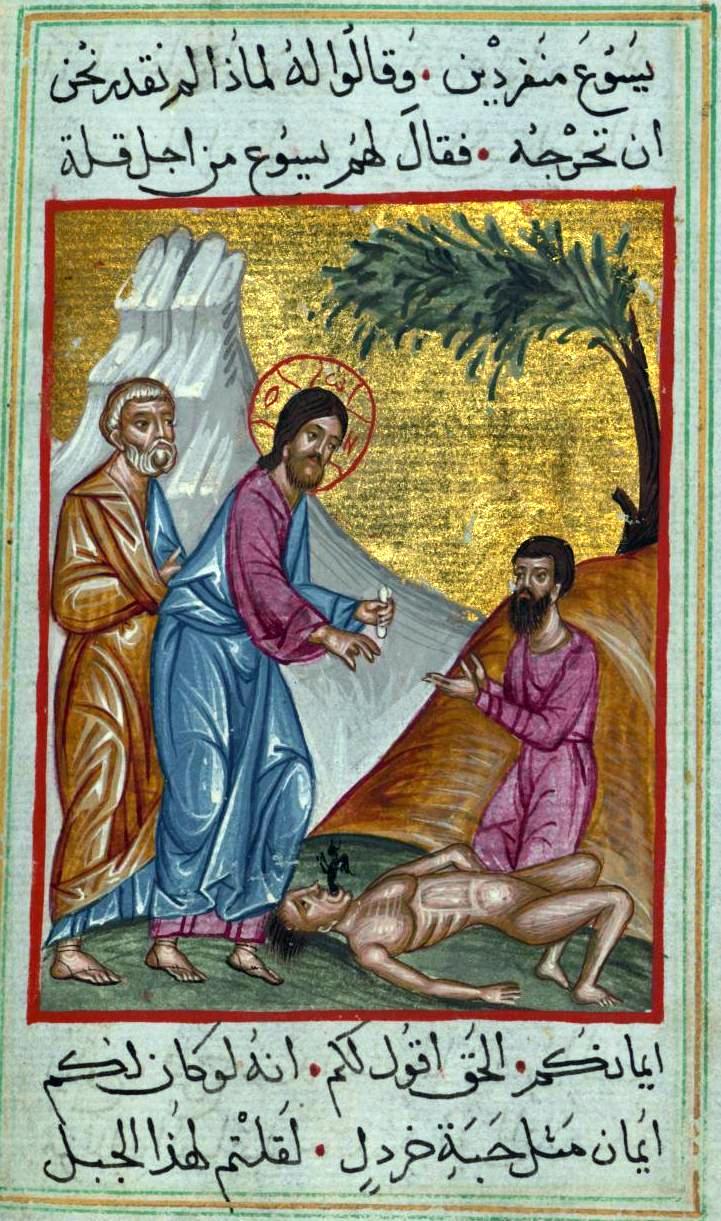

(Image: 17th c. Arabic manuscript icon of the healing of the demon-possessed boy, the son of the man who cried out “Lord, I believe; help my unbelief,” Mark 9:24.)

Thanks for this, Father. “Faithfulness” does make more sense. But it does sound odd (to my ears) to ascribe the father of the man as saying, “I am faithful, help my lack of faithfulness!”.

So when the scriptures like Deuteronomy 7:9 say that God is faithful, is that a similar concept? That would make sense, seeing as God doesnt have need to “believe harder” in us, but rather, is loyal to us.