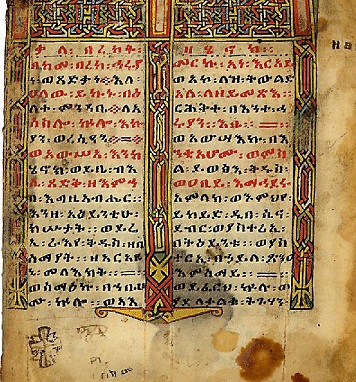

The final portion of the Book of Enoch, comprising what is generally numbered as chapters 91-108, is commonly referred to as the Epistle of Enoch. Though ‘epistle’, through its New Testament usage, gives the idea of a letter, these chapters are not purported to be a letter written by Enoch. Rather, they purport to be a record of Enoch’s parting words to his son Methuselah and his extended family. Depending upon the translation which one reads, 1 Enoch may end with a brief, two verse chapter 105, may continue through to chapter 108, or may jump from the former ending to chapter 108. Some translations incorporate all of the material sometimes numbers as chapters 105-108 as verses of chapter 105. This is based on our somewhat scattered manuscript evidence. There is the complete Book of Enoch found in the Old Testament in Ge’ez in Ethiopian Bibles. There are also partial Greek and Aramaic manuscripts of 1 Enoch of earlier provenance. The manuscript evidence incorporates, or fails to incorporate this final material in various ways. It appears that in at least some language traditions, fragments of Enoch tradition were appended to the end of the Book of Enoch following its five major parts being edited together. It is unclear whether these fragments were written fragments added to produced texts in the scribal process, or if they were oral tradition fragments incorporated into the text in written form for the first time.

The final portion of the Book of Enoch, comprising what is generally numbered as chapters 91-108, is commonly referred to as the Epistle of Enoch. Though ‘epistle’, through its New Testament usage, gives the idea of a letter, these chapters are not purported to be a letter written by Enoch. Rather, they purport to be a record of Enoch’s parting words to his son Methuselah and his extended family. Depending upon the translation which one reads, 1 Enoch may end with a brief, two verse chapter 105, may continue through to chapter 108, or may jump from the former ending to chapter 108. Some translations incorporate all of the material sometimes numbers as chapters 105-108 as verses of chapter 105. This is based on our somewhat scattered manuscript evidence. There is the complete Book of Enoch found in the Old Testament in Ge’ez in Ethiopian Bibles. There are also partial Greek and Aramaic manuscripts of 1 Enoch of earlier provenance. The manuscript evidence incorporates, or fails to incorporate this final material in various ways. It appears that in at least some language traditions, fragments of Enoch tradition were appended to the end of the Book of Enoch following its five major parts being edited together. It is unclear whether these fragments were written fragments added to produced texts in the scribal process, or if they were oral tradition fragments incorporated into the text in written form for the first time.

The main body of the Epistle of Enoch, before the various endings, consists of Enoch relating a vision to his family because he has been told he is about to ascend to the heavens. After describing the vision, which lays out the future history of the world as a series of weeks. These epochs begin with Enoch’s own and continue until the End of Days and the final judgment. After describing the vision of the future, Enoch then applies the vision by giving counsel and direction to his family on how to live in the coming ages. These homiletical applications are, of course, aimed primarily at the readers of the text in those latter ages. This means that the Epistle of Enoch, written in the Hasmonean period (c. 150 BC), gives us an early and prime example of apocalyptic preaching during the Second Temple period. As will be seen, there are clear connections in both form and content to Christ’s own preaching as recorded in the Synoptic Gospels, justifying and facilitating an apocalyptic interpretation of the latter.

The basic themes of this preaching are set out in what is now chapter 91 of 1 Enoch. Enoch calls upon his children to walk in and practice righteousness (v. 3). This is particularly important because of the great wickedness present on the earth in the midst of which Enoch’s children will live their lives (v. 5). The text, as should be clearly based on its date of final composition, is not aimed primarily at antediluvian peoples. The judgment of wickedness in the flood will be succeeded by a second period in which wickedness will rise to a climax, eventually to be answered by a final judgment (v. 6). The initial readers of the text in this form were members of this latter group, living in the latter days. This final judgment includes the resurrection of the dead at which point the righteous will receive eternal life and the wicked go to eternal darkness (92:3-5). Enoch then approaches this theme homiletically along two different lines.

The first of these is the prophecy of weeks. He speaks of the entire history of the cosmos from his birth as a series of ‘weeks,’ though not necessarily to indicate any particular period of time nor to associate that period with a multiple of seven. One unfortunate diversion taken in interpreting the apocalyptic literature within Scripture is the over-literalization of numbers and time periods. Any reasonably reading of 1 Enoch and other Second Temple apocalyptic literature makes it clear that such a literal interpretation is not defensible. Enoch claims to have this knowledge of history from having read the Heavenly Tablets, which represents a tradition found throughout the Ancient Near East most commonly expressed in the English Bible in references to the Book of Life (eg. Luke 10:20; Phil 4:3; Rev 3:5; 13:8; 17:8; 20:12-15). The focus of the weeks is not on the quality of the era represented by that epoch. Rather, it is on a transitional figure or event which arises at the end of that week which then begins the next.

And so, the first week ends with the birth of Enoch, the seventh from Adam, who obviously within the Enochic tradition is a figure of primary transitional importance (1 Enoch 93:3). The second week ends with ‘the First End,’ the flood of Noah in which a man is saved (v. 4). The third week ends with the call of Abraham who is said to become a ‘plant of righteousness’ which grows and blossoms forever (v. 5; cf. Rom 11:16-24). The fourth week ends with the giving of the Torah as a result of ‘visions’ (v. 6). Here the appearance of Yahweh, the God of Israel, to Moses is considered of at least equal significance to the written text itself. At the end of the fifth week, the temple is built (v. 7). In the sixth week, Israel falls into apostasy, a man ascends to heaven (Elijah), and at the end, the temple is burned to the ground, and ‘the whole race of the chosen root’ is scattered in exile (v. 8).

The seventh week, then, is the period of time during which what would be the Book of Enoch was compiled. This period is marked by the rise of ‘an apostate generation’ all of whose deeds are apostasy (v. 9, cf. Matt 11:16; 12:41-45; 16:4; 23:26; 24:34; Mark 8:12, 38; 13:30; Luke 7:31; 11:29-32, 50-51; 16:8; 17:25; 21:32; Acts 2:40). At the end of this week, the Messiah appears (1 Enoch 93:10). The great increase in evil will be met by the end of God’s longsuffering and the revelation of his wrath (91:7; cf. Rom 1:18). There are two primary effects of this coming of the Messiah for the coming week. First, the nations give up their idols and the gods of the nations are case down and hurled into the fire of eternal punishment (1 Enoch 91:9). It also represents the beginning of the resurrection of the dead, who upon their resurrection receive Wisdom (v. 10).

The period following this, the eighth week, is the age of righteousness (v. 12; cf. Rom 1-5). This is described as a period of spiritual warfare, a battle against sin. At the end of the week, those who practice righteousness receive houses within the house of the Great King in Glory (1 Enoch 91:13; cf. John 14:2-3). In the ninth week, the entire earth will be judged and sin will be put away forever (1 Enoch 91:14). In the tenth, the heavens are judged, with judgment being executed against the Watchers and the other rebellious powers of heaven (v. 15). In the ninth week, the earth passes away and is reborn, in the tenth the heavens pass away and are replaced by a new and eternal heaven of purity (v. 16; cf. Matt 24:35; Luke 21:33; 2 Pet 3:13; Rev 21:1). After this follow weeks without end (1 Enoch 91:17). The separation by an age of the coming of the Messiah from the final judgment is an important feature of Second Temple apocalyptic even outside of explicitly Christian contexts. In light of these ages to come, Enoch exhorts his children to walk through whatever their time is in righteousness (v. 18-19).

The second homiletical approach taken by Enoch is laying out a series of woes that will come upon sinners as the day of judgment approaches for them (94:6-100:13). These woes are not merely condemnations of the world outside of the Enochic community, but rather are proclaimed to the community as a series of warnings not to be misled by the evil practices of the world in which they live their daily lives. In form and function, these woes parallel those of St. Luke’s Gospel (6:24-26; cf. Matt 11:21; 18:7; 23:13-36; 26:24) and St. John’s Apocalypse (8:13; 9-11; 12:12). As in the case of St. Luke’s Gospel, many of Enoch’s woes relate to wealth and influence, Mammon, as a false god (94:7-8; 96:4-6, 8; 97:8-10; 98:2, 11). Beyond this recurring theme, a wide range of sins are described from blasphemy to bearing false witness, to persecution, or even taking vengeance. Judgment is here everywhere described as the scales of justice being balanced and the wicked receiving their own wicked deeds upon themselves and so suffering loss.

Enoch goes on to describe how violence will fill the whole earth and then the judgment itself, at which the blood will run up to the chest of horses (100:3; cf. Rev 14:20). In the midst of this judgment, however, the righteous have two causes to take comfort. First, God will assign a guardian angel to protect each one of the righteous from the wickedness of the world (1 Enoch 100:5). These angels bear witness to the deeds of the wicked against their charges in heaven (100:10; cf. Matt 18:10). Secondly, they will participate in the resurrection, no matter how long they lie asleep in the grave, even if that be a very long time (1 Enoch 100:5).

In chapters 101 and 102, Enoch invokes the awe of the created order and from it argues for greater awe, fear, and reverence for its Creator expressed through obedience. He then describes the fate of the righteous and the wicked during the period in which they sleep in the grave, before the resurrection. Those who have dived in righteousness will have their souls live before God until the time comes for them to awaken (103:4). Those who die in their sin, though the world may think them to have been blessed in life, will have their souls go down into Sheol and thence into chains, burning flames, and the Great Judgment which will last for all generations forever (v. 5-8). Though the righteous suffer many things in this life, they are not forgotten. The angels of heaven ever intercede for them and their names are written in the Tablets of Heaven (104:1). The text of 1 Enoch proper then ends with a command not to alter or change or add to Enoch’s writings nor believe those who do (104:10-11; cf. Rev 22:18-19).

As previously mentioned, in some versions of the text of 1 Enoch, further material is appended to the end. In some cases, this is broken off as an appendix. In other cases, it is incorporated as chapters 105:3-108. In some cases, it is incorporated as additional verses of chapter 105. This material is clearly of a different origin than the Epistle of Enoch and does not continue the flow of that text. It represents a particular Noah tradition found in other Second Temple texts regarding Noah’s birth and nature. These traditions surround Noah as having a unique birth. This unique birth then raises the question of whether Noah himself is, in fact, one of the Nephilim by birth, albeit one whose ways were righteous. There are variations on all of these details within the various surviving written expressions of these traditions. These traditions seem to serve two functions vis a vis the text of Genesis. First, it serves to answer the question of the re-emergence of the Nephilim and giant clans after the flood which was sent to destroy them all within the narrative of the Old Testament. Second, it interprets Noah’s being righteous within his generation not as a temporal generation but as a race (Gen 6:9). This allows the idea of the corruption of the whole earth, save Noah, by these Nephilim to be read quite literally.

In the particular version of the story appended to 1 Enoch, Noah, at his birth, has white woolen hair, bright skin, he speaks, and light shines from his eyes (105:2). His father Lamech panics, thinking him to not be human, a being of a different nature, and the offspring of one of the angels of heaven (v. 3-4). He brings that concern to Methuselah, his father, to find out the truth. Methuselah goes on a pilgrimage to a place from which he can pray to Enoch, his own grandfather, in the heavens to inquire of God through him (v. 6-7). Through Enoch, God reveals to Methuselah that Noah and his three sons would be the means through which humanity would survive the coming judgment of the flood and that he was, in fact, Lamech’s son (v. 12-15; 17-19). He adds, however, that Noah’s progeny will also eventually beget giants upon the earth like those who troubled the earth at that time (v. 16). Finally, he gives Methuselah a book, once again reiterating the fate of the righteous and the wicked as previously described in 1 Enoch, and with a final benediction.

The Book of Enoch, then, is not a single work of a single genre. Rather, it is a collection of ancient apocalyptic traditions transmitted for some centuries orally, then as independent written documents, and finally as one collected text. Outside of Ethiopia and Eritrea, 1 Enoch is not canonical, it is not read publicly in the worship of the Church. On the other hand, as has been seen throughout this series, these traditions and their written form in 1 Enoch has shaped major portions of the New Testament, such as St. Matthew’s Gospel, the Johannine corpus, the Petrine epistles, and Jude. It is best seen, then, as St. Nikephoros I, Patriarch of Constantinople stated in the 9th century, as an apostolic apocryphon. It can be described as “hidden” because it is not read publicly. It is, however, apostolic because it represents in written form traditions which formed a part of the apostolic teaching, as attested by St. Irenaeus of Lyons and others directly connected to that preaching by chronology and spiritual fatherhood. It is a vital part of the tradition in which the Scriptures, particularly the New Testament, were formed. It is a vital part of the tradition in which the Scriptures were passed on to the fathers. First Enoch can, therefore, be a vital part of our own understanding of the Scriptures in their original context and world.

A word of thanks for all the effort you make to share your knowledge of this trove of important Second Temple Era writing. It often gives a new dimension to our prayers and participation in the Divine Services.

Our first introduction to Enoch was reading “The Holy Angels” by Mother Alexandra, some thirty years ago. We were so interested that my wife and I read Enoch and some other works of the Era out loud to one another during a roadtrip. The texts we had (and still do) came from the “Lost Books of the Bible and the Forgotten Books of Eden” translations.

Between your blog, and the footnotes from some of Archbishop Alexander’s essays, we have since used the Internet to find other translations of Enochian and loosely related texts from this period. Thanks again.

Excellent summary Stephen, any view of the apocalypse ought to take into consideration and filter motif’s from and through the enochan tradition.

Regarding our chat on the Remnant Radio show the other week, here is a link to the Jason Staple article on “what do the gentile’s have to do with ‘all Israel’ in Romans 11:25-27”: http://www.jasonstaples.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Staples-All-Israel-JBL.pdf

Would love your thoughts on this, and also, I recently was recommended a podcast called “the apocalyptic Gospel” which bases their views heavily on 2nd temple tradition and a strong view of “all israel” maintaining some level of ethnic, corporate salvation at the end times (something I struggle with). The past 2 episodes on “Acts 1 and 2” display their cards quite clearly, that they believe the “kingdom is not really here” while giving a slight nod to “perhaps it is here in a very spiritual sense but nothing more”….I like a lot of what they say and appreciate their views on 2nd temple material, but I feel they are taking it too far and reading into the text what they think makes the most sense based on their understanding of a 1st century jewish perspective. It is my current belief that the disciples and apostles very much experienced confusion and a lack of understanding, and that Jesus appearing to them after resurrection and “breaking of bread” opened their eyes in many ways, then the coming of the fire of the holy spirit at pentecost opened their minds in new ways, and then as they studied the scripture (and critically the Apostle Paul in his 3 years studying) they began to formulate their understanding and theology of the “gathering of the nations” through the seed of Abraham….If you have a chance to listen to one of their introductory episodes and then skip to the most recent views on Acts, I would great appreciate your perspective.

Hello Father Stephen

Thank you for these educational series. I am a new reader to your blog and am very grateful you make this effort.

Would you have a recommendation for a scholarly edition of the Books of Enoch? Are there fairly recent editions with notes and cross referencing?

This is the best one you can find (it’s also recommended by Fr. Stephen): the two-volume set by Charlesworth. An up-to-date, readable translation, copious amounts of footnotes, and introductory material. https://www.amazon.com/Old-Testament-Pseudepigrapha-set/dp/1598564897