What is now the first section of the Book of Enoch or 1 Enoch, comprised of the first 36 chapters, is known as the Book of the Watchers. There is not only internal evidence that this and the other portions of what is now 1 Enoch were originally separate documents recording internal traditions, but there is clear manuscript evidence that the Book of the Watchers circulated independently in Greek. The text of this portion of the Book of Enoch is known in Ethiopic, as the rest of the book, as well as through Greek fragments. Additionally, the text was found in both Greek and Aramaic among the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran. This variety of textual evidence allows us to have a high level of confidence about the reading of the text itself and its history. Minimally, this text dates back to the third century BC. The Book of the Watchers is likely the most well-known part of 1 Enoch in the contemporary world at least in the broad strokes of its content. The central portion of the text concerns the rebellion of the Watchers, a group of angelic beings, in consorting with human women and bringing forth the giants, the Nephilim. Less well known are the details and the remainder of the text which concerns the Day of the Lord and Enoch’s tour of cosmic geography.

What is now the first section of the Book of Enoch or 1 Enoch, comprised of the first 36 chapters, is known as the Book of the Watchers. There is not only internal evidence that this and the other portions of what is now 1 Enoch were originally separate documents recording internal traditions, but there is clear manuscript evidence that the Book of the Watchers circulated independently in Greek. The text of this portion of the Book of Enoch is known in Ethiopic, as the rest of the book, as well as through Greek fragments. Additionally, the text was found in both Greek and Aramaic among the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran. This variety of textual evidence allows us to have a high level of confidence about the reading of the text itself and its history. Minimally, this text dates back to the third century BC. The Book of the Watchers is likely the most well-known part of 1 Enoch in the contemporary world at least in the broad strokes of its content. The central portion of the text concerns the rebellion of the Watchers, a group of angelic beings, in consorting with human women and bringing forth the giants, the Nephilim. Less well known are the details and the remainder of the text which concerns the Day of the Lord and Enoch’s tour of cosmic geography.

The term “Watchers” to describe a group of angelic beings is attested outside of the Book of the Watchers proper. The term is used to describe “one of the holy ones” three times in the book of Daniel associated with Nebuchadnezzar’s dream that he would be struck mad and live like an animal for a time until he accepted Yahweh as God Most High (Dan 4:13, 17, 23). This affliction is said to be both the decree of the Most High (v. 24) and the decree of the Watchers (v. 17) as a way of referring to the divine council surrounding Yahweh’s throne. The term occurs throughout the Enochic literature, as well as in texts such as the Damascus Document (2:18). Philo of Byblos describes a class of celestial intelligences called “sope shenayim“, the Watchers of Heaven (cited by Eusebius, Prep. Evang. 1.10.1-2). The designation of “Watcher” likely indicates a role for these beings similar to our conception of guardian angels. These beings were assigned to guard and protect humanity and instead turned to the corruption of humanity.

The introduction to the Book of the Watchers and to 1 Enoch as a whole introduces the speaker as Enoch and identifies the contents as the contents of the visions which Enoch received after his translation from earth to heaven. He is writing these things not for “this generation” but for one that is far distant (1:2). This stands in contrast to the visions of St. John’s Apocalypse which are things which will soon happen (Rev 1:1). It should not be assumed from this, however, that this means that this is an eschatological work from our perspective as the original readers of the written text of Enoch were living millennia after Enoch himself would have had these visions. While the Book of the Watchers concerns events already ancient by the time it was put into written form, it is not written to and for those who experienced those events, but for the generation to which the text came.

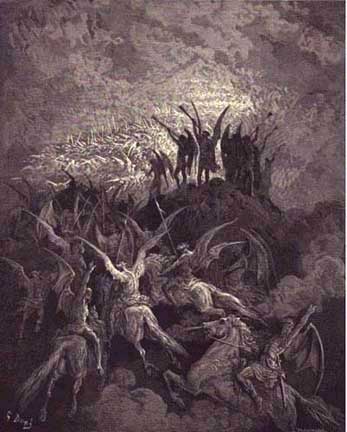

The body of the first five chapters constitutes a midrashic commentary on Deuteronomy 33 describing the Day of the Lord, the Day of Judgment. God appears with his angelic army to execute judgment, setting all things right (cf. Matt 25:31-32). Mountains melt away like wax before the fire and valleys are lifted up (1:6). The wicked are destroyed and the righteous are vindicated (v. 8-9). Enoch 1:9 is cited by St. Jude in his own description of the coming judgment and the Day of the Lord (Jude 14-15). Chapters 2-5 which are rather exceptionally short argue for the just condemnation of the wicked of the whole earth not based on the commandments of the Torah, which of course did not yet exist in Enoch’s day and were given only to Israel, but based on the testimony of every aspect of nature. This includes the stars, the seasons, the animal and even plant creation. This understanding of the accountability of all of humanity due to the revelation of God in the creation is further elaborated in several places, possibly most notably by St. Paul in Romans 1 and 10:14-18. The condemnation concludes, after narrating the created order, with the statement that nonetheless humanity has not kept God’s commandments (Enoch 5:4). This understanding is implied by St. Paul’s understanding of individuals from the nations who kept the commandments apart from knowledge of the Torah (Rom 2:12-16).

After this midrashic introduction, the text proper begins in chapter 6. At this point, Enoch is still not introduced as the narrative protagonist. The following six chapters represent an elaboration of Genesis 6:1-4. Preserved here is the background of the Genesis text in stories such as that of the Mesopotamian apkallu. Rather, the story of the Watchers’ fall is narrated in the third person by no particular speaker. A group of 200 Watchers is called together at Mt. Hermon in order to hatch a plan together. This group is divided into regiments of 10, each with a leader. The leader of all of the 200 is named in Aramaic Shemihazah. In the same sections, the leader is named Asael/Azazel who seems to be a separate figure from the 200 who brings them together and lays out his plot. This plot is that, rather than protecting and aiding humanity in finding repentance and a return to God, they will seek to corrupt humanity. This corruption begins with sexual immorality in a ritual context, the drinking of blood, the sacrifice of animals to demonic beings, and ultimately human sacrifice and the concomitant cannibalism (Enoch 7:3-6). The offspring of this corruption were the giants, the Nephilim, who came to dominate and enslave humanity and force them to serve them (v. 3). Further, in parallel with the genealogy of Cain in Genesis 4:17-24, the fallen Watchers teach humanity secret knowledge for which they are not prepared involving the weapons of war, means of seduction and immorality, sorcery and divination (Enoch 8:1-3).

This tradition as recorded in the Book of the Watchers is fully taken on board by the early Christian Church. St. Irenaeus of Lyons summarizes it in some detail and identifies it as the apostolic teaching regarding the origin of sin and corruption in the world (Apostolic Preaching 18). While in modern times it is generally thought that there was some sort of angelic fall led by the devil in some primordial pre-creation era, this idea comes not from Scripture or the fathers but from puritan poet John Milton. While the text of Enoch itself did not continue to carry authority in much of the Orthodox Church beyond the 3rd century AD, this tradition was accepted and continues to be referenced in various ways even by later authors who rejected its interpretation of Genesis 6:1-4 in particular (eg. St. Augustine in City of God).

In response to these horrors and demonic oppression, the people of the earth cry out and their cries are received by four of the seven archangels who stand before the throne of God (chapters 9-11). These cries are said to be addressed to the holy ones, to the gates of heaven, and to God himself (9:1-2). Ultimately, of course, these pleas are addressed to God of Israel, but their address to heaven, to the throne, and to the holy ones of God’s divine council is not seen to be at odds with this understanding. Clearly communicated here is the understanding the prayers and petitions to God himself can pass through heavenly intermediaries. This practice is referenced also in Job when he is asked to which of the holy ones he will address his plea to Yahweh the God of Israel (Job 5:1). The Apocalypse of St. John likewise presents angels bringing the prayers of the saints before the throne of God (Rev 5:8; 8:4).

This is precisely what the archangels then do, bringing these petitions to the God of gods, Lord of lords, King of kings, and God of the ages (9:4). In response, the Most High gives assignments to each of the four archangels showing that the intermediation goes both ways, responding to prayers through these same heavenly beings through which Yahweh governs creation. Sariel is sent to Noah to give him instructions regarding the coming of the flood. Raphael is commissioned to deal with Azazel, binding him hand and foot, burying him in a ravine to dwell in darkness until the judgment when he will be thrown into the fire. Azazel is not coincidentally the name of the demonic figure to whom sins are sent in the Day of Atonement ritual as practiced in Israel. Raphael’s mission is one of atonement in the aspect of both goats used in that ritual. He is commanded to write all of the sins of the world over Azazel (10:8). He is also instructed to heal and purify the world from the corruption which Azazel has caused (v. 7). First Enoch 10:8 reads, “The whole world was made desolate by the works of the teaching of Azazel. To him ascribe all sins.” In describing the eschatological atonement of Christ, St. John borrows this language (1 John 3:8; 5:19).

The Archangel Gabriel is assigned to destroy the Nephilim, the giants. He does not do so directly, but by pitting them against each other in wars until they are destroyed by the flood (10:9-10). Michael is sent to capture and bind Shemihazah and the other sinful watchers and bind them, imprisoning them in the abyss until the Day of the Lord when they will be judged. The binding of the rebellious Watchers by St. Michael and their imprisonment is referenced in both 2 Peter 2:4-5 and Jude 6. Yahweh, the God of Israel then goes on to describe the age to come which will result when all sin and uncleanness has been cleansed from the earth in eschatological atonement of which these angelic missions is the beginning (Enoch 10:16-11:2).

This description is cited by St. Irenaeus in his description of the Messianic age in an interesting way. St. Irenaeus says that those who knew St. John the apostle say that he taught that Christ said that the age to come would be one of abundance described in terms of abundance of food mimicking the language of 1 Enoch 10:19. Most readers of St. Irenaeus have assumed that this is St. Irenaeus recording some previously unknown saying of Jesus which he has heard secondhand through St. Polycarp. Modern interpreters have seen this as St. Irenaeus taking a chiliastic position of an earthly kingdom. The speaker, however, in 1 Enoch 10:19 is the Lord. It is far more likely, then, that given St. Irenaeus’ authoritative use of the Book of Enoch elsewhere, he is here saying that St. John cited 1 Enoch 10:19 Christologically. St. John saw the speaker here to the Archangels as God the Son. This way of reading Old Testament texts is ubiquitous in the fathers, but it is missed here because of the presupposition that 1 Enoch is not Scripture.

The beginning of chapter 12 shifts to presenting Enoch as the protagonist of the remainder of the Book of the Watchers. In chapters 12-16, the Watchers plead with Enoch to request mercy for themselves and their children, the giants, from God. They are not repentant, nor certainly are their progeny, but they want a diminishment of punishment. Enoch travels to the area around Dan and Mt. Hermon, both associated with the evil and corruption of the Nephilim, and from there he accesses their prison. He brings their play before the God of Israel and is told in no uncertain terms that due to their continued rebellion and wickedness there will be no mercy and their punishment will be eternal. The somewhat cryptic reference in 1 Peter to Christ’s proclamation to those imprisoned from the days of Noah in Hades is a reference to Christ fulfilling this pattern from 1 Enoch (1 Pet 3:18-20). The gospel is the preaching of Christ’s victory over the demonic powers, sin, and death. Christ proclaimed this victory to the imprisoned fallen angels to proclaim their doom as Enoch had, though now that doom was fulfilled.

In the midst of this condemnation, the spirits of the giants which have come forth from them at their deaths are described as continuing to roam the earth to afflict man (1 Enoch 15:8-16:1). This is the understanding of the origin of unclean spirits in the Old Testament and demons in the Synoptic Gospels presupposed by those narratives. The condemnation also contains a statement from God that he did not create women among the spirits of heaven, in contrast to the creation of woman from Adam among humanity (15:6-7) This is echoed in Christ’s statement that angels are neither married nor given in marriage (Matt 22:30; Mark 12:25).

The remainder of the Book of the Watchers, chapters 17-36 is the description of Enoch’s journey with the seven archangels through the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. It is a gazetteer of cosmic geography. Crucially, Enoch journeys to the north, south, east, and west with the underworld and the heavens overlapping with the geography of the earth. Chapters 17-19 give a brief summary of the entire journey while the following chapters then break down the journey through the cosmos in greater detail.

First Enoch 20 begins with a listing of the seven archangels. The number of the archangels as seven is referred to by St. Raphael in Tobit 12:15. These seven spirits who stand before the throne of God are also referenced in St. John’s Apocalypse (Rev 1:4). The first listed is Uriel, a very prominent archangel in Second Temple literature, mentioned in Scripture only in 4 Ezra/2 Esdras. Next is Raphael who is listed as in charge of the spirits of men and who figures prominently in the book of Tobit. Reuel is described as taking vengeance on the stars meaning that he is responsible for the discipline of other angelic beings. St. Michael is said to have been placed in charge of Israel, the elect. St. Gabriel is said to be in charge of paradise as well as the “serpents and the cherubim.” “Serpents” here is a reference to seraphim. Remiel is said to be the angel in charge of raising the dead, likely a reference to shepherding departed spirits to their destination. Finally, Sariel, elsewhere called Samael, is said to be in charge of the spirits who sin against the Spirit.

These seven spirits serve as guides on Enoch’s tour. Uriel, who is said to be in charge of Tartarus, shows Enoch and describes the place where the fallen stars, the imprisoned Watchers, are chained until the End of Days (1 Enoch 21:1-10). Nearby in the underworld, Enoch sees the mountain of the dead, which is Sheol or Hades. The spirits of the dead are brought to the mountain to dwell in caves hewn out from the rock. St. Raphael describes the caves as being for the righteous dead, the unrepentantly wicked dead, the martyrs, and those who died apart from the truth of God respectively (22:9-13). The righteous will someday be set free. The martyrs will receive justice and salvation. The unrepentant wicked will be condemned to perish for all generations with the fallen angelic beings. The final group who died apart from truth will remain in Hades where they are forever. Enoch sees two further details. The souls of the righteous, though in Hades with the rest, have a spring of refreshing water with them as they await the coming of the Lord (22:2, 9). Outside of the cave of the martyrs, one spirit, whom Raphael identifies as Abel, is leading the others in crying out for justice (22:6-7). This tradition, an interpretation of the crying out of Abel’s blood, his life, from the earth (Gen 4:10), is attested to multiple times in the New Testament (Matt 23:35; Heb 12:24; Rev 6:9).

In chapters 24 and 25, Enoch sees the mountain of God atop which sits his judgment seat upon which he will sit to render the final judgment at the End of Days. They then travel to the center of the Earth, where sit Zion and Jerusalem (26:1-6). This is early written documentation of the tradition that Jerusalem is the “navel of the world” and stands at its center. Christ’s crucifixion there is therefore taken to represent salvation wrought in the middle point of the earth (Ps 74:12). Next to the holy city is the Valley of Hinnom, Gehenna, which will be the eternal abode of the unrepentant wicked after the final judgment while the righteous and the martyrs will dwell in that holy city, the new Jerusalem (1 Enoch 27:1-4). It is Sariel who describes what he will do with the wicked on that day. In the midst of the New Jerusalem sits the tree of life, from which all will eat in the age to come (26:3. cf. Rev 22:1-2).

Finally, Enoch is taken to see Paradise, which St. Gabriel describes to him as the place from which his father and mother of old were exiled (32:6). The trees and beauty of Paradise are described in great detail, but it has, as Enoch sees it, no residents (28:1-32:2). It is described, however, as the Paradise of the righteous indicating that this is a place to which the righteous whom he saw before in the watered cave of Hades will someday be brought. This finds its fulfillment in the Harrowing of Hades in Christ’s descent, as alluded to by St. Peter. Within Paradise, Enoch sees that the “tree of wisdom” still stands (32:3-5). It is reaffirmed here that it is not that the tree itself is a wicked or evil thing but that like the knowledge given by the Watchers, it was knowledge not to be seized by man but rather given by God at the proper time.

The Book of the Watchers concludes with Enoch visiting the very ends of the earth and seeing all of the visible and invisible creatures of God in chapter 33. The last three chapters offer another summary and the obeyed command for Enoch to record what he had seen in the text now being read. It ends in such a way that the independent nature of this portion of the text is re-emphasized.

The Book of the Watchers, therefore, not only records the traditions for which it is famous, concerning the Watchers, the Nephilim, and the flood. It also describes the spiritual geography of the entire creation in a way that is presupposed by the New Testament writers and the fathers in their understanding of events within the invisible creation, the spiritual world. Further, it describes how these spiritual locations overlay visible creation. The Book of the Watchers sets the table for the coming of the Christ, the Messiah. The Son of Man who is to come and fulfill all things will be the subject of the next section of 1 Enoch to be discussed, the Book of Parables.

Another fine commentary. Do any liturgical texts that we use have any direct or indirect quotes from Enoch? I’m assuming the Ethopians must. These posts would make a great book Father. Do you have any books coming out?

Thanks

I am enjoying the posts very much. I’ve been in a lot of this literature myself. And my personal views are that 1 Enoch is very important, and obviously highly influential on the Christ and the Apostles.

This was such a great article! Being raised protestant without the Book of Enoch it is so wonderful to be introduced to these traditions. I still wonder if these apocryphal books should be taken literally as I assume St. Irenaeus did. Does the Church has a firm stance on this?

Wow!

Thank you for the overview on the Book of Watchers father – it was very well done. It does raise a question for me though. Given how influential the Book of Watchers seems to be on the NT writers and the early Church fathers, how are we supposed to view the book?

I come from a Protestant background which may be the cause of my confusion. So I may be misunderstanding, but it seems as if you’ve made the case that 1 Enoch is assumed as a true narrative by NT writers/early Church fathers. Is this the case and should I be viewing it that way? If not, how should I view it?

I apologize this may be a way deeper question then you might want answer in a quick comment, but any little tid bit helps!

In Christ,

Colt

I think part of this may be that canonicity in Protestant theology, and really in the West as a whole, is seen in binary terms. Either it is canonical or it’s not. And if it’s not, it’s automatically substantively untrue. But in reality, that’s not how canon was developed or understood in the early Church or ever in the East. So, there is a classification of books considered ‘canonical’ which is to be read publicly in worship. This was settled in the case of the New Testament (except for Revelation) by a unified tradition by the end of the second century. It was never really settled vis a vis the Old Testament and different Orthodox churches disagree about a handful of Old Testament books. But again, this is a question of what is to be read publicly and liturgically. There is then a second category of things that should be read by Christians outside of public worship. So this would clearly include, for example, the church fathers’ writings beginning with the apostolic fathers. They aren’t Scripture, but they contain truth and hold a level of authority. Then there’s a third category of things that shouldn’t be read, generally because they are heretical. For the fathers and through the Orthodox tradition, a large body of Second Temple literature has been included in that middle category, not read in liturgy but preserved by and for the faithful. In modern English-speaking Orthodoxy, we’re mostly disconnected from that. That’s a big part of what I’m working to correct here.

Even within the Scriptures we observe a certain hierarchy. Before the formation of the NT, the Torah held a place of pre-eminence, followed by the Psalms and Prophets, then the other writings. Likewise, you can see in our worship the pride of place of the Gospels, then the rest of the NT, then the OT.

Thank you for this succinct overview of the hierarchy of texts from the Orthodox perspective. I’ve been Orthodox for 20 years, come December 3rd, and it’s still just a little too easy to fall into that old binary way of seeing canon where texts are concerned. I was just introduced to this by our former assistant priest earlier this year in a class on spiritual warfare and have become quite interested in learning more. I’ve ordered the 2-volume OT Pseudepigrapha (Charlesworth), and look forward to learning more from your posts.

Does Enoch depict a spherical Earth or a flat Earth cosmology?

First Enoch is working from the standard OT/ANE cosmology where the dry land is sort of like a table supported by pillars with water around and beneath The underworld is within the table and the abyss beneath. The heavens are like a dome with the dwelling place of God atop the dome. So, the cosmos is sort of a big sphere made up of a series of concentric spheres, bisected by the earth’s surface. This is spiritual geography that overlaps with the visible and physical.

When the angels declare their rebellion, 1 Enoch tells us:

But they all responded to him, “Let us all swear an oath and bind everyone among us by a curse not to abandon this suggestion but to do the deed.” Then they all swore together and bound one another by the curse. And they were altogether two hundred; and they descended into Ardos, which is the summit of Hermon.

One of the things that is taught about rebellious spiritual powers is that a) being spiritual and not corporeal beings (and therefore “changeless” within time) they cannot repent—that it’s the flesh and the possibility of death that allows repentance (cf: The Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith) and b) that when they cast their lot with Satan and against God, they did so knowing the eternal consequences of their actions. This second part seems to be what 1 Enoch 6:3-6 is saying. They’re rebelling and cursing themselves knowing full well what that curse entails? How does Mt Hermon fit into the physical-spiritual landscape? (I’m thinking of your piece on the geography of the underworld.) Is Mt Hermon chosen because of the pagan worship that happens here? Or is Baal/Pan/etc. worshipped here because of the rebellion beginning here?

The entire area around Mt. Hermon, Bashan, Dan, is associated with gateways to the underworld as far back into literature (i.e. Ugaritic sources) as we have record. Paneas/Baneas was considered to be such a gateway to Sheol/Hades at the base of Mt. Hermon for as long as we have record, that’s why the Baal and Pan shrines developed there. Mt. Hermon is covered with pagan temples however. The tombs of the Rephaim are just on the other side of the mountain. And of course, Mt. Hermon literally means, “The cursed mountain.” First Enoch uses the oath of the Watchers as the origin of that name. But the area continues to be associated with evil well into the New Testament. See for example Matt 4:12-17. There’s a reason Christ begins his mission in Galilee.

Fascinating article, Father! We in the modern, Western world definitely need to be taught the many intricacies and nuances of “canonicity” of Tradition, both Jewish and Christian.

Would you recommend a particular publication of the Book of Enoch for us? Thanks!