One figure from Christian tradition who has certainly entered into contemporary popular culture is that of the antichrist. Though this has primarily been through the medium of horror fiction, even that fiction represents a newer iteration of themes in art and popular speculation that go back through the medieval period in the West in particular. In addition to this imagery, there have been, since before even the Protestant Reformation, again primarily in the West, continuous attempts to try to match information derived from passages in the Scriptures which speak of the last days and current events. These include attempts to identify some living person as the antichrist. There are three primary passages within the New Testament which speak of this antichrist figure. Of these, two are vague in their details and the third is apocalyptic literature meaning that it is rich with symbolism. The primary reason for this lack of clarity is that the authors, in this case, Ss. Paul and John, are referring to pre-existing traditions within the Second Temple period regarding the coming of an anti-Messiah along with the Messiah against whom the latter will make war. The central theme of the New Testament is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah with all that that entails. These anti-Messiah or antichrist texts, then, are pointing to how that element of messianic prophecy will ultimately be fulfilled.

One figure from Christian tradition who has certainly entered into contemporary popular culture is that of the antichrist. Though this has primarily been through the medium of horror fiction, even that fiction represents a newer iteration of themes in art and popular speculation that go back through the medieval period in the West in particular. In addition to this imagery, there have been, since before even the Protestant Reformation, again primarily in the West, continuous attempts to try to match information derived from passages in the Scriptures which speak of the last days and current events. These include attempts to identify some living person as the antichrist. There are three primary passages within the New Testament which speak of this antichrist figure. Of these, two are vague in their details and the third is apocalyptic literature meaning that it is rich with symbolism. The primary reason for this lack of clarity is that the authors, in this case, Ss. Paul and John, are referring to pre-existing traditions within the Second Temple period regarding the coming of an anti-Messiah along with the Messiah against whom the latter will make war. The central theme of the New Testament is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah with all that that entails. These anti-Messiah or antichrist texts, then, are pointing to how that element of messianic prophecy will ultimately be fulfilled.

Though many contemporary discussions of the antichrist figure move immediately to the beasts of Revelation, the most critical text in all regards is actually the second chapters of St. Paul’s Second Epistle to the Thessalonians. In his first canonical letter to Thessalonica, St. Paul had had to clarify certain things regarding the glorious appearing of Christ and the resurrection of the dead. In this text, St. Paul is offering further clarification in the opposite direction. In the first epistle, St. Paul answers the concerns of those who might believe that because their loved ones had died before the parousia of Christ, they somehow ‘missed out’ on that event and the life of the age to come. Here, St. Paul corrects the opposite error, that the community had somehow missed out because these events had already unfolded or were currently unfolding and they were not a part (2 Thess 2:1-2). Apparently, the apostle even thought it a possibility that someone teaching such a thing might counterfeit letters from him to support their teaching.

St. Paul’s response to this error is not to say that the day of the Lord is far off in the future and shouldn’t be a subject of interest or concern. Rather, he points to certain signs that will come first that will indicate that the day of the Lord is coming upon the whole creation. The first, mentioned only briefly, is an apostasy (apostasia, v. 3). While this is sometimes translated into English as rebellion and based on that English translation associated with the Jewish revolts, its meaning is clear in the context of the chapter. The Greek here refers to leaving a place in which one formerly stood. Its primary use in wider Greek literature is as a word for ‘desertion’. St. Paul contrasts this event, in which many will desert their stand, with a call at the end of the chapter for the community in Thessalonica to stand firm (stekete, from the same root) in the traditions which they have been taught (v. 15). The apostle is clearly, then, referring to a mass defection from the apostolic faith.

This event is directly related to a figure whom St. Paul calls ‘the man of lawlessness’ and ‘the son of perdition’. Though the term ‘antichrist’ does not appear in 2 Thessalonians, the first of these titles used by St. Paul, when taken within the context of his usage of terms, indicates the anti-Messiah figure. Though not made clear in English translation, the ‘man’ in ‘man of lawlessness’ is the Greek ‘anthropos‘. It is not the word for an individual man, but for a human. Nonetheless, ‘the lawless human’ does not really capture St. Paul’s meaning. Another critical place in St. Paul’s writings in which he uses ‘anthropos‘ to refer to a single human male is in Romans 5:12, 15. Here, both Adam and Christ in the contrast drawn by St. Paul are referred to as one ‘anthropos‘. The apostle uses this term for ‘man’ because he intends each to be seen as archetypal. There is a relationship between each and the entirety of humanity. The same is true in 2 Thessalonians 2:3. The lawlessness (anomia) of this man is connected to the lawlessness of all humanity.

St. John points out that all sin is lawlessness (1 John 3:4). The contrast of Romans 5 is between Adam as the bringer of death and Christ as the bringer of life. Here, the contrast is between ‘the man of lawlessness’ as the archetypal sinner on one hand and Christ as the destroyer of sin with the Holy Spirit as sanctifier on the other. The use of ‘lawlessness’ here, rather than calling him the ‘man of sin’ is important in connecting this figure to preceding anti-Messiah traditions. From at least the third century BC, literature regarding the Messiah from the Enochic traditions to the Dead Sea Scrolls, in particular, began to refer to his primary opponents as Belial or the son of Belial. St. Paul clearly has received this tradition of Belial as a devil figure as evidenced by his question, “What harmony is there between Christ and Belial?” (2 Cor 6:15). The apostle goes on to extend the contrast to ‘the faithful’ and ‘the faithless’ in a way that parallels the usage of the name in the book of Jubilees which calls uncircumcised Gentiles the ‘sons of Belial’ (Jub 15:32). The etymology of Belial is contested, but one option, ‘yokeless’ or ‘Beli ol‘, is supported by the Ascension of Isaiah, a text referenced in Hebrews 11:37, which states, “the angel of lawlessness, who is the ruler of this world, is Belial” (Asc. Is. 2:4). It is at least likely if not certain then that St. Paul is using the Greek ‘anthropos tes anomias‘ in place of the Hebrew ‘adam belial‘, or ‘man of Belial’ in Proverbs 6:12-15.

The second title used by St. Paul, ‘the son of perdition’ or ‘son of destruction’ is important to flesh out the way in which the apostle sees the antichrist as archetypal. This title in the plural is used as a title for the Nephilim in Jubilees (10:3). This serves to connect the antichrist as the denouement of human sin, the eschatological archetypal sinner, with the protological archetypal sinner, Cain. The story of Genesis 4-6 is the story of a descent of humanity into sin and corruption which culminates with the Nephilim who are demonic humans in their very origin and being. St. Paul’s application of the term does not necessarily indicate that the antichrist will be a latter-day Nephilim but does place him in continuity with these beings of ancient evil. The term ‘giant’ applied to these beings, of course, refers not merely to physical size but carries the meaning of ‘bully’ or ‘tyrant’.

This ancient tradition of ‘god-kings’ as earthly representatives of the fallen spiritual powers is further reinforced by St. Paul when he describes the activity of the ‘son of perdition’. He exalts himself against, and over, everything which is called a god and over every object of piety (2 Thess 2:4). The verse continues that takes his seat in the temple of God. Here, ‘theos‘ occurs with the article and so it is rightly translated with the capital ‘G’. By many interpreters, this has been over-literalized to indicate that he must at some point be physically present in a temple in Jerusalem. While this is possible, the emphasis in the Greek clause is on the fact that he ‘sits’ in God’s house, not on his location. In the ancient world, to sit when in someone’s presence, rather than standing, was to treat that person as an equal or inferior. This is an idiomatic way of stating that he places himself as God’s equal. There is a clearly implied antithesis between the antichrist and St. Paul’s description of Christ in Philippians 2:6. Finally, St. Paul says that he proclaims himself to be a god or to be divine.

The idea of divine kingship, while exemplified in its most wicked state by the Nephilim, was not ancient history for the apostles. Caesar himself, of course, claimed to be divine and the son of a god. When St. John describes the antichrist, then, in the Apocalypse, he casts him as Caesar and one Caesar in particular. The beast of St. John’s vision rises up out of the sea, the realm of chaos, and is a crowned ruler ascribed blasphemous names (Rev 13:1). Caesar’s titles included most of those ascribed to Christ by the New Testament, i.e. savior of the world, son of god, and lord (kyrios). Authority is given to him over every tribe and people and language and nation and he demands worship from them all (v. 6-7). He receives this through conquest and the title ’emperor’, ‘imperator‘, means conqueror.

This description, combined with St. John’s portrayal of the beast as an amalgam of the beasts of Daniel which represented world empires (v. 2; Dan 7:3-7, 17-22), again indicates this general institution of wicked divine kingship. St. John, however, provides two additional details which serve to present a historical person as a sort of ‘exhibit a’ of the type. The first is the number which St. John presents as containing his name (Rev 13:18). While St. Irenaeus of Lyons and a few other fathers see within the number 666 the name ‘Titan’ (Adv. Haer. 5.30; Hippolytus, On the Antichrist, 50.11; Oecumenius, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 158.1), thereby connecting him by one more means to the Nephilim, another possibility seems more likely as St. John’s original intent. By exchanging letters for numbers, the name of Nero Caesar in Hebrew or Aramaic, ‘Nron Qsr’, adds up to 666. Some early manuscripts have 616 as the number instead, which is the value if the second ‘nun’ is dropped from the Hebrew or Aramaic transliteration to mirror the Latin, eg. ‘Nro Qsr’.

What clinches the immediate reference of St. John’s image as that of Nero is his description of the beast as having had an apparently fatal wound that had been healed (Rev 13:3, 12). In the latter half of the first century, there was a widely attested legend that Nero would return from his death, either apparent or actual, somewhere in the East (eg. Dio Chrysostom, Discourse XXI; Sybilline Oracles IV-V; Tacitus, Histories II.8; Suetonius, LVII). Often, this tradition was tied to the region of Asia Minor in which the churches to whom St. John addressed the Apocalypse were located. During this period, several pretenders to the Roman throne appeared claiming to be Nero Redivivus. So tenacious was this belief that at the beginning of the fifth century, as the Western Roman Empire collapsed, it was still believed by Christians and pagans alike as attested by St. Augustine (Civitas Dei XX.19.3). Pagans believed that Nero would return to restore Rome to glory while Christians believed that he would return as the antichrist. This idea of a false, parody resurrection fits also with St. Paul’s description of the antichrist as ‘appearing’, much as Christ will ‘appear’ at his parousia (2 Thess 2:3, 6, 8).

St. John is not saying that the final antichrist figure also described by St. Paul was Nero. Rather, Nero, like Cain and the Nephilim serve as types of the antichrist who is coming. Both St. Paul and St. John see the antichrist proper as the final fruition of a spirit already at work in the world. St. Paul speaks of this as the ‘mystery of lawlessness’ (2 Thess 2:7). St. John says, “You have heard that an antichrist is coming, just as many antichrists have come” (1 John 2:18). He further says, “This is the spirit of the antichrist, who you heard was coming and is not already in the world” (1 John 4:3). These forerunners of antichrist, from Cain throughout history until the antichrist himself is revealed, are all participants in this spirit. St. Paul describes this as the participation of the antichrist and all of his forerunners in the energies (energaia) of Satan (2 Thess 2:9). The ‘mystery of lawlessness’ is such an energy that is already at work in the world (v. 7). These figures are participating in and bringing the works of the devil to fruition in the world (cf. 1 John 3:8-10). St. John uses the imagery of sonship to describe this imagery and presents Cain as the prime example (v. 12). It is a commonplace in Second Temple literature to refer to evildoers, in particular, idolaters and the sexually immoral, as ‘sons of Belial’ (see especially the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs).

St. Paul says that while the mystery of lawlessness is active, the antichrist himself has not been revealed because of a ‘restrainer’, in Greek ‘katechon‘ (v. 7). ‘Restraint’ is not the primary meaning of this Greek word. The more common usage would be something more like ‘occupier’. It is typically used to refer to a garrison or occupying force which holds territory. In the context, however, and in the interpretation of every father who comments upon the passage, it is taken to refer to a ‘restrainer’ who is holding off the coming of the antichrist. These two understandings are not necessarily averse each other. An occupying force or garrison can certainly serve the function of repelling invasion. When St. Paul speaks of the removal of this restrainer, he speaks of it literally ‘departing from the middle’. This ‘restrainer’ then is a sort of border protector who is warding off Belial in the present but will someday depart allowing the powers of evil led by the antichrist to be revealed and conquer.

While it is not typically how we think of it in the contemporary period, the priesthood of Israel was conceived often in Second Temple literature in terms of spiritual warfare. Levi’s first actions in the text of Genesis is his leading of the massacre of the men of Shechem to avenge the rape of his sister (Gen 34:1-27). The Levites proper were not designated as priests until they received the priesthood as a reward after assisting Moses in the slaying of the 3,000 tribal priests who had worshipped the golden calf at which point they took their place (Ex 32:26-29). Phinehas received the priesthood for his descendants after slaying an Israelite man and foreign woman to end a plague upon the entire camp (Num 25:1-13).

This last example, that of Phinehas, involves his literal intervention between his people and the plague. The Levites, when the layout of the Israelite camp is described, camp around the tabernacle at the center so that they, by their more extreme practice of holiness, can serve as a protective buffer between the presence of Yahweh and the people (Num 1:53; 18:5). One particular incident, however, is particularly telling and that is the rebellion of Korah which led to a plague breaking out upon the camp. In response, Aaron took his censer and offered incense standing ‘between the dead and the living’, by which stand he stopped the plague (Num 16:46-48). Later meditations upon this text saw it explicitly in terms of spiritual warfare. Wisdom describes Aaron as having fought using the censer and prayer as his weapons (18:21). He conquered the wrath (v. 22). He beat the wrath back (v. 23). The destroyer yielded to his assault (v. 25). By the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, this imagery had been taken so far as to describe the opponents of the children of darkness in the great final battle as an army of priests led by the high priest Melchizedek (1QM II, 1-3; XV, 4-7; XVI, 13-14).

The central theme of 2 Thessalonians 2 surrounds worship. The coming of the antichrist is part of a great apostasy over against which he calls the Thessalonians to stand. This apostasy is further described as, because of their refusal to believe in the Truth, they are given over to a lie (v. 9-12). This lie is propagated by the antichrist and the delusion into which they fall is one of the energies of Satan. He vaunts himself as divine, as equal to God himself, and demands worship. The restraint against his revelation, against this falling away and apostasy, against the propaganda of the lie of false religion, is true worship and true religion. Specifically, the fulfillment of the offerings of incense and sacrifice in the old covenant by the offering of the Eucharist and incense in the new as spiritual warfare. It is this worship, personified as those who offer it, which stands in the midst but which will depart one day bringing about the end.

It is a commonplace not only in the fathers but in Orthodox tradition to this day to associate the restrainer with the Christian monarchy from St. Constantine to the last of the Russian Tsars. This interpretation is not opposed to that offered above. As people who have come of age with a concept of the separation of church and state, we often fail to realize the religious role of the emperor. Kings in the ancient world were also priests and the primary celebrants of the cult. This included the Roman emperors who bore the title ‘pontifex maximus‘. One primary evidence of the fullness of St. Constantine’s conversion was his disavowal of sacerdotal duties. He did not make himself a Patriarch or high priest within Christianity breaking with all previous Roman tradition. Not only this, but he defunded the public sacrifices to the pagan gods and removed the sacrifices to those gods before going into battle, replacing them with the celebration of the Eucharist by Christian priests and the building of churches throughout the empire precisely for the protection of that empire through spiritual warfare. The Christian monarch, therefore, was the figure who protected and maintained the celebration of the Eucharist in every place which in turn protects and sustains the entire world. His removal has therefore been taken as a sign of the end by Orthodox faithful precisely because it jeopardizes the perpetual celebration of the Eucharist and the offering of Christian prayer.

In 2 Thessalonians 2, St. Paul describes a series of events which will proceed the glorious appearing of our Lord Jesus Christ. Because of the refusal of people to be faithful to the Truth, they will be handed over to following a lie. This lie will be spread by a liar, by the man of lawlessness, the son of perdition, the antichrist. His apostate religion will make war against the faith until Christ himself appears to establish justice upon the earth once and for all, destroying the antichrist by the breath of his mouth (v. 8). Because this is his destiny, the faithful of Thessalonica, and all of the faithful can have both comfort and courage as they stand firm in the apostolic faith which has been handed down to us by our fathers.

Father Stephen,

Filled to overflowing – you’ve answered all of my questions about the antichrist, and more! But it would sure be nice if we would know who the “antichrist proper” will be!

But the ‘restrainer’… ah, so that’s why you mentioned in a previous post that some of our Saints said .”when the Divine Liturgy ceases, the end of the world will come”.

Here, you say: “The restraint…is true worship and true religion. Specifically, the fulfillment of the offerings of incense and sacrifice in the old covenant by the offering of the Eucharist and incense in the new as spiritual warfare. ”

Well, so…the Covid pandemic – the spirit of antichrist, empowered by satanic energies “jeopardizes the perpetual celebration of the Eucharist and the offering of Christian prayer”. He will use any and all devices to prevent our partaking. Anything, including our fears, that will to lead to our destruction.

As St Paul admonishes the Thessalonians to remain faithful to the Truth during these ‘end time’ series of events lest they be “handed over to following a lie”, seems to be quite the message for us today.

Father, thank you for not being shy about calling this what it is – warfare. When we say “Christ conquered”, it is a spiritual battle that was, and is still being, fought. If spiritual warfare is taught rightly, as you do in your work, we can understand it rightly, rather than either being too presumptuous or being fearful of ‘satan behind every bush’.

I do have two questions:

What is the ‘backstory’ of the antichrist’s companion, the false prophet?

And regarding this verse in the parable of the unjust judge (Lk 18:8) “…Nevertheless, when the Son of Man comes, will He really find faith on the earth?” Could it be that Jesus here alludes to the great apostacy?

Thank you very much, Father.

Hi Father,

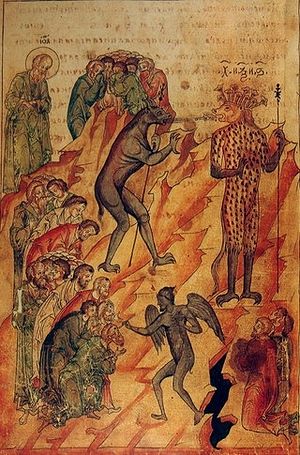

Thank you for another very interesting post. I’m curious as to who or what that leopard-looking figure is in the image above.

This was a revealing commentary of the texts quoted above. I often wonder if the closing of churches would play any part in the advance of the coronavirus we are experiencing now? And the general state of Christians not taking the Liturgy serious as previous generations.

Father Stephen,

Thank you again for the excellent article. Would you say that the Orthodox Christian monarchy is the “earthly” manifestation of Christ’s statement in Matthew 28, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me.”? If so, would that make the Great Commission a type of “military order” against the antichrists that are present in every age?

Hello Father Stephen,

Thank you for this eye-opening piece on the way to understand the meaning of the antichrist. I had never paid too much attention to this concept given that all I heard were mundane comments that fed the human desire to put a name to the antichrist (Nero, Hitler, etc.). It is worrisome that today we appear to not have the “restrainer” that was so important since inception of Christianity until the last Tsar. I do not know if the Pope could be such a restrainer–even if it is from a Western perspective. But it is really scary to see the lawlessness of the human virtues that we see today. I feel lucky that I am Orthodox and see my faith as my anchor and rudder.

Thanks a lot, once again.

So enlightening. So bright.

May God bless you.