This week, most of the contemporary world will celebrate the beginning of a new calendar year. In the ancient world, a variety of calendars were used by different peoples to organize time in a manner held to be sacred. This produced different beginning dates for the annual cycle in addition to years of different lengths and often, as with the modern leap year, periods of time inserted as corrections. In ancient Israel through the Second Temple period, two overlapping calendars are in evidence and both are described in the Torah as well as in the practice of the people throughout the era. Corresponding to these two calendars are two different beginnings for the annual cycle. There were, in essence, for our fathers two different New Year’s Days. Both of these days, further, are reflected in the life of the Orthodox Church though fulfilled in different ways.

This week, most of the contemporary world will celebrate the beginning of a new calendar year. In the ancient world, a variety of calendars were used by different peoples to organize time in a manner held to be sacred. This produced different beginning dates for the annual cycle in addition to years of different lengths and often, as with the modern leap year, periods of time inserted as corrections. In ancient Israel through the Second Temple period, two overlapping calendars are in evidence and both are described in the Torah as well as in the practice of the people throughout the era. Corresponding to these two calendars are two different beginnings for the annual cycle. There were, in essence, for our fathers two different New Year’s Days. Both of these days, further, are reflected in the life of the Orthodox Church though fulfilled in different ways.

Ancient Israel had both a liturgical or ritual calendar and an older, agricultural calendar. The liturgical calendar, at least in its broad strokes, is likely the one most familiar to modern Christians. It divides the annual cycle based on ritual observance and feasts which themselves represent participation in the life of Israel in general and its earliest history in particular. Much can be said about each individual feast of the festal calendar, but in general, the yearly feast brought participants directly into the events of history, placing them within Israel’s story and reaffirming their identity. This calendar is instituted in the Torah beginning with the first event in Israel’s birth as a new people belonging to Yahweh, the Passover. Ritual participation in this event is so important that its contours and its place in the calendar are described before the event itself takes place. “This month will be to you the beginning of months. It will be the first month of the year to you” (Ex 12:3). This month is the month of Nisan. The dating of all of the feasts on the ritual calendar is based on the dating of the Passover. In Rabbinic Judaism, references to this calendar are sometimes shorthanded as ‘Nisan years’.

This calendar cycle finds its fulfillment in the major elements of the Orthodox liturgical calendar which are dated around Pascha as the feast of feasts. This includes not only the Lenten cycle and Holy Week but also the feast of Pentecost. Further, significant portions of the following liturgical cycle, particularly the cycle of readings, are numbered based on the days and weeks following Pentecost. The cycle of feasts from Pascha to Pentecost mirrors the cycle from Passover to Pentecost on the ancient calendar. Though representing the fulfillment of these feasts and the events which they commemorate, they serve the same function in bringing the faithful into direct participation in the events themselves.

Though Passover is likely the most well-known Israelite feast by contemporary people, when asked about the ‘Jewish New Year’, most will not think of the month of Nisan or the Passover but rather Rosh Hashanah. Rosh Hashanah itself means the first or beginning (literally ‘head’) of the year. Its date varies in relationship to the modern civil calendar, but it generally falls within the month of September. Its calendar date, Tishri 1, is roughly six months after the Passover but represents an independent and earlier calendar tradition. Like most of the early calendars of the Ancient Near East, including that of Egypt, it is based in the agricultural cycle which begins with the harvest beginning in September. Rituals aimed at a successful harvest by agrarian peoples naturally gravitate to the period immediately before that harvest begins. That this calendar predates the ritual calendar already described is alluded to repeatedly in the Scriptures, notably in Exodus 23:14-16 which states that the Feast of Tabernacles takes place at the end of the year (August/September). This text in Exodus describes a cycle of three feasts, Unleavened Bread, Firstfruits, and Tabernacles as the festal cycle of the liturgical calendar. Leviticus reiterates this cycle (Lev 23:2-22) but then goes on to describe a cycle of feasts, including, for example, the Day of Atonement, which feasts begin with Rosh Hashanah (Lev 23:23-25).

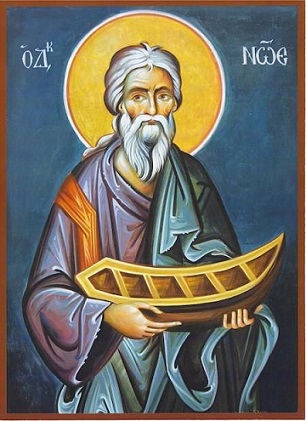

Tishri 1 as the beginning of the year took on additional significance through other events and personages associated with that day. Some of these associations are made in the Scriptures themselves, others arise in subsequent tradition. It was in the month of Tishri that the Ark of Noah came to rest on Mt. Ararat (Gen 8:4). Based on the giving of Noah’s age at various points in the narrative, it was concluded that Noah had been born on Tishri 1. This tradition served to connect the prophecy given at Noah’s birth (Gen 5:29) of rest and deliverance from the curse of Adam to the beginning of a new year. This further gave the story of Noah an eschatological character in the Second Temple period. The promise to Noah is that the cycle of years will continue until the time of the end of this age (Gen 8:21-22). The end of the age, then, was conceived of in parallel to the days of Noah before the flood came (cf. Matt 24:37; Luke 17:26; 1 Pet 3:20). Rosh Hashanah is known, beginning in Leviticus, as the Feast of Trumpets as the new year was begun with a series of trumpet blasts. Likewise, St. Paul sees the beginning of the age to come similarly marked (1 Cor 15:52; 1 Thess 4:16; cf. Matt 24:31).

Furthering this association was the association of Tishri 1 with the sixth day of creation, the day on which humanity was created. Tishri 1 is also the date on which David was crowned as king of Judah (2 Samuel/Kingdoms 2:11). Traditionally, from the time of Solomon, this became the date on which all subsequent kings of Judah were coronated. The new year, therefore, became associated with both the new creation and the beginning of the messianic age. In his Apocalypse, St. John depicts the coronation of Christ as king and his retaking of sovereignty over the earth in a series of overlapping cycles. In the first of these, the Lamb seated upon the throne opens the seals holding the claim to ownership of the creation (Rev 6). In the second cycle, the seven holy archangels who stand before the throne are given trumpets (8:2) to sound in sequence. The first six trumpets bring wrath and defeat upon Christ’s enemies. The sounding of the seventh trumpet will bring to completion the mystery of Christ as it had been announced through the prophets (10:7). Its sounding announced the enthronement of Christ and his eternal reign as Messianic king and God (11:15).

As in ancient Israelite and Second Temple practice, there is a second cycle within the calendar of the Orthodox Church which begins in September, on September 1st. This ecclesiastical new year is the beginning of a separate cycle of fixed feasts. These feasts include those surrounding the lives of the Theotokos and St. John the Forerunner, for example, which begin in September and end in August. September 1st, the feast of the indiction, has likewise been associated with particular figures and events. The Gospel reading for this feast, Luke 4:16-22, describes the beginning of Christ’s public ministry at the synagogue in Nazareth. In this reading, Christ reads the Greek text of Isaiah 61:1-2, which identifies the speaker as the ‘anointed’ one, the Messiah, and then proclaims that this Scripture has been fulfilled in their hearing. The new year is thereby associated with Jesus’ public self-identification as the Christ and as the beginning of ‘the year of the Lord’s favor’, the Messianic age.

The 1st of September is also the feast day of Joshua the son of Nun. This association of Jesus and his ministry with his ancient namesake is revelatory of the character of his life and ministry. Joshua is the figure who, after parting and crossing the Jordan, made war with the spiritual enemies of Yahweh the God of Israel as they were embodied in the giant clans who dominated the land of Canaan. This connection explains the prominent place that the exorcisms of unclean spirits, associated with these giants, played in Christ’s ministry. The routing of the giant clans was completed by David in his accession to the throne as anointed king. The celebration of the indiction, therefore, represents not only participation in Christ’s earthly ministry, the story of his defeat and humiliation of the evil powers who had enslaved humanity through sin and death (Col 2:15), but also in his enthronement over the creation at his ascension and the establishment of his kingdom. It anticipates the glorious appearing of Christ with the sound of the final trumpet and the coming of his kingdom in power.

The gospel itself, then, the identity of Jesus Christ, his mission, his victorious enthronement, and the great day of his second advent are built into the interwoven festal calendars of ancient Israel, the Second Temple period, and the Orthodox Church. Time is given structure not by mathematical constructs or earthly powers but by the Truth himself around whom it finds its purpose and meaning.