Popular conceptions of heaven and hell in the modern world have been deeply shaped by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Specifically, the conception of hell has been deeply shaped by the Inferno. which has enjoyed a far wider readership and fascination than the corresponding sections on purgatory and paradise. In fact, Dante’s particular vision of hell has had so profound an impact that debates over universalism in the present time tend to take for granted that anyone who accepts historic Christian teaching on eternal condemnation believes in some variation of Dante’s hell. Perhaps no other work of literature has so transformed Western Christianity’s popular understanding than Dante’s, with the possible exception of Milton’s. Both of these authors, however, were composing works of literature, not of dogmatic theology and their depictions ought not to be confused with the historic teaching of Christianity. The latter, of course, is foundational to the Orthodox Christian faith and not the former. To reveal Dante, or other similar depictions of hell to be fictional is not to overturn what the Church has historically taught regarding eschatology.

Popular conceptions of heaven and hell in the modern world have been deeply shaped by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Specifically, the conception of hell has been deeply shaped by the Inferno. which has enjoyed a far wider readership and fascination than the corresponding sections on purgatory and paradise. In fact, Dante’s particular vision of hell has had so profound an impact that debates over universalism in the present time tend to take for granted that anyone who accepts historic Christian teaching on eternal condemnation believes in some variation of Dante’s hell. Perhaps no other work of literature has so transformed Western Christianity’s popular understanding than Dante’s, with the possible exception of Milton’s. Both of these authors, however, were composing works of literature, not of dogmatic theology and their depictions ought not to be confused with the historic teaching of Christianity. The latter, of course, is foundational to the Orthodox Christian faith and not the former. To reveal Dante, or other similar depictions of hell to be fictional is not to overturn what the Church has historically taught regarding eschatology.

Dante’s literary efforts, however, stand in a line of inheritance which stretches all the way back to the Second Temple period in apocalyptic literature. Much of this literature, both within the Scriptures in the case of Daniel, Zechariah, and the Apocalypse of St. John or adjacent to them in the case of the Enochic literature, the Apocalypse of Abraham, and others, describes a journey through the invisible creation, the spiritual world. This includes, in many cases, journeys through the heavens and the underworld with reference to the eschatological fate of both spiritual and human beings. One does not have to accept that 1 Enoch is a historical narrative account of a vision received by the Enoch of Genesis in order to understand its value as a preserver of spiritual experience and knowledge from the Second Temple period. If one desires to understand the way in which the faithful of the Second Temple period understood the fate of human persons after their physical death, at the Day of the Lord, and afterward, there is a rich literature from which to draw for this understanding and there is coherent teaching to be derived. While nascent Rabbinic Judaism placed a ban on writing in the wake of the rise of Christianity, Christians continued to do so. There is, therefore, corresponding literature from the early Christian period which reveals how this understanding was maintained and transformed through the advent of Christ.

A critically important text in this regard is the Apocalypse of St. Peter. The composition of this text dates to around 135 AD and it forms a part of the Petrine literature of the early Church. On that date, it was not, of course, written by St. Peter himself. Rather, it along with the Gospel of Peter, elements of which texts seem to have cross-pollinated, enjoyed early popularity in the Egyptian church where they were taken to reflect the teaching of St. Peter as does St. Mark’s Gospel with the latter author being the founder of the Alexandrian church. So well regarded was the Apocalypse of St. Peter that there were those who considered it to be a book to be read in the churches, what we would today call canonical. Even those otherwise inclined, as Eusebius of Caesarea and Nicephorus, list it alongside 2 Peter as a text considered authoritative by some and not others. The Muratorian Canon states that the churches accept “only the Apocalypses of John and Peter but some do not want the latter read in the church.” While St. Clement of Alexandria quotes the Apocalypse of St. Peter as Scripture, St. Macarius the Great, in debating a pagan who was citing the text against him, rejects its authority as not deriving from St. Peter. Though ultimately not regarded as part of the New Testament by the Church, the Apocalypse continued to be cited authoritatively, in the way in which the early fathers were cited, into the fifth and sixth centuries AD. In this regard, it is not unlike its fellow early Christian apocalypse, the Shepherd of Hermas.

The text of the Apocalypse of St. Peter as an early second-century summation of preceding religious experience and the literature which recorded it. Its text is heavily dependant upon the apocalypse of 4 Ezra. One of the most important manuscripts of the text was found with 1 Enoch. The latter text is pre-Christian, the former pre-Christian with chapters added by a later Christian hand. The Apocalypse of St. Peter, however, is an entirely Christian document. In fact, in its second chapter, it seems to clearly allude to then-recent events in Palestine, the Bar-Kochva rebellion, in a way that clearly distinguishes Christian and unbelieving Jewish communities. The text’s chief aim is to portray the blessedness of the saints and the state of condemnation in Hades and it, therefore, presents this portrait in light of the death and resurrection of Christ, the defeat of death, the harrowing of Hades, and the transformation that this had wrought in the world following upon the earlier apocalyptic traditions and visions which portrayed the origin and fate of rebellious spirits and humans before the advent of Christ.

The Apocalypse of St. Peter reflects the two-stage eschatology which has been the teaching of Christianity since the beginning. This life is the arena of repentance. Material life in mortal flesh is the gift of God to human persons to allow for repentance and an escape from the fate of the demons. The text affirms that the purpose of the entire creation was humanity, specifically the destiny of humanity in Christ. Therefore unlike the angels who rebelled, the humans who joined in their rebellions were given life in this world ending in death as an opportunity. At the end of that mortal life, as was commonly held throughout the Second Temple period, the soul of the departed comes before the throne of God and thence to either paradise or Hades. There the souls experience a preliminary blessedness or condemnation until the end of this age. This first stage is not eternal. Christian teaching has never spoken of eternal heaven and an eternal hell to which souls depart as a permanent destination at death. This intermediate state is a part of this age.

The second stage begins at the end of this age, at Christ’s glorious appearing as he comes to judge the living and the dead. The Apocalypse of St. Peter describes the events which take place at this time, drawing upon the presentation of the Scriptures. Christ appears to judge with the saints and angels of the divine council who will share in his act of judging the living and the dead (Matt 16:27; 25:31; Mark 8:38; 2 Thess 1:7). The earth and Hades give up their dead who have their flesh restored in the general, bodily resurrection of every human person who has ever lived (Dan 12:2; John 5:28-29; Rom 2:6-16; 2 Thess 1:6-10). The Apocalypse of St. Peter also describes the gathering up of the various rebellious spirits for judgment, these being “the spirits of those sinful ones who perished in the flood, and of all those who dwell in all of the idols, in every metallic image, in every passion and in paintings, and of those that dwell on all the high places and in stone waymarkers whom men call gods” (Apoc 6).

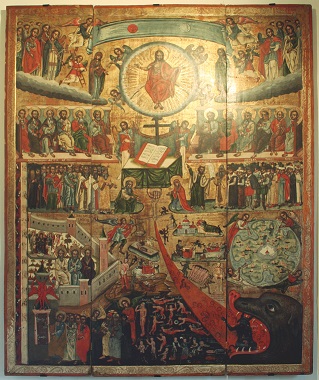

All of risen humanity and the demons themselves are immersed in the river of fire which purifies or torments them according to their deeds in the life of this age. This is explicitly the river of fire seen by Daniel in his vision and many subsequent fathers use the imagery of the river of fire coming from the throne of Christ at the judgment in precisely this way, following the interpretation which is taken by the Apocalypse of St. Peter. This river is depicted in Christian iconography of the last judgment. Those who have refused to repent in this life and to follow Christ come to share the fate of the rebellious spiritual powers in whose rebellion they have joined. This would have been the fate of all of humanity had it not been for the exile from the tree of life into this world and the dispensation of Christ. This judgment is not extrinsic and judicial but revelatory. All which is hidden is revealed and all are judged by the Truth (Matt 10:26; Mark 4:22; Luke 8:17).

The Apocalypse of St. Peter gives vivid, grotesque descriptions of the particular torments of those who have committed various grievous sins in the state of eternal condemnation. These will seem quite familiar to any reader also familiar with the works of Dante. Key to the presentation of the Apocalypse, however, is that those experiencing eternal condemnation are tormented by their sins themselves. The sins they have clung to and from which they refused to be set free now hold them captive permanently. It is for this reason that even they must admit that their fate is utterly just and deserved. At the same time that it makes these horrid descriptions, however, the Apocalypse of St. Peter is capable of moments of great beauty and tenderness. For example, it describes that the souls of infants aborted or exposed by their parents are carried to Paradise by angels who feed and care for them and raise them to adulthood in the kingdom.

After the last judgment, the fate of all angels and humans is fixed and eternal. Our oldest fragment of the Apocalypse of St. Peter, however, adds an important element connected to the practice of the Church from her very beginning. When St. Augustine addresses the Apocalypse of St. Peter in his City of God, he focuses on this element and its misinterpretation, though he ultimately misinterprets it himself (Civ. Dei 21.17-27). Specifically, the prayers of the saints, both in Paradise and on earth, grant mercy before the judgment seat of Christ for those in Hades. The souls of those who so find forgiveness actually receive baptism within a lake in Hades and thence depart purified. Within the Apocalypse, this is described in a way carefully worded in order not to suggest a universalism, but rather to reflect the Second Temple and later Christian practice of prayers for the departed. This practice is attested to in earlier literature but is here demonstrated to have been a part of Christian worship practice from at least the early part of the second century AD. This is both a part of the role of the saints in the last judgment (Matt 19:28; Luke 22:30; 1 Cor 6:3) and the power committed to the Church to bind and to loose in forgiving sins (Matt 18:15-20). This intercession is possible up to the last judgment. After this, both the righteous and the rebellious are confirmed in eternal life or condemnation. This second phase of Christian eschatology is eternal.

Both universalism and the teaching of purgatory misunderstand this data in a similar way. In the Second Temple period, apostolic Christianity, and the ante-Nicene Church the emphasis in the discussion of eschatology was nearly entirely upon the glorious appearance of Christ upon the earth to judge the living and the dead. Very little attention is devoted to the intermediate state of departed souls beyond the most basic affirmations as can be seen in both the Old and New Testaments of the Scriptures. The culmination of the gospel proclamation itself was that one must prepare one’s self to stand before the judgment seat of Christ at his parousia. Particularly in the Western church as time progressed the pendulum has swung to the other extreme. In most Christian contexts, very little attention is paid to Christ’s return to the point that Christians in these contexts frequently talk about the departed as being ‘gone’ to heaven or hell as if that were a permanent state. Certain sectarian groups, reacting against this general trend, move so far in the other direction that Christ’s imminent return becomes the sole topic of preaching and public witness.

Without the proper emphasis and understanding of the resurrection of the body and the life of the world to come, the transition between the two stages of Christian eschatology disappears. The transition then becomes an immaterial shift from one place or state to another. In many universalist frameworks, this is a shift for the temporarily condemned to share in the blessedness of the saints. In traditional Roman teaching, it becomes two stages experienced by the saved who proceed from a state of purgation to a state of blessedness while the condemned remain eternally condemned. Not only do these understandings distort Christian eschatology, but they are also at odds with the mission of the faithful to intercede for the departed, including the departed wicked. The prayers for the departed in the Divine Liturgy, in the memorial and funeral services, are not for the psychological assistance of the living faithful. They are offered as intercession for the salvation of those who have fallen asleep. The rituals associated with Soul Saturdays are no more ‘memorials’ in the bare sense than the Eucharist is. The Church ever intercedes, as a royal priesthood, for the life of the world and for its salvation, including the whole of humanity and the whole of creation.

After St. Peter and the apostles have received their eschatological vision in the Apocalypse of St. Peter, the text culminates in a particular event in the life of Christ. Not, as one might expect, in Christ’s crucifixion or resurrection. Nor does this vision come in the context of one of Christ’s post-resurrection appearances to his disciples and apostles and then culminate in his ascension. Rather, it culminates in Christ’s transfiguration atop the holy mountain. Christian eschatology has never focused on bodiless states of reward and punishment. Rather, it has always focused on the redemption and transfiguration of the entire creation in Christ, including our shared humanity. The Christian hope concerns not only or even primarily our individual souls, but our bodies and this world which will be delivered from corruption and permeated by the glory of God. And this Christian hope is not one to be held as we sit back in an armchair. We are not commanded to hope that all may be saved, much less to stomp our feet and demand it of God. We are commanded to work and to pray and in so doing to cooperate with Christ in bringing about the fulfillment of all of creation.

Hello Father Stephen. I am Roxana Kawas, from Guatemala. This is a dense subject, and I had a hard time understanding it because I don’t have a strong biblical background. I have never believed in the concept of purgatory as explained by the Roman Catholic Church. However as I read your post, a doubt came to mind. You mention that “…At the end of that mortal life, as was commonly held throughout the Second Temple period, the soul of the departed comes before the throne of God and thence to either paradise or Hades. There the souls experience a preliminary blessedness or condemnation until the end of this age.” And later on you mention that these are “temporary” stages, until the second coming of Christ, when he will come to judge the dead and alive. But, if people went to heaven or hades, why would there be a second judgement? Wouldn’t then make this “temporary heaven or hell” be then what the Romans describe as the timeframe for purgatory? Thank you for any clarification you can provide.

The intermediate state, the state after death and before the resurrection, is temporary because of the reality of Christ’s return and the bodily resurrection. So, Paradise is the word we use to describe the state of souls absent from the body and present with Christ. When the day of Christ’s appearing comes, they will not continue in that state forever. They will be raised from the dead bodily and live for eternity in the new heavens and the new earth. They will live a bodily existence in a transfigured creation. Likewise, Hades is what we call the state of the departed who are absent from the body but still mired in sin. This existence is likewise temporary as when Christ appears, they will also be raised from the dead and experience eternal condemnation. There is the added element, however, that some of those in Hades, maybe even some significant portion, will receive mercy before Christ’s judgment seat through the prayers of the faithful and the Church.

Purgatory as traditionally taught by Rome is a third place, in addition to Paradise and Hades. In order to enter Paradise, they teach that a soul must be perfect. Therefore any soul destined for Paradise must spend time in Purgatory, or pass through a state of purgation of varying lengths before it enters heaven. Everyone in Hades or Hell in their system is there eternally. Everyone in Purgatory will eventually get to Paradise or Heaven. Prayers offered for those in purgatory serve to shorten the amount of time that the soul spends in that state. So this is a very different concept. As I mentioned in the post, I hold the chief problem with it to be the way in which it ignores the return of Christ and the bodily resurrection. This is true to the degree that it is very difficult to find an answer with any official imprimatur to the question of what happens to souls in purgatory at the time of the bodily resurrection.

Thank you very much Father Stephen. This was very helpful and now I understand it much better. Kind regards, Roxana

Very helpful. Thank you, Father.

Nailing it as usual!

Dear Fr. Stephen,

Father, bless!

This article is superb and cuts right through the historical naiveté of accounts like DBH’s most recent work on universalism. I appreciate also that you did not (explicitly) enter that fray of controversy, but are simply producing this kind of careful scholarship, letting it speak for itself. Thank you for a solid eschatological apologia on behalf of the Orthodox faithful.

Do any of the Fathers speak to what becomes of our shared human nature after the final judgement? St. Silouan said “my brother is my life.” What will it mean for our brother (sister, father, mother, child) to be in hell?

This is why we never stop beseeching our brethren day and night with tears to be reconciled to God (Acts 20:31). It’s why we pray for them during this life and after. So that such a tragedy might not come to pass.

Indeed, thank you Father!

Fr. Stephen, have you read the article by Peter Chopelas titled _Heaven & Hell in the Afterlife According to the Bible_? You can find it online here:

https://preachersinstitute.com/2009/11/03/heaven-hell-in-the-afterlife-according-to-the-bible-peter-chopelas/

Mr. Chopelas seems to focus more on linguistic arguments related to misleading translations. Given your background, I’d be interested in any comments you have on the Chopelas article and how your views on the subject differ from his.

I don’t normally like to comment on particular people’s work or articles directly in this space. Due to the apparent influence that this piece has exercised, however, I will make a couple of brief comments.

First, neither the Scriptures nor the Orthodox Church teach that after death human souls exist eternally in a state of ‘heaven’ or ‘hell’. Any eschatology that isn’t firmly focused on Christ’s parousia, the bodily resurrection, and life in a transfigured creation is sub-Christian.

Second, this is not an article of linguistic arguments. It is primarily English word studies using dictionaries and concordances which is not to be confused with actual language work. It is also full of urban legends and folk etymologies that are demonstrably not true. At several points it presumes that teachings of later Rabbinic Judaism represent pre-Christian and therefore ‘inherited Christian’ beliefs which is false and anachronistic.

Finally, his central argument, that eternal condemnation is not a separation from God is based on half-truth. The imagery he wants to point to of sin being unable to stand in the presence of God’s holiness without being consumed by fire, is certainly in the Scriptures, though not in a lot of places that he here tries to find it. There is also, however, equally language of separation, being cut off, being locked out of the kingdom, etc. for which he isn’t accounting.