The Book of Jubilees is an ancient Jewish text from the Second Temple period. As a text, it played a significant role in the religion of the first century AD. Josephus made heavy use of it in his Antiquities. In addition to being a textual composition, Jubilees is a repository for a vast swathe of Jewish religious and historical traditions providing a window into the understanding and practices of Jewish people during this period. Many of the ideas found in Jubilees appear in the New Testament, casually mixed as traditions with the text of the Hebrew scriptures themselves. In a handful of places, the New Testament authors seem to cite Jubilees directly. Many of the earliest Fathers reference this text as well. Though it is less well-known than the related 1 Enoch, it is a text which is no less influential or important.

The Book of Jubilees is an ancient Jewish text from the Second Temple period. As a text, it played a significant role in the religion of the first century AD. Josephus made heavy use of it in his Antiquities. In addition to being a textual composition, Jubilees is a repository for a vast swathe of Jewish religious and historical traditions providing a window into the understanding and practices of Jewish people during this period. Many of the ideas found in Jubilees appear in the New Testament, casually mixed as traditions with the text of the Hebrew scriptures themselves. In a handful of places, the New Testament authors seem to cite Jubilees directly. Many of the earliest Fathers reference this text as well. Though it is less well-known than the related 1 Enoch, it is a text which is no less influential or important.

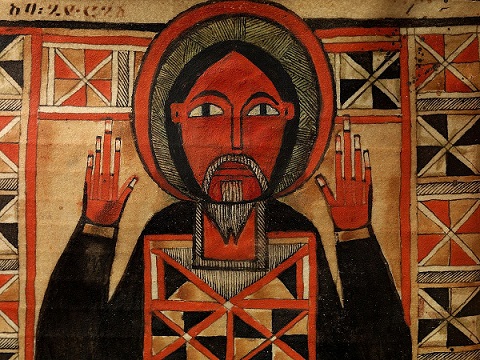

The Book of Jubilees was written in the middle part of the second century BC, very likely in Palestine. The earliest known manuscript portions are in Hebrew and Aramaic and were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. A major portion of the text also exists in Latin and a great deal of the Greek can be reconstructed from patristic citations. The entirety of the text of Jubilees is available from Ethiopian sources in Ge’ez recension. Its Ge’ez title is, “Book of Divisions.” The text is, in general, considered canonical by both Ethiopian Jews and Christians resulting in its preservation in various codices. The comparison of the text in these various languages allows for a high degree of certitude regarding the state of the text in the Second Temple period as the New Testament authors would have known it. There are many links in themes and content between Jubilees and the Enochic literature. It was so foundational to the community at Qumran which produced the Dead Sea Scrolls that it is the third most commonly found text, following Genesis and 1 Enoch.

At its core, Jubilees is an expansionistic re-telling of the narratives of Genesis and Exodus. In many sections, it operates under the same principle as many of the Aramaic targums, incorporating other traditional elements, even whole stories, into the maintained Biblical text. In other places, it greatly condenses and summarizes the material of Genesis and Exodus, seemingly in places of less interest to the author. In the places where the original text of Genesis and Exodus is maintained, even in the Hebrew fragments of Jubilees, the Hebrew text does not match either the traditional Hebrew text or the Hebrew text which underlies the Greek Old Testament tradition. This implies that the text which the author of Jubilees reworked was another, independent text or text tradition so far undiscovered. This point once again to the fact that in the Second Temple period and at the time of Christ, there was not a set text of the Hebrew Scriptures. Rather, the Hebrew Scriptures represented a wider textual tradition that included several forms of the texts which would later make up the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament.

Beyond this early witness to the text and understanding of Genesis and the early portion of Exodus in the Second Temple period, Jubilees makes several significant contributions to the understanding of Jewish religion in the period. It does this in two primary ways, through the traditional material incorporated into the text and through the arrangement of that text. Jubilees purports to report the vision received by Moses at Mt. Sinai when he received the Torah from the Angel of the Presence. The text is therefore based on the presupposition that Moses’ knowledge of the primordial history recorded in Genesis came to him through such a visionary experience in his prophetic role. This brings to bear apocalyptic themes in the text, though apocalyptic is a feature of the entire text of the Scriptures. The reason for the title of the book is its organization and structure.

As for the authors of the Enochic literature, the calendar was of key importance to the author of Jubilees. Jubilees retroactively describes the history of the world to the point of Moses in light of the structure given to time by the Torah itself. It, therefore, divides the primeval history according to weekly sabbaths, festal cycles, sabbath years, and jubilee years although strictly speaking these structures and feasts had not yet been instituted. This results in anachronisms such as the Feast of Tabernacles being celebrated by the patriarchs in Canaan centuries before the wilderness wanderings which inspired it. Jubilees, however, taking its cue from the structure of the creation of the world in Genesis 1 as a week ending in a sabbath, sees these structures of measurement as built into time itself. They have therefore existed since time was itself created, since the beginning of this age, whether or not humanity recognized their existence. This, in turn, suggests something about the nature of the Torah. If the moral, religious, and even temporal structures encoded in the Torah are embedded in the creation itself, this makes the Torah not legislation but revelation. This conception of the Torah is paralleled by St. Paul’s argument in Romans 1 and 2, in which the apostle states that the God of Israel is knowable from the creation itself, such that Gentiles who have been attentive to that creation can become a Torah for themselves (Rom 2:14).

Thematically, much of Jubilees focuses on the spiritual beings of the invisible creation, both ranks of angels and the origins of demons in general and disembodied demonic spirits in particular. Angels are assigned to every aspect of creation and as guardians of human persons and nations by God to administer his rule. The story of the origin of Mastema is narrated. Jubilees narrates the story of the Watchers in a manner parallel to that of the Enochic literature, as the angels who left their former estate, entered into sexual congress with human women and produced the race of giants destroyed by the flood in the days of Noah and by the descendants of Abraham subsequently. It goes further, however, in describing the means by which one-tenth of those spirits were allowed to remain upon the earth, explaining the unclean spirits of the Hebrew scriptures and demons as described by Tobit and the Synoptic Gospels. These themes are integrated with the calendar structure of the book as a whole through Jubilees’ understanding of the link between events in this world and those in the spiritual world. Events in this world, in this age, are the product of either participation by humans in the work of Yahweh, the God of Israel or in the rebellion of the evil spiritual powers. Because human persons bridge the invisible and visible creations by being constituted of body and soul, the events of these two worlds overlap. In the Book of Jubilees, the casting down of the Watchers into the abyss is accompanied by the defeat of the Rephaim and the Amorites by the armies of Israel. While this is true as a general principle of history for the author of Jubilees, it is nowhere more true than in the context of worship in its various cycles in which heavens and earth unite as one; the worship of humans with that of the angels.

The influence of Jubilees manifests itself in the New Testament in two ways. There are a number of instances in which traditions contained within the text of Jubilees are references by New Testament authors. In these cases, it would be difficult to demonstrate that Jubilees is a source for the New Testament document. Both texts may simply be drawing on a common tradition. But in these instances, the book of Jubilees represents the earliest known textual form of the tradition in question. St. Stephen’s speech in Acts 7, for example, repeatedly references traditions not contained in the traditional text of Genesis and Exodus but included in the book of Jubilees. He references the remains of not only Jacob but all of the patriarchs being brought back to the tomb at Shechem (Acts 7:15-16; Jub 46:9). He references the age of Moses at the time of his killing of the Egyptian as recorded in Jubilees (Acts 7:23; Jub 47:10-12). He likewise references the number of years which Moses spent in Midian (Acts 7:30; Jub 48:1). St. Stephen references the law as having been given by angels, a tradition recorded in an earlier form in Jubilees (Acts 7:53; Jub 1:27). Suffice it to say that St. Stephen narrates the early history of Israel in a way parallel to the book of Jubilees.

Second Peter likewise appears to reference traditions contained within the book of Jubilees. This is in addition to the clear allusions in 2 Peter to elements of the Enochic literature (eg. 2:4-10). Noah is referred to as a “preacher of righteousness” by St. Peter here, despite there being no account in Genesis 6-7 of Noah preaching to anyone (2 Pet 2:5). Jubilees not only describes Noah as a preacher to his corrupt generation but records one of his sermons (Jub 7:20-39). The description of the renewal of the heavens and the earth in 2 Peter 3:13 is paralleled by the language of Jubilees 1:29. This particular expression of the restoration of creation is not spelled out before Jubilees in sources currently possessed. St. Peter cites the maxim that to the Lord, “one day is as a thousand years” (2 Pet 3:8). Jubilees likewise records this expression (Jub 4:30).

There are several cases, however, in the New Testament which appear to be something closer to direct citations. Possibly the most important of these is a quotation from Christ himself in St. Luke’s Gospel. Christ quotes the Wisdom of God as saying, “I will send prophets and apostles to them and some of them they will kill and will persecute” (Luke 11:49). This appears, based on key vocabulary, to be an abbreviated quotation of Jubilees 1:12. In the context of Jubilees, this was spoken by the God who revealed himself to Moses regarding the fact that the Israelites would later go astray and murder his prophets. The murder of the prophets of God by Israel is precisely the context in which Christ makes this quotation in Luke (11:47-51). A second reference by Christ appears to take place in St. John’s Gospel. Christ promises his disciples and apostles that when the Holy Spirit comes, he will cause them to remember all the things which Jesus said and did which they had seen (John 14:26). In Jubilees, God in his encounter with Jacob at Bethel, following Jacob’s vision, tells him in the same words that he will cause him to remember all the things which he saw in the vision so that he will later understand them (Jub 32:25).

St. Paul, likewise, appears to reference the Book of Jubilees on a few occasions. In 2 Corinthians 6:15, at the end of a catena of Old Testament quotations about the people of God coming out and being separate and holy to the God of Israel, the apostle appends the quotation, “I will be a Father to you and you will be sons and daughters to me” (2 Cor 6:18). Many English Bibles footnote this text as being a reference to 2 Samuel 7:14, in which Yahweh tells David that he will be a father to Solomon and Solomon a son to him. In the context of St. Paul’s quotation, this makes little sense. The reference in 2 Samuel is to the tradition of the king of Israel as the son of God, anticipatory to the Messiah. St. Paul’s citation, on the other hand, is directed toward the entire people of Israel, explicitly toward men and women equally. He nowhere implies that this is with reference to them being made to be kings (and queens?) based on their holiness. The book of Jubilees, however, provides a direct parallel quotation in which the God of Israel tells Moses regarding the people of Israel that when they keep his commandments, he will be a father to them and they will be his children (Jub 1:24).

St. Paul makes other passing references to details found in the Book of Jubilees elsewhere in his epistles. In 2 Thess 2:3, he refers to the coming antichrist as the “son of perdition.” This is one of the titles given to the giants destroyed by the flood (Jub 10:3). In his Epistle to the Galatians, St. Paul uses the phrase “Gentile sinners” to refer to those outside of the Christian community (2:15). This same phrase is found in Jubilees in a similar context (Jub 23:23-24). A further detail cited by St. Paul in Galatians has caused considerable trouble to scholars devoted to a literal interpretation of Biblical numbers. St. Paul states that the Torah was given 430 years after the confirmation of the covenant with Abraham (Gal 3:17). This does not match the typically constructed timeline of the book of Genesis and Exodus utilized by scholars. It is also difficult to get that number to jibe with the dating given in Exodus 12:40 which states that Israel was in Egypt for 430 years. The Book of Jubilees, however, in line with its structure according to cycles and years records the period of time from the birth of Isaac to the giving of the Torah as precisely 430 years (Jub 15:4). Because the timeline of Jubilees is composed with such precision, this is likely a citation of the information from Jubilees rather than a shared tradition.

The Apocalypse of St. John contains at least two allusions to the Book of Jubilees. The phrase is used twice in the Apocalypse regarding the identity of the church that it has been made “a kingdom and priests,” rather than the more common “a kingdom of priests” or even “a royal priesthood” (Rev 1:6; 5:10). This wording is found, however, in the Book of Jubilees as a promise to God’s people Israel (Jub 16:18). Jubilees 2:2 speaks of particular angels giving voice at the time of the giving of the Torah. These angels are assigned to particular aspects of creation. These are the “angels of the voices and of the thunder and of the lightnings.” Repeatedly in the Apocalypse, as St. John stands in the heavens, at key moments, he hears, “lightnings and voices and thunderings” (Rev 4:5; 11:19; 16:18).

These are key and clear examples of the influence of Jubilees and the traditions which it contains upon the authors of the New Testament. Many more examples could be given. Likewise, countless examples of points of connection could be given to Orthodox worship and liturgy. As but one example, one of the prayers of the Trisagion for the Departed begins with the words, “O God of spirits and of all flesh…” This is the phrase that begins Noah’s prayer asking for the deliverance of his children and grandchildren from the power of demons in Jubilees 10:3. Suffice it to say that the Book of Jubilees, regardless of canonical status, is a critically important witness to the interpretation and religious significance of Genesis and Exodus in the first century AD. It is invaluable as background to the apostles and New Testament writers in understanding their religious worldview and experience. The texts which make up the Christian Scriptures are not timeless texts. They were produced by real men in real times and places, men, times, and places chosen by God for this purpose. They cannot be understood outside of this divinely chosen context.

Very interesting article; I didn’t know Jubilees existed!

Thankyou and God bless…..

“Events in this world, in this age, are the product of either participation by humans in the work of Yahweh, the God of Israel or in the rebellion of the evil spiritual powers. Because human persons bridge the invisible and visible creations by being constituted of body and soul, the events of these two worlds overlap.”

Could you elaborate on this point?

Thank you, Father Stephen, for presenting to us the importance of this particular extra-biblical text and for the examples you provide in the Old and NT. i can see how Jubilees’ focus on Genesis and Exodus shows us the importance of understanding the foundations of our faith, way back to our beginnings.

One thing (among many)I find very interesting is how in Jubilees a festal calendar is presented to us to form the connection between the physical and spiritual world. Very much an Orthodox concept.

Another thing occurred to me. We speak a lot about tradition, using a “T” or a “t” in order to distinguish between Tradition and tradition. I’m not sure I understand the difference, if there is any. By what you say here, there is tradition within “wider textual tradition”, and both are pertinent and equally important. Would it be correct to say there’s one tradition from the beginning, that was revealed to us, in time, through creation, that over the years has been spoken about in different ways? I think we sometimes run into problems in our attempt to delineate between Tradition and tradition, by placing one over the other in importance.

Question, Father….I have a book titled “The Books of Enoch, Jubilees, and Jasher” where the first two books are translated by R.H. Charles, published in 1917 (re: Jasher, the translator is unknown). What are your thoughts about his translation?

Those translations of 1 Enoch and Jubilees are the standard translations in English, though as you note, not totally up to date. The Book of Jasher was shown to be entirely a hoax. The ‘Book of Jasher’ is mentioned several times in the Deuteronomic History in the Old Testament. What was circulated publicly in the early 20th century as ‘The Book of Jasher’ later turned out to be fraudulent, however.

Thank you Father.

I wouldn’t have known about Jasher had you not mentioned that. Thanks.

Thanks for this post. I’ve seen a handful of references and citations pertaining to this work, but never pursued the work. Now, I’ve begun reading a downloaded copy (pdf format) of the George Schodde 1888 translation.

Fr. De Young,

I’m working on a presentation on the Millennium. I want to make the point that John is drawing on the language of Jubilees 48:15 in Revelation 20:2-3 and, possibly, 12:10. I thought it might be prudent to demonstrate some precedent for the influence of Jubilees on the NT overall. An online search led me to your article on “The Book of Jubilees.” I just want to THANK YOU SO MUCH for you research here and the many parallels you point out! I will probably just quote your article to make my point. Have you written elsewhere on this topic and/or do you know of any other scholarly works that address this topic?

Robert C Jr

Excellent review and very practical, concise summary of some of the NT parallels and why it is important to have 2nd Temple writings in our filter of thought. Regarding the “430 years” mentioned by Paul, I find solid evidence that the Israelites were only in Egypt for about 215 years, with half of that time (also ~215 years) actually being the “sojourn” in Canaan before moving to Egypt. The Masoretic has multiple changes in both genealogy / ages from Noah to Abram (dropping 650 years off of the total span) that are not dropped by the Septuagint, samaritan Pentateuch, Josephus and Acts. This also effects the generally accepted scholarly opinion on the “date of the exodus” — it is my opinion that at some point there was scribal error (or perhaps an effort to establish Melchizadek as actually being Shem {because in the corrupted age of genealogies there is 650 years dropped, allowing for Shem to in theory outlive his 8th generation of progeny and thus be alive at the time of Abraham}, and therefore used by Jews to this day to discredit the claim of Jesus to be high priest after the order of Melchizadek). Anyways, this is another rabbit hole but it all makes a lot of sense to me that the sojourn of ~215 years plus time in Egypt of ~215 years (of which probably only 75-100 years were of forced labor, prior to that they lived in prime goshen land and thrived).