The pivotal moment in the life of Moses as related in Exodus is his prophetic call at the bush which burned but was not consumed. Within this call narrative, an important and well known moment is the revelation to Moses of the name of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Despite how well known this moment is, there are a number of misnomers regarding the revelation of the name Yahweh, as well as precisely what this name means and indicates. This is true not only in terms of popular understanding but even major scholarly theories based on references to this name have recently lost most of their popularity if not been completely overturned. Archaeological finds have given further relevant evidence in recent years. Finally, there has been a general inability to separate later Rabbinic practice regarding the divine name from that of the Biblical period.

The pivotal moment in the life of Moses as related in Exodus is his prophetic call at the bush which burned but was not consumed. Within this call narrative, an important and well known moment is the revelation to Moses of the name of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Despite how well known this moment is, there are a number of misnomers regarding the revelation of the name Yahweh, as well as precisely what this name means and indicates. This is true not only in terms of popular understanding but even major scholarly theories based on references to this name have recently lost most of their popularity if not been completely overturned. Archaeological finds have given further relevant evidence in recent years. Finally, there has been a general inability to separate later Rabbinic practice regarding the divine name from that of the Biblical period.

Possibly the most critically important misunderstanding of Exodus 3:15 and the revelation of the name Yahweh to Moses is that this is the first time that this name was revealed to anyone. The text does not say this. In fact, the text implies precisely the opposite. At the point at which Moses asks for the name of the God whom he has encountered in the Angel of the Lord in the bush, he is not inquiring out of curiosity, but to use the name as evidence to bring the elders of the people of Israel to believe him concerning his call as a prophet. God has already identified himself clearly as the God of their fathers, of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. One of Moses’ many concerns about his mission to Egypt is that the elders of the people will not believe him based on his past history as a member of Pharaoh’s household and a murderer. It is in this circumstance that God gives to Moses the name to tell the elders, further explaining that giving this name will cause the elders of the people to believe him. This means that the elders of the tribes of Israel in Egypt already knew the name Yahweh and would recognize it. This name was being revealed to Moses.

It is also worth noting in this context that Moses encounters this name while sojourning with the Midianites, the tribes of whom were descended from Ishmael and Esau. Moses father-in-law is a priest and not a pagan one as presented in the text. This means that he is himself already worshipping Yahweh, potentially even under that name. The earliest known records of the name ‘Yahweh’ as applied to a God comes from a pair of Egyptian inscriptions from the end of the 15th century BC listing a group of prisoners taken in battle. These prisoners, depicted as Semitic people and identified with the region of southern Canaan populated by the Edomites and Midianites, are identified ethnically as being from the ‘Shasu of Yahweh.’ Given the format of this identification, Yahweh would be the God whom they worship. Further, the mountain of God at which Moses has this encounter is presented as having been a known site for the nomadic peoples before Moses’ experience there. Later poetic and prophetic depictions in the Hebrew scriptures will present Yahweh as having come into Canaan from the region of Edom (eg. Deut 33:1-2; Jdgs 5:4-5; Hab 3:3-7). All of this would seem to reflect that the sons of Abraham other than Jacob/Israel and their descendants who had not gone to sojourn in Egypt had maintained patriarchal worship forms.

Offered against this understanding is chiefly Exodus 6:2-3, which states that while the same God was worshipped by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, “but according to my name Yahweh I was not known to them.” A woodenly literal interpretation of this verse became the basis for the documentary hypothesis in studies of the Pentateuch which at its base sought to separate the narrative portions of the Torah in particular into J (Yahwist) and E (Elohist) material. This literalist reading, however, isn’t born out by the way in which ‘knowing the name Yahweh’ is used elsewhere in Exodus and throughout the scriptures. First Samuel/Kingdoms 3:7 states that the young Samuel, “did not yet know Yahweh nor had the Word of Yahweh revealed himself to him.” This despite the fact that the text has already stated that Samuel is serving (in worship) before Yahweh and increasing in favor with him (2:18, 26). It is clear that we are not being told that Samuel did not know the name ‘Yahweh’. Rather, Samuel would later come to know Yahweh in a different and unique way than he had been known to him previously. Repeatedly in the book of Exodus, God himself states that the people of Israel will know him as Yahweh after certain events such as the deliverance from Egypt, Mount Sinai, and the conquest of the land (Eg. Ex 6:7; 16:11-12). Coming to know the God of Israel as Yahweh in this context, then, refers not to learning the name, but rather relates to having an experience of God related to the meaning of that name.

There are actually, technically, two different versions of the divine name given in Exodus 3:14-15. God’s first response to Moses is “I am who I am.” In Hebrew, this is ‘Ehyeh asher Ehyeh.’ Moses is told to tell the sons of Israel that ‘Ehyeh’ has sent him. Despite the parity here between the two forms of the name, for the remainder of the Hebrew scriptures, the name ‘Yahweh’ will come to vastly predominate (possible exceptions include 2 Sam 7:6; Ps 50:21; Hos 1:9). He is then immediately told in nearly exactly the same verbiage that he is to tell the elders of Israel that ‘Yahweh’ has sent him. Both of these names are forms of the Hebrew verb ‘to be’, ‘hayah‘. The form ‘Ehyeh‘ is the first person, hence the translation ‘I am’. ‘Yahweh’, on the other hand, is in the third person and would be more accurately ‘He is’.

Occasionally, interpreters will make an issue of tense. It should be noted, however, that Biblical Hebrew does not have a tense system as such. There are two verbal forms which indicate an action which is complete or an action which is open-ended. The former is generally translated as past or present tense in English. The latter, which is the form used in both forms of the divine name, is translated generally as present or future. It is, therefore, possible to translate these names as ‘I will be’ or ‘He will be’. Particularly in the first-person form, the same form is used in Exodus 3:12, a few verses earlier, when God tells Moses that he will be with him. A far simpler explanation of the verb form is that God’s existence and whatever else the name predicates of him is ongoing and unchanging.

The name ‘Yahweh’ is in the third person and according to its form, what is called in Biblical Hebrew the Hiphil binyan, has a causative significance. A literal translation would then be ‘He who causes to be’. The most obvious significance of this reading is that it makes Yahweh’s role as creator central to his identity in worship. Creation as such is not the sole emphasis, however. St. Paul identifies God as the one who “calls into existence those things which do not exist” (Rom 4″:17). This includes not only the days of creation but the nation of Israel (Is 43:1). This includes not only initial creation, but according to St. Paul and Isaiah is linked directly to the resurrection, reclaiming, and return. As the prayers of the Divine Liturgy say, “Thou it was who didst bring us from nothingness into being and when we had fallen away did not cease to do all things until thou hadst raised us up to heaven and endowed us with thy kingdom which is to come.” Does this prayer refer to the creation and the expulsion of Adam from paradise? Does it refer to Abraham’s seed and slavery in Egypt? Does it refer to the creation of Israel and their exile? The answer is yes. It is then in this sense that Israel, through the experience of the exodus and the conquest of the land, comes to know their God as Yahweh, the one who brings things into being.

One factor which leads to the misunderstanding of the meaning of the divine name is that it is not adequately translated into English. In fact, it is rarely translated at all. Scribal practice already by the Second Temple period, grounded in concern for the third commandment, had preserved the name Yahweh within the Hebrew text of the scriptures, but had moved away from pronouncing it in public reading, replacing it with a reference to simply ‘the name.’ In translations, including Greek translations of the Hebrew scriptures, the name was, in the lion’s share of cases, replaced with the word ‘lord’. This practice has continued to be followed by most English translations which translate, even when working from Hebrew texts, the name Yahweh in the Old Testament with ‘Lord’, often in all caps. This creates a certain ambiguity in New Testament usage of the term ‘kyrios’. In Greek, this word can simply be used to mean ‘sir’. It can also, however, be used to refer to Yahweh, the God of Israel. This ambiguity makes the repeated testimony of the New Testament authors that Jesus is Lord ambiguous enough for modern scholars to avoid recognizing this as an assertion of Christ’s deity.

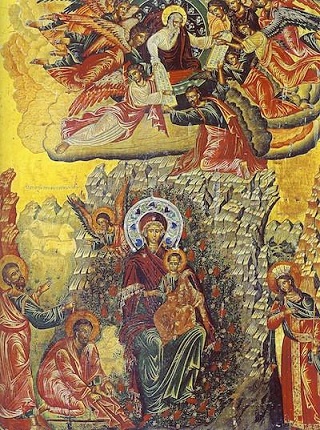

There are, however, places where Greek connections are more clear. The Greek translation tradition of the Hebrew scriptures rendered Exodus 3:14’s self-identification as ‘ego eimi o on‘. A very literal rendering of this phrase in English would be ‘I am He who is’. Each half of this statement in Greek was used, as was the first person form of the Hebrew name, in a minority of cases in the remainder of the Greek Old Testament and related traditions including the works of Philo of Alexandria and the Apocalypse of St. John (1:4, 8; 4:8). The participle ‘o on‘, ‘He who is’ or ‘the existing one’, is the form in which the divine name is likely most well known to Orthodox Christians. These three Greek letters appear within the cruciform nimbus of Christ in Orthodox iconography to identify him as Yahweh. It is also used verbally in the longer dismissal of daily services. The phrase, “Christ our God, the existing one….” or “He who is, Christ our true God…” is translating the phrase ‘o on‘, and could therefore more literally be rendered, “Christ our God, Yahweh, is blessed always, now and ever and unto ages of ages.”

The first portion of this phrase, ‘ego eimi’ or ‘I am’, is also of significance as it is used in regard to the person of Jesus Christ. In significant portions of the Greek Old Testament tradition, this Greek phrased is used to indicate the name Yahweh, particularly concentrated in the prophecy of Isaiah (eg. Deut 32:39; Is 41:4; 43:10; 46:4; 48:12; 51:12; 52:6). At several crucial points in St. John’s Gospel, this phrasing is directly attributed to the person of Jesus Christ. Obviously, connecting the use of the phrase ‘I am’, which most of us use countless times a day, to an explicit claim of deity must be justified. In the first place, Biblical Greek does not require a subject for the verb ‘to be’. Nor, in fact, does it require the verb if the subject is present. This means that the phrasing, “I [am] a man” or “[I] am a man” would read in the same way in Greek and be more efficient. They are, in fact, more common. Secondly, even if all of the cases in which St. John uses the phrase with an object, i.e. “I am [something]” are excluded to allow only the cases in which ‘I am’ occurs with no following identifier, there are still several attributed to Christ (John 8:24, 28, 58; 13:19; 18:5, 6, 8). Many of these instances are treated as blasphemy by the hearers, making the intent further clear. This identification is not only to proclaim Christ’s divine identity, but also to make clear that the name taught by Christ is another name for the same God worshipped throughout the ages.

In ancient times, God’s people came to know him as God Most High presiding over the divine council, as God All-Power and Almighty. Through the Exodus and the creation of Israel, they came to know him as Yahweh who brings into being that which was not. Through the incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ, they have come to know him by another name, “the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit” (Matt 28:19). It is not a coincidence that after revealing this new name to his disciples and apostles, just as he had revealed ‘Yahweh’ to Moses, Christ gives the promise “I am with you always” just as he had promised to Moses in Exodus 3:12 as he returned to Egypt to deliver the people. So he sends out the apostles to preach and baptize. Just as Israel worshipped by invoking the name Yahweh, so now the church calls upon the Trinitarian name of the Lord.

Hi Fr Stephen,

Here you have discussed how Moses would have understood the name Yahweh and how the Hebrews treated it down through history and in the scriptures to the point of our New Testament understanding of the trinity. Can you do the same thing with how the ancient Jews who were taught that God is One, which we now understand to be one divine essence and three persons, understood their experience with God and their ancestors experience with God when it comes to “the Word of the Lord” or the “Spirit of the Lord”. We know thanks to Christ about the Father Son and Holy Spirit. And thanks to St. John that the “Word became flesh” and we know at Pentecost the Spirit of God is poured out for all people dwelling within us. But what did the Jews make of those terms for God, did they recognize a distinction of person between Spirit and Word? What did second temple scribes make of Moses talking with God face to face yet at the same not able to see him? Did they recognize a distinction of essence and energy like we do now? Also, if you decide to tackle this one, can you explain how it was and how it changed, if at all, over time, for example from Abraham to Moses, first temple to second temple…that sort of thing. Thanks for your good work!

I actually did a series on that back in the long ago time. Links below.

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/05/16/the-angel-of-the-lord/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/05/23/god-the-word/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/05/30/the-son-of-man/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/06/06/gods-body/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/06/13/the-spirit-of-god-in-the-old-testament/

Exodus and Moses is one of my most favorite stories which can still apply to us today. The many times the people fell back into their old ways and behaviors even though there were many miracles, the Ten Commandments, and God’s hand in bringing them to safety in the parting of the Red Sea. (They were surrounded by a lot of evil, persecution, discrimination and leaders who wanted to drive them out)

This is how we still are today – falling back time and time again, forgetting the good God has done for us, the little miracles taking place each day and more! We only need to be focused in prayer keeping God-centered while living with the evils around us.

Thankyou and God bless!