This week serves as a sort of epilogue to the recent series on Christ in the Old Testament. These previous posts discussed the reality that Second Temple Judaism, through a close reading of the Hebrew scriptures, had developed the idea that there is a second hypostasis of Yahweh, the God of Israel. The terminology for this within the Jewish world was to speak of the ‘Two Powers in Heaven’. The identity and origin of this second hypostasis was the subject of much debate and conjecture in Jewish literature. The New Testament authors clearly identify the second person of the Godhead as Jesus Christ, incarnate in their day. In response to this core argument of the Christian proclamation, the Jewish community which rejected Jesus as the Messiah repudiated the idea of ‘Two Powers in Heaven’ entirely in the second century.

This week serves as a sort of epilogue to the recent series on Christ in the Old Testament. These previous posts discussed the reality that Second Temple Judaism, through a close reading of the Hebrew scriptures, had developed the idea that there is a second hypostasis of Yahweh, the God of Israel. The terminology for this within the Jewish world was to speak of the ‘Two Powers in Heaven’. The identity and origin of this second hypostasis was the subject of much debate and conjecture in Jewish literature. The New Testament authors clearly identify the second person of the Godhead as Jesus Christ, incarnate in their day. In response to this core argument of the Christian proclamation, the Jewish community which rejected Jesus as the Messiah repudiated the idea of ‘Two Powers in Heaven’ entirely in the second century.

While the Spirit of God or the Holy Spirit appears in the Hebrew scriptures, there was far less conjecture about his identity and origin. This is likely for several reasons. His identification as the Spirit of God adequately describes his relationship to Yahweh. Yahweh and his Spirit can clearly be distinguished from one another, but it is at the same time clear that his Spirit is not someone other than the God of Israel. His Spirit is not, on the one hand, a second God, nor on the other hand, some kind of inferior created being, because it is his Spirit. Likewise, it makes no sense to consider the origin of God’s Spirit. Someone’s Spirit exists for just as long as they do, and so in the case of the Holy Spirit, this is clearly forever. Less is said concerning the Holy Spirit in Second Temple Jewish literature because his existence is quite clear, and less discussion and conjecture was required.

The Holy Spirit was seen and experienced in the Old Testament in two primary ways. The first is directly, as the Spirit, Presence, and Power of Yahweh, the God of Israel. And so we see him at the very opening of the book of Genesis, ‘hovering’ over the waters (Gen 1:2). The word here is actually a word used for a bird brooding over her eggs. This imagery is intended to convey that the Spirit is the one who brings about and nurtures life. Psalm 33:6 says, “By the Word of the Lord the heavens were made, by the Spirit from his mouth all their hosts.” The New Testament, and later Nicene characterization of the Creation of the cosmos as a Trinitarian act is therefore seen to be based in a reading of the Old Testament scriptures. And this is not the only place in which we seen Trinitarian action within the Pentateuch.

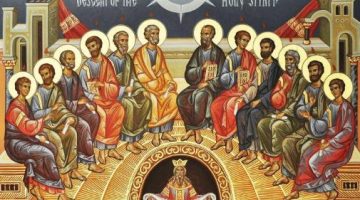

As Israel was led out of Egypt, they were guided by the Presence of the Lord, who went before them. This Presence is described as a pillar of cloud by day, and a fire by night (Ex 13:21). At different points, the God of Israel says that Israel was led out of Egypt by he himself (Ex 20:2, Lev 11:45, Deut 5:6), by his Angel (Jdg 2:1), and by his Presence (Deut 4:37). This fiery or shining cloud will be the descriptor of the Presence of the Lord throughout the Old Testament. This presence descends upon the tent of meeting when the God of Israel is there to speak with Moses (Ex 33:7). At the beginning of the worship of the Tabernacle, we see fire come out from the Presence and consume Israel’s offering (Lev 9:24), and then soon after to consume Aaron’s erring sons (Lev 10:2). This same Presence comes and fills Solomon’s Temple after its dedication (1 Kgs 8:10), and when the Lord again appears to Solomon as he had in his childhood, he identifies the temple as the place where he has placed his Name (1 Kgs 9:3). This identifies the shining cloud as the God of Israel himself. While it is very clear that Yahweh, the God of Israel, is not confined to this building in Jerusalem, he clearly states that he is fully present there in a unique way, in his Presence proper. This is, in essence, the definition of a hypostasis. It is worth noting that the cloud of God’s Presence does not return to the temple at its re-consecration under Ezra (Ezra 6:16-18), nor the re-consecration in the Maccabean period (2 Macc 10:5-8). When next we see this fire of God’s Presence, it is in the Holy Spirit’s descent to indwell the disciples of Christ on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:3-4). This makes every Christian believer a temple of the living God (1 Cor 6:19).

The day of Pentecost ties together the cloud of God’s Presence with the other way in which the Holy Spirit operates within the Hebrew scriptures, and this is in the indwelling of certain individuals. We see this first and foremost in the person of Moses as the preeminent prophet. In the book of Numbers, the Spirit is shared from Moses to the elders of Israel, causing them to prophesy (Num 11:16-30). Joel 2 prophesies that in the last days, the Spirit will be poured out on all flesh, and all will prophesy, as fulfilled on the day of Pentecost. This is the primary function of the indwelling of the Spirit in the Old Testament, that the words of the indwelt prophet becoming the words of God himself. St. Peter sees this as programmatic, stating in 2 Pet 1:21 that, “No prophecy ever came by the will of man, but prophets, though human, spoke from God as they were carried by the Holy Spirit.” The indwelling of the Spirit was not, however, limited to prophets, but was extended to kings and other leaders such as Saul (1 Sam 10:10) and David (1 Sam 16:13) who received the Spirit with the anointing with oil which designated them as king. In their lives, we see the Holy Spirit empower not only words from God, but divine actions (cf. Jdg 6:34). It is worth noting that the Holy Spirit would also depart from these leaders if they fell into unrepentant sin. This happened to Saul (1 Sam 16:14), and David feared it happening in his own case after his sin (Ps 51:11). In all of these cases, the indwelling of the Holy Spirit had the character of imparting leadership by making the indwelt human person an agent, a participant, of divine action in the world. For the words and the works which stem from his indwelling to be those of God, the Spirit must himself be the God of Israel.

Thus, when the New Testament authors speak of the Holy Spirit as God, they are following the Hebrew scriptures which they inherited. They are not innovating by speaking of a third divine hypostasis any more than they were in identifying Jesus Christ as the second hypostasis of Yahweh, the God of Israel. When, for example, the Holy Trinity is manifest at the baptism of Christ (Matt 3:13-17, Mark 1:9-11, Lk 3:21-22), this is not a shocking new revelation to a group of unitarian monotheists, but rather a clarification and identification of the persons of the Godhead already known within Second Temple Judaism. The New Testament writers, in speaking of the agent of the resurrection of Christ, speak of him being raised by the Father (Acts 2:24, Rom 8:11, 2 Cor 4:14), Christ rising himself (Jn 2:19, 10:18), and the Spirit raising Christ from the dead (Rom 1:4, 1 Pet 3:18). In doing so, they are not confused or disagreeing, but are following the pattern established in the scriptures by the accounts of the creation of the world, and of the exodus from Egypt. The resurrection of Christ is therefore the great Trinitarian action, the fulfillment of both the Triune God’s redemption of his people at the Pascha, and the beginning of the new creation.

Thank you Fr. Stephen for this entire series. It has been a great help in understanding the formation of our Faith. I am looking forward to future posts.

Wonderful as always! Thank you.