First John 2:2 states that Christ has offered himself as an atoning sacrifice “not only for our sins but also for the whole world.” For most of Christian history, this verse has been used as a football in various theological disputes. First, it was used as a proof text against the Donatists who saw their churches in North Africa as the totality of the church of Christ. Second, it was debated in regard to the condemnation of apokatastasis or universalism. Beginning in the period of the Protestant Reformation, it became a key text in the debate surrounding the Calvinist doctrine of limited or particular atonement. While what St. John has to say to the Johannine community in 1 John may apply in various ways to these later debates, it is quite clear that none of these applications reflect the original context. St. John was not writing against hypothetical first century Donatists or Calvinists. Nor was he writing in support of some universalist notion. Rather, St. John is applying a consistent understanding of atonement centered around the Day of Atonement ritual itself to the sacrificial self-offering of Jesus Christ.

First John 2:2 states that Christ has offered himself as an atoning sacrifice “not only for our sins but also for the whole world.” For most of Christian history, this verse has been used as a football in various theological disputes. First, it was used as a proof text against the Donatists who saw their churches in North Africa as the totality of the church of Christ. Second, it was debated in regard to the condemnation of apokatastasis or universalism. Beginning in the period of the Protestant Reformation, it became a key text in the debate surrounding the Calvinist doctrine of limited or particular atonement. While what St. John has to say to the Johannine community in 1 John may apply in various ways to these later debates, it is quite clear that none of these applications reflect the original context. St. John was not writing against hypothetical first century Donatists or Calvinists. Nor was he writing in support of some universalist notion. Rather, St. John is applying a consistent understanding of atonement centered around the Day of Atonement ritual itself to the sacrificial self-offering of Jesus Christ.

Paradise is the place where God dwells. After the creation of humanity, they were brought into Paradise to dwell with God and with the already created spiritual beings. Humanity was meant to grow to maturity and then depart from Paradise bringing Paradise, the presence of God himself, with him in order to transform the whole creation into Eden. Instead, by partaking of the knowledge of good and evil, humanity became subject to corruption and ultimately death. The first humans were expelled from Paradise, not because of their sin and uncleanness alone, but because for them to live eternally in that state would have made them like the demons, unable to repent (Gen 3:22-24). Rather than bringing Paradise with them, they brought their corruption with them and lived in difficulty within this present world.

The first transgression, in the garden, took place at the instigation of the devil. This pattern, of wicked spiritual powers influencing humanity to perform evil deeds, continued and intensified. This begins with Cain, the archetypal wicked man (Gen 4:6-7). In Second Temple Jewish thought, Cain is the archetypal sinner and wicked man. While his father was told that the ground was cursed because of him, Cain himself was cursed ‘from the ground’ (v. 11). While Adam would bring forth food from the earth by the sweat of his brow (3:17-19), the ground would not at all yield its fruit to Cain (4:12). Unable to live by the work of his hands, Cain founds a city so that he and his lineage create commerce, culture, and warfare.

What was true of Cain plays out in his genealogy (Gen 4:17-24). The corruption of the world continues and culminates in the figure of Lamech whose song to his two wives is emblematic of his sexual immorality and violent murder exceeding his forefather Cain exponentially by his own boast. This moral corruption was paralleled by spiritual corruption (Gen 6:1-7). In the interpretations found within Second Temple Jewish texts, this relationship, as with Adam and Cain, is causal. Rebellious spiritual powers are at work in and through human rebellion to corrupt and destroy the created order. It is the purification from the world of this evil and corruption which necessitates the flood as prophesied at Noah’s birth (Gen 5:28-29). St. John directly references these traditions surrounding Cain and his lineage in regards to the corruption of the world in 1 John 3:12-13. For St. John, the whole world lies under the power of the evil one (5:19) through this corruption. But Christ came to destroy the works of the devil brought about in the world by human persons (3:8).

The name attached to the leader of the supernatural powers involved in this corruption in league with Cain and his descendants in Second Temple literature is typically Azazel. So, for example, 1 Enoch 10:8 says, “The whole earth has been corrupted through the works taught by Azazel, ascribe to him all sin.” The use of this name serves to connect these traditions about the corruption of the world to the Day of Atonement ritual itself. The first of the two goats utilized in the Day of Atonement ritual is the goat ‘for Azazel.’ It is entirely possible that this was, at the earliest stage of the text of Leviticus 16, not a proper name but simply referred to ‘the goat who takes away.’ This is the goat into which the sins of the people were ritually placed by the high priest and which was then sent into the wilderness to die. In later, Second Temple traditions, this was understood to mean that the goat was taking the sins of the people back to whence they came, to the evil spiritual powers who had inspired them.

The Day of Atonement ritual took place annually and took place in addition to the regular cycle of sin and guilt offerings. This means that it served an additional ritual function above and beyond what those sacrifices accomplished. The Day of Atonement ritual, indeed all of the commandments of the Torah, are aimed toward preserving the holiness, purity, and cleanness of the Israelite camp and the later nation. Sin was seen to leave a metaphysical taint, a stain of impurity, on those who committed it and on the world around them. It brings spiritual corruption in the world. For God to continue to dwell within the tabernacle at the center of the camp and later the temple in the midst of the nation, not only must sin be atoned for through sacrifice, but this stain and corruption must be purified.

This is enacted within the Day of Atonement ritual. The sins of the people are placed upon the goat and sent away and the blood of the second goat is used to cleanse the sanctuary, the place where Yahweh himself dwells because this is the place in which that corruption and taint are the most dangerous. When the Torah was kept, it preserved first the camp in the wilderness and then the nation of Judah as holy and pure islands in the midst of a world which had been subjected to evil spiritual powers through sin and death. Those of the nations, ruled over by demons whom they worshiped, were unclean. Animals from outside the camp were unclean. Even physical objects were unclean and had to be cleansed and dedicated before they could be used in the sanctuary and then annually cleansed at the Day of Atonement.

The same literature which connects the corruption of the world in the earlier chapters of Genesis to Azazel and the cleansing ritual of the Day of Atonement also envisions an ultimate fulfillment to that ritual. Texts such as the Apocalypse of Abraham, which has been preserved for us in Slavonic by the Orthodox Church, describe an ultimate eschatological Day of Atonement at the end, connected with the coming of the Messiah, in which not only the sins of the people will be cleansed, but the entire world will be set free from the corruption of sin and death. This is fulfillment in the original sense, that the pattern of the old covenant is filled to overflowing by what is accomplished in the new. This event will represent a fulfillment of the entire Torah in that what the Torah merely managed and controlled on a small scale, this latter Messianic fulfillment will deal with once and for all.

That Christ’s atoning, sacrificial death represents this fulfillment is ubiquitous among the New Testament authors. The Synoptic Gospels, and St. Matthew’s Gospel, in particular, present Christ as fulfilling the role of both goats through his suffering and death. St. Luke in his two-volume work, his Gospel and Acts of the Apostles follows the same trajectory at the pivot point from one volume to the next. The end of St. Luke’s Gospel culminates in Christ’s self-revelation on the road to Emmaus followed by the continued praise and worship offered by the original Christian community in the temple. This parallels the events of the Maccabean revolt in which the climactic battle at Emmaus was followed by the rededication of the temple after it had been desecrated and abandoned under Antiochus Epiphanes. This Lukan rededication of the people as a temple is followed at the beginning of the Acts of the Apostles by the coming of the Holy Spirit, the presence of Yahweh himself, to fill not a new building, but his people. The sacrifice of Christ had not only purified and cleansed them to allow the Spirit to dwell within them but had also expanded the boundaries of the camp to encompass the entire world, such that Gentiles and even wild animals were no longer unclean (Acts 10:9-23).

Though this final purification of the world is accomplished in principle in Christ’s death and resurrection, it finds its application in the world of time and space over the course of the period preceding Christ’s return. That all food is clean finds its expression in the lives of the faithful when that food is received with prayer and thanksgiving (1 Tim 4:4). For St. John, Christ came to destroy the works of the evil one (1 John 3:8). This finds its fruition within the community of the church. “We know that we are from God and the whole world lies in the power of the evil one” (5:19). Just as those who are, like Cain, from the Devil bring sin and corruption and death into the world, so also those who are from God bear fruit of purification and life. Just as they actualize the works of the evil one in time and space, so also the one in whom the Spirit dwells brings the works of God into the world of time and space. God calls these works good because they are his works.

St. Paul tends to speak of this in Adamic terms. The body of the Christian, as the result of Christ’s atoning death, is a temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19-20). This means that, as was the intent with the first created man, the Christian as the presence of God within him as he goes out into the world. The Orthodox Divine Liturgy culminates not in the reception of the Eucharist, but in the dismissal when the faithful, having received Christ into their bodies, are sent out into the world bearing him with them. The entire creation is now the possession of our Lord Jesus Christ who wields all authority within it. We, as his assembly the Church, bring that rule and its effects to realization within the world as we receive God’s creation, bless it and hallow it. This includes the baptismal reception of the people of the world but extends also to every level of the created order, animate and inanimate. This is the work of the church in the world until the last day when there will be no temple because the whole creation will be the dwelling place of the Lord God Almighty and of the Lamb (Rev 21:22).

Dear father

At the beginning of your excellent post you write: Humanity was meant to grow to maturity and then depart from Paradise bringing Paradise, the presence of God himself, with him in order to transform the whole creation into Eden.

How do we know that this was our original purpose? Are you speaking fromt the bible itself or perhaps some other source?

In Christ

It’s from the scriptures themselves. I’m working from two major themes, the creation mandate given to humanity as an extension of the work of creation and the way in which Eden is described as a temple. In addition to the posts linked in this article, I talk more about those themes in the posts below.

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/06/19/man-as-the-image-of-god-in-reverse/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2019/06/24/being-and-chaos/

Thank you, that helped my understanding. I asked, because I cannot find a clear “mission-statement”, if you will, but clearly such a statement presents itself indirectly.

Hello Father.

Thank you for this helpful post.

I’m writing to ask if N.T. Wright has been a shaping influence in your theological formation. Some of the pieces you’ve written remind me of Wright, in that they assume the entire canon and the history surrounding it. I especially appreciate your emphasis upon Biblical Theology.

Thank you again, and God bless you.

Doug Sangster

I’m not totally conversant with all of Wright’s literary output. No human could be. But Wright was very much the pioneer of the approach that the New Testament and Christian origins ought to be understood in the context of Second Temple Judaism and the Greco-Roman world, as obvious as that might now seem. And that is very much my approach, though in some of my conclusions I end up disagreeing with Wright.

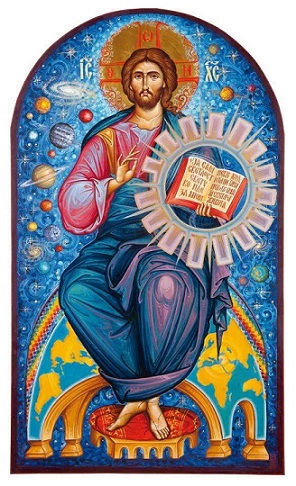

Thank you for another great post, we’ve been attending an Orthodox Church since January and you’ve posts have been very helpful, along with your podcast. I really like the icon, where can I find it?

Thank you for this helpful post Father!

You mentioned that the Apocalypse of Abraham had been “preserved for us in Slavonic by the Orthodox Church.” But isn’t it the case that it was preserved, not by the Orthodox Church, but by the Gnostic sect of the Bogomils?

Not actually. The Bogomils only existed for a sliver of time in the middle ages. Someone translated the text from Hebrew to Greek and preserved it until the 10th century. Someone continued to preserve the text in Slavonic from the 13th to 16th centuries. Both of those, minimally, took place within the Orthodox Church. One can argue that it was the Bogomils who undertook the Slavonic translation, but there is no actual evidence of that. The evidence just points to the fact that certain Second Temple Jewish texts in Slavonic recension were popular with the Bogomils. The fact that a text was popular with a group doesn’t taint the text, though it has been viewed that way historically. Exhibit A would be St. John’s Apocalypse which took centuries to really be resolved to be canonical largely because of its use by the Montanists.

There’s also the ‘chicken and the egg’ argument with certain texts within the Apocalypse of Abraham that sound ‘dualistic’. Until very recently, the exact same arguments were used to argue that St. John’s Gospel was Gnostic and that points to the problem. Not only is there ample example of that language in the Dead Sea Scrolls, for example, within the Second Temple period, but seeming synergy between the beliefs of a group and a text is not evidence that the group altered the text. That perceived synergy is very likely the reason why the text was popular with that group in the first place. Marcion saw certain elements within St. Paul’s epistles as consonant with his heresy. That doesn’t mean that St. Paul was a Marcionite, or that Marcion added those elements to the text, or that Marcion was interepreting those sections correctly.