It is common in the contemporary world to speak of Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism, and Islam as ‘monotheistic faiths.’ This categorization is intended to imply that, over against polytheistic religions, these three religious traditions have a similar view of God. Sometimes, this perceived similarity is taken so far as to argue that these three religious traditions worship the same God. Monotheism, as a term, refers of course to the belief that there is only one God. Polytheism, on the other hand, describes any religious tradition in which there are many gods and goddesses who are the object of worship and devotion. Less commonly discussed, and occupying a middle position between these two categories, is Henotheism, which is the view that there are many gods and goddesses, but one god in particular reigns supreme over all of them, with the others as his assistants or subjects. Another important term for this discussion is monolatry. A monolatrous religious tradition believes that many gods and goddesses may exist, but those of this particular religious tradition worship and serve only one.

It is common in the contemporary world to speak of Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism, and Islam as ‘monotheistic faiths.’ This categorization is intended to imply that, over against polytheistic religions, these three religious traditions have a similar view of God. Sometimes, this perceived similarity is taken so far as to argue that these three religious traditions worship the same God. Monotheism, as a term, refers of course to the belief that there is only one God. Polytheism, on the other hand, describes any religious tradition in which there are many gods and goddesses who are the object of worship and devotion. Less commonly discussed, and occupying a middle position between these two categories, is Henotheism, which is the view that there are many gods and goddesses, but one god in particular reigns supreme over all of them, with the others as his assistants or subjects. Another important term for this discussion is monolatry. A monolatrous religious tradition believes that many gods and goddesses may exist, but those of this particular religious tradition worship and serve only one.

While later Rabbinic Judaism, especially in the modern era, and Islam in general very neatly fit the definition of monotheism, Christianity has always been a bit of an outlier. Rabbinic Judaism and Islam teach that all other gods are false gods and that in truth only one exists and that one god which exists is a single personal being. Over against Christianity, the views of these two religious traditions are described as ‘unitarian monotheism.’ Christianity, of course, from the very beginning, as well as the diverse forms of Judaism in the ancient world, do not fit this definition so neatly. In the case of Christianity, this is first and foremost because of the worship of the Holy Trinity. While the term ‘Trinitarian monotheism’ has been coined to keep Christianity within the same category as these other two religious traditions, it is a category with only one member. Representatives of Islam and Rabbinic Judaism are quick to argue that Christianity is therefore not ‘really’ monotheistic. In their apologetics, they will often accuse Trinitarian belief of being some sort of compromise between monotheism and polytheism.

Likewise, many Protestant believers who do not accept traditional teaching regarding the saints and their intercessions will argue that this teaching is an accommodation of an otherwise monotheistic Christianity to polytheistic paganism. This is especially true regarding the hypothesized origin of the veneration of the Theotokos by those who have traditionally rejected it. This same instinct, that Christianity has been classified as ‘monotheism’ and therefore anything that conflicts with a certain understanding of monotheism must be rejected as a distortion of Christianity, gives pause to many of these same believers regarding the entirety of the doctrine and concept of theosis or deification. St. Athanasius’ statement that “the Son of God became man so that man might become God” becomes disturbing and must be explained away to make it comport with a pre-existing understanding of monotheistic Christianity.

This same discomfort has led to most English translation of the scriptures at best ‘clarifying’ and at worst concealing the way in which the term ‘god’ or ‘gods’ is actually used in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. Because this usage has been submerged in English translation, when it has been recovered by contemporary scholarship working in the original languages, it has become the grist for new theories regarding ancient Israelite religion. These retranslations are interpreted as some sort of deliberate attempt to conceal a non-monotheistic Israelite past. As these same scholars accept the characterization of early Judaism as monotheistic in the mode of modern Rabinnic Judaism, they posit evolutionary theories of ancient Israelite religion which begins with a polytheistic past and then, generally sometime in the Persian period, Judaism emerges as a form of unitarian monotheism. This characterization collapses at two points. First, it is not true that the many forms of Judaism of the Second Temple period believed and practiced unitarian monotheism. Second, it is an obvious point that for most of the history of Judaism and Christianity the text of the scriptures have been interacted with in their original and other very early translation languages which do not conceal the original usage and understanding of these terms. These scholars, then, are removing a coverup which never occurred and basic a hypothetical historical reconstruction on an imaginary change of belief.

The actual testimony of the scriptures does not neatly fit the categories of monotheism, polytheism, or henotheism. When their testimony is accurately described, however, they give a picture of the belief and practice of the communities from which they emerged which is coherent, and which is consistent with the teachings of Christianity regarding the Holy Trinity and the saints and their intercessions. There are two key elements required to understand the testimony of the scriptures regarding God and the gods. The first is the way in which various terms for ‘god’ or ‘gods’ are used in the text of scripture. The second is to understand the relationship between Yahweh the God of Israel and the other beings to which those terms are applied. The picture which emerges from the Hebrew Bible as understood within Second Temple Judaism is completely commensurate with that of the New Testament. This picture became the normative view of ancient Christianity while Rabbinic Judaism evolved in a unitarian direction largely in response.

The primary word group in Hebrew that is used for the term ‘god’ is el, eloah, and the plural elohim. This word group is related to ‘allah’ in the cognate language Arabic. The plural ‘elohim’ is used both to refer to Yahweh as a singular being and to refer to ‘gods’ plural. Which is the correct translation is determined primarily from context. There are clear places where it is a singular reference to the God of Israel, in particular when it is used in conjunction with the name Yahweh (eg. Gen 2:4-5. 7-9, 15-16, 18-19, 21-22). Elohim also frequently occurs as the subject of singular verbs, as in Genesis 1:1. In other cases, it is clearly plural either by context (as in Deuteronomy 5:7) or by being used with plural verbs. It must be noted that attempts to see within the plural of elohim an embedded reference to the Holy Trinity is misguided. There are instances in which pagan gods are referred to with the plural elohim (as in Judges 11:24; 16:23-24; 1 Samuel/1 Kingdoms 5:7; 1 Kings/3 Kingdoms 18:24). Likewise there are a number of passages in which elohim is used in the plural to refer to Yahweh the God of Israel, but the verb is plural (as Genesis 20:13; 35:7; 2 Samuel/2 Kingdoms 7:23; Psalm 58:12). Within the Hebrew scriptures, the grammatically plural elohim is simply more common than the singular eloah and is used both as a singular and a plural noun.

In addition to its use to refer to Yahweh the God of Israel, elohim is used to refer to other spiritual powers which were worshipped as gods. This is true in a negative sense, in commandments for Israel to worship no other gods besides Yahweh (as in Deut 5:7). Such statements are neutral as to the actual existence of these other deities and could therefore be interpreted along the lines of unitarian monotheism. Other statements, however, make it clear that the gods worshipped by the other nations do, indeed, exist. The most prominent instance of this is likely the repeated reference to Yahweh’s victory over the gods of Egypt (cf. Ex 12:12; 2 Sam/2 Kgdms 7:23). This is not a glorification of Yahweh for overcoming imaginary beings. One of these gods was Pharaoh himself, who obviously existed. The scriptures do not dispute the existence of these beings. Nor do the scriptures deny that the majority of the Israelites and later the Judahites fell to worshipping these beings. Throughout Israel’s history there are repeated commands to destroy shrines and images of other gods. These commands would not be issued if these shrines and images did not exist.

The initial locus of this characterization of Israel occurs in Deuteronomy 32:17. Deuteronomy 32 is written in a form of Hebrew far older than most of the Hebrew scriptures and therefore contains many words not used in the remainder of those scriptures. Verse 17 refers to the Israelites sacrificing to ‘shedim who are not God, to gods whom they had not known.’ The term ‘shedim’ is used in only one other place in the Hebrew scriptures, in Psalm 106:37 which speaks of the Israelites sacrificing their children to ‘shedim.’ The word appears to be an Akkadian word, ‘shedu,’ which refers to a spirit or god which protects a territory. They were typically represented by the Assyrians as bulls or calves. These territorial spirits are to be identified with the sons of God in 32:8 to whom God assigned the peoples of the world. Israel, however, belonged to Yahweh (32:9). In translating this text into Greek, the Seventy understood the sons of God in 32:8 to be angelic beings who later fell. They therefore translated the ‘shedim’ of 32:17 as ‘demons.’ The translation ‘demon’ is in keeping with the general Greek understanding at the time of the translation of the Septuagint, that the gods of the nations had been assigned to their territories in an ancient time by a most high god (as outlined, for example, in Plato’s Critias 109b-d and Laws 713c-e). The gods are here referred to with the term ‘demon.’ St. Paul shares this viewpoint, leading him to say that “what the pagans sacrifice they offer to demons and not to God” mimicking the language of Deuteronomy 32:17 (1 Cor 10:20; see also Psalm 96:5).

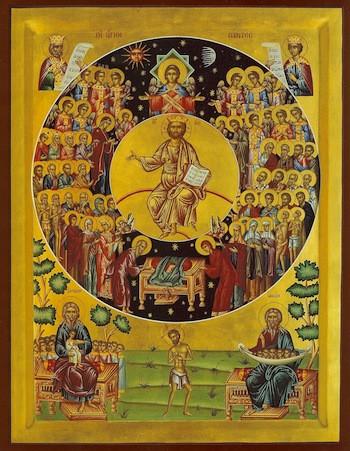

The word elohim is also used for other spiritual beings. One clear example is the medium at Endor referring to the spirit of Samuel as an ‘elohim’ (1 Sam/1 Kgdms 28:13). In the pagan religious traditions of Israel’s Canaanite neighbors, it should be remembered, the spirits of dead ancestors, particularly dead king, were the objects of ritual worship. This, then, is the Biblical understanding of what a ‘god’ is. A ‘god’ is simply a spiritual being. The understanding of the scriptures is therefore not monotheistic, at least according to the modern definition in that it does not deny that any gods other than the one Holy Trinity exist. At the same time, it is not properly henotheistic or polytheistic as it is monolatrous. These spiritual beings exist, but the people of God are not to worship or serve them. The spiritual powers who are loyal to Yahweh the God of Israel refuse the worship of human beings (eg. Rev 19:10; 22:8-9). The wicked spiritual powers seek to be worshipped instead of god (eg. Matt 4:9-10; Luke 4:7-8; Acts 7:42). God’s people are always commanded to, but are not always faithful in, worshipping and serving only Yahweh, the God of Israel, who exists eternally in three divine persons.

Nevertheless, these other spiritual beings, both angelic and departed humans who are righteous and faithful to Yahweh are called holy ones, sons of God, and gods by scripture. These are all beings who are members of Yahweh’s divine council, with whom he shares his rule over creation. While it is correct to say that Yahweh is ‘a god’, he is nonetheless fundamentally different than any other being in that category. He is eternal, other spiritual beings are not, and have their origin in his creative activity. He shares his dominion with them as they worship and serve him. They are capable of falling into sin and wickedness (Job 4:18; 15:15), he is utterly without sin. “Rejoice with him, O heavens. Bow down to him all the gods for he avenges the blood of his sons and takes vengeance on his enemies. He repays those who hate him and cleanses the land of his people” (Deut 32:43). “O God, your way is holy. Who is so great a god as our God? You are the God who works wonders. You have made your might known among the nations” (Ps 77:13-14). “For though there might be things called gods in heaven or on earth, just as there are many gods and many lords, but for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we are, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things through whom we are” (1 Cor 8:5-6).

You will know them by their fruits – Matt 16, 20

My sheep know me, hear my voice and follow me – John 10:27

God bless!

Fascinating reading Father. You should write a book someday. I would be in line to buy it, no doubts!

Thank you Father Stephen for taking this so many steps further than what I had been taught. You fill in many gaps. We know that Protestants do not believe in theosis, nor venerate Mary and the Saints. But in the context of monotheism as defined by the scholars, I can better understand why.

“monolatrous”….I just learned a new word.

“A ‘god’ is simply a spiritual being.”

But our God is set apart from all.

And He calls us to share in His rule over creation.

Now that is just unspeakably incredibly amazing that our God looks upon us like that. I know it is true, but I always stand in awe. I can only think of the Psalm verse “what is man that you are so mindful of him…”, well, all of Psalm 8, actually.

Thank you Father…your posts bring about many good reflections…

Father:

I liked the New English Bible version of your last scripture:

“For indeed, if there be so-called gods, whether in heaven or on earth – as indeed there are many ‘gods’ and many ‘lords’ – yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom all being comes, towards whom we move; and there is one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came to be, and we through him.”

Thank you for an enlightening post, as usual.

Fr. Stephen,

Thank you for another amazing post. The quotes from Plato were astonishing to read.

A question about Orthodox terminology about the saints and the kind of reverence we give them: I notice some hymns which suggest there is a sense in which we sacrifice to the saints. For instance, “To thee the Champion Leader do I offer thanks of victory” (my understanding is that depending on translation, the sacrificial connotation of “offer” can be emphasized more clearly – “offer/dedicate a feast of victory”, for example). How do you recommend we understand such language? I assume it is to be viewed in a way similar to the distinction between an attitude of worship and an attitude of veneration. Though this gets a bit confusing if worship is very closely connected to sacrifice (since then offering a sacrifice to a saint is harder to distinguish from worshipping the Trinity).

Thank you

The particular example you give is really playing upon the language of a victorious general returning from battle. So the language of the giving of laurels and the throwing of a feast in their honor is being picked up and utilized regarding the Theotokos. The real key here, though, is that there is one sacrifice which is practiced now in a literal, ritual sense in the church, and that is the Eucharist. The Eucharist is offered for the Theotokos, St. John the Forerunner, the saints of the day, and all of the saints, but is never offered to them. This is the core of the difference between Christian and Greco-Roman sacrificial practices. The Eucharist is a ‘memorial’ in the Num 10:10 LXX sense. While the pagans offered sacrifices to different gods and heroes on each calendar day, Christians offer the Eucharist on behalf of the various saints and other people living and dead who are commemorated on that day. This is made pretty clear, though often overlooked, in the anaphora prayers.

Fr. Stephen, thank you for clarifying – the for/to language is helpful. What you said about the Theotokos being compared to a victorious general returning from battle accentuates the fact that she is being put forward as a high example of our own victory in Christ, not put in the category of the uncreated God.

I know there are mysteries here and language will fail us at some point. But would you say it is safe to say that because the Eucharist is offered “for” us and “for” them, that we should therefore think the saints in glory somehow benefit and are further exalted by our own participation in the sacrifice of the Eucharist? Hebrews 11:40 comes to mind.

So, would it be correct to say that the “Allah” that the Muslims worship and the “God” of Rabbinic Judaism are demons masquerading as the God who rules over all?

And I’m trying to wrap my head around how this relates to St. Paul at the Aeropagus (Acts 17) proclaiming to the Greeks the Unknown God “whom you worship without knowing” (v. 23)…

Any helps with this Fr. Stephen?

It is a trope in Second Temple Jewish literature and some of the early Fathers that demons sneak in and receive the worship given to anything other than God. So your first line of thought has a good pedigree. For evangelistic purposes, that isn’t where I would lead off. I would probably use an approach more similar to St. Paul’s in arguing that they are attempting to worship and follow a God whom they don’t know, because he can only be known in Jesus Christ. So, I think in terms of Acts 17 that is where St. Paul is going. Though angered by their idolatry, St. Paul sees that they have this shrine which acknowledges that there’s a God out there somewhere whom they don’t know. From St. Paul’s perspective, this is true: there is a God out there whom they don’t know, but whom St. Paul is prepared to proclaim to them. His language in the sermon he then preaches is aimed not at arguing that Yahweh, the God of Israel exists, but that he is superior to and categorically different than all of the other gods with whom they’ve interacted in the past.

Wow, Fr. Stephen, this was so helpful! “Monolatrous” – I just learned something new! This made so much sense!

Your post is enlightening but I can’t figure out how to interpret Deuteronomy 32:39 “There is no elohim besides me.”, which agrees with Isaiah 45:5: “I am Yahweh, and there is no other. There is no other elohim besides me.” and other Isaiah texts.

It seems to me that, depending on the passage, the Bible claims that elohim different from Yahweh exist or don’t exist. What are your thoughts?

The examples you cite are statements of Yahweh’s uniqueness, not statements regarding the ontology of the other beings worshipped as gods by the nations. The position of the Old Testament is that Yahweh belongs to the category ‘Elohim’, but that no other members of that category are comparable to Yahweh. This is true for a number of reason, chief among them that Yahweh created the others and they are dependent upon him. So individual statements in the OT will be addressing at least one or the other part of this overarching view. Statements like, “Who among the gods is like Yahweh?” address them both. Deuteronomy 32:39, for example, isn’t saying that angelic and demonic beings don’t exist or that the disembodied spirits of the dead don’t exist (these would be the other things called ‘elohim’ in the OT). Rather, it is saying that none of them are ‘beside’ Yahweh, none of them are parallel to him. None of them compare to him. Reading the context, when the time comes for Yahweh to judge, none of them will be able to protect the people who have been worshipping them. Likewise, Isaiah 45 is Yahweh speaking to Cyrus. In the context, he is condemning Cyrus for having given the worship and praise due to him to Ahura Mazda (and his shadow) in terms directly drawn from Persian religion. It is Yahweh, God of Israel who has placed Cyrus in his position of power and controls his destiny, etc. not Ahura Mazda or any other spiritual power.

The word ‘elohim’ in Biblical Hebrew simply refers to a spiritual being. No one in the ancient world, including ancient Israel, though that spiritual beings didn’t exist in multiplicity. The disagreement is over which ones have power and which are worthy of worship. THe disagreement is over what in the visible world is the result of the actions of which spiritual beings.