As is the case with 4 Ezra, 4 Maccabees is a Biblical text that lies at the very edges of the Old Testament canon in the Orthodox Church. In later Greek manuscripts, 4 Maccabees is included in an appendix. In older Greek manuscripts no such distinction is made, though 4 Maccabees is often found at the end of these manuscripts rather than following 3 Maccabees, along with Psalm 151 and the Prayer of Manasseh, two liturgical fragments. It is present in Old Georgian Old Testaments and was for a time, though no longer, in the Romanian Old Testament. Due to their relegation to the ‘apocrypha’ in most English Bibles, 1-3 Maccabees are not well known to most English readers. 4 Maccabees is therefore even less so.

As is the case with 4 Ezra, 4 Maccabees is a Biblical text that lies at the very edges of the Old Testament canon in the Orthodox Church. In later Greek manuscripts, 4 Maccabees is included in an appendix. In older Greek manuscripts no such distinction is made, though 4 Maccabees is often found at the end of these manuscripts rather than following 3 Maccabees, along with Psalm 151 and the Prayer of Manasseh, two liturgical fragments. It is present in Old Georgian Old Testaments and was for a time, though no longer, in the Romanian Old Testament. Due to their relegation to the ‘apocrypha’ in most English Bibles, 1-3 Maccabees are not well known to most English readers. 4 Maccabees is therefore even less so.

The four books of the Maccabees differ in genre, type, and contents though they stem from events in the same general era. Following the death of Alexander the Great, his successors, known in Greek as the ‘diadochoi’, went to war to carve up his empire amongst themselves. The Greek imperial powers who therefore ruled portions of the world were by nature hostile to the Jews, who at this point in history, the 3rd through the 1st centuries BC, had major centers in Judea, Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch in Syria, Mesopotamia, and were scattered throughout the known world in smaller communities. Because the Jews refused to worship the gods of the Greeks, they were seen as traitors. The sacrificial rituals of the Greeks were civic acts in which the entire polis participated. They bound the community together and bound them all together with their gods. When misfortune befell a pagan Greek community, therefore, and it intuited that they had the gods’ disfavor, those who refused to perform the rites due to the gods were an obvious target for blame. The books of the Maccabees describe this persecution and its results.

3 Maccabees is the odd man out among the books of the Maccabees in being set in Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Greek dynasty which ruled Egypt until Cleopatra. It describes persecution faced by faithful Jews living in Egypt, particularly in and around Alexandria, during the late 3rd century BC. These events take place a few decades before the events of the other books of the Maccabees. 1, 2, and 4 Maccabees all deal with the oppression of Judea itself by the Seleucid dynasty in the early 2nd century BC. This Greek dynasty which ruled from their newly established capital, Antioch on the Orontes. Following a disastrous battle against the Ptolemies in an attempt to expand his empire south and west, Antiochus IV Epiphanes returned to Jerusalem. He blamed his military failure on the failure of the Jews to honor the gods and so entered the temple in Jerusalem, rebuilt after the return from exile, and sacrificed a pig there to Zeus. This was known to the Jews as ‘the abomination which causes desolation’ and is mentioned and alluded to frequently in the latter parts of the Old Testament and in the New Testament. This act defiled the temple and made it unfit for its intended use in worshipping Yahweh the God of Israel. There had already been incredible pressure upon the Jewish people to conform to Greek culture and religion, to which many had given in. This persecution intensified at the hands of Antiochus after the desecration of the temple.

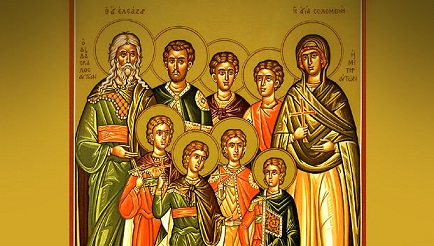

1 Maccabees describes, in a straightforward historical account, the revolution that proceeded to unfold. Judas Maccabeus, which means ‘Judah the Hammer’, and his brothers took the atrocity in the temple as the last straw and raised up a revolutionary army to overthrow the Greeks. They were successful and established an independent Judea, making treaties with Sparta and Rome for defense to prevent the Seleucid’s potential counter-attack. Judah and his brothers established a new monarchy, the Hasmonean dynasty, with a family member also made a high priest. The Sadducean high priestly families encountered in the gospels are descendants of these men, and not of Aaron or Levi. After their victory at the battle of Emmaus, the temple was rededicated and brought back into service. The anniversary of that rededication became an annual feast, now celebrated as Hanukkah by Jewish communities. 2 Maccabees covers the same time period, but gives a more personal portrait of individuals who suffered for their faith at the hands of the Seleucids. The most celebrated of these, whose story is told in some detail in 2 Maccabees, are the 7 Maccabean martyrs, their mother, and their teacher St. Eleazar. These martyred saints are celebrated in the Orthodox Church on August 1.

4 Maccabees is another genre entirely, following the form of a philosophical treatise or Old Testament wisdom literature. In reality, it is most likely a melding of the two, written by a Jewish person of Hellenistic background at the end of the 1st century AD. The text also has features of a homily or oration, focusing on the lessons in virtue to be learned from the example of the Maccabean martyrs. Due to some of the details contained within the book and the traditions reflected there, it was likely written in the city of Antioch in Syria. The relics of the Maccabean martyrs were kept in a shrine, first Jewish and later Christian, in the city of Antioch from the time of their deaths until the collapse of the ancient city at the turn of the 15th century. Before their commemoration as Christian saints, these martyrs were commemorated in Jewish synagogues with a day of fast in the 9th of Av. The composition of 4 Maccabees was likely related to the prominence of the martyrs in the Jewish community of Antioch in the first century. There was a belief for a considerable period that it was written by Josephus, the Jewish historian. In fact, during the period in which this text was included in Romanian Bibles, it appeared there under his name. It has, however, since been thoroughly disproven that the works of Josephus and this text were by the same author because of contradictions not only in grammar, style, and vocabulary but also conceptual contradictions.

The book of 4 Maccabees can be roughly divided into two halves. The first half takes the form of a treatise on reason or wisdom. The central theme of this introductory portion is on the superiority of reason (logos or logismos) to the passions (pathe). Reason exists as an overarching category and is a power of the soul that allows it to resist, overcome, and tame the passions which express themselves through particular desires. Reason is an overarching category which has a real presence in the world and is described by the Torah. Within the lives of individual people, reason takes the form of wisdom which produces virtues. These virtues are continually assailed by desires which themselves ultimately stem from the passions. For the author of 4 Maccabees, wisdom and understanding of the creation in which we live, and the creation which we are, reinforced the truth of what is communicated in the Torah and produces the virtues that allow persons to resist temptations and overcome the passions. He gives many Old Testament examples throughout this portion of the text, such as Joseph’s flight from Potiphar’s wife.

There are clear and direct lines of continuity from the first portion of this text to Orthodox monastic literature. The understanding of sin as passions and passions expressing themselves as desires which give rise to temptations is present in both. The necessity of cultivating particular virtue through the keeping of commandments which are themselves reinforced by spiritual insight is described here clearly. The author of 4 Maccabees discusses the need to sift one’s thoughts. Thought cannot be prevented from entering the mind, but can be cut off before they are able to take root. Here also are found the beginning, in the understanding of the ‘logos’, of the connective tissue between the Word of God in the Old and New Testaments and the understanding of the ‘Logos’ and the ‘logia’ in St. Maximus the Confessor. 4 Maccabees therefore represents an important link in the chain connecting the wisdom literature of the Old Testament to the monastic wisdom which has come to so characterize the mind of the Orthodox Church.

The second major section of 4 Maccabees is an extended meditation on these themes from the example of Eleazar, the seven Maccabean martyrs, and their mother. In praise of these martyrs, the author of 4 Maccabees retells the story told in 2 Maccabees but in an even more dramatized form. Eleazar was tortured to death first by the Seleucids in an attempt to get him to violate the Torah, specifically by eating pork. Pork was a major part of the Greek staple diet, but pigs were also the animal that was most commonly sacrificed to the Greek gods, so the pork being offered here had presumably also been offered to idols, adding the sin of idolatry to ritual uncleanness. After his death by torture, the seven martyrs are tortured to death in turn in front of their mother, both to try to get them to reject the Torah, and their mother to do the same. Their mother, however, encourages them on to bravery and after her sons, she is also tortured to death.

Reflected in this narrative in 4 Maccabees is the Second Temple Jewish understanding of martyrdom in its fullest form. All of the elements that will come to characterize the literature of early Christian martyrology at the beginning of the 2nd century are present here revealing another point of continuity. The heroic resistance of the martyrs to the denial of their faith, the characterization of their tortures as a struggle or contest over which they are victorious by being willing to go to their deaths, the urging of close family members and friends not to save themselves by denial but to endure even unto death are all present. The way this story is related also helps us understand the vehemence of St. Paul before the road to Damascus, and which he himself faced after that experience, regarding the provisions of the Torah down to the level of what should and should not be eaten. Within the living memory of the people to whom St. Paul was preaching, their forefathers and heroes in the faith had been willing to lay down their lives over these very issues.

Even more importantly, however, within the Second Temple Jewish understanding of martyrdom as expressed here in 4 Maccabees we gain important information about how first century Jewish believers would have understood a sacrificial death. While human sacrifice was always expressly forbidden as an abomination, there was within Second Temple Judaism, largely developed concerning the martyrs of the Maccabean era, the idea that one could, through a faithful death, offer one’s life as a sacrifice to the God of Israel. In 4 Maccabees 6:27-29, Eleazar, as he dies, prays, “You know, O God, that though I might have saved myself, I am dying in burning torments for the sake of the law. Be merciful to your people, and let our righteousness suffice for them. Make my blood their purification, and take my life in exchange for theirs.” Both the element of sin offerings in the Old Testament, the idea that the sacrifice was offered as a ransom for the offerers life, and the idea of atonement, of purification from and the wiping away of sin, are present in this understanding of St. Eleazar’s death. When Jewish believers of this period were told of the sacrificial death of the Messiah, 4 Maccabees describes for us the lens through which they would have understood this.

Thank you for this fine review of information of which I had been clueless.

My understanding is that Orthodoxy does not accept substitutionary atonement, much less penal substitutionary atonement, so how does the OT/Second Temple understanding of atonement and sin offerings factor into the Crucifixion and what Christ exactly accomplished on the Cross? (I’m a former Lutheran/Evangelical becoming Orthodox, so I apologize if I’ve mistaken something or not explained my confusion well.)

Its a misnomer that Orthodoxy doesn’t accept substitutionary atonement. Western theology has for a few centuries now dealt in ‘theories of the atonement’. The problem with this concept is that these theories are seeking, to quote New Testament scholar Simon Gathercole, a ‘mechanism’ by which atonement takes place. This reduces the sacrificial death of Christ to some sort of mechanical transaction, which might help in the construction of a detailed theological system, but doesn’t bring us closer to Christ. Penal substitutionary atonement in particular is problematic for this reason. In its full-fledged form, it is a Calvinist doctrine, because it only works if you believe in either limited atonement or universalism. More crucially, though, there is nothing anywhere in the Old Testament sacrifices to which Christ’s death is compared which contains any aspect of penal substitution. This is an overarching problem with Reformed theology. The New Testament is interpreted based primarily on logic and Greek linguistics, and then the theological conclusions which come from it are projected back into the Old Testament although they don’t well fit. All of the various ‘theories’ of the atonement are really, and began in earlier Christian writers, as analogies to understand some aspect of Christ’s atoning death. None of them is a complete picture, let alone a ‘mechanism’ by which salvation takes place.

I apologize if all of that is a little obtuse, but to get down to more brass tacks in terms of the way the scriptures and the Fathers talk about Christ’s atoning death. The most common comparison made regarding Christ’s death and resurrection in the scriptures is to the Passover. That’s why we still call the celebration of his resurrection ‘Pascha’. There is no penal substitution in the Passover ritual. There are three main elements: Manumission from slavery, the defeat of powers hostile to God, and the marking out of a people with blood. These are the three elements focused on throughout the New Testament and the Fathers. Just as the God of Israel defeated the gods of Egypt, including Pharaoh, and freed his people from slavery to them, so also Christ through his death has defeated the evil powers which had held the world and its people in slavery through the power of sin and death. Slavery in the ancient world was a function of debt. Christ ransoms the lives of humanity from death. Death has a claim on every human being through sin, and so any given human person can only die for their own sins. Christ owed no such debt and so death had no such claim, so he was able to voluntarily lay down his life to destroy death and grant life to the world. Finally, through Christ’s death, a new people is marked out, just as the blood on the lintels marked out what would become the nation of Israel in Egypt.

4 Maccabees shows the beginnings of some of these ideas. Specifically, St. Eleazar puts into words the idea that because he is being tortured and killed not for having done evil or committed some crime, but for the sake of righteousness, that he can offer his death as a sacrifice to God for the sake of his people. There is no idea here that God is the one torturing and killing him. Rather, he is offering up his life in the same way that animal sacrifices were offered to the God of Israel, in the hope that they would be a pleasing aroma to him.

Father Stephen,

Another excellent post. Thank you.

If I may, I have a question…

Regarding ‘the abomination which causes desolation’, you remind us that this is again mentioned in the NT . You also say: “This act defiled the temple and made it unfit for its intended use in worshipping God”. When Jesus mentions it in Mt. 24 and says: “Therefore when you see the‘abomination of desolation,’ spoken of by Daniel the prophet, standing in the holy place” (whoever reads, let him understand)…”, wasn’t Daniel prophesying about Antiochus IV Epiphanes? If so, Jesus speaks as if this will be a future event, when it actually had taken place hundreds of years before. I’m thinking His words “(whoever reads, let him understand)” may point to what you said about the act of Antiochus which defiled and made unfit, worship in the temple. And that Jesus wants us to understand that certain acts – past, present and future – will defile. For us the temple is God’s presence in not only the Church building, but is Christ Himself, and our bodies sanctified in Him; therefore, all forms of willful rejection of Christ and sins against our body are, to God, an abomination that causes desolation, that is, it renders the “place” inhospitable to the Spirit of God. Additionally, as for the ‘Church building’, when Jesus spoke these words, His crucifixion was soon to come to pass, and that ‘Temple’ was to be raised from the dead forever more. This, the people, including His disciples, did not understand either.

Now, do I understand this properly?

Also I would like make a comment in relation to Brittany’s question about sacrifice and atonement. In your previous post you referenced Heb. 9: 15-28. There, several verses got my attention:

“(15) And for this reason He is the Mediator of the new covenant, by means of death,

for the redemption of the transgressions under the first covenant…”

It goes on to describe how Moses sprinkled blood on ‘the book, vessels, and all the people’. And then vs. 22: ” And according to the law almost all things are purified with blood, and without shedding of blood there is no remission.”

In your post “The Sacrifice to End All Sacrifices” you well correct our misinterpretation of the meaning of sacrifice, and explain that it is not the killing in and of itself that appeases God, but rather a giving thanks in offering our firstfruits. But still, I lingered with the question ‘why the blood’? The blood is a significant aspect these rituals. Then you go on to say it is a means to purify , to cleanse, and you tie it into Christ’s atoning once for all sacrifice:

“… in the eating of Christ’s body and the drinking of his blood , we come to participate ever more fully in that once and for all sacrifice, and to receive in ourselves…the effects of that sacrifice, namely , purification from sin and the life of God himself. ”

This was one of those very satisfying light-shedding moments!

I find it quite interesting how much time it takes for the mind, our thoughts, to be rearranged, to be re-established, re-set and fixed into thinking properly about these profound truths! It takes time – prayer, study, contemplation – in our search for truth. Then there finally comes a time when you begin to see ‘the light’. I have thought about ‘why the blood’ for years! and just never got the answer. I was taught that because of the Father’s wrath toward us in our sin, He substituted His Son in our place, to vindicate and justify His righteousness. Growing up, it was painful to be among people who believed this way. An inordinate amount of punishment was justified. It was impossible to come to terms with.

It is a blessing to have come home to Orthodoxy. Your teachings came at just the right time for me, as they blend in smoothly with what I have learned and experienced up to this point. I am very thankful for your work. The clarity in your writing and the topics cover has opened many doors and has been a joy!