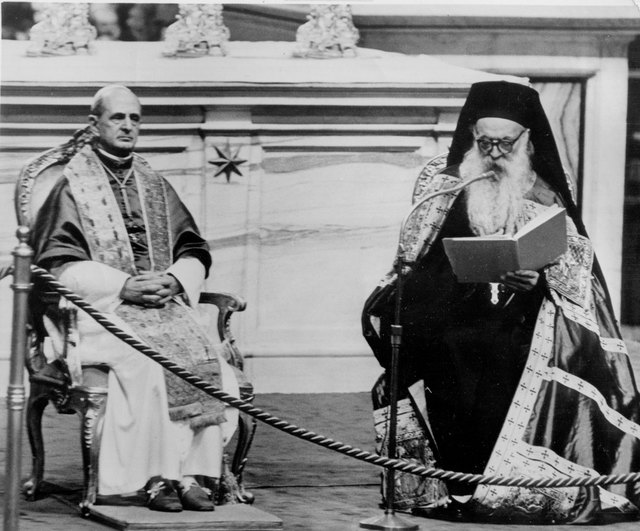

Upon his election to the chair of bishop of Rome in March of this year, Pope Francis announced his intention for a personal meeting with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople in the Holy City of Jerusalem for the coming year of 2014. Although the trip has not yet been confirmed, the event is intended to commemorate the meeting of Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI on the Mount of Olives in January 5-6, 1964.

The 1964 encounter in the Holy Land was a significant development. The first physical meeting of a Roman pontiff and a patriarch of Constantinople since the failed 15th century union council of Florence, this Jerusalem summit led to the Catholic-Orthodox Joint Declaration of December 7, 1965. In this declaration, read simultaneously at a meeting of the Second Vatican Council in Rome and at a special assembly at the Phanar in Istanbul, the 11th century anathemas between the churches of Rome and Constantinople were lifted simultaneously by both sees, and a sincere desire for ecclesiastical concord was expressed. The first in a series of similar reconciliatory gestures, the “dialogue of love” begun by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras would soon lead to a bi-lateral theological dialogue on multiple levels, international and local, pursued with increasing seriousness up to the present.

These developments have continued to provoke a conflict of responses among the Orthodox ever since, ranging from enthusiastic embrace, to cautious, patient and discriminating commitment, to distrust, indignant denunciation and opposition. Now, with the news of a possible recapitulation of that first meeting in Jerusalem, the moment is propitious for reflection on a half century of ecumenical dialogue between Orthodoxy and Rome.

Father Georges Florovsky spent his entire service of over five decades as an Orthodox theologian intensely involved in ecumenical dialogue. His person and work continues to command respect from all corners of the Orthodox spectrum of opinion, from career ecumenists to resolute anti-ecumenists and everything in between. In early discussions at the WCC central executive committee meeting in Rhodes in the summer of 1959, Father Florovsky strongly supported a bi-lateral international dialogue between Orthodox and Roman Catholic theologians, while also resisting what he saw as the attempt of the WCC leadership to control the dialogue. His opinions on this dialogue, however, were rarely publicly expressed. It is therefore of great interest and value to learn his thoughts in this matter, offered on the occasion of the 1964 Jerusalem meeting. The present text we now introduce was originally published in Russian: Georges Florovsky, “Знамение Пререкаемо,” Вестник Русского Студенческого Христианского Движения, nos. 72-73, I-II, 1964, pp. 1-7. It has never appeared before in translation. It is also not cited in the existing scholarship on Florovsky or on the ecumenical dialogue. We offer the text now both for its historical interest and in the conviction that Father Florovsky’s sage and balanced counsel still remains relevant and worthy of consideration for today.

– Matthew J. Baker, November 2013

A Sign of Contradiction

Georges Florovsky

He calleth to me out of Seir, Watchman, what of the night Watchman, what of the night? The watchman said, The morning cometh, but it is still night. (Isaiah 21:11)

The meeting of two patriarchs – the new and the old Rome, long separated from each other – certainly was a significant event. And the venue, chosen deliberately – the holy land, a country of great promise, the country of the accomplishment of the sacred memories, the country of Christ – it gave to the event a very solemn, even symbolic, character. Some perceived it as a miracle.

The importance of the event is obvious. It is not so easy, however, to unravel its full meaning and to determine its value. In any case, the meeting of the patriarchs was an unexpected event, almost a surprise. Few were prepared for it inwardly, psychologically and spiritually, even among those who were ready to welcome it sincerely. Therefore, as soon as it was talked about, there were misunderstandings. Some embraced it with joy, as a favorable sign. For others it is deeply troubling. Among many Orthodox, this meeting caused alarmed and suspicion, made them wary and plunged into passion and fear. This could and should have been expected, and to remain silent about it now it would be foolishness. The topic of Rome is a painful topic for the Orthodox. Too many painful memories, disappointments, bitterness are connected with it. To account for that past is not easy, and it is hardly likely that it could be accounted for. Sober historical memory is a necessary guarantee of responsible action. Only the memory should not be binding. One cannot act only on historical precedents. History does not only repeat itself. History is still going on. What was impossible yesterday might become possible tomorrow. Conditions are changing, and are changed by people. The horizon can be shifted. New possibilities may always open up.

Strictly speaking, from the Orthodox point of view, the topic of Rome is the chief and principal ecumenical question. Here exactly is the beginning of “Christian division,” the tip and the root of “schism.” In a certain sense, we may be right to speak of the “undivided” Church of the first Christian millennium, although there was division then also. The image of “one Church,” however, stood firm in the Christian consciousness of the time. The “divided Church” – if this careless and ambiguous expression should be used at all – begins with the break between Byzantium and Rome. The unity of the Christian world was broken precisely then. This was the central catastrophe or tragedy of Christian history, in its universal perspective. The history of this break has been described many times, and from different points of view. A completely impartial image of this sad history is difficult to achieve. It was very much the result of a misunderstanding, a matter of human frailty, stubbornness and sin. Probably the division could have been avoided. In fact many for a long time refused to believe it. History is composed of human decisions, it depends on human freedom, sometimes greedy and often blind-sighted. Events, of course, could have proceeded differently. However, now we are facing the reality of accomplished separation, and reference to unrealized possibility does not solve our current problem. Is it possible to restore the lost unity, and to strive for this? Or, alternatively, should one be reconciled to the separation as final and irreversible, and read any attempt to “reunite” as hopeless and rather dangerous? Historical examples suggest, it seems, the most pessimistic answer. In fact, all the attempts to fix the “separation” were clumsy and hasty reunions, and the memory of them is a heavy stone in the mind and heart of the Orthodox. Does this mean, in the final analysis, that it is necessary to give up all hope and retreat into disconnection? Do I need to reject any glimmer of hope with distrust and suspicion?

Several years ago, in 1950, Professor Ioannis Karmiris spoke at the celebration of the Three Saints, at the University of Athens, on this subject: the schism of the Roman Church. His speech was devoted to the history of the separation. He concluded by raising the question, whether reunion is possible? Despite all the sad lessons of history, he emphasized, the peaceful resolution of the disagreements between the Orthodox Church and the Roman Church is entirely possible – under certain conditions, “by economy.” The separation should not be considered final and insurmountable. On the contrary, it must be overcome and can be overcome. Only this will require, above all, a long and serious training in the hearts and minds of both Churches, including both clergy and the laity. The Orthodox Church, Prof. Karmiris was convinced, should not shy away from collaboration with Rome in this direction, to coordinate existing differences soundly “by way of economy” and to restore harmony, love and unity between the two Churches.

This judgment of such a careful and discreet theologian and historian as Professor Karmiris requires serious attention. It is not entirely clear how he understands the “way of economy.” In any case, he did not think that “reunification” can take place without a substantial “agreement,” without addressing controversial issues. Only he believed that these issues, with the good will of both parties, may be resolved. In fact, he invites both Churches to a responsible theological dialogue – based on the Word of God and the ancient Tradition of the Church, and in a spirit of mutual attention and love. One must not expect such a dialogue will be easy and lead to quick resolution of all controversy and doubt. On the contrary, one must anticipate that it will be lengthy and difficult, if it is to be honest and deep. But this is not a sufficient reason to refrain from it, or to avoid it. The main obstacle to ecumenical progress is always just ecumenical impatience, ecumenical hastiness. And it always will tend towards the simplification of problems. The history of relations between Orthodoxy and Rome in the past demonstrates the danger of such haste, and its futility. However, under present conditions the dialogue may be easier than even a few years ago. The Roman Church is now in the process of reviewing her theological tradition, and in many ways returning to the tradition of the Ancient Church. This creates conditions favorable for meeting.

The dialogue is primarily a meeting. In many circles – both from the side of Rome and among the Orthodox – there is now a real will to meet. Meeting has already occurred by distance – in the theological literature. We must first of all get to know each other. The problem of mutual familiarization must be put in all its breadth. Most fruitful of all would be joint study and discussion of the main themes of the Christian faith, based on the Word of God and in the context of the Tradition of the Church. This would be the beginning of the “preparation of the hearts and minds,” mentioned by Professor Karmiris. The problem of separation must be put in all honesty. And this will inevitably discover that the very meaning and nature of the division is understood differently in Rome and in the Orthodox Church. Therefore, the question of “reunification” is posed differently. This does not mean however that the first task of the dialogue must necessarily be the topic of “reunification” as such. This topic will arise of itself in the process of dialogue. To begin there would have been premature. It is necessary first of all to make sure that the “reunification” is a real and not an artificial task, that the very being, the very nature of the Church requires it. The phrase, which is now so often abused – separated brothers – will be filled with a living meaning only then when it is experienced as an acute pain of separation, sorrow over separation, when the depth and reality of the schism is identified.

The method of theological dialogue can only be ecumenism in time. A true meeting of the divided East and West is possible only within the element of Church Tradition. The futility of the method of “comparative theology” has long been exposed in the broad experience of the ecumenical movement, and this method has already been abandoned. We must return to the sources. “Ecumenism in time” does not mean, however, retreat to antiquity, it does not mean a simple return to the past. Tradition in the Church is something more, and something different, than just memory, than just remembrance. Meeting in Tradition is not a restoration – “restoration” is always violence to life.

In any case, we cannot just go back to the year 1054 and recreate the questions of those days. East and West have changed since then, and there now stand other questions. Christian Tradition was divided in history. Now the task will be to restore its unity and completeness. That should be the task of theological dialogue. Meeting in Tradition is a mutual and joint dwelling in the fullness of Tradition.

And another way to real reunion, there is none.

Such a broad program will seem to many impractical, unrealistic, and too “academic.” For its implementation will require, obviously, a lot of time and a huge mobilization of forces. Is it possible to solve the problem more easily? In broad ecumenism, movements have long been talking about immediate “intercommunion” as the method of solution: should we not start just with “communicatio in sacris,” that is, in the Eucharist, and postpone theological dialogue? Is it necessary, in fact, to strive toward a real unity in faith, outside of a formal agreement on some conventional minimum, for example, the Nicene Creed, with the full freedom of interpretation, and only this minimum? In a strange way, this method is sometimes proposed today to address the problem of reunification of Orthodoxy and Rome. True, “minimum” here is taken in a much more robust and wider sense, but still with an uncertain interpretation of freedom – apostolic succession, sacramental hierarchy, the mysteries, a common symbol of faith. Should we not start with the resumption of Eucharistic communion between the separated Churches, Orthodox and Roman, with no further “harmonization” in the doctrine of the faith? Strictly speaking, the method is not new – it is the method of the Unia. The sterility and the ambiguity of this method has long been revealed in historical experience, but strangely it is still echoed now, albeit in a new and subtle way. Unia does not provide a real unity. What is achieved is only the appearance of formal unity, but the “reunification” of one part to the other does not coalesce. Pragmatism and relativism are introduced into the realm of faith, a certain kind of indifference, on the pretext of theological pluralism. Unity in faith, of course, does not require uniformity in theology. A certain freedom in theological interpretation remains, but under the condition of the living and organic conjugation of those things which are interpreted. Of course, we must strictly distinguish between levels: dogma, doctrine, theology. The distinction is not so easy to hold, in fact, for all levels are related to each other in the unity of ecclesial consciousness. In any case, in the dogmatic realm, there can be no room for pluralism. Strictly speaking, such a formal scheme of “reunification” under current conditions is unacceptable because spiritually and psychologically it is hopelessly out of date, besides the fact that it is spiritually wrong. For our time, thank God, is characterized by theological awakening, a new sensitivity to matters of faith, the search for the living fullness. Of course, this awakening has not embraced the whole of the Christian world. It must be hoped that, with God’s help, it will break forth. In this regard, theological dialogue may play the role of a kind of ferment.

No doubt, the very fact of the meeting of two patriarchs – and it is already one thing, that it was made possible – speaks of the desire for unity. But what kind of “unity” is in question? From the Orthodox side, a wish was initially expressed to bring to the meeting Palestinian representatives and other Christian confessions, to make it, so to speak, completely “ecumenical” in composition. This did not materialize. Apparently, the Vatican had in mind only the meeting of the two patriarchs. This limitation has profound ecclesiological sense. On the other hand, what was supposed to be discussed: “union” or “unity”? The distinction between these terms may appear artificial and arbitrary. However, it has recently been insisted upon openly in some Orthodox circles, with the purpose of stressing that “Christian unity” is possible without “union.” This is not just a question of terminology. The distinction of terms means a division of tasks. Under the name of “Christian unity” is implied in this case “collaboration,” cooperation in practical schemes. It does not necessarily require “harmony” and “unity” in the faith, except in very general terms. Then the participation of other confessions is logical and desirable. In the dark and troubled conditions of our time, this desire to create a sort of uniform “Christian front” for direct action is understandable. And one can even sympathize with this desire. Nevertheless, it is necessary to make at least two substantial reservations. First of all, it is not surprising that in today’s environment the emphasis is often is transferred to the opposition of “belief” and “unbelief” – it is a burning contemporary theme. But often there is a tacit, but no less dangerous, substitution of “religion in general” in place of Christianity, and the content of the faith pushed into the background. In this perspective, differences between separated Christians lose their practical importance, and the question of unity of shifts and is reduced to the psychological or the political plane. In reality, the power of Christian unity is just the unity of faith, within the Unity of the Church. In the second place: no matter how desirable Christian “cooperation” in a certain sense and to a certain extent may be, it does not lead to a real unity, and it even overshadows the very theme of “unity” – in the One Church. Strictly speaking, Christian “cooperation” is, in the final analysis, an inevitably ambiguous undertaking. “Cooperation” may only serve the cause of Christian unity only when it is inwardly subject to the search for “unity”, that is, Unity in the Church. Otherwise, it can easily lose its distinguishing Christian character and become a hindrance to “unity.” And this danger is very real.

The Palestinian meeting of the Patriarchs – of the new and the old Rome, for a long time and still divided – is, in any case, a timely reminder, and a double reminder – of the fact of separation, and of the task of unity. A reminder and a call . . . This is only the beginning of the way. And, in the apt expression of St. Basil the Great, “the beginning of the way is not yet the way.” The question now is how the voice of the Church will respond to this reminder and call. The subject of Rome is once again put on the order before the Orthodox consciousness. For some, Rome is a Church, even though a “separated Church.” For others, Rome is simply not in the Church. Strictly speaking, there is a similar disagreement also among Roman theologians, with a variety of nuances. This question requires a thorough theological development. The question of Rome is an ecclesiological question.

Orthodoxy in our time is strongly called to theological work. And only in this will be revealed the universal nature of Orthodoxy.

“The watchman said, The morning cometh, but it is still night.”

Cambridge, Mass.

I’m not sure that I understand what Fr. Florovsky is saying that anyone else of much less intelligence and theological insight couldn’t say. He just does it in many and fancy words here. In other words, what is his practical solution? I found myself saying “Yes, yes, yes, … so what are we going to do?”

It seems to me that ultimately it is God who establishes unity and that the path to unity is not through theological discourse but through conversion and repentance – through a participation in His Oneness. Only through purity of heart does one see the path to this unity and only through the healing of internal division brought about through our sins will the external divisions be healed as well. The emphasis in such discussions always seems to neglect the ascetical life.

I cannot speak for Florovsky, but I can at least speculate that he would see genuine theological dialogue as being a necessary step in the process of conversion and repentance. If two parties do not believe the same things, then to what, exactly, are they being converted? All askesis has a goal, and if the goals are not shared, then asceticism will not magically produce unity in faith.

To put it in specific terms, if the Orthodox and Rome are not preaching the same faith, then calls to repentance will not bring them closer together. They have to be repenting toward (not just repenting of) the same thing.

This, I think, also would answer Luke’s objection above. If we do not have the same theological vision, then there is little that we can “do.” Unity in dogma and doctrine has to come first. That is certainly the witness of the ancient Church, as well.

Perhaps I am not understanding the thrust of your comment. That doesn’t seem consistent with the Eastern understanding of asceticism or theology. The whole aim of asceticism is to capacitate a person for prayer and the highest experience of this prayer is theology. It is knowing the Trinity or as in patristic sense of an experiential way of union with God. This theology is a kind of knowing that requires a deep change in mind (nous) of the knower and such a change is ascetical.

The article already seems to acknowledge the tenuous nature of theological dialogue in the sense of focusing on doctrinal differences. In fact, it notes the failure of it over the centuries.

You ask “who do they repent toward?” They repent toward God – He who is Truth, He who is Unity. Asceticism capacitates for participation . . .

There is no Eastern theology of ecumenical engagement. So what you are referring to is rather the internal theology of salvation for the Church. Yet that is predicated upon a pre-existing unity in doctrine. Baptism has always required a unity of doctrine, and creeds themselves were initially devised precisely for use in baptism. Even in the cases where the ancient Church was re-establishing communion (either corporately or with individual believers), doctrine was always the initial gate through which those coming into communion had to pass. A common profession of faith has always been the prerequisite for engaging together in the spiritual life.

In any event, I did not ask “Who do they repent toward?” but rather what. Of course we may say that all should repent toward God. But if we do not have the same doctrine about Who God is and how He operates in this world, then our fundamental aims will be different and will not bring us closer together. Indeed, this is really why doctrine matters, because it is the “lab manual” for how one does the spiritual life. But if we are using different manuals, then we are engaging in the spiritual life differently. If we are not repenting in the same ways and with the same destination, then there is no unity that will result. You can’t pray and fast your way into unity if your prayer and fasting are not fundamentally of the same character and purpose.

To put it another way, because being an Orthodox Christian and being a Roman Catholic Christian have come to be different things, simply telling people that they ought to be the best Orthodox Christian or the best Roman Catholic that they can be will not overcome the schism. It will simply perpetuate it.

If we don’t start with the same dogma and doctrine, we will not be walking the same path, no matter how sincere or pious we may be. I’m not a Florovsky expert, but he in no way ever downplayed the importance of genuine theological dialogue (which he distinguishes here from “comparative religion” as a kind of academic pursuit). Indeed, he spent most of his life working precisely in such dialogue, having been at the formation of the WCC itself, and he kept working on it, even when it took a bad turn especially in the 1970s.

It’s not my intent to downplay theological dialogue either but rather not to minimize the ascetical life and if you undermine its value from the start or so tightly constrain it’s value to right doctrine again it seems to miss the point of orthodoxy itself which is right glory. It seems to me that seeking one would have an impact on the other and I’m not willing to dismiss it as mere pietistic hopefulness or simply suggesting that somehow magically it will create unity. If you make starting with the same doctrine and dogma the key then you are either hobbling yourself and others or implicitly communicating that any dialogue is meaningless. One may engage in dialogue but it isn’t perceived as sincere or rooted in something that is greater than the historical wounds and painful memories – which is why so few believe or trust that these meetings will have any lasting value or significance.

Does this mean you believe that those engaged in dialogue stop being Christians, that dialogue means they will stop praying and fasting? That’s the only conclusion I can come to based on your comments thus far. Why do you think that Florovsky is “dismissing” asceticism?

What?? Obviously I must be communicating poorly here because I have not been saying anything remotely along those lines. I haven’t been addressing Florovsky so much as responding to the flow of the comments. As the first commenter seemed to be saying there doesn’t seem to be anything new in what is being stated in the document and I have in no way said dialogue makes people unChristian or would lead to cessation of fasting or prayer. I believe that you were the one who stated that I was somehow suggesting that asceticism would magically produce unity. In any case, I was simply trying to make a point, perhaps again poorly, that theology and asceticism interpenetrate each other as does liturgical theology with the other two; that to develop a coherent and fruitful approach to dialogue one would need to see how they co-inhere. My comments were not intended to be a critique of Florovsky but an attempt to use what was said in the article above as a jumping off point for further discussion – to in some way respond to the call he speaks of and to think of what the response to that call might look like.

I don’t have an objection, really. I’m just a bit confused that he is (I guess?) reinforcing that Orthodox won’t be getting together with Catholics for “unity” based on already existing theological differences that circularly prevent the coming together. It’s like we are saying (and we are) “You guys have to admit you changed theology and chose your own way.” Who doesn’t know that the RCs did this except the RCs? Or if they do, they don’t want to recognize it for tribal, group, and hegemonic reasons. Again the problem.

I guess I was just curious as to why he spent a lot of time, energy, and eloquence stating that the Orthodox churches have maintained continuity since apostolic times without meaningful deviation, thus, “ecumenism” doesn’t exist — you gotta be Orthodox (small and/or big O).

Keep up the good work, Fr. Andrew.

As I see it (with one foot in the Tiber, and the other in the Neva–but not canonically anything yet), the only issue really left is primacy and infallibility:

1) Original sin–the West says it’s sin “only in an analogical sense”–from there it stands to reason that if it is a sin by analogy, and in reality is a state of the deprivation of original holiness, then there’s not actual tangible transfer of guilt in the Western view. Nathaniel McCallum has went very far on this blog to show the view of Carthage *is* the official Eastern stance on the issue. To take the official stance of Carthage via Trullo shouldn’t put one out of Eucharistic communion…

2) Immaculate conception–it seems based on Metropolitan Kallistos comments and others, that the principle theoretical objection to this is not so much about who the Theotokos is, but rather what original sin is. If we agree on original sin as articulated at Carthage, then the only thing left is articulating adjectives for Mary. Some Synaxaria explictly refer to ‘immaculately conceived’ and there is support from St. Photius the Great and St. Gregory Palamas. And immaculatly conceived doesn’t in itself *necessarily* imply that she was impeccable–I’m rather fond of St. Thomas Aquanis’s assertion that: “Therefore it seems better to say that by the sanctification in the womb, the Virgin was not freed from the fomes [the tinder for the fires of sin] in its essence, but that it remained fettered: not indeed by an act of her reason, as in holy men, since she had not the use of reason from the very first moment of her existence in her mother’s womb, for this was the singular privilege of Christ: but by reason of the abundant grace bestowed on her in her sanctification, and still more perfectly by Divine Providence preserving her sensitive soul, in a singular manner, from any inordinate movement.” Again, I don’t think following Photius and Palamas should put one out of Eucharistic communion…

3) Filioque–Rome has stated at Florence:

“Texts were produced from divine scriptures and many authorities of eastern and western holy doctors, some saying the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, others saying the procession is from the Father through the Son. All were aiming at the same meaning in different words. The Greeks asserted that when they claim that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, they do not intend to exclude the Son; but because it seemed to them that the Latins assert that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son as from two principles and two spirations, they refrained from saying that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. The Latins asserted that they say the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son not with the intention of excluding the Father from being the source and principle of all deity, that is of the Son and of the holy Spirit, nor to imply that the Son does not receive from the Father, because the holy Spirit proceeds from the Son, nor that they posit two principles or two spirations; but they assert that there is only one principle and a single spiration of the holy Spirit, as they have asserted hitherto.”

And at the Union of Brest:

“…that is, that the Holy Spirit proceeds, not from two sources and not by a double procession, but from one origin, from the Father through the Son.”

In summary, Rome is saying that the act of procession in its entirity must include a ‘procession FROM’ and a ‘procession TO’ in the one singular act of procession. The Father is the sole origin and source: the ‘procession FROM’. Christ participates in the singular principle of the total act of procession by being the ‘proceeding TO.’

Altogether differently we must consider whether it should be in the Creed. In a re-united Church, it is clear that–contra Humbert–that the East SHOULD NOT be forced to say the creed. As has been stated in the past, even if the East decided to want to include the filioque in Greek, there’s not a clear linguistic way to affirm what’s articulated above. “εκ Πατρός δι’Υιού” is as close as it comes. The ” καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ ” coupled with the “ek” in “ἐκπορευόμενον” on its face looks like ontological double procession, which Rome forcefully opposes as heretical.

Should the West drop it? Or should we all develop a *new* Creed? If a new Creed, does it just say “From the Father THROUGH the Son” or should it not speak of ontology, and only speak to oikonomia–like the Armenians? “…We believe also in the Holy Spirit, the uncreated and the perfect; who spoke through the Law and through the Prophets and through the Gospels;Who came down upon the Jordan, preached through the apostles and dwelled in the saints….”

Whatever is done, as long as no side adopts a heretical position, then it shouldn’t be an obstacle to Eucharistic communion.

4) Primacy–the 800 lb gorilla in the room.

5) Infallibility–well, we all agree that the first two papal encyclicals are infallible, right?

Fr. Andrew,

I would like to respond to your comment that “simply telling people that they ought to be the best Orthodox Christian or the best Roman Catholic that they can be will not overcome the schism. It will simply perpetuate it.”

I believe it is important not to hold this platform too strongly. Part of being a good Orthodox Christian or Roman Catholic is internalizing the will of Christ in your own life. The will of Christ includes the desire for unity among all the faithful.

Furthermore, to be a good Odx or RC one must learn humility. Humility is the key ingredient to good ecumenism (and I have seen both sides radically fail in this capacity for decades now).

I could go on. But essentially the reason why I disagree with your position, and I think it is a position that hurts ecumenical dialogue, is because when I look at Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy, I see a unity of theology, practice, and doctrine that is already extensive. Therefore, I think you ought rather to say that “Orthodox and Catholics, in order to overcome the schism, ought to be the best Orthodox and Catholics that they can…insofar as Orthodoxy and Catholicism already have a unity of belief and practice.”

I think this is also true of Protestants. Who are most often the Protestants who convert to Orthodoxy? They ones who were already serious about their faith and hungry for something more, that Protestantism couldn’t give them. These were Protestants who read their Bible, who prayed, who read church history and theology…they were trying to be the best Protestants that they could.

–Andrew

I agree with some of what you are saying here, but it seems to me that your critique of my remark is based on an interpretation of it that I don’t intend (and you saw that, too, I think). Someone who is the best Roman Catholic that he can be will believe in papal infallibility and supremacy, among other things. Those teachings are fundamentally incompatible with Orthodoxy. Likewise, someone who is being the ideal Protestant (of whatever stripe) is almost certainly going to believe that the Orthodox veneration of icons is in some sense idolatry or at least not permitted. He will certainly not believe that Orthodoxy is identical with Christ’s one Church. Again, both are incompatible with Orthodoxy. So you really have to stop being the best Roman Catholic or Protestant in order to become Orthodox.

So, what you are talking about (your “insofar,” etc.) is not what I was talking about. Mind you, I’m not in favor of that, either, because it’s essentially just a sort of lowest common denominator form of Christianity, i.e., don’t do the stuff that the other side rejects. But that’s not really being true to your tradition. It’s essentially a form of Protestantism, which feels free to reject some parts of tradition while embracing others.

Conversion requires a genuine change — you must begin to believe something you did not before or begin to reject something you once believed. It’s not merely sticking to being the best thing that you were before. It’s becoming something else. There’s no way around that.

We are all being converted, all the time, into something else.

In a sense, yes, but if you mean that we should always be changing our doctrine and our ecclesial loyalties (which is what we were discussing), well, no.

My whole point has been that the model of converting must go beyond doctrine and ecclesial loyalties. This is where I agree with Father David above. Ascesis, Love, and Perserverance are all aspects of that conversion which overlap among Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants. This is especially true for Catholics and Orthodox, who share many basic principles of moral and (s-called) mystical theology.

(By the way, I feel very awkward and strange speaking to a Priest about this, albeit over the internet. I hope you take none of this personally, or as impudence.) But I must point this out: surely you have noticed that the least successful conversions to Orthodoxy are always the ones who are gung-ho about doctrine and ecclesial loyalties (“St. Francis was demon-possessed! Take back Constantinople!”) without a healthy dose of humility, receptivity, and magnanimity.

Here is a better way of framing the question: Who would you rather be engaging in the global ecumenical dialogue? The best Orthodox and Roman Catholics, or the worst ones? For my part, I am glad that there are Orthodox ecumenists like Met. John Zizioulas and Met. Hilarion Alfeyev, and Catholic ones like Msgr. Paul McPartlan. The holiness of these men is what gives me hope, along with their commitment to the dogmas of their respective churches. Yes, even Msgr. McPartlan (and others’) commitment to the so-called “Western Heresies.” I do not think I would trust ecumenical dialogue with a Catholic who did not hold to Catholic dogmas.

Under your model, what sort of ecumenism can there be?

To answer that, I suppose you could just link me to [https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2013/03/22/should-i-want-everyone-to-become-orthodox/], but you should know that I’ve read your various arguments before and could never figure out how you reconcile some of the views about Truth which you present in your article “Una Sancta” with what seems to be your general perspective on ecumenism in “Should I Want Everyone to Become Orthodox?” What’s wrong with saying that seemingly opposing, infallible dogmas of East and West are incomplete understandings of Truth, which can ultimately be reconciled by more complete understandings?

An example of what this can look like (though not specifically East/West) would be the Lutheran-Catholic “Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification.”

What’s wrong with saying that seemingly opposing, infallible dogmas of East and West are incomplete understandings of Truth, which can ultimately be reconciled by more complete understandings?

What’s wrong with that is that both Orthodox and Roman Catholic fathers in the faith — saints, even — have looked at those exact questions and determined that there really were mutually incompatible beliefs in play.

Or, to put it another way, why should I think myself smarter or holier than Ss. Photios the Great, Gregory Palamas and Mark of Ephesus? They knew heresy when they saw it, and the Church has agreed with them.

I don’t regard ecumenism that papers over differences to be of any use at all. The only sort that has any real worth to it is the sort that is based on authentic unity of doctrine. Anything else is a disservice to everyone involved. Yes, one can find truth everywhere, no matter its brand or label, but either Orthodoxy has the fullness of truth or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, and especially if no communion has it, I’m not really sure what the point of being a Christian really is. If there’s no real path to get where we need to go, then why keep walking?

I stopped being a good, faithful Protestant in order to become Orthodox. So, your observation is very correct, Father Andrew. It is very sensical.

Fr. Andrew,

Please give some citations to support the claims about the Fathers you mention in the first two paragraphs, then we can analyze them together using a critical methodology. I have read some of these types of arguments about the words of Sts. Mark and Photios in the articles by the so-called “Orthodox Christian Information Center”…and I have also read the much more balanced and insightful refutations.

It really saddens me that a lot of Orthodox bloggers tend to see Ecumenism as either “papering over differences” or “converting each other.” In your words…”Either Orthodoxy has the fullness of truth or it doesn’t.”

Truth is a Person, Father. You most of all should know this.

–AC

Photios’s Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit, Gregory’s Triads and pretty much anything you’ll find quoted from Mark show this pretty easily (especially as those things were received conciliarly). If you’re not familiar with those works, well, I’m not sure what to tell you.

I didn’t put forward any definition of ecumenism, BTW, and I certainly didn’t define it as “converting each other.” I am more interested in Florovsky’s “ecumenism in time,” whose ultimate purpose was gradually to bring non-Orthodox bodies (back) into alignment with Orthodoxy. He was exceptionally active in the ecumenical movement but never compromised Orthodoxy nor set aside real differences. His macro-level approach didn’t prevent him from receiving individual converts, though.

Truth is indeed a Person, and that’s why I can’t accept the dismembered Christ Whom you seem to be promoting.

As an addendum:

Here are some quotes from Mark of Ephesus and here are some more that talk about what I mean. One won’t find in here the idea that Orthodoxy and Rome just each have incomplete pieces of the truth that they have to somehow stick together to get the real deal.

Andrew,

Your words are quite simply, heresy.

The Church of Christ is one, The Orthodox church. She is pure and chaste and keeps her couch undefiled from the ravings of heretics and schismatics. Any dialogue resulting in inter-prayer movements with heretics and schismatics (Trampling upon the canons and creating participants in heresy) is an act of human folly at best and satanic delusion at worst, and most likely a combination of the two. This is not even an extreme personal opinion, this is the authentic teaching of the church as expressed by the fathers and the canons which the ecumenists are wont to spit upon whenever they get the chance.

Why do you suppose the whole of Mt. Athos ceased to commemorate The Patriarch of sorry memory, Athenagoras in the divine liturgy? Because of his neo-papal patriarchal heresies. And this was their right in accordance with the 15th canon of the 1 and 2nd synod held under St. Photios the great.

Ecumenism is a betrayal of the constant dogmatic teaching on the church, with its embracing of the branch theory, the two lungs theory and “baptismal theology.”

Let’s be very clear: The Orthodox church does not recognize any grace in any “sacraments” outside her own body. Protestants, Catholics and Schismatics and heretics in general simply pour water on one another with zero effect. The limits of the church is communion with the Orthodox. Outside of this communion, one cannot have the indwelling of the holy spirit, because there is no sacrament which will call down the spirit. I disagree with the “conservative” sacramental “agnostics” because they simply ignore the canons. Which canons?

For example:

Apostolic Canon XLV Ratified by Trullo and the 4th and 7th ecumenical councils.

THE BEGINNING OF CANON 2 OF THE COUNCIL “IN TRULLO”: Declaring the Apostolic Canons to be a part of Orthodox canon law.

“It has also seemed good to this holy Council, that the eighty-five canons, received and ratified by the holy and blessed Fathers before us, and also handed down to us in the name of the holy and glorious Apostles, should from this time forth remain firm and unshaken for the cure of souls and the healing of disorders. And in these canons we are bidden to receive the Constitutions of the Holy Apostles [written] by Clement. But formerly through the agency of those who erred from the faith certain adulterous matter was introduced, clean contrary to piety, for the polluting of the Church, which obscures the elegance and beauty of the divine decrees in their present form. We therefore reject these Constitutions so as the better to make sure of the edification and security of the most Christian flock; by no means admitting the offspring of heretical error, and cleaving to the pure and perfect doctrine of the Apostles.”

“Let a bishop, presbyter, or deacon, who has only prayed with heretics, be excommunicated: but if he has permitted them to perform any clerical office, let him be deposed.”

Canon LXIV.

If any clergyman or layman shall enter into a synagogue of Jews or heretics to pray, let the former be deposed and let the latter be excommunicated.

This goes for any hierarch who has prayed with the Latins and celebrated liturgical services with them. Do I REALLY have to name them?

Canon XLVI.

“We ordain that a bishop, or presbyter, who has admitted the baptism or sacrifice of heretics, be deposed. For what concord hath Christ with Belial, or what part hath a believer with an infidel?”

Canon LXVIII.

If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon, shall receive from anyone a second ordination, let both the ordained and the ordainer be deposed; unless indeed it be proved that he had his ordination from heretics; for those who have been baptized or ordained by such persons cannot be either of the faithful or of the clergy.

So when the Patriarch of Alexandria recently recognized Coptic baptisms as valid? His clergy ought to cease commemorating him at the Liturgy AFTER this has been brought to his attention.

You want to hear what faithful Orthodox are demanding from their Hierarchs?

Conclusions of the Inter-Orthodox Theological Conference

“Ecumenism: Origins — Expectations — Disenchantment”

” Proposals…

8. That it be made manifest to church leaders everywhere that, in the event that they continue to participate in, and lend support to, the pan-heresy of Ecumenism—both inter-christian and inter-religious—the obligatory salvific, canonical and patristic course for the faithful, clergy and laity, is excommunication: in other words, ceasing to commemorate bishops, who are co-responsible for, and co-communicants with, heresy and delusion. This is not a recourse to schism but rather to a God-pleasing confession, just as the ancient Fathers, and bishop-confessors in our own day have done, such as the esteemed and respected former Metropolitan of Florina, Augustinos, and the Fathers of the Holy Mountain (Athos).

9. It be declared with the sound of the trumpet that Ecumenism and unconditional dialogue with heterodox and non-Christians are not beneficial, but injurious, and thus not the work of love, but merely of a worldly way of thinking; these are conventional relationships, which aim not at spiritual ends but self-serving interests. They wear down and taint the Orthodox phronema through intermingling and obfuscation, and as a result bring harm to the faithful, since without purity of dogma, even in lesser matters, no one can be saved. To non-Christians and to the heterodox they close the gate of salvation, obstructing the former’s view of Christ as being the only path of salvation, and hindering the latter from seeing the Orthodox Church as the ark of salvation, as the only Church. God, in His infinite love for mankind and the world, desires the salvation of every man. On the contrary, the Devil, who is the enemy of salvation, wars against man in a diversity of ways out of envy and hatred

Consequently, out of love we reject Ecumenism, for we wish to offer to the heterodox and to non-Christians that which the Lord has so richly granted to all of us within His Holy Orthodox Church: namely, the possibility of becoming and of being members of His Body.”

These are not even Old Calendarists! These are ORTHODOX Christians demanding accountability from their hierarchs who are basically playing with heresy. And they give full justification to the moderate Old Calendarist groups such as the Holy Synod in Resistance (Those who do not deny those in “World” Orthodoxy posses grace…for now.)

So, please, let us all awake and actually be conversant with our fathers and the canons, and For Christ’s sake (literally) Have some Zeal!

The sinner and profligate,

Isaac

Dear Fr. Andrew and Isaac,

Thank you for your opinions. This topic is obviously quite large, and pithy blog responses won’t quite do it justice.

As an aside, Isaac, I don’t think you should call Patriarch Athenagoras “of sorry memory.” Regardless of your opinions about ecumenism, it does your soul no good to say things like that.

I can recommend a few books on the subjects that we are discussing here, or at least just list some names whose more up-to-date works may interest you: Adam A. J. DeVille, Paul McPartlan, David Bentley Hart, Laurent Cleenewerck, Met. John Zizioulas, Met. Kallistos Ware, and Robert Taft. I’m sure none of their work is new to you, as you both seem very well-read. But they may be of use to other readers.

The long and short is that the question of ecumenical ecclesiology is not the sort of thing that can be “resolved” with short quotes from fathers or councils without a full critical engagement. And naturally, there are always going to be two (or more) schools of thought. Whole departments and institutes are committed to answering these questions. I would challenge both of you to think more openly about this topic, and about the best way of presenting the Gospel of Christ to the world.

And Isaac, please be careful with your use of the word “heresy” and your other uncharitable statements. Please think about how our Lord would enter these kinds of conversations.

–Andrew

I’m having a hard time seeing how “ecumenical ecclesiology” isn’t essentially just teaching the “branch theory.” How is your call to “think more openly” anything other than essentially that? Is Christ divided? It seems that, for the vision you’re teaching, the answer is a pretty emphatic “yes.”

This is really just a basic denial of traditional ecclesiology and even traditional understandings of both heresy and schism. I’m still interested in the answer to my question from earlier: If the Holy Fathers regarded certain things as being heretical and then were confirmed in their views by conciliar decree, why should we now decide that we know better than they?

Hello Father,

If you are confused about Branch Theory and Ecumenism, I would recommend you take a thorough look at the Wikipedia articles entitled “Branch Theory” and “Ecumenism.” They lay out the basic premise very clearly, and it may clarify your thinking on this subject.

The difference between ecumenical ecclesiology and the branch theory is epistemological. Those who hold the branch theory claim that they have a concrete knowledge of the church’s instantiation, and it is instantiated in three places: Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Catholicism.

An ecumenical ecclesiology merely allows for the possibility that what constitutes the Church isn’t always clear-cut. Unlike a vision of the Orthodox Church which supposes that only “Orthodox” Bishops and their flocks constitute the Church, it allows for the possibility that the body of Christ extends beyond such a rigid propositional structure. This is the only way, for example, to account for the fact that “Orthodox” Bishops sometimes slip in and out of communion with each other and with various Patriarchs, or on a more historical level, to account for the fact that when Rome and Constantinople were separated in 1054, both were somehow still in communion with the see of Antioch.

The answer to your question from earlier is simply that times change. The “fullness of Truth” possessed by the Orthodox Church cannot be reduced to propositional statements made by one father or other, or even by this or that Council, in its historical context. All must be understood in context, and especially in the context of the Church’s role in history. This obviously sounds like a cop-out, but only because to answer this question in completeness would require a book-length response (and such books do exist, and can be found even among some of the authors I mentioned earlier). To deny the need for interpreting the ideas of the councils for particular situations, and to simply cite things that Orthodoxy has held at various points throughout history, is to behave just like a Sola Scriptura Protestant. The problem is that you make the text a thing-unto-itself, forgetting the existence of the text-reader dialogue, and especially the Community-as-Text (without which, neither Bible nor Canons would exist).

I’m not confused, actually, but it seems to me that you might be. I mean no offense, but you’re basically just preaching the branch theory in other language.

It seems to me that your ecclesiology misses the rather significant point that the Church isn’t merely a matter of interpreting texts, but of communion. This isn’t just about canonical boundaries, either, but of the ontology of communion in Christ. What you are positing is truly a divided Christ: a denominationalist theory in which multiple groups—all claiming to be the Church yet not in communion and whose fathers in the faith all recognized each other as heretical—each have a piece of the truth and do not truly have the fullness of Christ present within them.

One can try to reinterpret texts all one likes, but there’s only so far one can really go with that. When (for instance) St. Mark of Ephesus called the Filioque a heresy and was confirmed in that by conciliar decree, there’s really not much wiggle room. Dogma is dogma. Everything is not actually up for grabs.

“Ecumenical ecclesiology” is an oxymoron, because it presumes precisely that there really is no such thing as the Church.

Come now! These criticisms are not logical.

“The church is about communion”: yes, I agree. That’s what I am talking about as well; ontological boundaries.

It seems that you are thinking of diverse Christian ecclesial bodies as “multiple groups” in a sense that makes them…ontologically distinct from one another? That seems philosophically short-sighted, even if you were to posit that Catholics and Coptics don’t have valid sacraments. How would that look, exactly? When did these seemingly valid sacraments become invalid? And don’t simply point to licitness–we are all aware that sacraments are performed illicitly, even within Orthodoxy, all the time.

If we are sharing the same Eucharist (setting aside questions of diversity and its ontological effects), then we do not have “a piece of the Truth”. And even if you look for the reflection of Truth’s fullness in the truths found in Church Dogma, I would venture that the future of Oriental-Eastern Orthodox ecumenism, or Catholic-Orthodox ecumenism, is not to be found in “give up your (Western, Non-Chalcedonian, etc.) heresies and then we will let you back in.” There are more complex ways in which these Dogmas can be reunderstood, or canonically reduced to theologoumena so that they can be analyzed in union with Oriental or Western Perspectives.

Of course, one could take your side, and posit “St. Mark called the filioque a heresy” and that’s that. But even a hardliner like yourself would understand that there are several different schools of thought in the West as regards the meaning of the filioque, and also the fact that the Latin church does not consider the Creed to be deficient without its use (a.k.a., they can drop it, as the Eastern Rite Catholics do, or as Pope Benedict XVI (for example) did when engaged in ecumenical prayer). To mindlessly repeat that we will never be reunited with the Catholics, because they Catholics believe that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son as well…well, Father, your ideas would have been very much at home in the 15th century. But Glory be to God, the 15th century did not mark the end of advancement in Orthodox thought, and we are slowly starting to move past these divisions.

There is much to nuance in all of these theological debates. I do have a question I would like to ask you, Father, because I feel that you will give me a much more reasonable response than others who like to rant about the “Pan-Heresy of Ecumenism.” What do you feel is gained by your vocal promotion of the ecclesiology to which you subscribe? Is it that you truly feel there is nothing to be gained from the West’s theological perspective? Or do you fear that the Orthodox faith will be corrupted?

I am concerned with this question, because when I speak on this ecclesiology (which I feel is the more accurate), I do so because it shines the light of hope onto a dark situation. I am not saying “I know all the answers, and I know that the Orthodox Church needs some of these answers which have been preserved in the West and not in the East.” I’m only saying that if there is a Western perspective on Truth which can shed some better light on it, then the East would do well to investigate and possible incorporate that perspective (with the added benefit of two ecclesial bodies achieving a more concrete and visible unity).

I suspect that you are misunderstanding me, perhaps deliberately. The problem with your approach, it seems to me, is that you allow only for a binary set of views here, where on the one hand we have “ranters” and on the other we have the branch theory of ecclesiology or some denominationalist form of it where no church is really the Church wherein the fullness of the Truth Himself dwells.

Yet it is possible to believe that there is nothing at all lacking in the Orthodox Church and nevertheless believe that there is something valuable to be gained from engaging with western forms of theological expression. This isn’t “hardline.” It’s just believing in One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.

In any event, nothing written here has been “mindless repetition.” It is not mindless to follow the Holy Fathers rather than stand in judgment of them.

Unfortunately, western rationalism has had its influence on certain Eastern Orthodox leaders, who are members of the Eastern Orthodox Church only in body. In spirit, they really belong to the West, which they consider to “reign” over the secular world. But if they were to view the West spiritually, to see it in the light of the East, in the light of Christ, then, they would be able to discern its spiritual twilight. For the light of the intelligible Sun, the light of Christ Himself is disappearing from the West and a deep darkness is slowly setting in. All these gatherings and conferences are the work of the evil one; the leaders are engaging in endless discussions on issues that need no discussion, issues that even the Holy Fathers never addressed in the past. All these are meant to confuse and scandalize the faithful and drive some of them to heresies and others to schisms, so that he can gain more ground. Ah! The misery and confusion they bring to people! (p. 227)

When holy Martyrs did not know how to explain the doctrines of the Church, they would often say, “What I to believe is what the Holy Fathers have taught.” That was enough to lead them to martyrdom. You see, they could not defend their faith with arguments and persuade those that persecuted them, but they trusted the Holy Fathers. He would reason to himself, “How can I not trust the Holy Fathers? They were far more experienced and virtuous and holy than we are. How can I accept this nonsense and not protest when people insult the Holy Fathers?” We must trust Holy Tradition. The problem today is that so many embrace European courtesy and try to appear nice. They want to be viewed as open-minded and tolerant and end up bowing to the two-horned devil. “We don’t need many religions,” they say, “one, universal religion will do.” This way they want to level everything. Some of my visitors actually think this way. “Those of us who believe in Christ should form one religion,” they once told me. “What you are suggesting,” I replied, “is that we take eighteen carat gold that has been purified and separated from copper and mix it with copper again. Does this make any sense? Ask a jeweler, ‘Does it make sense to mix base metals with gold?’ So many have struggled to keep our Orthodox dogma pure and make it shine.” The Holy Fathers were right to forbid relations with heretics. But today people don’t see that, “We should pray together with the heretic, the Buddhist, the fire-worshipper, even the demon-worshipper,” they say. “The Orthodox should participate in joint conferences and prayer sessions. It’s important that we are present.” What kind of presence are they talking about? They try to approach everything with logic and end up justifying the unjustifiable. If we follow the European spirit, we’ll end up putting spiritual matters under a Common Market.

A few among the Orthodox, who are rather superficial individuals, seeking self-promotion in a self-appointed ‘mission”, organize conferences with the heterodox to create a stir. They are supposedly promoting Orthodoxy, but all they do is bring in the heterodox and make a “mixed salad”. This gets the super-zealots angry and they go to the other extreme; they blaspheme against the Mysteries of the New Calendar Orthodox, and so on and thoroughly scandalize souls who are full of devotion and Orthodox sensitivity. The heterodox on the other hand, come to these conferences, behave as if we all have to learn from them, and then take whatever good spiritual material they find in Orthodoxy, process it in their lab, add their own colour and label and present it as an original idea. And there are all kinds of strange people who are moved by such ventures, and end up spiritually damaged. The time will come, however, when the Lord will bring forth great figures like Saint Mark the Eugenikos and Saint Gregory Palamas. They will gather together all our scandalized brothers and sisters, to confess the Orthodox faith and secure the Orthodox Tradition, bringing great joy to the Mother Church. (pp. 382-384)

—Elder Paisios the Athonite, from With Pain and Love for Contemporary Man

Beautiful. Holy father Paisios, pray to God for us!

Andrew,

May God save us all, especially me, the prideful and arrogant one.

You said:

“An ecumenical ecclesiology merely allows for the possibility that what constitutes the Church isn’t always clear-cut.”

This is a heretical view. I am not throwing around terms, it is simply a matter of historical fact. It does your soul no good to second guess the teaching of the fathers in light of “modernity.” Modernism is an ecclesiological heresy, as is every variation and type of the branch theory whether it be the “Two Lung theory,” “Baptismal theology,” the “Invisible Church” or any host of deluded and ravings of the followers of Antichrist.

Come now, love is eminently practical. We see you as deviating from the faith once handed down into the byways of heresy and delusion. You have abandoned the fathers, you have written them off as needing a greater context than the errors they were condemning, and you have abandoned the heart of their message. Love demands that we call you back and shout:

“My friend, your salt has lost its savor.”

All the fathers can be summarized in a single understanding: The soul of man is sick from his youth and is need of a cure. That cure is the therapeutic process of carthasis, theoria and theosis, or purification, illumination and deification. This is in order that man can be remade into the image of God. This process can only be accomplished within the confines of the Orthodox church, and those confines are delimited by the fathers in their condemnation of heretics, schismatics and conventiclers. Dogma itself is a corrective aimed at the restoration of spiritual integrity. It is not an abstract intellectual exercise, and heresy is not simply a negation of an intellectual truth. Heresy is prideful self-will and darkness which arises from a soul that believes it knows better than all. This leads it to exalt its opinions above the fathers and commit an act of idolatry, in worshipping a false notion of God.

The cure for this begins with repentance, is officially initiated with Baptism, Chrismation and the Eucharist, and is maintained with the Eucharist and confession. This cure has no existence outside of Orthodoxy. The Holy Spirit is not given outside the Church. That does not mean he is not ACTIVE, or else none would convert, but as St. Diadokos of Photiki says:

“Before holy Baptism, grace encourages the soul from the outside, while Satan lurks in its depths, trying to block all the noetic faculty’s ways of approaching the Divine. But from the moment that we are reborn through Baptism, the demon is outside, grace is within. Thus whereas before Baptism error ruled the soul, after Baptism truth rules it. Nevertheless, even after Baptism Satan (can) still act upon the soul….”

Grace does not indwell us before baptism, but it can inspire.

Again, St. Hilarion Troitsky, the Hieromarty says,

“Outside the Church it is impossible to preserve love, because it is impossible to receive the Holy Spirit.”

St. Theophan the recluse himself says, “There is no other path… Without the Sacrament of Chrismation, just as earlier without the laying on of hands of the Apostles, the Holy Spirit has never descended and never will descend.”

The cure for the illness of man’s soul is Orthodoxy. There is no other cure because anything else is either an admixture of poison, or a subtraction of active ingredients.

So please understand: You are walking a path that is heretical and will lead to delusion. The signs of this blossoming delusion are a discrediting of the fathers and a love of the spirit of the times .

Your salt has no savor.

This doesn’t have anything soever to do with being “nice.” Niceness is for those who have lost their footing and need to be pampered in every random decision they make because their conscience convicts them. This is about charity. Charity demands that I tell you: “There is a cliff up ahead, and you are running at it full speed! Know what happens when you run off a cliff? You die!”

Please don’t die!

Forgive me, Per your quotes as stated above, in the Council of Trullo; Then The EOC are themselves in Heresy, you should not participate any catholic events, have no communication, etc.. !

I honestly think it is time for a great and Holy Council. THE EOC, will have to eliminate there own heresies, bring themselves back to Christ, to the one True church.

Yes it is beginning with baptism, The EOC accepts Baptism by The so Called Heretics of The RCC. logically speaking, the EOC, you should really have nothing to do with RCC period.

Im sorry, I did not mean to be rash. Please forgive me. One Thing I do believe, both churches will reunite, I believe it is possible, through humility, humbleness, Love, and most of all HOPE. we must never give up HOPE.

I think many have forgotten that word.