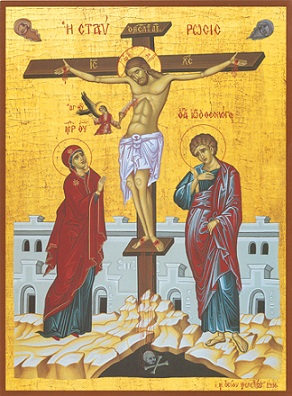

One verse cited often with regard to the crucifixion of Christ in the Orthodox liturgical tradition is Colossians 2:14. “When he canceled the handwriting in the decrees against us, which were opposed to us. And he has taken it from our midst, by nailing it to the cross.” This verse describes how, as the previous verse says, we who were dead in our transgressions were made alive by having those transgressions taken away. The language used here offers us yet another window through the scriptures to understand the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ for our sakes upon the cross. Though it may not be apparent in English translation, this language of the handwriting of a decree is part and parcel of one set of the thematic language used throughout the scriptures to describe human sin and its relationship to death.

One verse cited often with regard to the crucifixion of Christ in the Orthodox liturgical tradition is Colossians 2:14. “When he canceled the handwriting in the decrees against us, which were opposed to us. And he has taken it from our midst, by nailing it to the cross.” This verse describes how, as the previous verse says, we who were dead in our transgressions were made alive by having those transgressions taken away. The language used here offers us yet another window through the scriptures to understand the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ for our sakes upon the cross. Though it may not be apparent in English translation, this language of the handwriting of a decree is part and parcel of one set of the thematic language used throughout the scriptures to describe human sin and its relationship to death.

The Greek word translated typically in this verse as “handwriting” is translated so based on a woodenly literal rendering of a Greek compound word made up of the word for “hand” and the word for something written. Its most common usage, however, in the first century AD was to refer to an IOU or a promissory note. Its attachment here to the word translated “decree” which refers to an official public document moves the meaning toward the latter usage, a promissory note or a public document describing a debt owed. St. Paul is therefore here describing the effects of our transgressions, our sins, as an accumulated debt which represents a claim against us. Christ, through his atoning sacrifice on the cross, cancels this debt. The certificate of that debt is nailed to the cross and torn asunder.

The imagery of transgression as debt here utilized by St. Paul is commonplace in the Gospels. Depending upon the Gospel which one is reading, the Lord’s Prayer asks either for the forgiveness of debts or of trespasses. St. Matthew’s Gospel gives the Lord’s Prayer as referring to the forgiveness of our debts as we forgive our debtors (Matt 6:9-13). Immediately thereafter, however, as an interpretation of the prayer, Christ says that if we forgive the trespasses of others, then our trespasses will be forgiven us (v. 14-15). St. Luke, however, phrases the Lord’s Prayer as referring to the forgiveness of our sins as we forgive our debtors (Lk 11:4). These concepts are so closely aligned in Second Temple Jewish thought that they can literally be used interchangeably. In describing the forgiveness of sins, Christ uses debt in several of his parables (eg. Matt 18:23-35; Luke 7:36-47).

This understanding of sin as a debt, however, goes well beyond merely an analogy to help us understand forgiveness. Though not so in most of the cultures of our day, in the ancient world, the concept of debt was closely tied to the institution of slavery. Slavery in the ancient world was not primarily an instrument of racial or ethnic oppression. Rather, it was primarily an economic institution. With no concept of “bankruptcy” in the modern sense, the means by which a debt which could not be paid would be settled was indentured servitude. A person would work off the debt by becoming a slave. As the head of a household, not only a man who had incurred a debt would be sold as a slave, but his entire family. Children born into the family would be considered to be subject to the debt incurred by the father and might live their whole life in slavery attempting to pay it back or otherwise earn freedman status. Until that point, their lives and actions were not their own but were under the control of the person who held their certificate of debt and so had a claim to ownership of them.

In his Epistle to the Romans, St. Paul uses this language of debt and slavery to describe the relationship between sin and death (6:16-23). St. Paul posits that the wage of sin is death. Death is the means by which the debt incurred through sin is paid and so death, through the slavery of sin, projects itself back through the life of the debtor, expressing itself in the form of continued sin, which in turn increases debt and further enslaves in a vicious cycle (Rom 7:7-24). Because this debt has been owed by every human person who has ever lived, each person dies for their own sin (Deut 24:16; Jer 31:30; Ezek 18:20). Further, the devil is connected to this imagery as the holder of the debt. After his rebellion in Paradise, the devil was cast down to the underworld and given, for a time, dominion over the dead. Through death and sin, he has been able to enslave the great mass of humankind, with this certificate of debt as his claim over everyone who sins.

A critical theme of St. John’s Gospel is that Christ, as sinless, does not owe any debt to death. In fact, it was impossible for Jesus to be killed. Rather, he chooses to lay down his life and having done so voluntarily, is able to take it up again (John 10:17-18). Because Christ is without sin, the devil has no claim over him whatsoever (John 14:30-31). He cannot even lay claim to his body through decay (Jude 9; Acts 2:27). Because he had no sins of his own he was able to die for ours (1 Cor 15:3). Because his life is the ineffable, infinite life of God himself, it is able to pay the debt owed to death for every human person setting them free from bondage to sin, death, and the devil. The devil is thus rendered powerless and deprived of even his kingdom of dust and ashes. “Since, then, the children have shared in blood and flesh, he himself, in the same way, shared in the same things, in order that through this death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is the devil, and might set free those who, through fear of death, were subject to a lifetime of slavery” (Heb 2:14-15).

This language of manumission and redemption, of being freed from slavery through Christ’s sacrifice, is also entailed by the paschal language surrounding Christ and his death. Christ died not on the Day of Atonement, but the Passover. The celebration of Pascha was and remains for Jewish communities a celebration of freedom from slavery. Slavery to a spiritual tyrant who wielded the power of death. St. Peter can, therefore, speak of us having been purchased by the blood of Christ, the paschal lamb (Matt 20:28; Mark 10;45; 1 Pet 1:18-19). St. Paul can say that Christ has been sacrificed for us as our Passover (1 Cor 5:7). St. John the Forerunner’s primary witness to Jesus Christ is that he is the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world (John 1:29). It is the lamb who was slain whom St. John sees seated upon the heavenly throne (Rev 5:6).

Redemption in this sense, from the power of death and the devil, is universal. On the last day, all will be raised from the dead, not only the righteous (John 5:25-27; Acts 24:15; 1 Cor 15:52; 1 Thess 4:16). Death has been destroyed in Christ’s victory over it. St. Paul can say that Christ is the savior of all men, especially those who believe (1 Tim 4:10). The power (kratos) of death which the devil wielded has been taken away from him so that now all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to Christ Pantokrator (all-powerful; Matt 28:18; Eph 1:21; Jude 25). Every human person now belongs to Christ as their Lord and Master (1 Cor 6:19-20). Christ now rules over all of creation, over those who accept and embrace him as Lord and Master of their life and over those who continue in rebellion against him (1 Cor 15:24-26). In the end, every knee will bow and every tongue will confess that Jesus Christ is Lord (Rom 14:11; Phil 2:10-11).

The heresy of universalism which has arisen from time to time in the history of the church comes from a misunderstanding of this universal element of redemption. What is said about the resurrection of the dead and Christ’s dominion is then taken to also be speaking of entrance into the kingdom and eternal life. The scriptures, however, are utterly clear that the resurrection of every human person who has ever lived is a precursor to Christ’s judgment of the living and the dead. “Do not wonder at this, for the hour comes when all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out; those who have done good to the resurrection of life and those who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment” (John 5:28-29). Rather than removing judgment from all of humanity as they suppose, Christ’s victory over death makes him the sole judge of all of humanity (John 5:22; Rom 14:4). No one but Christ exercises judgment over human persons, including the devil and his demons. They no longer have any claim. Christ is the Lord and so the judge of all.

The gospel of Jesus Christ is the story of his great victory over the powers of sin and death and the devil culminating with his enthronement at the right hand of the Father with dominion over all the earth. This is a proclamation which brings joy and freedom in our being set free and receiving forgiveness of our debts. But it concludes with the warning that this same Jesus will appear to judge the living and the dead. It is this final proclamation which has always produced the question, “What must I do to be saved?” It is this final proclamation which has brought us all to live lives of repentance and faithfulness within the community of the church.

Hey Fr.

Great article. Would it safe to say that what St. Paul says about our record of debt isn’t that Jesus paid the debt but that he cancels it? Is that splitting hairs or an important distinction?

Both sets of language are used, both the language of cancellation of debt and the language of purchase or ransom. The emphasis in both cases, however, is not on some mechanic, but rather on the freedom from slavery to sin and death in order to serve Christ.

Interesting article! In terms of spiritual life, I always thought of trespassing as crossing the line and now one is in a state of sin. Then the debt of sin has to be paid – yes. So, would you say there is good meaning in both “trespassing” and “debt?”

God bless…..

Excellent Father. Thank you.

Your elaboration on the meaning of sin and death in light of slavery as the early Christians knew it shed a much needed light that I didn’t even know I needed!

Throughout the article I have formed several questions. Some may not be pertinent to this post but your answers would help me form a clearer picture of the topics you attend to and help form a more unified message of the Old and NT.

1) “For when you were slaves of sin, you were free in regard to righteousness ” . Rm 6:20. What is St Paul saying here?

2) You say ” Children born into the family would be considered to be subject to the debt incurred by the father and might live their whole life in slavery attempting to pay it back or otherwise earn freedman status.”

In regards to being indebted slaves and its vicious cycle, could St Paul have been drawing from verses such as this? :

‘The LORD is slow to anger and abundant in lovingkindness, forgiving iniquity and transgression; but He will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generations .’

Num 14:18

And why does Ezekiel seem to be saying the opposite of the above verse regarding the guilt of future generations? :

“The person who sins will die The son will not bear the punishment for the father’s iniquity, nor will the father bear the punishment for the son’s iniquity; the righteousness of the righteous will be upon himself, and the wickedness of the wicked will be upon himself.” Ez 18:20

3) In the post you linked, “Who is the Devil?” you say:

“Sheol literally means ‘the grave’, but was the word across early Semitic languages for the underworld, the realm of the dead.”

Did the ancients believe that “the dead”( in Sheol) have consciousness? When they speak of the “underworld”, it seems there is not only consciousness, but bodily form. My line of thought is that they understood death not as annihilation, but existence apart from our created purpose, that is, unity with God and all creation. Later St Paul uses the analogy of “slaves to sin” and its debt as death. Also, I have in mind where Christ said three times (Mk 9:44-48) “Where their worm (consciousness?) dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.” And, as well, it is known as the kingdom of Satan (thus a consciousness of it), even though it is described as “dust and ashes”. Further, in this life we are alive, but can be dead in sin, if not repentant and graced with the sacrament of Baptism (reality manifest through sacramental ritual).

4) “…God himself, it is able to pay the debt owed to death … not owed to The Father. Ok. Then, this is not the same as saying Christ paid a debt to Satan , but paid a debt for us , correct? He freed us from “Slavery to a spiritual tyrant who wielded the power of death. ”

5) “In the end, every knee will bow and every tongue will confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.”

I understand what you say about Universalism. The Church clearly has spoken against this teaching. Still, there are those who hope and pray that “none should perish”. I pray that every knee will bow in worship, knowing as well the dangers of a “seared conscience”. Also knowing full well that God will judge rightly at the Dread Judgment. Do you have any reservations with this type of prayer, Father?

Again, many thanks, Father Stephen.

1) St. Paul in that passage is saying that when they were slaves to sin, righteousness made no demands of them. But now that they are freed from the power of sin, they aren’t just free to do whatever they want. Rather, now they must serve righteousness, I.e. Christ. Christ has purchased them, they belong to him, and he will judge them on the last day.

2) The Ezekiel passage is in the context of the state of things in the new covenant which was later inaugurated by Christ. Before, from Adam on, human persons were born enslaved to sin. Now, every person is answerable to Christ for the works he or she has done in this life.

3) This is a tricky question, because ‘consciousness’ isn’t really an ancient category. Those in Sheol or Hades are described as shadows of their former selves or as memories. In the ancient world, existence meant existing in a web of meaning and purpose. Life meant living in a series of communal relationships. So those in Sheol weren’t seen as living or existing in the proper sense. At the same time, there are stories of the. Communicating with the living. Use of language implies at least something that we would call consciousness.

4) Right. Both the language of debt cancellation and the language of ransom or purchase are used, but in both cases, the emphasis is not on a mechanism, but on our freedom from slavery to sin and death in order to serve Christ. The ransom language is also used regarding the deliverance of Israel from Pharaoh, though Pharaoh received no payment other than a crushing defeat.

5) As Christians, we should hope and pray for everyone that they might be saved and come to the knowledge of the truth. We should hope that the number of those falling under eternal condemnation is as small as possible. But this is different that God must, or even that he will, not judge the earth and hold every human person accountable. The Fathers tell us to apply everything in scripture to ourselves, not to others. So the warnings of eternal condemnation are for me, to bring me to repentance. They are not for me to apply to other people according to my own sinful judgment.

Very helpful Father. Thank you.

Fr. Stephen,

Thank you so much for this post. It makes clear and cohesive all the issues we hear about sin, death and Christ’s victory.

I also listen to your podcasts on AFR. I have learned so much! As a cradle Greek Orthodox Christian woman who grew up in a Greek-speaking community, I thank God for individuals like you, Fr. Stephen, who have truly brought the Life of the Church and Scripture alive for us. I marvel at how much I have learned and I am soooo grateful. Thank you, Thank you!!!

May God Continue You to Bless You and Your Family – In Christ+++

Kathryn Houston

Read this now. What a wonderful text. Finally I feel I can understand these verses in the New Testament. Truly an eyeopener

Thank you Father for this! What a wonderful analogy “The ransom language is also used regarding the deliverance of Israel from Pharaoh, though Pharaoh received no payment other than a crushing defeat.” Finally I understand – Ps. 91:13 “You shall tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the serpent shall you trample under feet.” (Also ref. Gen.3) Christ did not ‘pay’ the tyrant for the slaves, then took the slaves as his own – deal done. Instead, the debt for each slave being that slave’s life, Christ enters Hades (having no debt of his own) holding LIFE itself – being God. This Life is not only sufficient to cover the debt of lives, but as Life itself it is the antithesis of death, and so death is destroyed, the slaves are free, and the tyrant crushed –epikranthi!

This is a great article, thank you for your insight. I am an inquirer of orthodoxy, as one may say, and have heard numerous times that the orthodox understanding of sin and atonement has never used “court room language” to describe this. Such as “he paid OUR debt”, “he took the payment for our sins”, etc. I was hoping you speak to this- again, I am still learning about the orthodox mindset and theology. Maybe I am misunderstanding this thought process.

Also, I come from a Protestant background. Thank you!

Have you seen the video called “The Gospel in chairs” (or something like that)? Is that an accurate description of Orthodox salvation? If Christ is paying a debt for us, then who or Who is receiving the payment? If the Hebrews were indeed ransomed from slavery and death, who or Who received that ransom? I have a hard time understanding the debt metaphor unless a being of some kind is receiving the payment of the debt.

If I were to say, “The men who stormed the beach at Normandy paid the price, with our lives, for freedom,” I think that everyone reading it would understand what I meant. This despite the fact that to ask, “Paid the price to who? Hitler? God? The Devil? How many human lives does freedom cost and how often? etc.” are incongruent questions. When the scriptures and the Fathers speak about atonement or nearly any other topic, they are describing “what” has happened or happens, not how it happened or happens. Debt and slavery are not meant to describe how Christ’s atoning death ‘worked/works’. They are meant to describe the consequences of it, what it does, in freeing us from slavery to sin and death in order to serve Christ. In the same way that my statement regarding the end of WW2 in Europe is not describing how Hitler was defeated and Western Europe was liberated, but the consequences of that liberation.

This article reminded me of the Scripture passage where Jesus says, “No to worry about the body being destroyed, but the soul.” *something to that effect…..it’s painful to lose anyone in a tragic and/or unjust way, but if we keep in mind that this is about our soul’s journey, we can accept it a little easier. Even in the case of all the horrific abortions, I believe God is doing something special with these little helpless souls…..

God bless!