To ask in the present day whether or not any book of the New Testament is truly canonical in the Orthodox Church may seem odd. While the history of the canonization process of the Old and New Testaments took place over several centuries and is neither neat nor tidy, it is an issue, particularly in the case of the New Testament, which has been settled for more than a millennium at this point. It is taken for granted that the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Protestants all share the same list of 27 canonical New Testament books. Delving into the history of the book of Revelation in particular, however, and the arguments for and against its canonicity, reveals much about the meaning of ‘canon’ when referring to Biblical texts, and the processes by which various texts and authors were received by the church over time. Even today, the question posed by the title is not one that admits of a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

To ask in the present day whether or not any book of the New Testament is truly canonical in the Orthodox Church may seem odd. While the history of the canonization process of the Old and New Testaments took place over several centuries and is neither neat nor tidy, it is an issue, particularly in the case of the New Testament, which has been settled for more than a millennium at this point. It is taken for granted that the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Protestants all share the same list of 27 canonical New Testament books. Delving into the history of the book of Revelation in particular, however, and the arguments for and against its canonicity, reveals much about the meaning of ‘canon’ when referring to Biblical texts, and the processes by which various texts and authors were received by the church over time. Even today, the question posed by the title is not one that admits of a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

The most common argument for a positive answer to this question is simply to point to the book of Revelation’s presence in Orthodox Bibles. This, however, assumes a particular view of canonicity. Namely, it assumes that the canon of scriptures is essentially a table of contents for a book, the Bible. Despite this being a common presupposition of Roman Catholic apologists, and often borrowed by Orthodox people in debate with Protestants, it is problematic on two counts. First, thinking of the scriptures as a single book between two covers, the Bible, is relatively recent. It may be noted that to this day, the scriptures in the Orthodox Church are not read from a Bible. Complete Bibles were extremely rare before the advent of the printing press. Instead, there were codices of the gospels or of the epistles. And these were just as often in lectionary form as in continuous form. So while it is very common and simple for us to talk about ‘the Bible’ as a unit containing all of the canonical scriptures with a table of contents in the front listing the books, this is not how our forebears in the faith interacted with and understood the scriptures, particularly in the time period during which canonization was taking place. Second, there simply is no time when the Orthodox Church as a unit listed a prescriptive table of contents for an ‘Orthodox Bible’. Rome issued such a list, but not until the Council of Trent in the 16th century, when various Protestant groups issued their own lists in their confessional documents. Before this, in both East and West, there were books which were used and books which were not used by various local churches. There are, certainly, canon lists in the early church, issued by local councils in some cases, or possibly most famously St. Athanasius’ Paschal Letter of 367. These lists, however, were not telling the local churches to which they were directed which books ought be in their Bibles, in a prescriptive way, but rather to command those local churches, in their various congregations, to leave off the public reading of certain other texts which had found their way into those churches. Further, despite the fact that St. Athanasius includes Revelation on his list of texts in the Paschal Letter, when Ss. Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom gives lists of New Testament texts in the following generation, Revelation is notably absent.

The strongest evidence that the book of Revelation is not canonical in the Orthodox Church is that it is not publicly read in the Orthodox Church. The only exceptions to this are some Alexandrian churches and the monastery on the Isle of Patmos itself. Following the lectionary of the Orthodox Church, one reads through the entirety of the New Testament each year, except for the book of Revelation. This argument has the advantage of using language parallel to that used by the Fathers during the canonization process. The discussion was not over which books ‘belonged in the Bible’ but which books were read publicly in the churches. Further, in the discussions of these issues that took place in the Christian East, canonicity was not a binary category, ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Rather, there were three categories: books to be read in the churches, books to be read in the home, and books not to be read. This argument therefore is not to attack Revelation as heretical or false, but only to argue that in the Orthodox Church it has a status similar to that of the Apostolic Fathers. Orthodox, important, useful, and even authoritative to a degree, but not a part of the New Testament as such. The difficulties here are again twofold. First, there are the exceptions previously mentioned, in which canonical Orthodox churches read Revelation publicly as scripture. Second, when one examines the historical discussion concerning the book of Revelation in the early church both East and West, these are not the terms of the debate. There were local churches which accepted Revelation as scripture, and those which rejected it utterly, and no offer of a compromise in between. While the discussion of, for example, the Shepherd of Hermas was one of level of authority, with even those who rejected its public liturgical reading still reading it and citing it authoritatively, the book of Revelation was clearly, to all parties, someone’s scripture. The question was, “Whose?”

The church at this time did not have a central authority. Rather, it consisted of local churches, spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, which existed in a state of communion with one another, recognizing each other as sharing the same Lord, the same faith, and the same baptism. This communion came to be, and grew, through mutual encounter between these communities over time, and the canonization process is to be found historically in these encounters, as one factor in these encounters was the comparison of what texts held authority in the respective communities. Another community was either part of the body of Christ, or a part of a heresy. This latter word, ‘airese’ in Greek, in its use in this period, meant a ‘sect’ or a ‘faction’ or ‘school of thought’. If a local church that read from the four Gospels and St. Paul’s epistles in worship encountered another local church that read from the same texts, but perhaps also from St. James’ epistle and 1 Peter, they would likely recognize them as another part of Christ’s body, whether or not they decided to start reading from those books themselves. If, on the other hand, they encountered a group reading from Plato’s Timaeus, the Gospel of Truth, and the Gospel of Mary, they would identify this group as part of a heresy. The latter two of these texts were scriptures, and could even be called canonical in the communities that read from them, but they were not Christian scriptures, and they were not canonical in Christ’s church.

Judging by the writings which we currently possess from the second century Fathers, one would get the impression that the book of Revelation was one of the least controversial. It must be remembered, however, that the vast majority of the second century Fathers whose writings have survived, despite representing a geographic spread across the Roman Empire, are all Fathers theologically trained in the Johannine circle in Western Asia Minor by St. John himself, or his immediate disciples. It should, therefore, be unsurprising that Ss. Irenaeus and Justin, for example, place the book of Revelation alongside St. John’s Gospel and at least the first of his epistles as scripture quite readily. There were therefore, without doubt, local churches in which Revelation was read as scripture from the early to mid second century. What created the controversy over the book of Revelation, which would last for centuries, was not that there were other local churches in which it was not read. Rather, it was caused by the emergence of a heresy which embraced the book of Revelation.

Montanism is a heresy which arose at the end of the second century, named after Montanus, its founder. This Montanus claimed that he was the paraclete who Christ promised would come after him, and along with two female prophetess’s, claimed to produce further revelation of God. Montanism began in Asia Minor, in Phrygia, and was sometimes called the ‘Phrygian heresy’. Though it is likely incidental to his other beliefs, Montanus, like the Orthodox of the second century in Asia Minor, saw the book of Revelation as scripture, and was a chiliast. Chiliasm in the ancient church needs to be defined and differentiated from modern premillennialism. Chiliasm was the belief that there would be a thousand year reign of Christ, on this earth, over Christians in an earthly paradise of material wealth and opulence. Unlike premillennialism in our modern day, it had no connection to the idea of ethnic Israel being a separate people from the Church and the need for certain prophetic promises to be fulfilled for them in a material way. Even Fathers such as Ss. Justin and Irenaeus from this region seem to have held to chiliastic views. A surface reading of Revelation 20 seems to lend itself to chiliastic interpretation, and so, beginning in the third century as the church pushed back against Montanism, it also pushed back against chiliasm, and in the process, against the book of Revelation.

This created a tension over the book of Revelation that lasted for centuries. While there were still local churches who read Revelation as scripture, and Fathers who cited Revelation authoritatively, generally avoiding chapter 20, there were strong voices of other Fathers who, believing that Revelation taught chiliasm, rejected it and argued that it should not be read. Additionally, chiliasts embraced this characterization of the book of Revelation, composing a large volume of commentaries on the text. This tension put Eusebius, for example, to great pains in describing the history of the text, such that he felt the need to parse the testimony of Papias with that of St. Irenaeus to try to separate Revelation from St. John’s Gospel. The eventual acceptance came about through the efforts of two saints, one in the East, and the other in the West. In the West, a certain Victorinus produced a full length commentary on the book of Revelation. This commentary was highly regarded for its insight in many passages despite Victorinus being a chiliast. Recognizing its value, St. Jerome heavily edited Victorinus’ commentary, removing any whiff of chiliasm, and reissued it under his own name. Importantly, this took place during the period when the Latin liturgical tradition was coalescing, allowing the book of Revelation to enter fully into Western liturgical life.

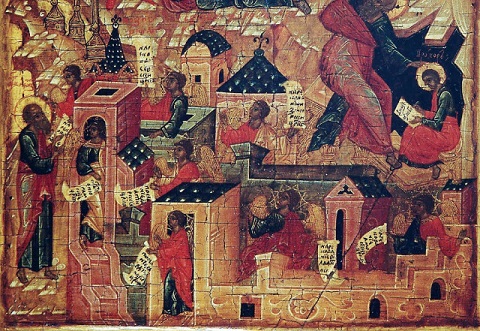

In the East, the book of Revelation, outside of North Africa, remained largely associated with chiliasm and therefore rejected for another century. In the mid-sixth century, a certain Oikoumenos (or Oecumenius), a chiliast, wrote a full-length commentary on Revelation in Greek. Like that of Victorinus, this commentary was perceived as being very valuable in several passages regarding the text. In a manner similar to that of St. Jerome, St. Andrew of Caesarea revised, expanded, and popularized this commentary under his own name. The situation of the East in the sixth century differed from that of the West in the fifth, however, in distinctive ways. The liturgical traditions of the East were already long established by this point, including the lectionary tradition. Further, St. Andrew, though an important figure, did not play the pivotal role in the formation of the Greek liturgical and scriptural tradition that St. Jerome did in the Latin tradition. St. Andrew’s reading of Revelation, therefore, gained wide acceptance through its quality and clarity, not through the perceived authority of St. Andrew himself, and so this process took two centuries. Even in the latter part of the seventh century, for example, St. Maximus the Confessor rejected Revelation’s canonical status. Over the course of those two centuries, however, St. Andrew’s commentary came to be embraced by the entirety of the Orthodox Church, and through it, the book of Revelation itself. To this day, Orthodox commentaries on Revelation amount to commentaries on St. Andrew’s commentary. This reveals another way in which Revelation is unique among Biblical texts in the Orthodox Church, in that it is the only New Testament text that is canonical by virtue of having a very particular canonical interpretation.

I once heard someone say (I wish I could remember whom) that Revelation wasn’t read in the church because it is enacted at every liturgy. I don’t know how commonly that view is held but it was helpful to me as an ex-Protestant to see Revelation in a very different light.

How did the early Protestant reformers view Revelation? I know Luther didn’t much care for the Epistles of James and John and only reluctantly included them, but I’m not sure what he or his contemporaries like Zwingli and Calvin thought of Revelation.

I know Calvin didn’t write a commentary on Revelation… but I don’t know what he thought about its canonicity

Luther essentially regarded the book of Revelation, along with a few of the general epistles, as New Testament apocrypha. There were several other figures of his generation who took the same approach. They were included in Bibles, but sectioned off in the same way that the Old Testament ‘apocrypha’ was. Calvin viewed it as canonical, but only commented on the first several chapters, at which point he stopped because he said that everything after that was conjecture. There were already in the West at that point people trying to bring the imagery of Revelation into line with then current events because they believed they were in the end times. That continued well into the Puritan era. Jonathan Edwards on Revelation, for example, is bizarre and somewhat fascinating.

Is St. Andrew’s commentary available in English?

It is: https://www.amazon.com/Greek-Commentaries-Revelation-Ancient-Christian/dp/0830829083/

Excellent presentation on the history of Revelation and how it finally gained canonical status in the Church. Thank you!

In response to certain comments, I am aware that the ‘Great Reading’ of all night vigil services includes the book of Revelation. The ‘Great Reading’, however, is not the lectionary. It is lectio continua. This is because it is prescribed as a sort of break from the liturgical celebration of the vigil. This prescription to read continuously through the New Testament in the Sabbaite Typikon dates to centuries after St. Andrew of Caesarea. If the piece above is read in its entirety, it should be clear that nothing here contradicts this. The topic under discussion is how the book of Revelation came to be recognized as canonical in the East, and why it appears is the Western, but not the Eastern lectionary.

This is insightful, I didn’t know anything about the history of Revelation besides it being written by Saint John. I see how/why it is canonical, and how it has contributed to our liturgical hymns. I have a bunch of questions: Since this was a dream Saint John had/a vision, all of the symbolism within the vision may not be applicable today, or make sense to us. Since it was a dream/vision, should we take it as something concrete and literal? I lean towards no, not completely, but I am open to learn why that is not the correct way to think about this scripture. Is it acceptable to read it and interpret it as a parable, like other lessons in the Bible? A lesson about being prepared for God when He comes, not something that is absolutely going to happen exactly how it’s written? The history of when it was written is mainly what brings those questions up for me. How can we make sense of the symbolism in a way that maintains our Church’s other beliefs and make sense to us now?

I have difficulty understanding the parts about eternal condemnation especially. Mentioning Revelation usually brings up heated discussion about “who will be damned,” which I’ve always been told is unhelpful. Nobody knows, so we shouldn’t be saying who will/won’t be with God in the end, nor should we tie Revelation into current events. Perhaps that is one reason Revelation is a touchy subject, since we would all prefer to know if we will be condemned or with God. I have a lot of doubt about what Saint John envisioned, and that is kind of scary because I consider myself an Orthodox Christian in “good standing.” I believe in what I say when I recite The Creed, for instance, which includes God coming to judge the living and the dead.