Concepts of justice in the contemporary world are varied. Likely the most prominent usage of the term is related to criminal justice. In the United States, the Department of Justice is considered to be the preeminent law enforcement authority in the land. This understanding of justice is focused on the punishment of criminals in proportion to their crimes. When an offender receives their due punishment, justice has been done. If a guilty person goes free or an innocent one is punished, this is injustice in the truest sense. In its ideal form, justice, as expressed in common statuary, ought to be blind. It ought not to take into account a person’s relative wealth, rank, or station in life. It ought to only let the punishment fit the crime. Multiple factors are considered with regard to apportioning punishment to crimes, including various combinations of deterrence, the reduction of recidivism, and even the idea that the infliction of suffering somehow atones for wrongdoing.

Concepts of justice in the contemporary world are varied. Likely the most prominent usage of the term is related to criminal justice. In the United States, the Department of Justice is considered to be the preeminent law enforcement authority in the land. This understanding of justice is focused on the punishment of criminals in proportion to their crimes. When an offender receives their due punishment, justice has been done. If a guilty person goes free or an innocent one is punished, this is injustice in the truest sense. In its ideal form, justice, as expressed in common statuary, ought to be blind. It ought not to take into account a person’s relative wealth, rank, or station in life. It ought to only let the punishment fit the crime. Multiple factors are considered with regard to apportioning punishment to crimes, including various combinations of deterrence, the reduction of recidivism, and even the idea that the infliction of suffering somehow atones for wrongdoing.

Criminal justice is commonly known as “retributive justice.” The retribution is the punishment that is bestowed in response to the crime. Even confining inquiry to court systems, there is a second type of justice, “distributive justice.” In a general sense, distributive justice does not deal with punishing wrongdoers. Rather, it is concerned with making the victims of the wrong whole. If one person has harmed another or another’s property, then the one guilty of harm is required by justice to forfeit his own property to compensate for the damages. This is true in cases of both maliciousness and negligence. From the perspective of a perpetrator, distributive justice may be indistinguishable from retribution, as the perpetrator’s suffered loss may be viewed as a punishment. From the perspective of the victim, however, it is aimed at a concrete amelioration of suffering, rather than a simple appeal to a sense of justice and fairness.

Recently, a burgeoning amount of consideration has been given to the subject of “social justice.” Rather than focusing on the individual actions of individual people and their immediate consequences, social justice focuses on large structures within communities, cultures, and nations. These structures and thought-forms have consequences for those who live and operate within them. As imperfect human structures, these consequences will tend to accrue in the negative to some people and in the positive to others. If the factor controlling these consequences is directly proportional to virtue, most communities will find them acceptable. If these structures are found, rather, to give benefit or inflict harm based on an individual’s race, nationality, gender, age, or relative wealth, for example, the structures themselves will be seen to be unjust. Just as this sort of favoritism from one charged with enforcing the law would be unacceptable, so also is it unacceptable for this favoritism to be codified within the law itself or the functioning of the institutions which define and enforce it. These structures need to be corrected in order to establish justice within and for the community.

All three of these forms of justice are found within the commandments of the Torah in Scripture. Certain sins are considered to be particularly abominable, chiefly idolatry, sexual immorality, and murder and so the perpetrators must be permanently removed from the community (e.g., Num 15:30-31). Certain objects, generally those used in the practices above, fall under the ban and must be destroyed (e.g., Deut 7:25; 12:3). For most crimes and disputes within the community, the Torah prescribes restitution from the perpetrator toward the victim. Thieves must repay what they have stolen (e.g., Ex 22:1-4). Damaged or destroyed property must be replaced. Finally, specific commands seek to ensure that societal structures do not become oppressive. The Jubilee year requires the manumission of slaves and the restoration of lands to the families which originally owned them (Lev 25:8-13). This command, if followed, would have prevented generational poverty and slavery.

All of these conceptions of justice and the relevant commandments and laws are taken up in the concept of justice as expressed in the Hebrew Scriptures. The Hebrew word generally translated as ‘justice’ is ‘mishpat’. This term contains the idea of a region of space and time in which all things are in their proper place and are related to one another in the correct way. Deviations from this state constitute injustice. The commandments of the Torah are intended to serve as a guide for preventing such injustices from occurring and also to prescribe means for correcting such injustices when they do occur. To correct these injustices and restore the state of justice is to judge (Hebrew ‘shafat’).

God’s justice is also one of the divine energies. God is just and is continuously working in His creation in order to bring about and preserve this state of justice. Therefore, for a human person or a human community to live in a way that is in keeping with the justice of the Triune God is to participate in His operation within creation. This participation is transformative and produces a state of blessing. ‘To bless’, as a verb, is then to bring the person or thing blessed into alignment with God and His purposes in creation.

Likewise, for a human person or a human community to live in a way that is unjust, which runs against the way in which God is operative within His created order, is to produce corruption. This rebellion is also transformative and produces a state of curse. When someone or something is cursed, it is removed or broken out of the system of relationships that constitute justice in the world. So Cain, after committing murder, is cursed from the earth and is no longer able to interact with created nature in agriculture (Gen 4:11-12). Throughout the Old Testament, curse entails banishment from the community and the place where God dwells.

In the Ancient Near East, the cultural context from which the Scriptures emerge, the primary purpose and task of the king were to establish and maintain justice. For Israel’s neighbors, this included harmony and peace with the gods, the spiritual beings who were seen to be a part of the community. Kings were therefore also priests, up to and including the Roman emperor who served as ‘pontifex maximus’, or high priest, of the sacrificial rites. Sacrifices offered by kings and other community leaders and heads of families were communal meals aimed at uniting the community with one another and with their gods. For this reason, the king himself was seen to be divine and therefore able to bridge the visible and invisible worlds.

This role of the Pharaoh, for example, stands in the background of the ten plagues sent upon the land of Egypt (Ex 7-12). The plagues are portrayed in the book of Exodus as warfare between Yahweh and the gods of Egypt. These gods have been complicit in the slavery and abuse of the Hebrew people and countless other injustices. Therefore, their defeat by Yahweh is their judgment (Ex 12:12). Throughout this judgment, however, it is Pharaoh who is the interlocutor. He is the one who is expected by the Egyptian people to restore justice and peace in the face of plague and curse but is utterly unable. His scribal priests, the “magicians” of English translations, are completely unable to assist him as experts on interfacing with the spiritual world in general and the gods in particular (Ex 7:10-12, 22; 8:7, 18).

Within Israel, the relationship between Yahweh, the high priest, and the eventual kings was different. The leadership of Israel began with Moses, then Joshua, then the judges, and finally the kings. Their task was not to mollify or manipulate God but rather, as His servant and image, to establish His justice in Israel. This is why, though they did not hear trials or cases, the judges are known by that title. Throughout the book of Judges, through rebellion and injustice, Israel and her various tribal units brought down a curse upon themselves which typically manifested itself as foreign domination. God then raised up a judge in response to their repentance to reestablish justice in the land.

While the role of the leadership, including the king, was to establish justice by bringing about obedience to the commandments, the priesthood was concerned with justice in another sense. The most obvious form which this took was the restoration of justice following injustice through the rites of repentance and atonement. These purificatory rites staved off the curse and exile which would result from allowing sin and injustice to fester within the community. The priesthood also, however, related to divine justice in a positive sense. The offerings of thanksgiving formed the core of the daily sacrificial rites related to the offering of incense and other offerings. These rites served to bring worshippers more deeply into positive participation in God’s operations within His creation, including His justice.

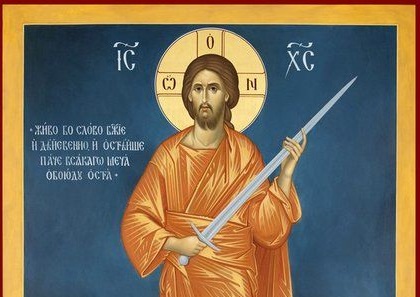

The state of justice, then, is the original state of the created order. In fact, it is the order that constitutes God’s creative act against chaos. The lasting rest and peace of the age to come, an age without end, will be ordered by divine justice. Sin, suffering, and death in this age are the result of the violation of this order in creation. Because that order represents the activity of the Triune God, such a violation is also rebellion, which brings about destruction. As the divine king, Christ is the minister of this justice, the one who judges (John 5:22). His reign is one of both threat and promise.

Dear Fr. Stephen De Young! I prayed and always praise God for the ministry your are doing. I am one your frequent followers of your blog and your podcast. They way you explain things is answering my question. I believe that God is answers tons of questions i had for decade. May God bless your ministry.

Do you mind writing on details about righteousness? how justice is related with being jestified in Christ? The relation between justice and righteousness? Righteousness from both old testament and newtestament perspectives?