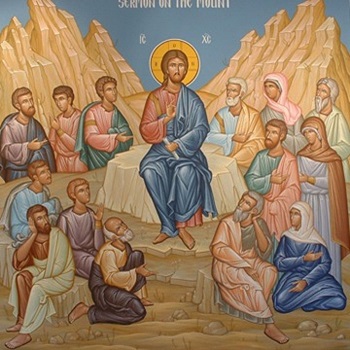

The Beatitudes (Matt 5:1-12) form a prologue or introduction to Christ’s Sermon on the Mount in St. Matthew’s Gospel. The corresponding blessings, but in this case with accompanying woes, play a similar role in the Sermon on the Plain found in St. Luke’s Gospel (Luke 6:20-26). Often these blessings are extracted from the surrounding material in much the same way that the Ten Commandments are extracted from the other commandments of the Torah as a sort of summary. Like the Ten Commandments, they are often memorized. They are sung or recited at several points in the liturgical worship of the Orthodox Church, including within the funeral services. The word ‘Beatitude’ is a transliteration of the Latin ‘beatitudo‘ which refers to a state of happiness, good fortune, or blessedness. English Bible teachers, as a learning device, often split the word, saying that these are ‘Be-attitudes’, attitudes or forms of behavior that Christians ought to foster. This is a clue as to how these are often interpreted, i.e. as a series of ethical principles to be obeyed. The woes in Luke, then, though less often discussed, would represent unethical forms of behavior to be avoided.

The Beatitudes (Matt 5:1-12) form a prologue or introduction to Christ’s Sermon on the Mount in St. Matthew’s Gospel. The corresponding blessings, but in this case with accompanying woes, play a similar role in the Sermon on the Plain found in St. Luke’s Gospel (Luke 6:20-26). Often these blessings are extracted from the surrounding material in much the same way that the Ten Commandments are extracted from the other commandments of the Torah as a sort of summary. Like the Ten Commandments, they are often memorized. They are sung or recited at several points in the liturgical worship of the Orthodox Church, including within the funeral services. The word ‘Beatitude’ is a transliteration of the Latin ‘beatitudo‘ which refers to a state of happiness, good fortune, or blessedness. English Bible teachers, as a learning device, often split the word, saying that these are ‘Be-attitudes’, attitudes or forms of behavior that Christians ought to foster. This is a clue as to how these are often interpreted, i.e. as a series of ethical principles to be obeyed. The woes in Luke, then, though less often discussed, would represent unethical forms of behavior to be avoided.

This presumes a primarily legal structure to what might be called ‘Biblical ethics’. Certainly, that is in keeping with the common English translation of Torah as ‘the Law’. Christ’s delivery of these Beatitudes from a mountain top as well as a number of other features of the Sermon on the Mount as a whole clearly allude to a connection between his teaching in the sermon and that received through Moses. Just as the legal interpretation of the Torah distorts the revelation of the God of Israel, so also reducing the teaching of Christ solely to the level of a legal ethic distorts what he seeks to communicate. As will be seen, when Christ describes life in the kingdom, he is not describing an ethical way of living life on earth or of being a good person. Rather, he is describing the eschatological life of the age and world to come, a life which begins in this present world and continues into eternity. Likewise, the woes of St. Luke’s account describe a life of eternal condemnation which likewise begins in the life of this world and age. The life in the kingdom described by the Beatitudes is another way of speaking of what St. John calls ‘eternal life’ (John 3:15-16, 36; 4:14, 36; 5:24, 39; 6:27, 40, 47, 54, 60, 68; 10:28; 12:25, 50; 17:2-3).

Though nearly universally translated in English as ‘blessed’, the Greek word which begins each of the Beatitudes is not a form of ‘evlogeo‘, the usual Greek word for blessing someone or something. This understanding of blessing is used throughout all three Synoptic Gospels to describe a relational category. When used of people, it is generally used to describe that person being in a relationship of favor with God or to invoke divine favor upon a person (Matt 5:44; 21:9; 23:39; 25:34; Mark 10:16; 11:9; Luke 1:42; 2:34; 6:28; 13:35; 19:38; 24:50-51). When used of an object, it indicates that the object is being removed from its relationships in the sinful world and restored to its created state and order (Matt 14:19; 26:26; Mark 6:41; 8:7; 14:22; Luke 9:16; 24:30). Occasionally, the term is also used directed from humans to God, in which case it is a way of indicating favor and honor by analogy, the offering of praise to God (Mark 11:10; Luke 1:64; 2:28; 24:53). Though both St. Matthew and St. Luke freely use this term, it is not the ‘blessed’ of the Beatitudes. This moves one common reading of the Beatitudes off of the table. The Beatitudes are not saying that a certain behavior or way of life will bring God’s favor and result in him giving an enumerated gift. I.e. it is not saying, for example, that if one is meek, God will be pleased with him and give him the earth as a reward. The Gospel writers had the vocabulary close at hand to say that, and did not.

The word used in the Beatitudes is, rather, ‘makarios‘. This Greek term had a long pre-Biblical history. It refers not to a relationship between things but to a state of being marked by happiness or bliss. This is a word that was often used in the Classical period to describe the life of the gods. Over several centuries, that usage led to it becoming a respectful way to refer to the recently deceased, implying something similar to, in our modern parlance, that they’d “gone to heaven” or they were “with the angels.” In its use in the New Testament, not only in the Beatitudes themselves, the term retains this spiritual force. To be blessed in this sense is to be experiencing the bliss and happiness that come from sharing the life of God. From the perspective of Greek paganism, one participated in this divine life through sexual and other indulgences, through prosperity and leisure, and through the acquisition and of power and victory. In the Beatitudes, Christ reorients, indeed, inverts what it looks like to share in that life in this world and this age while maintaining in its fullness what that means in the age and world to come.

The term ‘makarios‘ is used in other New Testament texts in the same way. The Apocalypse of St. John uses the term frequently to describe the state of eternal life, possessed by both the living and the dead in Christ (Rev 1:3; 14:13; 16:15; 19:9; 20:6; 22:7, 14). St. Paul uses the term to describe the life of God (1 Tim 1:11; 6:15). He also uses it as a description of the Christian hope for the life of the world to come (Tit 2:13). Recognizing this term is important to understand the argument of St. James’ epistle. He states that the one who hears the Torah and truly keeps it will be blessed (makarios) in all that he does (Jam 1:25). He is not here claiming that if one keeps the commandments perfectly they will have health, wealth, and success. Rather, he is saying that throughout a person’s life, in everything that person does, if they keep the commandments they will experience the peace, joy, and bliss of knowing God regardless of life’s circumstances.

Though lacking the corresponding woes, St. Matthew’s listing of the Beatitudes has long been considered normative because of its fullness. Several, but not all, are paralleled in St. Luke’s account and even these are not identical in both Gospels. The Beatitudes follow the same pattern. They each state that a certain group defined by a particular characteristic is experiencing this state of divine happiness and bliss because a certain destiny awaits them in the future. Basic to this construction is the idea that the state of happiness and bliss is present now, but that the destiny described is a future state. This structure reinforces that the state of ‘blessedness’ here is not marked by prosperity in this age. Rather, it represents an intrusion, a foretaste, a beginning of that future destiny of happiness and bliss in this present age that finds its fulness in the age to come.

The description of future destiny within the Beatitudes very clearly matches the Second Temple conception of the life of the age to come. The bliss of the age to come is described as possession of the reign or dominion of heaven. It is described as receiving the earth as an inheritance. It is described as being filled with justice or righteousness. It is described as having the vision of God. It is described as being ranked as sons of God. It is described as a great reward in the heavenly places. All of these are imagery used throughout Scripture to describe sharing in the reign of God over the entire creation as his kingdom. The angels of God’s divine council are called the sons of God. They are given to share in his rule, to participate in his administration of the cosmos. Humans, in Christ, become co-heirs with him who share in his inheritance. They receive mercy before his judgment seat and become judges themselves. Those who attain the age to come and the resurrection of the dead cannot die any more and are equal to the angels and sons of God (Luke 20:35-36).

However, Christ teaches that those who experience the beginnings of this destiny in the present world are not the prosperous, the wealthy, the powerful, and the victorious. Rather, they are those who, despite being in the Spirit, are poor. They are those who mourn losses. They are those who are humble. They are those who hunger and thirst for justice which eludes them in this world. They are those not who conquer but who show mercy. They are those whose heart has been cleansed of former stain. They are those who make peace, not those who emerge victorious and powerful through conflict. They are those who suffer persecution for the sake of behaving justly. They are those who are hated, mocked, and even slain for the sake of Christ’s name. These are not those who were seen by ancient cultures to be living the best human life, let alone the life of the gods. These are those whom the ancients saw as unworthy at best or at worst, under a curse.

St. Luke makes the contrast between ancient understanding and Christ’s teaching even more explicit by paralleling a shortened list of the Beatitudes with a series of woes. The poor are happy but the rich are under a curse. The hungry are blissful but the full are accursed. Those who weep are blessed but those who laugh are doomed. Those who are hated, excluded, mocked, and derided are experiencing the divine life, while those who are of good reputation and spoken of well by all are damned already. The just, the faithful, those who are in Christ have a glorious destiny which of which they already partake in this life regardless of this life’s circumstances and the hardships they here endure. For St. Luke, those who enjoy success, prosperity, wealth, and power in this life do so through wickedness and are on a trajectory that leads not to eternal life, but to death, curse, and condemnation in the age to come, an age which has no end.

The gospel is the story of Christ’s victory over the powers of evil, the principalities and powers in the heavenly places, sin, death, and Hades. The four written Gospels are the story of that victory according to the four evangelists. The Beatitudes describe the destiny of humanity, the inheritance, the glory that is won by our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ through that victory. They not only describe what we call theosis, becoming like God, coming to share in the eternal divine life, but they contain a promise. Not only a promise for the future, that one day the faithful who are in Christ will come to share in his rule and dominion over all of creation as sons of God, but that the happiness, the bliss, the joy of that future existence will be partaken of in this life, in this world. Those who are in Christ experience life in this age with all of its struggles and trials and hardships. But they face these hardships indwelt by the Holy Spirit, who is God himself and who is the downpayment on the inheritance to come (2 Cor 1:21-22; Eph 1:14). Despite all of those troubles, the Spirit bears the fruit of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Therefore those who are in Christ have no fear because Christ is victorious over this present age (John 16:33).

Thank you Fr Stephen, yet another very illuminating article from you. The Beatitudes seems to be a ‘well of knowledge’ on how to understand and keep the Word of God.

There are so many different translations of Holy Scripture. It is not easy for a lay person to make sense of what is written, so to have someone who can explain the true meaning of the original texts and what the Greek, or Hebrew, word meant at the time, is truly blessed.

The tendency to interpret things in a purely legalistic way is very dominant, and it restricts us to look only at appearances. The cost for doing that is very high.

Yes, very high indeed. Lord, have mercy on me a sinner.

Thank you for this father. This echoes things I’ve been reading elsewhere on how we often confuse the Christian life with the moral life. Not that being moral is not important, but that it’s an outflow of the Life of God within us, not the other way around. As Fr. Stephen Freeman often says, “God did not die to make bad men good, but to make dead men live!”

I’ve remarked to my priest on more than one occasion that it wasn’t until becoming Orthodox that I began to wonder if I was suffering enough. I think about it often, particularly in the context of my pretty comfortable middle class American life. Very little of the life I have could be referred to as ‘suffering’. I’m clothed, housed, well fed, gainfully employed and surrounded by loving family. Again, counter-intuitively, I find this often causes me concern about whether I’m truly on the path of repentance and life. If the fullness of my sins was made clear to me, I’d probably fall on my face before my Icons, weeping bitterly until the day I died. But that’s not where I find myself now and I don’t know whether or how I get there.

Not exactly the “Be happy attitudes” of Robert Schuller!

Father, thanks for a great article. How is the state of makarios differentiated from eudaeimonia?

Eudaimonia is more related to success, prosperity, and goodness of a life lived in this world. Its the primary term used, for example, in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics to describe the goal of an ethical or moral life. So it lacks the eschatological element that’s found in Christ’s preaching as exemplified by the Beatitudes.

Thank you so much.

I love so much the beatitudes and am used to reading the real justice of God in them. The real character of Chrit Himself.

Your post made my week. I better understand how this sermon is so beautiful, so great, so helpful.

Thanks again