One issue of more than occasional discussion and tension within the Orthodox Church is the way in which persons are received into the church who have been baptized, whether as infants or adults, in some context or polity other than the Orthodox Church herself. This debate tends to take place regarding whether in certain cases, certain persons so baptized ought to be received through chrismation. Those supporting this approach reference its long history of usage and application in the Orthodox Church under a variety of circumstances in receiving persons from a variety of different backgrounds. Opponents of this practice generally argue that not baptizing such a person within the Orthodox Church is tantamount to lending some sort of recognition of validity to the baptismal ritual as practiced by other groups. This would seem especially problematic when baptism is “accepted” from a group that has a view of what baptism is and does that is different from the understanding of the Orthodox Church. It is generally assumed that this is primarily a contemporary problem or at least a problem which, while faced occasionally in centuries past, has become far more prevalent in our contemporary era. Certainly, the Orthodox Church now exists in many nations on an ongoing basis with many more groups that identify themselves as Christian and practice some form of baptismal ritual. Within the pages of the New Testament, however, the apostles themselves existed in a culture in which there were many different initiation rituals and ritual washings practiced by various religious groups and, indeed, more than one baptism.

One issue of more than occasional discussion and tension within the Orthodox Church is the way in which persons are received into the church who have been baptized, whether as infants or adults, in some context or polity other than the Orthodox Church herself. This debate tends to take place regarding whether in certain cases, certain persons so baptized ought to be received through chrismation. Those supporting this approach reference its long history of usage and application in the Orthodox Church under a variety of circumstances in receiving persons from a variety of different backgrounds. Opponents of this practice generally argue that not baptizing such a person within the Orthodox Church is tantamount to lending some sort of recognition of validity to the baptismal ritual as practiced by other groups. This would seem especially problematic when baptism is “accepted” from a group that has a view of what baptism is and does that is different from the understanding of the Orthodox Church. It is generally assumed that this is primarily a contemporary problem or at least a problem which, while faced occasionally in centuries past, has become far more prevalent in our contemporary era. Certainly, the Orthodox Church now exists in many nations on an ongoing basis with many more groups that identify themselves as Christian and practice some form of baptismal ritual. Within the pages of the New Testament, however, the apostles themselves existed in a culture in which there were many different initiation rituals and ritual washings practiced by various religious groups and, indeed, more than one baptism.

At the very beginning of the Gospels’ witness, a distinction is made between two different baptisms. The first is the baptism instituted and administered by St. John the Forerunner and along with him a few of his disciples. In all four Gospels, St. John himself distinguishes between his baptism and the baptism of the one who is coming. St. John’s baptism was a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. It is a baptism performed with water. The baptism of Christ, on the other hand, would be with the Holy Spirit and with fire (Matt 3:11; Luke 3:16; Mark 1:8; John 1:31-33). This distinction explicitly occurs within the context of St. John professing the superiority of the Christ who is coming into the world over himself. The baptism of Christ, then, is greater than that of St. John within a paradigm of fulfillment. As Forerunner, St. John’s ministry is preparatory and finds its fulfillment in that of Christ. Likewise, his baptism in Christ’s baptism which fills up to overflowing what St. John’s baptism accomplished.

St. John’s baptism did two things ritually. The first, as stated in these Gospel passages, was that it served as a form of ritual repentance bringing about the forgiveness of sins. St. John presented it as a greater and more efficacious form of the ritual washings practiced within the larger Second Temple community which happened repeatedly in order to restore from a state of uncleanness, either ritual or moral. The Pharisees, as just one example, rejected St. John’s baptism because they felt that for them it was unnecessary as they held themselves to have fulfilled all the requirements of the Torah and therefore require no further purification (Luke 7:30; Matt 21:25-27). St. John’s baptism deals with what could be called the negative aspect of sin, the damage done to the human person, and the remaining taint and state of curse resulting from human sinfulness. It restores its recipients to a state of purity which prepares them to come into the presence of the God of Israel safely or, in this case, have the God of Israel come into theirs (cf. Ex 19:10-11).

St. John proclaimed the necessity of this purification from sin based on the coming visit of God in judgment (Matt 3:7-10; Luke 3:7-9). Modern people tend to think of judgment primarily in individual terms and so these statements by St. John are read in that light, as presenting his baptism as a necessary rite pertaining to a person’s eternal destiny after death. Within its original, ancient context, however, the concept of person functioned within the concept of community. This is the second, equally important element of St. John’s baptism. It functions to actualize membership within a particular community, the remnant of Israel. This remnant is not understood as merely consisting of the descendants of Abraham who maintained their ethnic identity through Babylonian exile as well as Greek and Roman oppression. Rather, this is a group preserved by Yahweh the God of Israel throughout Israel’s history. The first and most notable reference to the preservation of this group came during the ministry of the Prophet Elijah (1 Kgs 19:18), though it became a common element of the prophetic witness regarding the latter days. St. Paul appeals to this element of St. Elias’ ministry in continuity with his own understanding of the composition of the Church as the renewed Israel (Rom 11:4). This forms an element of St. John’s identification with Elijah.

It is also important to note that this community aspect of St. John’s baptism is exclusionary rather than inclusionary by his own testimony. Receiving St. John’s baptism does not make a person a member of a community that St. John is seeking to create de novo. He does not present himself as the leader or founder of a new “sect of Judaism” to use modern terminology. There were many different groups in the Second Temple period that fit this profile, that at Qumran being the most well known. St. John did not baptize people in order to include them in a new movement. Rather, St. John proclaims that those who fail to receive his baptism will exclude themselves from the remnant of Israel. The grounds of judgment that St. John proposes is the production of fruits of repentance. His baptism is the ritual enactment of repentance from which those fruits will proceed. Refusing, then, to submit to his baptism was an act of unfaithfulness which cut a person off from the root of Abraham’s faithfulness. St. Paul’s treatment of this topic in Romans 11 is an explanation and development of what St. John himself proclaimed during his ministry.

The baptism of Christ, then, is a fulfillment of that of St. John in both of these aspects. The baptism of Christ is characterized by St. John as being with the Holy Spirit and with fire. That fire is the same fire which he says will consume the fruitless branches. The judgment which St. John proclaims as coming soon and in light of which persons must be baptized in repentance is enacted through the baptism of Christ. Judgment is the restoration of a state of justice, of the right ordering of things. The fire of the Holy Spirit brought to bear in baptism is a purifying and refining fire, consuming that which is unworthy and purifying what is precious. To be judged in this context is, therefore, to be set right, to be justified. St. John’s baptism is not superseded or replaced by that of Christ. Rather, the former is preparatory to the latter and the latter fulfills and completes the former. While baptism with water brings about new birth and thereby a return to innocence, the baptism of the Holy Spirit is empowering and initiates a new mode of life and mission in the world (cf. 1 Sam/1 Kgdms 16:13). It makes the recipient one of the Lord’s anointed ones, literally a Christian. At the level of community, it forms the renewed Israel into a royal priesthood.

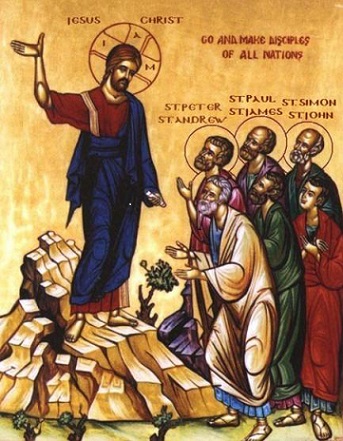

There is not an immediate “shift” from the baptism of St. John to the baptism of Christ at the initiation of Christ’s ministry. St. John the Evangelist makes this clear in his description of the role of baptism in Christ’s earthly ministry (John 4:1-2). To become a disciple of Christ began with receiving baptism, but not baptism by Christ or the baptism of Christ. Rather, the parallel in St. John’s Gospel makes clear that this is the baptism of St. John being administered by Christ’s disciples. Several of Christ’s disciples had previously been disciples of the Forerunner (John 1:35-42). Christ’s baptism is initiated by his death, resurrection, ascension, and enthronement (Matt 28:18-20; Acts 1:4-8). The victory accomplished by Christ is the precondition for the coming of and anointment with the Holy Spirit (John 16:7-15).

In the Acts of the Apostles, St. Luke records an encounter between St. Paul and persons who have received the baptism of St. John but have not heard the gospel of Jesus Christ (Acts 19:1-7). These twelve men have, in fact, not even heard of Jesus or of the Holy Spirit. They were not baptized within the assembly of Christ’s Church. They clearly had not had a baptism which could be described as Christ’s or even as Christian. St. Paul, therefore, identifies Jesus to them as the Messiah whom St. John had proclaimed was coming and in response, they receive Christ’s baptism which they had not yet received, the baptism of the Holy Spirit. St. Paul administers this baptism, not through the application of a second water baptism, but through the laying on of hands. St. Paul acknowledges the reality of St. John’s baptism of repentance (v. 4) but also distinguishes it from Christ’s baptism which is necessary and which fulfills the former. St. Paul does not, in this episode, equate the two and so his actions should not be understood to equate the two.

Historically, the Orthodox Church has, through her hierarchs, the successors of the apostles, chosen at various times and in various places to treat the baptisms performed by various communities outside the church as the baptism of St. John. Likely the most famous historical example of this is St. Basil’s willingness to receive repentant Arians through anointing for the reception of the Spirit without a second water baptism. Such reception of these repentant heretics did not imply any shared faith. An Arian, as much as the twelve men of Acts 19, does not know who Jesus Christ is. It did not imply that the various Arian communities of the fourth century were somehow parallel, much less equally valid, expressions of Christ’s Church. The apostles, as signified by St. Paul in the book of Acts and the interpretations of the authors of the Gospels, acknowledged that within the vast array of ritual washings and anointings practiced by both Jewish and pagan communities, there existed something, as administered by St. John, which constituted ‘a baptism’. This baptism outside of the Church was then treated differently than those other washings and initiation rituals.

Contemporary Orthodox practice, then, is a continuation of this Biblical and traditional understanding. Criteria are set by Orthodox hierarchs by which ‘baptisms’ outside of the Church are distinguished from other rituals, regardless of what those other rituals may be called or how they may be understood by their practitioners and recipients. Those which meet these criteria are then treated by the churches under a hierarch’s supervision as if they were the baptism of St. John, a baptism which required no knowledge of Jesus Christ or the Holy Spirit let alone detailed or correct understanding. Being treated as recipients of St. John’s baptism, these persons then receive the baptism of Jesus Christ, the baptism with the Holy Spirit which comes through anointing with holy chrism. They are thereby made Christians in the proper sense, anointed ones, and incorporated into the royal priesthood of the Church of Jesus Christ.

Would this idea imply that the “12” received baptism on Pentecost as there is no record of all of them being baptized? Of course it just the absence of a direct scripture reference would not be emphatic “proof” that they were not baptized.

Acts 1:4-5 explicitly identifies Pentecost as the baptism of the Holy Spirit administered by Christ to his disciples and apostles over against the water baptism administered by St. John.

I looked up the verses in question. In the OSB, Acts 19:5-6 reads:

” When they heard this, they were baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. And when Paul had laid hands on them, the Holy Spirit came upon them….”

On my first reading, it would seem that baptism in Christ occured first, followed by the laying of hands (Christmation). However you seem to be equating baptism in the Lord Jesus with the laying of the hands and not water baptism? Could you elaborate on the connection you made?

St. Luke’s grammatical construction in these verses isn’t really clear in English. He uses a parallel construction in 4-5 and 5-6. In verse 4, there is an indicative verb, St. Paul ‘said’ followed by a brief summary of his gospel presentation. Verse 5 then begins with a participle, rendered as ‘having heard’. So ‘having heard, they were baptized’. Obviously, what they heard was St. Paul’s gospel presentation, not some additional thing. Their baptism, then, is the direct result of their having heard that presentation. ‘They were baptized’ is likewise an indicative verb. Verse 6 then also begins with a participle, ‘having laid hands’. That participle is not describing another action subsequent to their baptism into the name of the Lord Jesus, but is paralleled and synonymous with what it means that they were baptized into the name of the Lord Jesus. St. Paul laid hands on them. This is then followed by three indicative verbs, the Holy Spirit ‘came’ upon them, they were ‘speaking’ and ‘prophesying’. These three are the direct result of their having been baptized with the Holy Spirit by the laying on of hands.

I know that’s kind of technical, but the TLDR would be, I guess, that if you read the Greek syntax in 5-6 in the same way that we read it in 4-5, it means that the baptism in verse 5 is the laying on of hands in verse 6. One action.

I would also add that any interpretation of St. Luke’s understanding of St. John’s baptism in this chapter has to be commensurate with his understanding of it in Luke 3 and Acts 1:4-5. So if you don’t want to dive into the grammatical shenanigans, these twelve men didn’t receive a second water baptism any more than the disciples and apostles did in Acts 1.

When I read TDLR, I thought ‘what bible version is that?!’

Too Long, Didn’t Read…ah…who knew?! Must be my age 🙂

The ‘shenanigans’ were a bit confusing. I was happy to take your word for it. But your following comment re Acts 1: 4-5 is what clinched it.

I was received into the Church by Chrismation, having been baptized in infancy in the RCC. I was told it was acceptable because a priest baptized in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. I asked no further questions, as I trusted the decisions of our Bishop, Met. Joseph. Had I been given another reason, or if I had been told I needed to be baptized again, it would’ve been fine with me. All I wanted was to be received into the Church. At that point, as a catachumen, I was in no position to question anything.

But this article is the icing on the cake. I mean, as another indication of how we do indeed adhere to the tradition once delivered to the Saints.

Thank you for this post, Father Stephen. Thorough, in depth, and as usual, very instructive.

First time posting!

Before I say anything, I just want to thank you Father for this great blog, it helps greatly in understanding the world of the Old Testament and how it relates to Christ.

This is off topic, but I was wondering what were your thoughts on the Judge Shamgar from Judges 3:31 and Judges 5:6. I’ve heard from secular authors who’ve thought that Shamgar was a Nephilim/demigod due to him being called the Son of Anat (a Canaanite goddess). If this is true it would seem to me to be an incredible story of repentance! It would mean that Shamgar, instead of following the example of his demonic forebears, instead became a Judge of Israel! Or at the very least God used him for such a purpose despite his lineage. Is it at least possible such a thing is true? It would be a great testament to God’s forgiveness and His redemption of evil, and something I would find inspiring. Or is this one of those things that we’ll never know about truly?

It’s not impossible, but it is far, far more likely that this is just a theophoric name which was very common in the ancient world. Many Biblical people have the name of Yahweh incorporated into their names. An obvious one being Elijah, or Eli-yahu. There are also a lot of Biblical people who have theophoric names incorporating the names of foreign gods. Sometimes that’s because these persons are foreigners, like Ben-Hadad, the ‘son of Hadad’. Or the pharaoh Rameses. There are also a lot of Israelites who, unfortunately, have pagan theophoric names. Possibly the most blatant is Amon, the king of Judah descended from David who was nonetheless named after Amun. So, it is unlikely that Shamgar is being portrayed as a Nephilim. But it is likely that he either came from an Israelite family that was syncretistic in its worship or that he was ethnically a Canaanite who was received into the nation of Israel like Caleb.

Thank you for the clarification Father!