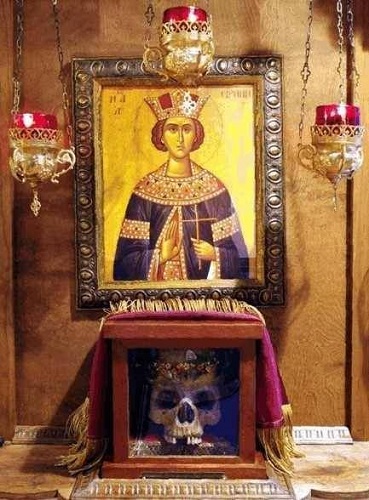

One element of the practice of the Orthodox Church that is particularly troubling to many of those who are outside, particularly in contemporary Western society, is the veneration of relics. This is true even for Christians of Protestant background. In part, the relics of the saints produce either a fascination or an aversion due to the denial of death ubiquitous in our modern cultures. Long gone are the days in which the bodies of departed family members would lie in the home for visitors to pay their respects, then to be solemnly buried with prayers on the property of the family or the church where their graves would be seen and visited continuously by the family and community. Rather, our departed loved ones are whisked away, embalmed to the point where they no longer look human, glimpsed perhaps during a funeral, then interred at some distant place that resembles a park which we might visit on occasion. Against this cultural background, the Orthodox Church and its constant reminders of death and judgment seem morbid. The keeping, displaying, and veneration of the bodily remains of the saints, the members of our family and our community who have gone before us to their rest seems grotesque and horrific.

One element of the practice of the Orthodox Church that is particularly troubling to many of those who are outside, particularly in contemporary Western society, is the veneration of relics. This is true even for Christians of Protestant background. In part, the relics of the saints produce either a fascination or an aversion due to the denial of death ubiquitous in our modern cultures. Long gone are the days in which the bodies of departed family members would lie in the home for visitors to pay their respects, then to be solemnly buried with prayers on the property of the family or the church where their graves would be seen and visited continuously by the family and community. Rather, our departed loved ones are whisked away, embalmed to the point where they no longer look human, glimpsed perhaps during a funeral, then interred at some distant place that resembles a park which we might visit on occasion. Against this cultural background, the Orthodox Church and its constant reminders of death and judgment seem morbid. The keeping, displaying, and veneration of the bodily remains of the saints, the members of our family and our community who have gone before us to their rest seems grotesque and horrific.

This is, of course, far from the Christian understanding of death, its origin, and its purpose. Death entered the world through the sin of Adam, our first parent, and from him passed on to the entire human race. For the angelic being, the Devil, who joined in this rebellion, the death was instant and eternal. The Genesis account describes that this consequence could likewise have befallen the entire human race had we also been immortal (3:22-23). It is for this reason that he clothed humanity in mortal flesh, to allow for repentance and transformation (3:21). While our mortal flesh is capable of transformation through repentance, it is also subject to corruption by virtue of being mortal. This allowed the corruption of sin to fill the whole world through the line of Cain’s cooperation with other rebellious spiritual powers. Human death is therefore not a punishment from God upon human sin but rather so that humans might rather turn and live. It places a limit upon sin, wickedness, and suffering. It is the reign of sin and death which Christ has destroyed by his suffering, death, and resurrection. Humans still die, according to the flesh, but now death has been transformed, it has been, as St. Paul says, swallowed up in Christ’s victory (1 Cor 15:54). Sin, suffering, temptation, corruption, struggle…these things all die while the person created in the image of God comes to life in the Spirit. The same Spirit who raised Christ from the dead (Rom 8:11). St. John of Damascus reminds the faithful of this in the Orthodox funeral services.

This resurrection, the death of the old man corrupt through the lust of the flesh and the rising to a new life of new creation in Christ, is not an instantaneous one at the time of physical death but is rather ongoing (Eph 4:22-24). It begins with death and resurrection with Christ in baptism (Rom 6:4-6). It finds its fullness in the resurrection of the body at the Day of the Lord. The new life begun at baptism is characterized, as St. Paul says, by righteousness and holiness which make us like God (Eph 4:24). Justification, being made righteous, as well as sanctification, being made holy, and even glorification, coming to share by grace in the glory which is Christ’s from eternity, all manifest themselves in the lives of those who follow Christ. Preeminently, they are manifest in the midst of Christ’s assembly, his Church, in the lives of the saints. Just as the corruption of the flesh and mortality affects not only the soul but also the body, so also does the salvation of mankind affect both body and soul. St. Paul carefully distinguishes between the flesh, which is corrupt and perishes, and the body which is raised up to immortality by Christ.

It is this understanding of human persons as wholes finding redemption and transfiguration in Christ, not to mention the creation as a whole, which undergirds the understanding of the human body, in particular, the bodies of those who have fallen asleep, found throughout the Scriptures. The earliest accounts of the disposition of human relics come within the patriarchal narratives of Genesis. At the time of his wife Sarah’s death, Abraham purchased a cave at Machpelah to serve as a family tomb (Gen 23:1-20). This cave would later become his own tomb (25:7-8). In the subsequent generation, both Isaac (35:28-29) and later Rebekah. Within the lifetime of the patriarchs, this place was clearly regarded as sacred, with Joseph having the remains of his father mummified in Egypt so that they could be returned for burial to this site (50:1-13). The place of this tomb is very clearly identified in the Biblical text reflecting it as a pilgrimage site. There is evidence that from at least the 6th century BC, the tomb served as a place of pilgrimage and prayer for subsequent generations of Israelites. Importantly, there is no account in the text of any preceding events or special status for this site that would cause it to be considered holy. Its sanctity derived entirely from the presence there of Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, Leah, and Rachel. The relics of these saints made it a holy place for the ancient Israelites.

This understanding continued throughout the period of ancient Israel with the places of the tombs of the prophets being carefully noted and likewise becoming pilgrimage sites. This knowledge of these places led to the accidental episode related in 2 Kings/4 Kingdoms 13:21, that a body hastily thrown into Elisha’s tomb rose from the dead when it touched his bones. By the Second Temple period, these pilgrimage sites began to be decorated both by patrons and by pilgrims whose prayers had been answered at these sites. Herod the Great had a building constructed for pilgrims at Machpelah which would later become a hub. A Christian basilica was built adjoining and well into the sixth century AD, before the rise of Islam, it was a site of shared pilgrimage by both Christians and Rabbinic Jews. Christ himself makes reference to the decoration of these tombs by the Pharisees (Matt 23:29-32). He does not criticize them for their pilgrimages and prayers at the tombs of the prophets and the graves of the righteous dead. Rather he criticizes their hypocrisy for doing so while being of the same spirit as those who in ancient times had persecuted and murdered the saints and who were about to murder him.

Throughout the period of Ancient Israel and the period of the Second Temple, there was an understanding, carried on within the Orthodox Church, that reverence paid to the bodies of the deceased is received by them. The body is not an object. It was never, by our fathers, cast aside as a husk shed for some greater immaterial life. The body is as much the person as the soul and the two will be restored in the resurrection. As Esau’s descendant Job said, “Would that my words were now written. Would that they were scribed in a book with a reed and metal forever. Would that they were carved in a rock. For I myself know that my redeemer lives. And after a long time on the earth, he will stand. That after my skin is destroyed, this will be, that in my flesh I will see God, whom I will see for myself and my eyes shall see and not another. My heart yearns within me” (Job 19:23-27). And so when Joseph kisses his father’s body during his morning, this is respect and love given to his father (Gen 50:1). Most powerfully, this is the witness of Ss. Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus and the myrrh-bearing women. Though they had watched their life and their hope tortured to death before their eyes, they risked their own lives in order to see to his body. To clean it and prepare it for burial. To mark that place and designate it as holy. To return there for further expressions of love and devotion to Jesus Christ shown through the veneration of his body.

St. Paul’s teaching of the body as the holy place in which salvation takes place, that it is the temple of the Holy Spirit and that it must be kept holy, does not end with the death of that body (1 Cor 6:19-20). When the apostle speaks of the Christian hope, of eschatology, he speaks purely in terms of the resurrection of the body. St. Paul understands that there are a variety of bodies within the creation, both of angels and of men (1 Cor 15:39-41). He understands that our mortal flesh is not identical to the body with which we will be raised (v. 37). Resurrection is not mere resuscitation. Neither, however, is the body of the resurrection completely other than that in which we live this life, just as the creation itself will be transfigured and transformed at the glorious appearance of Christ. These two bodies are called by St. Paul the psychical and the spiritual, but his analogy is to a seed which is buried in the earth and that which grows from it (v. 36-37; 42-44). The care and respect and ritual which attends the burial of a Christian is this planting.

From the very beginning of God possessing a people, from Abraham himself, the bodies of the saints have been treasured and protected, honored and venerated by those faithful people. Their holiness renders the place holy where they rest. To interact with their bodies is to interact with them, they who are not among the dead but among the living (Mark 12:27; Luke 20:38). When our fathers in the faith, for centuries before and after Christ’s incarnation, visited Machpelah they did so to encounter and interact with their living fathers (Mark 12:26; Luke 20:37), and through them the God of our fathers. The Church’s relics, therefore, are her treasured inheritance and prized possession. They are a testimony to the defeat of death by Christ. They are a testimony to the hope of the resurrection of the body and the life of the world to come.

Thank you for explaining this. As an inquirer, soon to be a catechumen, this was very helpful to my understanding. Being raised Protestant and in a family that never spent time taking flowers to relatives graves, this is very different for me.

Lovely article and explanation! Coming from the RC Church into Orthodoxy last Easter, I am happy to know there is veneration of the relics of Saints. They are here with us and such exemplaries for us too.

For many many years relics were venerated in the RC Church and now with everything else, it has been downplayed and watered down along with prayers, rites and worship in general. I thank God every day for the Orthodox Church where all has been kept in tact properly and from the beginning. The Orthodox Church is a no-nonsense Church…..

God bless & Happy Thanksgiving from Canada!

Thank you for this! So helpful!

Thank you Fr De Young.

This post is as usual very helpful and interesting.

As an evangelical, I’m afraid of all that can be identified as idolatry and necromancy.

Like the posts related to icons, prayers to Theotokos, angels, saints…I find this one very enlightening, rich but I need some time to digest

Once again, thank you very much. Your blog, podcasts and facebook page are a blessing for me.

May God bless you richly.