Contrary to modern misperception, every element of the Torah, the law of God, is still in force and relevant to the life of the Christian faithful today. There can be no clearer or more authoritative testimony to this fact than the word of Christ himself (eg. Matt 5:17-19). Despite its contemporary caricature, the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15 represents a strict reading and application of the Torah to the situation of Gentiles entering into the assembly, the Church, of Christ. St. Paul fiercely defended himself against the charge of seeking to abolish the Torah or promote its violation throughout his missionary journeys as described in the Acts of the Apostles and in his own epistles (eg. Acts 21:20-21; Rom 3:31). Over against these clear statements of the New Testament authors, there is a general impression that at least some of the commandments of the old covenant have been set aside. The greatest source of this impression comes from the language used in the controversy over circumcision.

Contrary to modern misperception, every element of the Torah, the law of God, is still in force and relevant to the life of the Christian faithful today. There can be no clearer or more authoritative testimony to this fact than the word of Christ himself (eg. Matt 5:17-19). Despite its contemporary caricature, the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15 represents a strict reading and application of the Torah to the situation of Gentiles entering into the assembly, the Church, of Christ. St. Paul fiercely defended himself against the charge of seeking to abolish the Torah or promote its violation throughout his missionary journeys as described in the Acts of the Apostles and in his own epistles (eg. Acts 21:20-21; Rom 3:31). Over against these clear statements of the New Testament authors, there is a general impression that at least some of the commandments of the old covenant have been set aside. The greatest source of this impression comes from the language used in the controversy over circumcision.

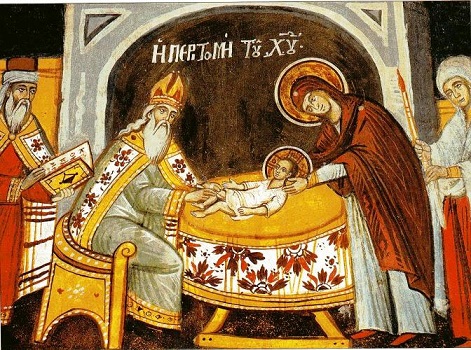

Circumcision occupied a position of centrality in the old covenant equivalent to Baptism in the new. It was the marker of membership in the people of God. It’s ritual establishment and significance preceded the giving of the old covenant to Moses by centuries. It constituted the people of Israel not as a national entity but as a family, the family of God. Moses’ failure to follow this most basic of Yahweh’s commandments nearly led to his own death (Ex 4:24-26) and resulted in his loss of the priesthood to Aaron and his line. It was nearly inconceivable, then, to the greater body of the faithful in Judea, that someone could come to be a member of the people of God and partake of Christ as the new Passover without first being circumcised (Ex 12:48). St. Paul argues fiercely against the necessity of circumcision for those who were coming from the nations into the people of God. This argument is not only the major focus of his Epistle to the Galatians, but it also sets the stage for the council of Acts 15. While there seems to be a clear connection in function between Baptism and circumcision, surely the significance of circumcision, along with its necessity, has been set aside in the new covenant? A surface reading would seem to indicate so. While the intuitive connection between Baptism and circumcision is a correct instinct and important to the understanding of the propriety of infant Baptism, to merely say that Baptism has replaced circumcision is to move too quickly and pass over the ways in which St. Paul, above all New Testament writers, continues to utilize the language and commandments regarding circumcision.

Circumcision as a sign was first given to Abraham (Gen 17:1-14). In the wake of the rebellion at Babel, Yahweh had dispersed the nations, assigning them to the governance of angelic beings. He is going to use a nation that will serve collectively as priests for all of the nations of the world until that nation brings forth Christ as the culmination of its ministry. Rather than choosing one of the 70 nations which already existed to favor over the others, Yahweh creates one which previously did not exist. He creates it from one man of Ur named Abram. At the giving of his initial covenant with Abram, he changes his name to Abraham, promising to make him the father of many nations, to bless all the nations of the world through him and his descendant. The way in which someone was made a part of this people was through circumcision. Circumcision not only or even primarily of one’s self, but of all the males of one’s household, including even slaves. In a deliberate wordplay, anyone not circumcised was cut off from this covenant and the people whom it created.

The covenant, as St. Paul would later strongly argue, was therefore not based on biological ethnic descent. Rather, it was based on faithfulness in keeping the commandment of circumcision and “walking before the Lord in righteousness” (Gen 17:1). For St. Paul, this righteousness is a function of this faithfulness. The faithful one is the one reckoned to be righteous. Righteousness comes by faithfulness. It was therefore always those who were faithful, like Abraham, who were his children (Gal 3:7). Abram of Ur was a Chaldean (Gen 11:28, 31). This anachronistic term is used to describe him in order to connect him to Babylon, the place of the tower of Babel. Abram is called out of Babylon, the capital of the world in all of its negative connotations, to become the foundation of a new nation and so circumcision enacts him cutting himself off from the world, under the sway of the power of darkness, from which he came. He is given a new name, Abraham, and this is done on the eighth day for his progeny to communicate that he is now a new creation, as are they (Gal 6:15).

This cutting off takes place in relation to the genitals because it is not primarily an individual act of devotion or a pledge made by an individual. Rather, it is constitutive of community and therefore involves not only the male but his spouse and his progeny. The broader community of Israel was a family, the family of God. It began with the family of Abraham and was always composed of tribes and clans, family units. These units always included strong elements of adoption, of incorporation of outsiders into family and clan. Newcomers, both by birth and adoption, shared in this cutting off as the ritual means of integration. Women and female children were integrated through their family bonds to the circumcised male who was the head of the household as only males were circumcised. The circumcised male cut the family unit off from the world, setting apart and therefore definitionally making it holy. It was the responsibility of the women of the household to maintain the purity and holiness of the household in both a physical and spiritual sense while it was the responsibility of the males who ventured out into the world to not yield to its impurity and bring sin and impurity back into the home. The circumcision of the flesh was to embody the circumcision of the heart, which needed to be cut off from the world and its desires and temptations (Deut 10:12-17; 30:6; Jer 4:4; 9:26).

St. Paul reveals that every element of circumcision finds its fulfillment in Christ. This does not mean that it is done away with. Rather, every element is filled to overflowing in such a way that Christ represents the truth and reality which stood behind the shadow of the ordinance of circumcision (Col 2:17). To return to the circumcision of the flesh, then, is to forsake reality and fulness for image and shadow and remove one’s self from Christ, if not outright deny that Jesus, the Christ, has come as that fulness. Basic to St. Paul’s understanding of the crucifixion of Christ is that it represents an inversion of the curse of the Torah (Gal 3:13). In his suffering and death, Christ was cut off from among the people. Christ’s receipt of the curse, however, did not cut him off from life. Rather, being God, his cutting off was the final cutting off of the world and its prince, the dark powers and the passions and wickedness which had infested the creation, from God. It is, therefore, the world as a system, as represented by its capital, Babylon, that is judged and dies (Rev 17:1-18:8). The person then, who is in Christ has been cut off from the world and the world from him (Gal 6:14). That person is a new creation (2 Cor 5:17).

Participation in Christ’s death and resurrection and the reality of this cutting off and new creation takes place in the mystery of Baptism. To be baptized is to be baptized into Christ and thereby to put on Christ (Gal 3:27). To be baptized into Christ is to be integrated into the family of God (v. 26). It is to leave behind whatever characterized life in the world and its system of relationships to become a part of a new people created by God (v. 28). That new people is new to the one baptized but is the same family, the same people, created by Yahweh through Abraham to exist eternally (v. 29). Before his death, his cutting off, Christ sanctified himself (John 17:19). Those who are baptized into Christ are set apart and made holy by him through participation in his family (Heb 2:11). St. Paul can, therefore, say that we have all been circumcised with Christ’s circumcision in baptism (Col 2:8-12). Christ has therefore established the spiritual and material holiness of his house and his household members. It is the responsibility of the Church to protect and maintain that holiness because she is his bride. It is in precisely this sense that the Church is spoken of in feminine terms.

St. Paul applies this theological understanding of the deep connections between circumcision and Baptism found in Christ’s fulfillment practically in ways that stem directly from the understanding of circumcision. In addressing faithful Christians married to non-Christians, he applies the principle that the circumcised father sanctifies, renders holy, mother and children (1 Cor 7:12-16). He applies it, however, in both directions. A faithful wife renders husband and children holy in the same sense as a believing husband would. This is because the holiness which comes to believing families is not the holiness of a human man who has set himself apart in the flesh or even in his heart. It is the holiness of Christ himself in whom the faithful, baptized Christian participates whether male or female. That this still holds true reveals that Baptism, like circumcision before it, was never an individual act or pledge. Rather, it has always been, from the very beginning, a communal act of family, clan, tribe, and nation; the new nation which is called by Christ’s name, the Church. The Church integrates new members, both by birth and from outside, through the ritual means of Baptism. This renders them co-heirs of the promises with Christ (Rom 8:17), members of the family of God, a people holy and set apart from the world which is perishing (1 Pet 3:20-21), and a new creation in Christ. Circumcision, in the Church, is not abolished but fulfilled.

Thank you for this great article, Father! In your article on Acts 15 you pointed out that the Council of Jerusalem applied the elements of the Law of Moses to Gentile Christians that were traditionally binding on Gentiles living in Israel (bans on idolatry, sexual immorality, eating blood). If those are the only Mosaic commandments which traditionally bound Gentiles living among Israel, to what extent do the other commandments still apply today? For example, in another article you pointed out that the laws against uncleanness are still in force but have been altered since Christ made all animals clean; how does that relate to the lives of non-Jewish Christians since the Law of Moses didn’t set dietary laws for Gentiles anyway?

It’s not so much that the commandments have been altered as, as you say, the material world having been cleansed by Christ’s atoning sacrifice. So the commandments regarding clean and unclean still apply, but they apply to moral uncleanness. Ceremonial uncleanness was the embodiment of moral uncleanness in the first place. So dietary laws now take the form of our fasting disciplines. These are not based on giving up something bad or evil, but rather giving up material, temporary goods in exchange for greater, eternal goods. This shift in our relationship with the world from the avoidance of the unclean that was outside of the dominion of God in the world to asceticism is the theme of most of Christ’s preaching in the Synoptic Gospels.

I think what I’m trying to ask is: if dietary laws are still in force upon us, in the form of our fasting disciplines, why did the council in Acts 15 only impose those parts of the Law of Moses that were always in force on Gentiles living among Israel? Wouldn’t that mean that the dietary laws, in whatever form they take after Christ’s atoning sacrifice, still only apply to Jewish Christians?

The commandments pointed to in Acts 15 are listed because, based on the Holiness Code in Leviticus, they are of a different order. They are sins which pollute the earth. Meaning, they are corruptions of the created order itself and are universal for this age in space and time. There is no change in application possible for these commandments. The rest of the commandments were given in their Torah form to Israel based on Israel having the role of priests in relation to the other nations of the world. In the same way that priests in Israel (and the Church) are required to follow more stringent patterns of holiness than the laity, so also with Israel compared to the nations. The Church vis a vis the world has a renewed role, in Christ, and so while all of those commandments still apply to the life of the Church they apply in ways fulfilled and transformed by Christ. This piece is an example of what that means, in the transformation of the commandments regarding circumcision in how they continue to apply in the life of the Church. Acts 15 is not saying that the commandments regarding circumcision are now voided or only apply to Jewish Christians. It is saying that unlike the commandments regarding idolatry and sexual immorality, they apply differently such that there is no reason for a Baptized Gentile who has received the Holy Spirit to be circumcised in the flesh. To say that this is still required is to fundamentally misunderstand Christ.

Thank you, Father!

Father Stephen,

Thank you for unpacking and unfolding, from the beginning, the role of circumcision and it fulfillment in Baptism into Christ.

I don’t know, but its like sitting down to a meal you’ve never had before. Your expectations are far exceeded. And you leave full to the brim. You’ve got to digest this stuff! But it is so good. So fulfilling!

I noted something you said: “In his suffering and death, Christ was cut off from among the people. Christ’s receipt of the curse, however, did not cut him off from life. Rather, being God, his cutting off was the final cutting off of the world and its prince…”

Is this what Daniel 9:26 is referring to? “And after the sixty-two weeks Messiah shall be cut off, but not for Himself; And the people of the prince who is to come Shall destroy the city and the sanctuary. The end of it shall be with a flood, And till the end of the war desolations are determined.”

Does “but not for Himself” refer to “the receipt of the curse did not cut [Christ] off from life”. Then the prophesy goes on to say “the end shall be with a flood”… is that St Peter’s analogy in 1 Peter 3:20-21? I think I need a little more unpacking! Somewhere in all this, I have trouble distinguishing the ‘beginning of the end’ in Christ’s first coming and its culmination in His second coming.

Again, thanks so very much.

What I especially like about this article is the delineation of the role of men and women, as the woman is to keep the home pure, and the man is to fight off the temptations of the world and not bring it home.

Thank you, Fr Stephen. These commentaries are very helpful.