Debates surrounding atonement theology over the last several decades have centered on two terms, propitiation and expiation. Both of these terms describe the function of particular sacrificial rituals. There is not, of necessity, a conflict between the core meanings of these two terms. They have come, however, to be emblematic of entire theological positions regarding the atoning sacrifice of Christ. Clearing away the accumulated theological baggage from these terms, however, allows them to highlight two important elements of the sacrificial system described in the Hebrew scriptures which will, in turn, reveal elements of the Gospels’ portrayal of Christ’s atoning death. Rather than summarizing two incompatible views or options or theories regarding “how atonement works,” these elements, along with others, convey ways of speaking and understanding sacrifice which together produce a rich, full-orbed understanding of what our Lord Jesus Christ has done on our behalf.

Debates surrounding atonement theology over the last several decades have centered on two terms, propitiation and expiation. Both of these terms describe the function of particular sacrificial rituals. There is not, of necessity, a conflict between the core meanings of these two terms. They have come, however, to be emblematic of entire theological positions regarding the atoning sacrifice of Christ. Clearing away the accumulated theological baggage from these terms, however, allows them to highlight two important elements of the sacrificial system described in the Hebrew scriptures which will, in turn, reveal elements of the Gospels’ portrayal of Christ’s atoning death. Rather than summarizing two incompatible views or options or theories regarding “how atonement works,” these elements, along with others, convey ways of speaking and understanding sacrifice which together produce a rich, full-orbed understanding of what our Lord Jesus Christ has done on our behalf.

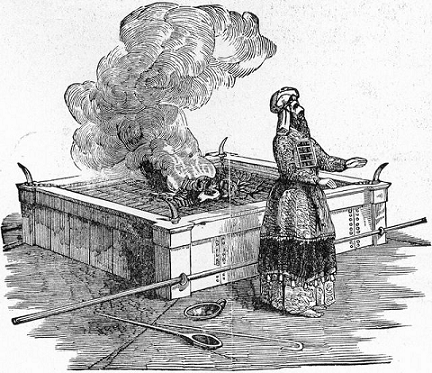

Both propitiation and expiation in the scriptures view sin through an ontological lens. It is a thing which exists in the form of a taint, an impurity, similar to a deadly disease. Like a deadly infection, if left uncontrolled it will not only bring death, but will spread throughout the camp in the wilderness, the nation, and the world. While this is true of sin generally, the presence of Yahweh himself in the midst of his people in the tabernacle and later temple elevates this danger. The Day of Atonement ritual, for example, is instituted in Leviticus in response to the fate of Nadab and Abihu, the sons of Aaron who entered into the tabernacle unworthily in their drunken sinfulness and were consumed by the fire of God’s holiness (Lev 10:1-2; 16:1-2).

In fact, the entirety of the commandments of the Torah is a means of dealing with sin and related contamination in order to allow Yahweh to remain in the midst of his people. The failure of Israel and then Judah to follow it results in the departure of Yahweh from the temple and the removal from the people from Yahweh’s land. The internecine debates within Second Temple Judaism primarily surround what must be done vis a vis the Torah and the way of life of the people to correct the resulting situation. The Christian proclamation within this debate is that Yahweh has visited his people in the person of Jesus Christ. Christ has fulfilled the commandments of the Torah (in filling them to overflowing) and accomplished what they, of themselves, could not. While the Torah prescribed a sort of sin management system, Christ has dealt with sin once and for all, so that the commandments of the Torah now function, empowered by the Holy Spirit, to cure the disease of sin and transform human persons into sons of God.

Within this overall system, sacrificial ritual occupies a central place and it is within the sacrificial system that we see principles of propitiation and expiation. Expiation, as a term related to atonement, refers to the removal of sin. The danger to the community posed by sin and its resulting corruption is remedied by the removal of sin from those so contaminated and ultimately its removal from the entire community. It has become popular, due to baggage loaded into the other term, propitiation, for some to argue for expiation as an alternative, meaning that expiation represents the entirety of the function of sacrifice. The direct connection of expiation to sacrificial ritual, however, is tenuous at best. It is not uncommon, for example, for people, even scholars, to shorthand sacrificial practice by saying that before the killing of an animal the priest would place the sins of the offerer, or the people as a whole, upon that animal and then kill it. Unfortunately, this is something which occurs nowhere in the sacrificial system as outlined in the Torah, nor anywhere in the pagan sacrificial rituals of the ancient world for that matter.

The one ritual in which such a thing occurs is within the ritual of the Day of Atonement (as first described in Leviticus 16). Within this ritual, two goats are set apart and lots are cast (v. 7-8). One of these goats is then taken and the high priest pronounces the sins of the people over it (v. 20-22). This goat is not the goat “for Yahweh.” This goat is not sacrificed. In fact, this goat cannot be sacrificed because, bearing the sins of the people upon it, it is now unclean and unfit to be presented as an offering. The goat is so unclean, in fact, that the one who leads it out into the wilderness is himself made unclean by contact with it (v. 26). The goat is sent into the wilderness, the region still controlled by evil spiritual powers as embodied in Azazel, such that sin is returned to the evil spiritual powers who were responsible for its production. This represents the primary enactment of the principle of expiation in Israel’s ritual life, though the principle is found throughout the Hebrew scriptures (eg. Ps 103:12). The New Testament authors see this element of atonement fulfilled in Christ as he bears the sins of the people and is driven outside of the city to die the death of an accursed criminal (as in Matt 27:27-44; Rom 8:3-4; Heb 13:12-13).

A much more widespread concept which falls under the category of expiation is that of purification, purgation, and washing from sin often associated with blood. This is not so much expiation enacted within sacrificial ritual as it is a result of sprinkling or smearing of blood which wipes away sin. This idea is at the core of the terms translated “atonement” in Hebrew itself. As part of the sacrificial offering of the other goat, the goat “for Yahweh,” its blood is drained and is used to purify the sanctuary, the altar, and the rest of the accouterment of the tabernacle (Lev 16:15-19). The annual Day of Atonement ritual takes place in addition to the regular cycle of sin and guilt offerings that take place throughout that year and has, as its key purpose, the cleansing of the sanctuary itself. While sin has been managed through these other offerings, it has left a resulting taint and corruption in the camp which is especially dangerous in the place in which Yahweh himself resides and so this must be purified. Once again, handling this blood which absorbs and removes sin renders the high priest himself contaminated and so he must purify himself before he goes on to offer the rest of the animal to Yahweh (v. 23-24). This element of washing and purification from sin is found throughout the Hebrew scriptures (eg. Ps 51:2, 7), forms much of the basis of the understanding of baptism beginning with that of St. John the Forerunner, and is applied to the operation of the blood of Christ by the New Testament authors (eg. Eph 1:7; Col 1:20; Heb 10:3-4, 19-22; 1 Pet 1:18-19; 1 John 1:7; Rev 1:5).

The term propitiation has been freighted with a great amount of theological baggage. Specifically, it has been used as a sort of synecdoche for the systematic view of penal substitutionary atonement. Many now take it to refer to the appeasement of God’s wrath through the punishment of a substitute for the sins of a person or people. Attempting to import this conceptual whole into the sacrificial system as established in the Torah is simply impossible. Much of the sacrificial does not even involve the killing of an animal. Offerings of the sacrificial system are always food. There is a sacrificial meal involved in which the offerer and those bringing the offering eat and/or drink a portion of the meal while a significant portion, the best, is offered to Yahweh. Animals which are going to be a portion of these offerings and meals are, of course, killed as they would be before being a part of any meal. But there is no attention paid to the mode of their killing by the text of the Torah. Precise details are laid out regarding how they are to be butchered and what is to be done with the various parts of the animal and the cuts of meat. But their killing is not even ritualized. This likewise means that some sort of punishment or suffering on the part of the sacrificial animal is no part of the ritual. Even in the case of whole burnt offerings in which the entirety of the animal is burned and thereby given to Yahweh, it is not immolated alive but is killed first, unceremonially.

Propitiation itself, however, has a much simpler meaning. Literally, of course, it means to render someone propitious, meaning favorably disposed. At its most simple level, it refers to an offering which is pleasing to God. Unlike pagan deities, Yahweh does not require care and sustenance in the form of food from human worshippers. There are, however, significant instances of his sharing of a meal in a literal sense (eg. Gen 18:4-8; Ex 24:9-11; and of course numerous meals shared by Christ in the Gospels). The more common language used in the scriptures for God’s appreciation for his portion of sacrificial meals is that these sacrifices are a pleasing aroma (as in Gen 8:21; Lev 1:9, 13; 2:2; 23:18). This same language is applied to the sacrifice of Christ in the New Testament (as in Eph 5:2 and the Father’s statement that in Christ he is “well pleased”). In the Greek translation of Numbers 10:10, the language of a memorial is used to describe the sin offering as its smoke rises to Yahweh. This language is applied to prayers and almsgiving elsewhere in the scriptures (Ps 141:2; Acts 10:4; Rev 5:8). The party who is being propitiated through atonement may be wrathful toward the one who makes the offering (as, for example, Jacob assumes in Gen 32:21 regarding Esau), but this is not necessitated by the language of propitiation as such.

Understanding the wrath of God as a function of his presence, of his justice and holiness, there is another element of propitiation which is directly relevant to wrath. This is the protective function which sacrificial blood and incense offerings serve in relation to Yahweh’s presence. Part of the Day of Atonement ritual is specifically oriented toward allowing Aaron to enter the most holy place without dying as had his sons (Lev 16:11-14). An obscuring cloud of smoke, as well as the blood of a bull to wipe away the sins of himself and his priestly family, are required because, on that day, Yahweh himself would appear, would make himself present, in that place (v. 2). The blood of the sacrificial lamb, which was utilized as a meal, at the Passover served a similar protective role (Ex 12:21-23). This is not protection from a loving God. Rather, it is a means provided by that loving God to allow sinful human persons to abide in the presence of his holiness. This same sort of protection language is utilized regarding the blood of Christ (eg. Rom 3:24-25; 5:9; Eph 2:13; Heb 10:19-22; Rev 12:11).

Propitiation and expiation, themselves being seen from a variety of perspectives, are inseparable elements of what atonement means in the scriptures. They, along with other elements already and still to be discussed, form the cohesive understanding of Christ’s own sacrifice on the cross. These are not abstract principles, theological rationales or arguments. They are not constructed ideas used to explain mechanisms by which salvation takes place. Rather, they are highlighted moments of experiential reality. The core of Israelite, Judahite, and Judean religion was sacrificial ritual which brought about states of being and consciousness in its participants and the world itself. Ancient people, the first Christians understood the self-offering death of Christ in terms of this lived experience. This post and the others in the present series seek to reestablish access to this experience of God through delineating the shape of that experience for our fathers in the faith.

Thankyou! To keep my comment simple, I always think of God as accepting what we offer to Him as Atonement – could be in a fast, could be in our suffering, or giving up something so another in need can have it etc….

I say this because I think our offerings if done with the right intention and not parading it around, is what God is looking at. It is between me and Him in other words. He will accept our offering as an Atonement or not depending on what lesson we need to learn out of the sin and Atonement.

The Atonement could be overnight; it could also take years!

God bless…..

I’m with you so far, Father! Thank you!

In Rm 3:25 ( NKJ) “whom God set forth as a propitiation by His blood…”, there is a footnote that translates propitiation as “mercy seat”. I also see that both words are a translation of the word “hilasterion”.

Would you say the term “mercy seat” is an adequate translation? I ask because I remember well as a Protestant that the sprinkling of blood on the mercy seat was understood as part of PSA . It was a significant part of that teaching. I find it interesting that I have not come across that term in Orthodox writings.

“Mercy seat” is a translation that came into English Bibles early on that refers to the lid of the Ark of the Covenant. More recent translations tend toward ‘atonement cover.’ The cover of the ark with its cherubim is one of the objects on which blood was smeared to purify it in the most holy place on the Day of Atonement. It is the footstool of the throne of God and so represents his presence. It is the place of atonement, and so is referred to with the same noun.

Where “mercy seat” came from is a long story involving rabbinic Judaism’s reinterpretation of Daniel 10 in a sort of modalistic reading. So it came in through the side door to the English Bible through the rabbinical Hebrew text. That’s why you don’t find it much in the Orthodox tradition.

Interesting, Father. Thank you.

I have heard it said that the Theotokos is the “mercy seat”. What would it mean for the Theotokos to be the “atonement cover”?

This is connected to the imagery of the Theotokos as the new Ark of the Covenant, to which the atonement cover was the lid. We see this iconographically in that Christ is depicted in the apse of most Orthodox churches enthroned on the Theotokos’ lap. It is drawn directly from the scriptures. St. Elizabeth’s protest, “Who am I that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” (Lk 1;43) closely parallels David’s, “How can the Ark of Yahweh come to me?” (2 Sam 6:9) being just one example.

Thank you Father for this explanation of expiation & propitiation. This is the explanation of these terms that I needed to disentangle them from penal views of atonement.

What do we suppose are the long term effects of emphasizing penal substitutionary atonement at the expense of the ontological aspects of Christ’s atonement — on the individual personal life? I am tempted to list every negative outcome from my (Reformed) background. But that’s not fair and does not leave a reasoned trail that can be traced back. For starters, I think PSA leads to a heavy forensic emphasis that can lead to superficial moralism. No doubt there is also an impact on matters that are paramount to Christ, like love and mercy and humility.

Thank you, Father. This is the first time I’ve come across a simple, biblically grounded, theory-free definition of “propriation”. The term has always eluded me, despite years of being (superficially) familiar with it and reading about it. In my journey to the Orthodox church, a book by the priest who baptized me made the argument that the proper Orthodox understanding of atonement begins and ends with the expiation (or cleansing/healing) of sin, or of being made whole, in Christ, and of restoring the divine image in which we were originally made — and has nothing to do with propritiation — period. In his presentation of the issue, he unwittingly seems to have fallen prey to the same false, theory-laden association of propritiation with penal substitutionary atonement, or with the idea that propritiation essentially involves appeasing God’s wrath, when in fact, as you show here, there is no need to view the term in this light at all. The book, mind you, was a very good one, and it helped me to get away from the notion of penal substitution, but I now see that it fell somewhat short in its caricatured treatment of propritiation. Your post here does a great job of reclaiming a proper understanding of what is actually going on in “appeasing” a loving and yet fearsome God (rather than his supposed penally motivated wrath).

Thank you for your article, Father. I am not Orthodox, but I am inquiring. Please help me understand: So when Nahab and Abihu didn’t do what was necessary to allow themselves, as sinful human beings, to stand in the unmitigated presence of loving Yahweh, did Yahweh suddenly turn wrathful/angry on them? Or was it that their mortal, sinful bodies could not bear His loving presence? To me, even after reading your article, it still sounds like the sacrificial system functioned, in one important sense, in order to protect people from a very dangerous (wrathful) God who strikes people dead if something isn’t killed beforehand. Hence, sacrifice becomes necessary to appease (perhaps figuratively speaking) Yahweh’s wrath that, granted, He doesn’t want us to experience when in His presence, but–and almost as if His wrath is beyond His own loving control and therefore He has to hide Himself from us lest He kills everyone–which we will undoubtedly experience to our severe detriment if we don’t meet the prescribed requirements. You can see I got my drawers all in a bunch here haha. What am I missing?

Well, we’re not talking about people being tortured by God’s love, but his holiness and righteousness. When Isaiah comes into the presence of God in his prophetic call, there is no intimation that God is angry with him. Rather, Isaiah experiences coming undone because of his sin and the sins of his people (Is 6:5). He has to be purified by fire from the altar in order to be able to stand there.

The core distinction though is this: who changes in atonement, me or God? One approach says that God is angry at me over my guilt for a multitude of sins. Atonement offerings then cause him to cease be angry and to love me instead. He wants to love me, but a standard of justice which he must obey will not allow him to love or bless me because of sin or leave any sin unpunished. Therefore, he has to punish someone or something else for my sins, at which point he is allowed to love and bless me and to be at peace with me. This is the Western atonement construct as it bloomed at the time of the Protestant Reformation. Unfortunately, I just don’t find it in scripture. But in summary, in this view, atonement changes God, vis a vis his attitude toward me.

What I am attempting to do in this series is to draw out the actual Biblical moments that make up the concept of atonement in the scriptures which, taken as a whole, are about the way in which atonement changes us. God loves us from beginning to end, but we by our sin reject that love and remove ourselves from God’s blessings. Atonement transforms us so that we can now enter into God’s presence and come to know him ever more deeply.

Thank you for your response. I’m looking forward to the rest of your series, truly. But if I may ask one more question (or two): What is the relationship between God’s love and holiness? And somewhat related to this, isn’t there an Orthodox theologian and saint that said something along the lines that when Christ returns, to those that love Him His love will be bliss, but to those that hate Him His love will be (perpetual, torturous) wrath?

Perhaps, I’m getting off topic here? I guess the problem I’m having is that there seems to be, at least in my own limited understanding, two distinct pictures of God to choose from, either a) God’s love and wrath are ontologically (not experientially ) indistinguishable, or b) God’s love and wrath are at odds within Himself. Is there a third? Or, is it possible that both are approximate truths of the reality of God’s presence in our lives, depending on how careful we talk about them? I mean to say, could PSA be true on some metaphorical level? Not that Christ satiated a God bent on torturing sinners, but rather, that Christ’s death and resurrection secured a path for sinners to experience God’s presence as it truly is, as love and bliss and not torturous wrath. If the latter is (more) true, can’t we then say that in some sense Jesus’s atoning sacrifice satisfied the conditions needed for us to not experience God’s eternal wrath, and instead experience His eternal love and care, as long as we embrace Christ? Or, perhaps PSA doesn’t allow for such nuance? Sorry, that turned into much more than two questions.

God’s love and his holiness are two divine energies. In modern Orthodox rhetoric, a certain sloppiness has crept in, I believe as an overreaction against penal substitutionary atonement, which tries to make the torments of hell the result of God’s unrequited love. That picture of God is, if they followed it through, more monstrous and strange than anything proposed in the West. The Fathers use the analogy of the sun, which shines on some clay and softens it, other clay and hardens it. The point of the analogy is that the difference is in human persons, not in God’s love for them or treatment of them. The overarching narrative of the scriptures is that man was created and brought into God’s presence, Paradise, to share his life. By his disobedience, he created a problem. Had God allowed him to remain in Paradise, he would have become like the demons, irredeemably confirmed in their evil eternally. So man was expelled from Paradise into this present world and given mortal flesh in order to allow for repentance and transformation so that in Christ, human persons could be made ready to again enter God’s presence on the last day. How a human person chooses to use this present life, for repentance or merely to continue in rebellion, is up to each person. The scriptures are clear that God loves us and desires that none of us should perish, but that we all would repent and share his life with him for eternity. But coming again into the presence of God at our judgment (because it is our judgment) will either purify us like gold in a furnace or destroy us like so much dross depending on what we have done in our life.

Your proposed redefining of PSA may be a more palatable view, but is so removed from PSA proper that it sort of makes the term useless in discussion. If we keep a term but use it in a completely different way, it does the opposite of communicating. Better to just let go of the term.

One of the chronic problems with the theology of the Reformation is anthropomorphism. God loves and hates and is angry in a sense parallel to human persons. The understanding of God’s will is like a fallen human decision making will. I can’t count the number of Calvinist scholars who just outright reject the Sixth Ecumenical Council because they haven’t worked through the concept of a natural will. God plans things and then executes those plans the way a human does. When we start mistaking analogies and metaphors aimed at making the ineffable understandable by humans for direct statements of propositional truth, theology gets radically skewed.

Thank you, Father Stephen, for your insight and for taking the time to respond to me. This has helped. Have you read Fr. Patrick Reardon’s “Reclaiming the Atonement”? Would you recommend it, or any other book on this topic?

I am wondering if when we are drawing closer to God’s presence, that we also become aware of our own sinfulness and this brings about the wrath of God – not that He is standing there waiting, angry, to judge and condemn with His wrath. It is we ourselves who are not worthy to be in His presence, but also that we are humbled in knowing so. Perhaps it is better understood as the wrath of our own sins that come upon us before we are cleansed and purified to be in God’s presence. (?)

In the Jubilee Bible, this word is consistently translated as “reconciliation” in the NT. This seems to be an improvement over picking expiation, propitiation, or atoning sacrifice.

Here are two examples:

Romans 3

1But now, without the law, the righteousness of God has been manifested, being witnessed by the law and the prophets:

22the righteousness, that is, of God by the faith of Jesus, the Christ, for all and upon all those that believe in him, for there is no difference;

23for all have sinned and are made destitute of the glory of God,

24 being justified freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Jesus, the Christ,

25whom God purposed for reconciliation through faith in his blood for the manifestation of his righteousness, for the remission of sins that are past, by the patience of God,

26manifesting in this time his righteousness that he only be the just one and the justifier of him that is of the faith of Jesus.

And 1 John 2

My little children, I write these things unto you, that ye sin not; and if anyone has sinned, we have an Advocate before the Father, Jesus, the righteous Christ;

2and he is the reconciliation for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world.

Do you think, Father, that this is a better rendering or not?

Thank you.

“Reconciliation” works in terms of conveying an important level of meaning. What you lose, though, is the connection to the Day of Atonement and other instances of Atonement in the OT. The Greek ‘hilasterion’ in the NT carries with it the imagery of the two goats, purification, etc. Reconciliation doesn’t necessarily carry that. So I think the word ‘atonement’ still serves. Especially since it is a word invented for the English Bible with no real outside preceding meaning.