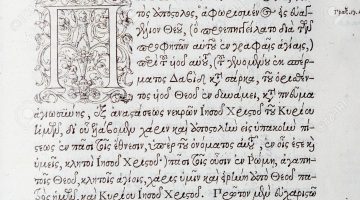

In many ways, the content of the New Testament, and even its text, are a much more settled issue than that of the Old Testament, as previously discussed. That said, there is still a great deal of debate about which text of the New Testament, in its details, holds canonical authority. This is due to an embarrassment of riches with regard to the New Testament text, for which we have nearly 6,000 manuscripts. A manuscript, properly speaking, is a hand-written copy of a text. Our extant manuscripts of the New Testament stretch from the early part of the second century to the beginning of the 20th century, at which point many churches in Greece were still reading the epistles and gospels from manuscripts, as the Turks had prevented their access to a printing press. This number is particularly amazing when compared to the text of other books from antiquity. For example, the critical edition of Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens contains photographs of all of the existing Greek manuscripts; a total of four. Further, none of these four is complete, and even all four collated together does not include the entirety of the text.

In many ways, the content of the New Testament, and even its text, are a much more settled issue than that of the Old Testament, as previously discussed. That said, there is still a great deal of debate about which text of the New Testament, in its details, holds canonical authority. This is due to an embarrassment of riches with regard to the New Testament text, for which we have nearly 6,000 manuscripts. A manuscript, properly speaking, is a hand-written copy of a text. Our extant manuscripts of the New Testament stretch from the early part of the second century to the beginning of the 20th century, at which point many churches in Greece were still reading the epistles and gospels from manuscripts, as the Turks had prevented their access to a printing press. This number is particularly amazing when compared to the text of other books from antiquity. For example, the critical edition of Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens contains photographs of all of the existing Greek manuscripts; a total of four. Further, none of these four is complete, and even all four collated together does not include the entirety of the text.

With the richness of textual evidence we still possess for the New Testament, we have the opposite difficulty. We very often have multiple versions of a single verse. Further, sections of text both large and small are found in some manuscripts and not others. Famous texts in this category include the Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53-8:11), the Comma Johanneum (I John 5:7-8), and Christ’s prayer of forgiveness from the cross (Luke 23:34). These texts, and many others that are well known and even beloved by Christians do not appear in the earliest manuscripts, and seem to appear at certain periods of time in particular places. Some of them, such as the Pericope Adulterae, when they first appear, appear in different places, in this case, in the Gospel of Luke rather than John. In some cases, such as the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, there are even multiple versions of a book, of significantly different length.

A common response to this in the West has been to attempt to establish an authoritative text by giving to one particular edition of the New Testament preeminence over all others. In response to attempts within the Protestant Reformation to get behind the then current state of the Latin Vulgate text to the Greek, the Roman Catholic church of the 16th century made the Latin Vulgate, not in general but as it existed at that time, the authoritative text. Meanwhile, within the developing Protestant churches, rather than establishing a single authoritative text, a quest began. The purpose of moving to the Greek had been to return to the original, and so, gradually, the authoritative text moved from simply the best Greek manuscripts available, as compiled by Erasmus or Stephanus, to an attempt to establish ‘the original text’. Acknowledging that there had been changes, shifts, and transformations of the New Testament texts in various times and places, it is posited that it is the original text, as originally written by or under the authority of the apostles, which holds authority, and not any later additions or changes. The plethora of Bible translations that began to flourish in the 20th century in the United States evoked a similar response, with a certain segment of Protestantism privileging the King James Version, and through it the Greek texts on which it was based, over all others. One idea unites all of these views and movements, the idea that there is a real Bible to be found somewhere in the manuscript traditions of the scriptures in one language or another, and all other “Bibles” are to one degree or another false.

There are several problems with this approach to the Bible in general, and the New Testament in particular. For those who grant all authority to the ‘original text’, there is the great difficulty of even identifying what that means with reference to certain New Testament books. 2 Corinthians is a good example. St. Paul did not write his letters by hand. We know this because in the texts themselves, there are occasions when he does use his own hand, and he identifies the scribe who wrote the letters often. As was typical in the first century, St. Paul would dictate his letters to a scribe, who would write them, correcting and shaping grammar and the like. Then the letters would be read by St. Paul, who would perform additional editing. In the case of 2 Corinthians, it seems clear in the text that at least two of St. Paul’s letters to Corinth (he wrote at least four), have been joined together to form what we call 2 Corinthians. Further, around the year 100, St. Paul’s letters were collected together and circulated together as a collection from that point. All of the manuscripts we have of St. Paul’s letters come from these collections, either in codex or lectionary form. What, then, is the original text of 2 Corinthians? The words as they left St. Paul’s mouth originally? The words as they were first written on papyrus? The text after St. Paul had edited it? The original letters before they were combined? The first text of the combination? The text as it existed in the first collection? Further, none of these ‘original texts’ are texts which we actually possess, and so any proposed ‘original text’ is really the result of conjecture, and that hypothetical text is then called the ‘real’ text of Scripture, and all of the actual texts which we possess are therefore false texts.

For those who propose some later text or set of texts as being the ‘real’ text, there is a certain amount of the same difficulty, as all of these texts, whether the texts behind the King James Version, the Textus Receptus, or the Majority Text, are all compiled from multiple manuscripts. Meaning that these compiled texts were not found in anyone’s actual Greek Bible. Further, these texts are not the New Testament text as St. John Chrysostom preached it, or as St. John of Damascus studied it, or as St. Gregory Palamas would have recognized it. And this is the central, and most important point. All of these New Testament manuscripts are Orthodox Bibles. Whether it be Codex Sinaiticus being used from the 4th century at St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, lectionary texts from the Mar Saba Monastery in the 8th century, or 15th century Byzantine manuscripts, these are texts which were read, studied, and from which the truth of Jesus Christ was preached not just by Orthodox Christians, but by saints and fathers of the church. Our fathers in the faith took the scriptures as they received them in their worship tradition, including even in translation in other languages, as being the Scriptures. When the time came in 1904 for the Patriarchate of Constantinople to publish its first printed Greek New Testament, no effort was made to find an ‘original text’ or to establish the text of some particular era as authoritative. Rather, 250 of the lectionaries which were at that time being used in worship in actual churches in Greece were compiled to form the text.

The Holy Spirit was not only active in the ancient world to inspire the Biblical text as it was composed and brought together, but the Spirit has been active throughout the history of the church to preserve that text, and is behind the transformation of the text in various times and places. The Scriptures are themselves a tradition, really many branching streams of tradition in various places and languages, in which the Scriptures live. Rather than an exercise in archaeology or of submission to church teaching authority, every Christian receives the Scriptures within the community of the church, and receives them within a history of interpretation and application produced by the life of the Spirit within the church. The Scriptures for each person are the Scriptures which they have received in their own time and place and language. In our contemporary world, we have been blessed by God to have access to the wealth and vastness and richness of these traditions in their various eras and languages. Rather than this richness being a problem for us to solve by creating our own ‘real’ text, we have the opportunity to bring out of this treasury wisdom both new and old.

Another very insightful presentation Fr. Stephen. Thank you for producing and sharing these thoughts. I’m thinking that in the assimilation of the Christian writings into a single bound work, some prefer that the process remain blurred or hidden with no light shone thereon.