Now I say, that the heir, as long as he is a child, differeth nothing from a servant, though he be lord of all; but is under tutors and governors until the time appointed of the father. Even so we, when we were children, were in bondage under the elements of the world: But when the fullness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son, made of a woman, made under the law, To redeem them that were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons. (Galatians 4:1-5)

It was the Saviour Himself Who caused the star to announce His bodily birth, and it was fitting . . . that the King of creation on His coming forth should be visibly recognized by all the world. He was actually born in Judea, yet men from Persia came to worship Him. He it is Who won victory from His demon foes and trophies from the idolaters even before His bodily appearing . . . . The thing is happening before our very eyes, here in Egypt; and thereby another prophecy is fulfilled, for at no other time have the Egyptians ceased from their false worship save when the Lord of all, riding as on a cloud, came down here in the body and brought the error of idols to nothing and won over everybody to Himself and through Himself to the Father. He it is Who was crucified with the sun and moon as witnesses; and by His death salvation has come to all men, and all creation has been redeemed. (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation of the Word)

In order to effect this re-creation, however, He had first to do away with death and corruption. Therefore He assumed a human body, in order that in it death might once for all be destroyed, and that men might be renewed according to the Image. The Image of the Father only was sufficient for this need. Here is an illustration to prove it. (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation of the Word, 3.13)

History can go no further than the Incarnation. Indeed, it is from the Incarnation that history derives its very meaning.

The above two thoughts hold a double import, in that Christ is both the formal and final cause of the Cosmos and time.

First, we can think of history as the sweep of time, from the moment when God created the cosmos, that is, from when the entire ordered universe first sprang into existence by God’s Fiat to that moment when the final curtain falls on the world’s last night.

But second, we can also think of history in the sense of the meaning we impute to all that has happened — that is, what we think historians are doing when they do their work, making sense of the past. This hinges also on the Incarnation.

And the Church was rather quick to point this out, for some of her very first controversies–with the Docetists, the Marcionites, and the Gnostics–centered on the redeemability of time, place, and matter. In short, the Church was quick to defend the very real significance of history in our redemption.

In this regard, the Church stood athwart not just the heretics, but the whole world of Greek thought into which the Church had been born.

It’s not merely that we have divided history into BC and AD (or as the bien pensant like to say, CE and BCE, which are just words that still depend on the birth of Christ, all the while attempting to exclude our Lord– ah Shakespeare, a rose by any other name . . .), but it does build on the very insight that the great scholar the Venerable Bede wished to express: that Christ in His coming had reordered the world by His redemption of it, and that the books of the Old Testament, all of them inspired by the Spirit of Christ to testify about Christ and the Church, found their culmination and significance in Christ, when He inaugurated this new order. St. Bede had not created the calendar he used, but had adopted it (and it was already in use) from Dionysius Exiguus, but St. Bede did show how Christ revealed the Old Testament economy’s significance.

To St. Bede, what we find in the tabernacle of the Israelites, Solomon’s temple, and the renewed temple under Ezra and Nehemiah, were all precursors to the great and glorious Tabernacle and Temple who are Christ and His body the Church. He wrote separately on each of these, and they are well worth the read, showing how St. Bede employed allegory on historical texts, seeing each building’s fulfillment in Christ.

To St. Bede, what we find in the tabernacle of the Israelites, Solomon’s temple, and the renewed temple under Ezra and Nehemiah, were all precursors to the great and glorious Tabernacle and Temple who are Christ and His body the Church. He wrote separately on each of these, and they are well worth the read, showing how St. Bede employed allegory on historical texts, seeing each building’s fulfillment in Christ.

The history occurred not for its own sake only, since the full significance could not be found in the cloth and stone of these edifices — having been destroyed, they are of no lasting value — but in what they tell us of Christ. For St. Bede, the historical doesn’t vanish with the allegorical, but becomes its basis, for were the tabernacle immaterial, so too would be the Incarnation.

But more than this, to the Venerable Bede the solidity of the historical binds us to both the sanctity and the sin of our Old Testament fathers. After all, why should we fear a mythical wrath of God?

St. Bede is working off insights already given by others: Not so much the four-fold sense of Scripture, which he does embrace, but the centrality of the Incarnation as the basis of his hermeneutics. Christ came in the very midst of history, into a world especially prepared by the providence of God (a note repeatedly played since the fourth century, extending from Eusebius and St. Athanasius, at least, onward), and those who took up this thought did so in direct opposition to the thought of Greeks in its various guises.

For Greek thought, stemming from Plato, this visible, sensible world is an insubstantial world, a world of chaos and change (in this regard, Plato assumed Heraclitus’ physics as a precursor to his doctrine of the forms), but which constantly resolved itself into the patterns being pressed upon it by the real and substantial world, that is the world of the immaterial, intelligible, and substantial forms. Thus, history, made to conform to the ideas or forms, was cyclical, and all events just repeated themselves in an unending march.

This circular nature to reality is reflected in the intelligible organ for Plato, the mind, as all thinking ultimately was circular, thought proceeding from the intelligibles and resolving itself in them. This is why human heads were spherical, he conjectured, and the heads of brutes were elongated.

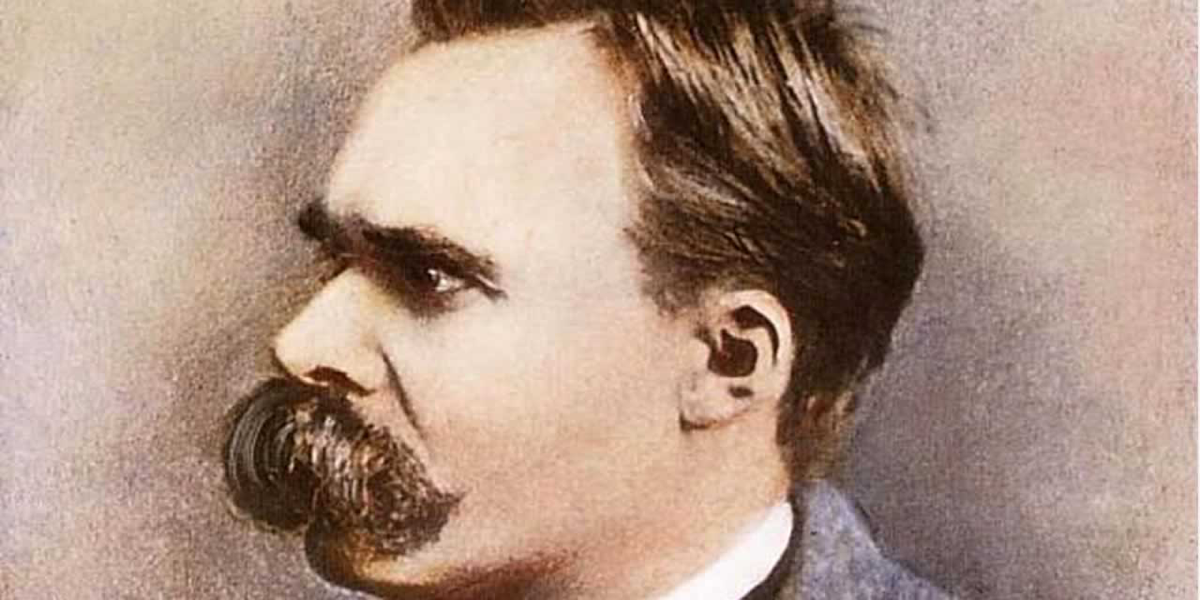

History was static. No instance of time was significant, for it would just happen again. It is not without irony that this was the view of history of the father (or one of them) of the twentieth century, Friedrich Nietzsche, whose doctrine of the eternal recurrence meant that nothing done had any real importance. He dreamed of himself as the prophet of the Übermensch (the one who would break the cycle), but of course could never quite bring a resolution as to how the Übermensch would appear.

History was static. No instance of time was significant, for it would just happen again. It is not without irony that this was the view of history of the father (or one of them) of the twentieth century, Friedrich Nietzsche, whose doctrine of the eternal recurrence meant that nothing done had any real importance. He dreamed of himself as the prophet of the Übermensch (the one who would break the cycle), but of course could never quite bring a resolution as to how the Übermensch would appear.

We see the early Church’s stance against this clearly in St. Athanasius, who, as demonstrated by the quotes above, from a text written when he was but in his early twenties (that is, at about the same time Eusebius was writing), saw that the Incarnation had altered history from a march toward decadence and the void into one that is now moving all things, humans and the rest of the created order alike, toward the source of their existence, their telos if you would, into the kingdom of the Incarnate Christ. This kingdom has broken into history and is toppling the idols of the pagans that had sought to supplant the knowledge of the true God (cf. the quote above).

This same note is sounded in Eusebius of Caesarea both in his Ecclesiastical History and his Encomium of Constantine, where the course of history had been driven by divine Providence to bring us Christ at just the right time, and Christ’s kingdom had now conquered the greatest kingdom of the world, Rome.

Eusebius could speak out of both sides of his mouth (he was a courtier as well as a bishop), for in his Demonstratio evangelica and his Praeparatio evangelica, he could speak of the excellence of Christ as the fulfillment of the expectations of the pagans as well, and that Old Testament religion, though belonging to the Christians, was but a stop-gap from the pure religion that existed before the fall. But ultimately, even in his less robust moments, Eusebius still holds forth Christ and his life as the pinnacle of history.

It should not be thought that the early Church spoke with one voice against the Greeks, as there were real dissenters, and perhaps none more so than Origen. Origen was so weak on the significance of the created order that the famed patrologist J. N. D. Kelly wondered whether Origen was the left wing of the Church or the right wing of the Gnostics.

It should not be thought that the early Church spoke with one voice against the Greeks, as there were real dissenters, and perhaps none more so than Origen. Origen was so weak on the significance of the created order that the famed patrologist J. N. D. Kelly wondered whether Origen was the left wing of the Church or the right wing of the Gnostics.

Origen in his De principiis 1.2 lays out that the spiritual order existed in a state of perfection, co-eternal with the preexisting Word, and that its fall is the ruin that Christ came to restore. Thus, the Kingdom of Heaven is just a restoration of prehistory, and not at all a fulfillment and completion of creation. Indeed, there is nothing new in history, and to quote Jean Daniélou: “It would have been better if nothing happened at all, and everything had remained in its primordial stability” (The Lord of History).

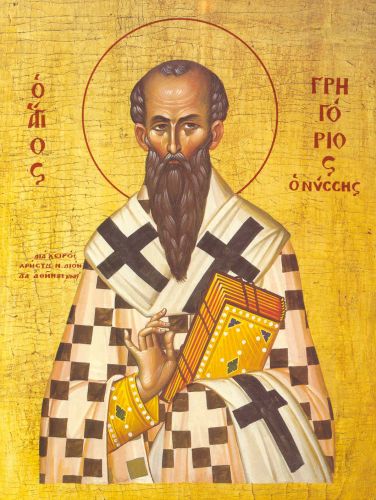

But Origen found himself answered, from both east and west, even by those who owed him intellectual debts (and make no mistake, the Church does owe a debt, but certainly not fealty, to Origen), and in particular St. Augustine and St. Gregory of Nyssa.

The second is all the more important, since so many glom St. Gregory onto Origen, it would seem, hoping to rehabilitate the latter. But Origen seems to have no notion that those things that have a beginning can also have no ending–thus, Origen’s notion of the preexistence of the soul.

But for St. Gregory, however we view his take on the apokatastasis (which seems to come to a rough handling in his Address on Religious Instruction), in his sermons on the Song of Songs, which reads very much like a patristic epistemology, he speaks about history as proceeding “from beginnings to beginnings, by successive beginnings that have no end.” (Large sections of Daniélou’s translation can be found in the SVS book, From Glory to Glory.) One can find this thought about the eternality of the created throughout St. Augustine’s The City of God as well.

And thus the whole of history has descended to us even now by means of the ever-presence of the Incarnation. It is in the Incarnation that our own lives have meaning, that the acts we perform on behalf of God, the love we have for spouse, children, friends, and perhaps most of all, our enemies, shall not prove to be some ephemeral acts, but substantial realities that are part of the life of each Christian in Christ, and thus of eternal significance.

And these acts of virtue are our part as well in the triumph of Christ over the powers of this world, part of our trampling Satan under our feet. Christ’s Incarnation was a crushing of Satan, His ministry through his Apostles brought about the casting of Satan “like lightning” out of heaven. We join with St. Michael and all the angels in this battle.

But beyond this binding of Satan, we are also in our redemption redeeming all of the cosmos with Christ, bringing the order of the world not back to its original order in the garden, but into the garden now fully cultivated. We already realize the crushing of death and corruption, begun in Christ, who by his death destroyed the death we had by dint of our mortality. Further, we now have obtained through Christ, the Christ with Whom we are vested by our baptism, a communication of His immortal life by His giving Himself to us in the Eucharist.

For St. Gregory of Nyssa, our composite nature, by which we dwell both in the created and uncreated realms, needs the historical, the sensible, and not just the intelligible (though it needs this too) for its salvation:

Owing to man’s twofold nature, composed as it is of soul and body, those who come to salvation must be united with the Author of their life by means of both. In consequence, the soul, which has union with him by faith, derives the means of salvation by faith. For being united with life implies having a share in it. But it is in a different way that the body comes into intimate union with its Savior. Those who have been tricked into taking poison offset its harmful effect by another drug. The remedy, moreover, just like the poison, has to enter through the whole body. Similarly, having tasted the poison that dissolved our nature, we were necessarily in need of something to reunite it. Such a remedy had to enter into us, so that it might, by its counteraction, undo the harm the body had already encountered from the poison. And what is this remedy? Nothing else than the body which proved itself superior to death and became the source of our life. For, as the apostle observes, a little yeast makes a whole lump of dough like itself. In the same way, when the body that God made immortal enters ours, it entirely transforms it into itself. When a poison is combined with something wholesome, the whole admixture is rendered as useless as the poison. Conversely, the immortal body, by entering the one who receives it, transforms his entire being into its own nature. (St. Gregory of Nyssa, Address on Religious Instruction 37)

The Eucharist is both our participation in the life of the world to come and our participation in the pinnacle of history, that moment in the fullness of time which gives life to all, both our fathers and mothers in the old economy, from Adam to John the Baptist, and to us now, “God having provided some better thing for us, that they without us should not be made perfect” (Heb. 11:40).

The Gnostic fantasy of seeing history as a mistake, the physical world as an aberration in need of obliteration, has returned in our day with a fury. How could we not expect this, when once modern thought had said we are no more than our bodies (a lie the mind can  hardly bear to contemplate)?

hardly bear to contemplate)?

The pessimism that this brings leads us right back to the basic Gnostic assumption that something is wrong with creation, wrong with time, wrong with history. Modern literature from Voltaire to Camus is fraught with the absurdity and irrationality of a world bereft of a transcendence that has also broken into history. Consequently, rejecting this, but instead of turning to the Faith, people no longer believe that they are their bodies, and this present physical world masks a reality that transcends the historical and the creaturely.

This stands in stark contrast to a view of reality centered on Christ as both Creator and Redeemer. For the Christian, the union of our nature with Christ in His one Person, even that deified human nature that we receive in the Eucharist, unites us at this present moment with that pinnacle of history which is the Incarnation, and by it we are tied to our fathers and mothers of the old covenant.

There we have found the goal of history, and what flows from that informs all our actions in history. In this regard, without the Incarnation we become ahistorical entities, striving after unhistorical utopian visions rooted in an anthropology that disdains the historical, chasing ever after a perfection divorced from the reality of a world limited by the order of God, a world in rebellion to God, seeking a justice divorced from Christ.

Dr. Jenkins

I found this to be a very interesting article. I have known for a little bit of time that the Holy Creator is not subject to “time or space” as we humans are. People who believe that He is should probably be asked these two questions. Is the Author of the latest New York Times best seller subject to page number thirty five? How can the book restrict the authors ability to do anything? It was not the book who made the author was it? The same is true of time and space it is controlled by God.

This brings me to my next point. I have an allergy to vine berries. Grapes are vine berries and as we all know Wine is a grape product. (Many Protestant churches use grape juice instead of wine) My allergic reaction is a three day migraine, a bloody nose and a sore throat. However, as of late I have noticed that if “The Host” has been properly consecrated, I have no ill effects from partaking in the Eucharist and it doesn’t matter if its wine of grape juice.

Now just to test to see if my body had changed from being allergic I had a thimbles worth of grape juice two weeks ago. The result of which ….

Yep!! I’m still allergic to vine berries and very allergic to grapes as it turns out. So I have no doubt that something is definitely changed during the consecration and the prayers both before during and after Holy Communion.

Let the secular world explain that if they can!

Thank you for this! I have read it several times, each time understanding a little more.

“How could we not expect this, when once modern thought had said we are no more than our bodies (a lie the mind can hardly bear to contemplate)?” I remember as a teen when I first realized I would eventually die.. Trying to think about my non-existence, convinced I was nothing more than organic material — was terrifying. Thanks to God, this darkness was later removed in Christ!