I do not know how aware most folks are of what books shape their basic imaginations—the formation that to a large part determines what brings them delight, what strikes them as worth attention, what gives them a vocabulary for the world. For me, there are really two sources that give me that shape—the Bible and the fiction works of J. R. R. Tolkien. This post is about the latter.

Today would have been his 122nd birthday, so I’m thinking about him especially today. Now, I know that he has been so much talked about that I am sure I cannot say anything original about him, but I did want to mention how what he wrote has shaped me, at least in some points, and perhaps that might be of interest to a few readers.

It’s not so much that I see hobbits and dragons everywhere, mind you (though it is arguable whether there are still dragons about). I think most of what I’ve unconsciously absorbed from Tolkien is his use of language. I don’t use Commonwealth English spellings, to be sure, but I still have an inner feeling, for instance, that the plural of dwarf should be dwarves and not dwarfs (a usage that put Tolkien at odds with his contemporaries and countrymen). (He also insisted on elven over elfin.) And I will also admit to indulgence in archaisms, as well, not because I think they make the user sound smart or artful, but just because my inner sensibility is that this is just how language ought to sound at its best.

But there are other things, too. I recall when I was a teenager and then in my twenties, that a young lady who seemed most attractive to me was best described for me as an elven-maid. No doubt some of my belles didn’t quite get the level of compliment I was paying them, that I was comparing them to the race that was highest, most beautiful, most noble and immortal. Mind you, men have been calling women that kind of thing since at least Petrarch, but for me, there is something specifically elven about that business. And though my wife would probably find it silly, there is certainly something for me that is elvish about her, though there is also quite a lot that is hobbitish about her, too. She is a civilizing person in the sense peculiar to both those races.

I really don’t remember the first time I read The Hobbit, though I think I was quite young. My family owned a large illustrated edition put out at some point in the ’80s (long ago fallen to pieces), as I recall, using pictures from the Rankin-Bass cartoon that I still love. (To this day, when I read Tolkien’s Middle-earth books out loud, the voice I do for my kids for Gandalf is not Ian McKellan but rather John Huston.)

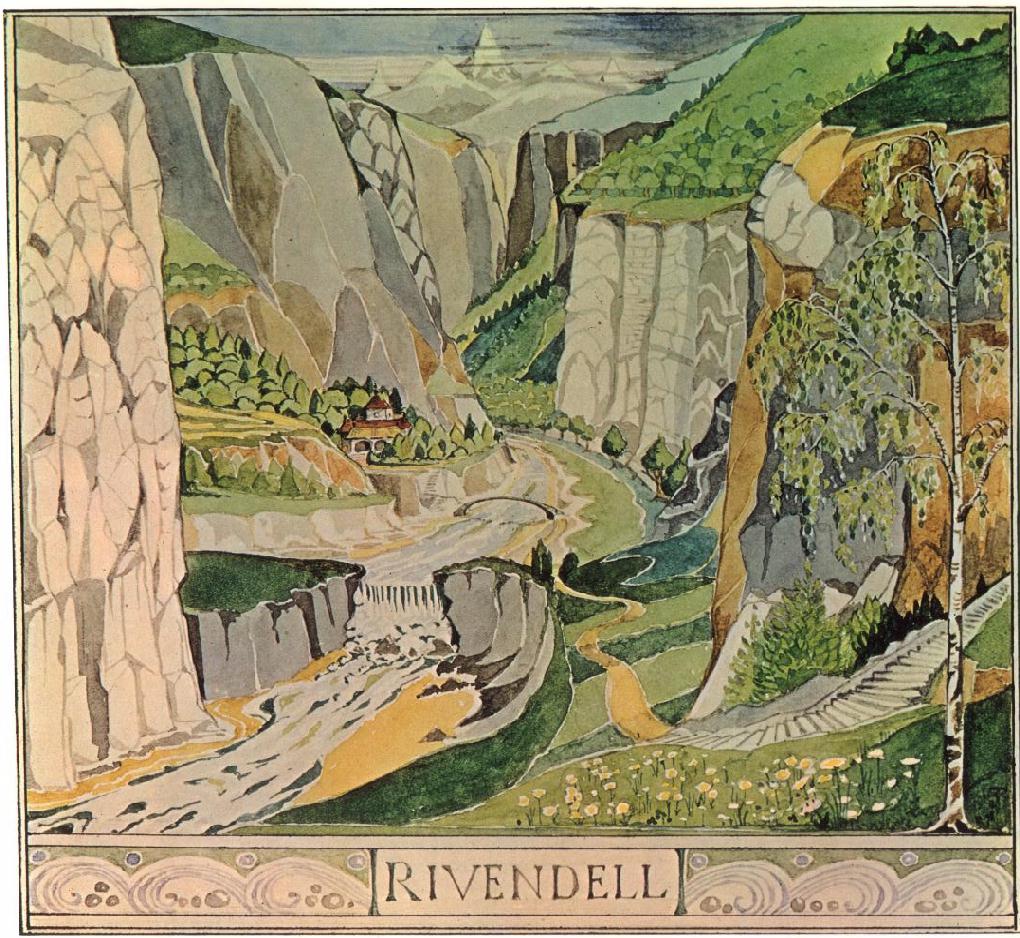

My dad had old paperback editions of The Hobbit and the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings from the ’60s that were yellowing and adorned with Tolkien’s own illustrations on the covers. I received them all at some point. They are too brittle to be read, but they still have a pride of place on my highest shelf, next to several “reading” copies of the same books, and a couple large “heirloom” copies in slip covers.

I don’t think I finally read The Lord of the Rings until I was in high school, and I’m not really sure why. Certainly The Hobbit had always delighted me. But perhaps my imagination was not quite ready for the degree of complexity that the latter book has in comparison with the former, shorter volume. In any event, I came away from my first readings of the three-volume book with a sense that Middle-earth was a place I very much wanted to go and even to live.

And what I received most from those books at that time was something that has long stayed with me—a sense of longing for what has been lost. Loss is a major theme especially in the larger story, and it’s touched on particularly by Aragorn and the Elves, who all remember much that has been lost and mourn it.

It may well be that this sense of desiring what is ancient and powerful had a strong influence on my first encounter with Orthodox Christianity in my early twenties. Here was contact with what was not only older than my world, but very much better. Yet unlike in Tolkien’s world, what has been lost for the Orthodox Christian can actually be recovered and restored, yet it can only be recovered to the degree that we internally realize we have lost it—not “Holy Russia” or “the glories of Byzantium,” but rather the loss of innocence and purity in the human soul. Some writers have called this aspect of Orthodox spirituality “nostalgia for Paradise.”

This thing more than any other from Tolkien is what shapes my imagination and informs much of my thinking and even feeling—a kind of melancholy of remembrance. But unlike Renaissance melancholy with its dark obsessions (which very much interested me in my undergraduate days), it is a remembrance that brings beauty into the present.

And for that, I will always be grateful. And I will also teach it to my children, mainly just by reading to them.

Thank you for your reflections.

I first read Lord of the Rings early in high school, then read it twice more before graduation. Greatly affected my thinking and the way I began to look at the world around me. Didn’t read The Hobbit until the summer before my senior year. Appreciated it for the back-story–especially Tom Bombadil ;o)

What does stir the soul to grieve and then long for the paradise lost? I’m not at all sure but suspect the Holy Spirit. And God has not left us without other of our own kind, humans uniquely gifted like Tolkien to help us along the road to a restored beauty. Thank you Father for your work and labors before us.

Father Bless,

This was a timely post, I first read “The Fellowship of the Ring” at twelve and it has made a profound influence on my life, it was a good counter point to my other secular reading and is at times a positive influence, and at times I despair in my writing ability knowing that I can never accomplish what Tolkien did, yet it is his standard that I measure myself against and if I only get it a tenth as good as he did, I will be doing absolutely great. I knew there was something about ya when I first met you that I could not put a finger on, now I know that you also do not put Tolkien in the meanevilnasty category that some Christians (Heterodox and Orthodox alike) do, and are willing to bring him along on your walk with Jesus. Thanks for sharing and have a blessed new year.

I tried to watch the Rankin-Bass cartoon some time ago and couldn’t. I love the animation but the songs were so so bad even my nostalgia could not keep me listening! I do love Tolkien’s writing though; very beautiful.

I wish my parents had had “The Hobbit” for me to read as a child. I know it would have been much the same sort of touchstone for me—though the Rankin/Bass “Hobbit” was certainly a big deal for me back then. Despite it’s flaws, it’s far better than the new, shiny, made-up version.

I do know which books formed me, though, because I can still feel them pulling on my brain as an adult: “The Secret Garden” most especially, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, this one little book of Greek myths that I read about a hundred times, and “The Chronicles of Narnia.”

I really enjoyed this post. I did not discover the brilliance of Tolkien until I was an adult. And, I don’t think it’s by chance that it coincided with my discovery of the ancient faith. I can relate to your thought very much here:

“it may well be that this sense of desiring what is ancient and powerful had a strong influence on my first encounter with Orthodox Christianity in my early twenties. Here was contact with what was not only older than my world, but very much better.”

And I have often said similar about the Bible and Tolkien bearing the most influence on my spiritual life. For the shaping of my religious thought, Tolkien had the largest impact on my understanding of symbols and all the complexities that entails. His writings of loyalty, sacrifice and love are dear to my heart in LOTR– and after reading the Silmarillion, I became captivated by the beauty and insight he gives to the question of origins … of a supreme being and his creations.. and the nature of evil. Truly fascinating; his writings are to my eyes what Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky are to my ears. The creative gift that goes straight to the heart and soul.

An excellent summary of Tolkien’s relevance to Orthodoxy, Father.

For Tolkien, Lord of the Rings was “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work” replete with Catholic themes, including the nature of creation, sin, and evil as well as redemption and justice. So it isn’t surprising that you would sense that, and that it would lead you to a deeper realization of heavenly realities.

Of course, Tolkien in a letter to a friend said that the chief character in LOTR was God 🙂

So much yes! I know that’s probably not grammatically correct, but you articulated so well how I have felt and still feel to this day. “nostalgia for Paradise”, “a kind of melancholy of remembrance”. These two things have been a part of me ever since I can remember. One of my favorite quotes by C.S. Lewis is, “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” I suppose that’s why I have always possessed a love for the old ways and old things. I realize now that I was always meant to become Orthodox. One of the best decisions I have ever made. Glory to God!