I feel that as long as the Shire lies behind, safe and comfortable, I shall find wandering more bearable: I shall know that somewhere there is a firm foothold, even if my feet cannot stand there again. —Frodo Baggins

I happened upon this quotation again yesterday evening, while I was reading my daughter The Lord of the Rings. It seems a dauntingly long tome to read to a five-year-old, but of course we have years, if need be. She’s also already listened to the whole of The Hobbit and liked what she heard and wanted to hear more about hobbits. So of course I could not resist. Naturally she will not remember everything or understand all the details this time around, but that doesn’t particularly matter. So it goes with all of the good tales for any of us, including, I think, the Book itself.

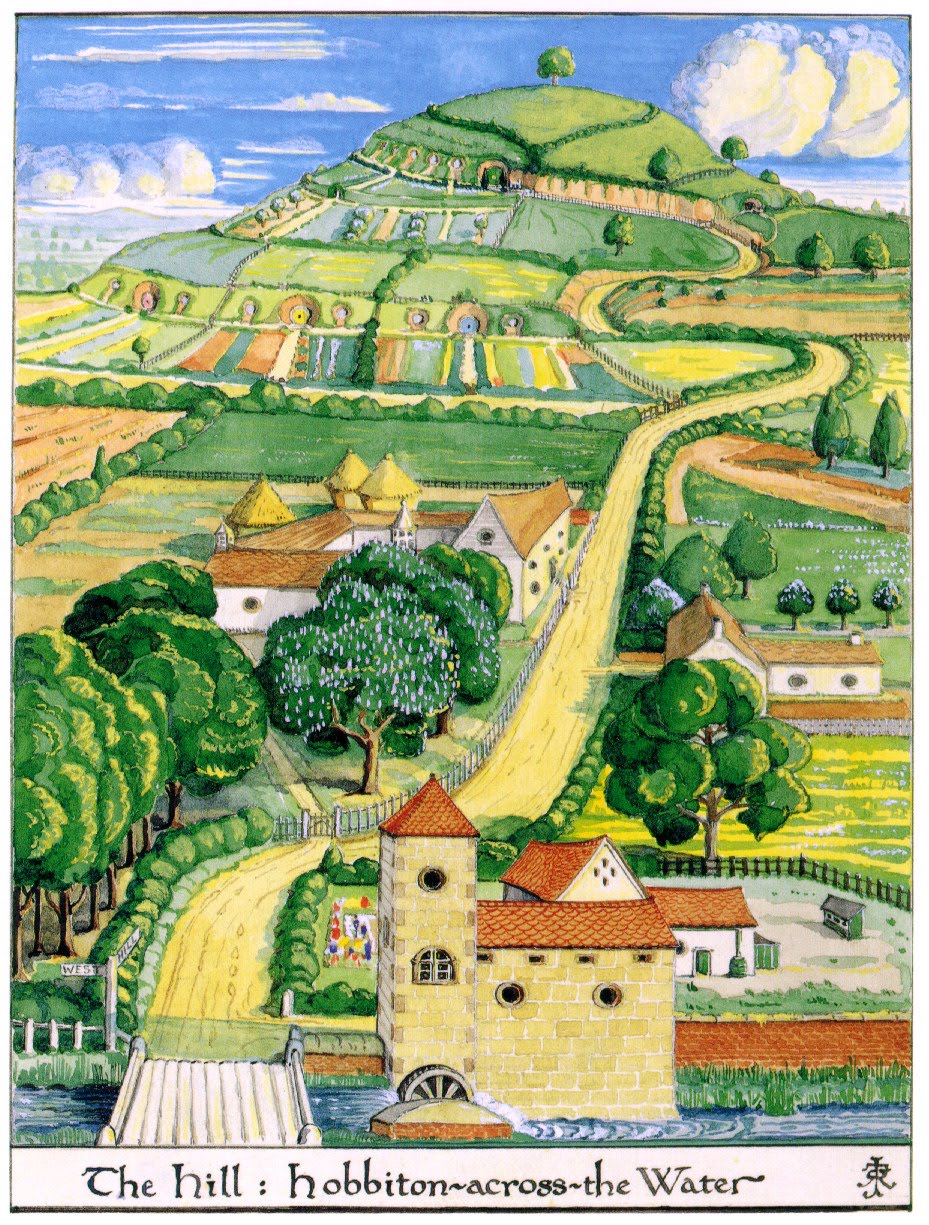

As someone who is in some sense homeless (though not houseless), having lived now in twenty-two separate dwellings across fifteen towns, six states and one unincorporated territory, these words from Frodo in anticipation of his great Quest always make me a bit sad. Much of Tolkien’s work is about a sense of loss, of remembering things that never will return, and when Frodo speaks these words to Gandalf, he has no idea yet how much he will lose, that he will indeed lose the Shire for himself, even while he saves it for others.

The sadness that I feel is not quite Frodo’s sadness, though, because there is no geographic place that I have left behind and can return to or at least hope for while I am in my wanderings. And while I do intend to spend the rest of my days here in Emmaus, I think that it is too late for me to have a home. Though I am not old, I am too old for that. I’ve done it backwards from Frodo—I have tried to find a home after my wandering rather than embarked upon my wandering from a home already found and already loved.

My point here is not really about me, though. My life is what God has permitted it to be, even if I’ve muddled it up here and there, and I am grateful for what I have received. No, the point is about that “firm foothold” that Frodo mentions. For him, it is the Shire, and he carries memories of the Shire throughout the Quest to destroy evil. I do not have a Shire of my own, not in the sense that there is some specific place I can place my mind’s feet to gain that firm foothold.

But even though some of us are homeless in this life, I think that we nonetheless have the possibility for such a firm foothold, for a memory of beauty and homeliness (to use homely in its British sense, roughly homey in American English, though not so rustic). I hope I can say this without sounding like a romantic, but for me that firm foothold has become the worship of the Church, most especially in its Byzantine iteration, with which I was first imprinted in Orthodoxy. It is not quite the same as having a home in the earthier sense—a sense I encourage all to develop as best they can, even in such a homeless state as I find myself—but there is certainly a firm foothold to be had there, a power and glory and sense of belonging that can be carried along in any place of wandering, any struggle, any peril, as we pursue our own great Quest.

There are many instances throughout the history of the Church in which the saints, those people who were most infused with God’s presence here on earth, did something peculiar as they faced imprisonment, torture and even death—they sang hymns. I cannot help but think that their experiences in worshiping the one True God in His Body the Church became for them the firm foothold that made their wandering bearable. And when faced with the gravest of circumstances, they called to mind that power and energy, and they brought it forth again in an act of anamnesis (a term usually referred to the invocational memory that brings Christ’s passion and death into the here and now as the Eucharist). While Frodo could only engage in mneia (recall), we Christians have the possibility for anamnesis, bringing the Savior Whose salvation we remember into the very present by means of collective invocational memory.

As we do that, the orcs and Uruk-hai and evil wizards and the Ringwraiths and even the Enemy himself can be borne rightly, with patience and even with love and with joy. And in so doing, like Frodo, we can also destroy evil and loosen its hold on our hearts.

Father, bless!

That is, almost exactly, what I feel in Orthodoxy and why I never left once I visited. Thank you for your wonderful words.

That resonates for me, too… I actually lived my whole young life in the same area (albeit in several houses/apartments) but when I think of home my heart goes to All Saints.

We are, after all, sojourners in this strange land, aren’t we?

My first thought on reading this post was: Keep reading! We read LOTR to our son when he was five, and he is now (at 33) an avid reader and accomplished author. Don’t let anyone tell you that Tolkien is “inappropriate” for a young child.

And my second thought was of Him Who said, “The Son of Man hath not where to lay His head.” You’re in good company, Father.

I love it when Orthodox , Anglicans and Lutherans reference Tolkien (and even Lewis, but mostly Tolkien).

Your post “A FIRM FOOTHOLD” struck a chord with me as well. I have no home to return to as the one place that I call home no longer exists. The city still exists of course but not as I remember it. The first 6 years of my life from birth until we moved was imprinted as ‘my home’. It remained fairly unchanged until I graduated high school and moved even further away. Four years later when I returned for a visit, it was unrecognizable. Virtually everything that once made it home was gone or changed so radically that I have never been able to return.

Professor Tolkien was a unique Roman Catholic writer in that he wrote to the mind and the heart of people. His Catholicism formed and informed him in a way that speaks to all traditional Christians and even others.

For those interested in learning more, Father Andrew Phillips on his website ‘ORTHODOX ENGLAND’ has archived an essay, “Orthodoxy in the Shire” – A Tribute to J R R Tolkien

by Eadmund Dunstall.

Also, traditional Catholic Joseph Pearce has 2 books on Tolkien, Tolkien: Man and Myth and also Tolkien: A Celebration. Collected Writings on a Literary Legacy. He also has a 1 hour DVD from EWTN “TOLKIEN’S LORD OF THE RINGS:CATHOLIC WORLDVIEW” and

from Catholic Courses “THE HIDDEN MEANING OF THE LORD OF THE RINGS” The Theological Vision in Tolkien’s Fiction. This is available in DVD, CD, and audio and video downloads and it is excellent.

I may not be able to go home again or have Frodo’s Firm Foothold but I still carry it in my heart.

Thanks again Father for this.

Amin! I am currently reading LOTR to my son. It is because of those spiritual parallels that my husband and I have such an appreciation for these stories. Thank you!

Wonderful. I am reminded of r.a. lafferty’s story “Land of the Great Horses” in which he writes of the Romany people’s lost (and regained) home in a sciencefictional way. In his afterword he notes “We are all Romanies, as in the parable here, and we have a built-in homing to and remembrance of a woollier and more excellent place, a reality that masquerades as a mirage. Whether the more excellent place is here or heretofore or hereafter, I don’t know, or whether it will be our immediate world when it is sufficiently animated; but there is an intuition about it which sometimes passes through the whole community. There is, or ought to be, these shimmering heights; and they belong to us.”

That is the essence of true home. Lafferty was, like Tolkien, a devout RC who went to daily mass.

and of course your post made me think of, from Tolkien himself:

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

I too, have been homeless all my life, and in much the samw way as Father Andrew; but for me, it is not a memory of the Shire that gives me strentgh. It is Numenor; and that is a loss and a tragedy beyond the breaking of the world. Like Faramir when he lifted a toast in silence to the setting sun, I remember Constaniople, and the years 1204 and 1453 bring a bitter memory. But the healing that comes with the Holy Euchrist softens that bitterness; only a gentle saddness remains. And a hope, for a future beyond the Circles of the World.

Well, that’s an interesting thought, but it strikes me as not really the same thing. Frodo’s Shire was a place he actually knew and loved, and while Faramir of course had never been to Numenor, he belonged to its royalty and tradition in a way that none of us now alive really can connect with Constantinople except perhaps only with a kind of romantic sentimentality. In any event, I daresay Faramir is far more driven by love for Gondor than for Numenor.

In any event, my point here is not really to be propelled along by what is lost, and none of Tolkien’s heroes really are, either, though they feel their losses keenly. Rather, they are motivated and inspired by what they seek to save, by their love for what they truly know and experience.

Father you are just getting started. I have read aloud to my son The Hobbit, The Once and Future King, AND the Brithers Karamazov. (Among others.) We did, however, listen to CDs for TLotR!!

Tried posting Wed. night but lost power just before finishing & could recover!

But thinking more, I believe we see Classic literature picking up this theme we see in holy scripture – man longing for his ‘place & home’. Abraham sought for a city and land whose maker is God. And we learn that Canaan is a mere shadow or foretaste of that heavenly city — the whole new heaven and new earth, groaning for redemption – our inheritance richly to enjoy. It is most interesting that we instinctively connect this above to our communion and community together at the Eucharist – another real shadow and sweet foretaste of that theosis we yearn and long for in soul and body, with the communion of Saint together, in union with Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This also not only hints again at the poverty of individualism, but all notions of a disembodied non-material eschaton?

could “not” recover. I should also have included the Agrarian writings of men like the southern Fugatives poets, Richard Weaver, then Wendell Berry along with European Distributists. Aussie Gefforey Lilburn has an excellent book, _A Sense of Place: A Theology of the Land_ but does not connect the longing for community & true communion to the Eucharist, Theosis or the Eschaton.

This post reminds me of Alexander Kalomiros’ book, “Nostalgia for Paradise,” which I picked up at my parish booktable. In the introductory chapter, he writes:

“The Christian life is a nostalgia for Paradise, a deep knowledge that we are foreign travelers in a passing and vain world, far from our true Fatherland. The saints dwelt in Paradise even in this life. When we read their writings, we feel as if they are taking us by the hand and leading us to a fragrant garden of beauty, of tranquility, of eternal life. This is how nostalgia for Paradise is born in us.

“Nostalgia is a great force. It contains something of sorrow, something of love, and something of joy. The Fathers make us nostalgic for God. Anyone who is nostalgic for God labors to return to Him. This is the labor of Christians. They stand before the angel’s flaming sword and, weeping like infants whose milk has been taken from them, they wait for the angel to step aside. Exiled from two paradises, the paradise of men and the Paradise of God, they are strangers and sojourners, transients in this world.”

Ever since I have been a Christian, I have had the sense that no place here on earth is truly my home. I’ve no doubt that this sense is connected to losing both my parents and two of my brothers within four short years and by the age of 21. A wandering pilgrim, in the world but not of it, is how I regard myself. But should not all Christians regard themselves as pilgrims looking forward to their eternal home – the Celestial City of which John Bunyan wrote?

Hebrews speaks of those saints who have gone on before “of whom the world was not worthy.” A deep longing penetrated the depths of their souls – a longing for a place where all would be made right, a place where they would gaze upon their Saviour. Such hope propels Christians in the midst of suffering to look beyond this life and know that their redemption is nigh.