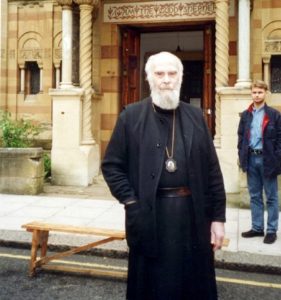

Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of Sourozh is one of my favorite modern writers because, even though I have not really even begun to read all of his that is available in English, whenever I read something by him, I immediately feel a sense of hope in Jesus Christ. His transparency and peace are immediately accessible in all his writing. And since there is still so much more for me to discover from him, there is also a little revelation every time I read something new. (And there is a growing archive of his works online which makes that more possible.)

I had the blessing of meeting him briefly in 2001 when I visited his cathedral in London. I was brought to a room adjoining the altar area, and he came out to meet me—probably because I had it in my mind that, because I was a tonsured reader, I ought to wear a cassock whenever I went to church (I later learned that that is not really appropriate for the minor clergy in the tradition I serve in). However presumptuous I was, it afforded me to meet this man.

When I saw him, my immediate first thought was Here is a man who loves me. It was not the sense of seeing someone I knew and loved myself, but rather a sense of being loved by someone who had no reason to love me. But there it was. We spoke briefly.

I have ever since remained convinced of his genuine sanctity. And I have also kept a photograph of him on my desk, recommended his work (especially Beginning to Pray), and prayed for the resting of his soul (though I do have some doubts that he needs my prayers).

So as I was doing some work today for a class we’re about to finish up here in Emmaus, I ran across the following passage from the introductory essay in Meditations on a Theme:

When we think of spiritual discipline we usually think in terms of rules of life, rules of thinking and meditation, rules of prayers, which are aimed at drilling us into what we imagine to be the pattern of a real Christian life. But when we observe people who submit themselves to that kind of strict discipline, and when we ourselves attempt this, we usually see that the results are far less than we would expect. And this generally comes from the fact that we take the means for the end, that we concentrate so much on the means that we never achieve the end at all, or that we achieve them to so small a degree that it was not worth putting in all that effort to achieve so little. This results, I believe, from not understanding what spiritual discipline is and what it is aimed at.

We must remember that discipline is not the same thing as drill. Discipline is a word connected with the word ‘disciple’. Discipline is the condition of the disciple, the situation of the disciple with regard both to his master and to what he is learning. And if we try to understand what discipleship means when it is put into action, when it results in discipline, we may easily find the following things. First of all, discipleship means a sincere desire to learn and a determination to learn at all cost. I know that the words ‘at all cost’ may mean a great deal more for one person than for another. It depends on the zeal and the conviction or the longing we have for the learning. Yet it is always ‘at all cost’ for this particular person. A sincere desire to learn is not so often to be discovered in our hearts. Quite often we wish to learn up to a point, provided the effort will not be too great, provided we have guarantees that the final result will be worth the effort. We do not launch into this learning wholeheartedly enough and this is why so often we do not achieve what we could achieve. So the first condition if we wish to become disciples fruitfully and learn a discipline which will give results, is integrity of purpose. This is not easily acquired.

We must also be ready to pay the cost of discipleship. There is always a cost to discipleship because, from start to finish, it means a gradual overcoming of all that is self in order to grow into communion with that which is greater than self and which will ultimately displace self, conquer the ground and become the totality of life. And there is always a moment in the experience of discipleship when fear comes upon the disciple, for he sees at a certain moment that death is looming, the death that his self must face. Later on it will no longer be death, it will be a life greater than his own, but every disciple will have to die first before he comes back to life. This requires determination, courage, faith.

This being said, discipleship begins with silence and listening. When we listen to someone we think we are silent because we do not speak; but our minds continue to work, our emotions react, our will responds for or against what we hear, we may even go further than this, with thoughts and feelings buzzing in our heads which are quite unrelated to what is being said. This is not silence as it is implied in discipleship. The real silence towards which we must aim as a starting point, is a complete repose of mind and heart and will, the complete silence of all there is in us, including our body, so that we may be completely aware of the word we are receiving, completely alert and yet in complete repose. The silence I am speaking of is the silence of the sentry on duty at a critical moment; alert, immobile, poised and yet alive to every sound, every movement. This living silence is what discipleship requires first of all, and this is not achieved without effort. It requires from us a training of our attention, a training of our body, a training of our mind and our emotions so that they are kept in check, completely and perfectly.

There is so much to quote from that essay, but this piece of it especially shone out for me in relief today. I am reminded that so many of us who are trying to be serious Christians, whether raised as Orthodox Christians or having embraced the faith later in life, quite often “take the means for the end.” I am guilty of this myself, many times over.

There is so much to quote from that essay, but this piece of it especially shone out for me in relief today. I am reminded that so many of us who are trying to be serious Christians, whether raised as Orthodox Christians or having embraced the faith later in life, quite often “take the means for the end.” I am guilty of this myself, many times over.

We should be wary of this when speaking about the Christian faith, especially when speaking of the shortcomings of others. In these moments, our admonitions to others to agree with us are often almost wholly focusing on what is hard, as though the hardness of it is what makes it true, as though we can through our words drill into someone “what we imagine to be the pattern of a real Christian life.”

If someone reacts against this hardness, I may say that I am “speaking the truth in love,” but I have found that anyone who says this about himself probably is not. You don’t have to tell someone you love him. It should be apparent to him. And the One Who is Truth Himself always speaks in love and doesn’t have to convince anyone of His love.

Maximos the Confessor once wrote that “virtue exists for the sake of truth but truth does not exist for the sake of virtue.” Virtue is a means to truth, not the end. We cannot mistake virtue for truth. It may be virtuous to be correct about everything, but if our correctness is not for the sake of truly knowing Him Who is Truth and Love, then we are in fact incorrect. If someone has to wonder whether I really love Jesus, then I have failed to speak the truth in love.

And thus the identifying characteristic in this mistake is that there is not any love detectable in my words.

It is true that some people reacted very badly to the love even of Jesus, but when someone is reacting very badly to me, I should check very carefully whether it is because I am embodying Christ’s love or something else. (Usually, it’s something else.)

I love here, however, Metropolitan Anthony’s description of what it means to be a disciple, especially what it means to be a listener. This goes well beyond the “good listener” trope we often encounter in our culture. It is something rather more potent. And it requires truly dying to self. And it also requires the kind of love that hangs on the words of the beloved.

Am I that kind of listening disciple, the kind who loves?

If I am, then all the discipline makes sense and will draw others to Jesus Christ. But if I’m not, then the discipline becomes a kind of anti-evangelism, and it will be small comfort as I look at the world who rejects the “Jesus” I offer and therefore imagine myself to be better.

One of the themes of “Everyday Saints” is that there are no coincidences. Just this morning (a travel day; lots of airport time) I finished an interesting book — learned of it from one of Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon’s podcasts — called, “The Return of Brother Petroc.” Written by a Roman Catholic nun, it features an Elizabethan monk, thought dead, who awakens in the 1920’s as his “relics” are about to be moved. Knowing nothing of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation or the bewildering growth of “orders” within the Roman church, he is unprepared for the multiplicity of spiritual “disciplines” he encounters and temporarily loses his sense of God’s presence while trying to adapt himself to new (to him) practices. He is helped back to his formerly peaceful state by a discussion with a priest about mistaking the means for the end.

At the end of this same day, I read your blog post and there is the same theme in your presentation of one of Metropolitan Bloom’s writings. I suspect Someone is trying to tell me something . . .

Thank you for introducing the writings of Metropolitan Anthony. I have also come to the same conclusion as Columbia there are no coincidences in our journey of Orthodoxy discipline. Since Pascha St. Andrew’s “Breastplate Prayer” has been an addition to my morning prayer rule. I simply had no idea why the words of the Breastplate Prayer become so necessary every morning. This post has opened my eyes to the truth of the prayer – unless those around you see Christ in every aspect of our life – discipleship has not been achieved.

So, it seems Someone is trying to tell me something also…