In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, one God. Amen.

Every single person, whether a man, a woman, or a child, has been given by God a deep, primal longing for Him.

We generally go through our days thinking of our desires for other things: I want breakfast. I want to sleep. I want to feel loved. I want some coffee. I want to get through this day. I want to finish this project. I want to buy a house. I want a car that won’t break down. I want to find someone who loves me. I want to be somebody. I want to make a difference. I want to get out of this traffic. I don’t want to die.

But if we really start to think about any one of our desires—pick one, any one—then we will find that they are fundamentally a desire for life. The desire for food is an obvious one, just like the desire not to die. But even our desires for possessions are about desiring life—we think they will help us feel alive, or at least that they won’t get in the way. A car that breaks down restricts my life, but a good car will get me there. Even the desire for accomplishment or love are about our desire for life.

But what is life, anyway? Is it simply to be animated, to be breathing and having our hearts beat rather than to be stilled and lying in a grave? Is it getting everything we want? Is it to “be all you can be”? Is it having a big list of accomplishments? Is it feeling safe, comfortable and secure? Is it even feeling content?

Those things are not life, but they do all point to what life really is.

Let’s think back to that moment when God created mankind: At one point, God took dirt from the earth and fashioned it into a man, into Adam. But Adam did not have life until God did something more than just shaping him. Adam became a living soul when God breathed into him the breath of life (Gen. 2:7). And what is the “breath of life”? It is nothing less than the very presence of God Himself. From the beginning, we were made to breathe God.

So why do we have this longing, this ache for life? Why do we always seem to want more? Why are we driven?

The reason why this desire for life is so driven and can even feel desperate at times is because of what Adam did with this greatest of all gifts given to creation. Yes, it says nowhere in Scripture that when God made animals or plants or rocks or even stars and planets that He breathed into them the breath of life. Only man received the breath of God Himself. So what did Adam do? When he sinned, we could say that in some sense, he exhaled God. He expelled the breath of life.

That is not to say, of course, that he succeeded in getting rid of God entirely from himself. God, in His mercy, remained within Adam enough to continue to keep him essentially alive, moving, thinking, feeling and exercising free will. But all of those functions came to be impaired, and Adam began to die. He also began to sin even more, because his free will had become distorted.

And therefore began the hunger, a hunger that has now lasted for millennia, a hunger that consumes our entire race. We hunger to regain the life that is the breath of God. Life—real life—is actually God. We call Him the “Giver of Life,” and what He gives is Himself, His actual presence. If you have life at all, even incompletely, then you have God within you.

And all of this is why we celebrate the man whom we remember today, on the Second Sunday of Great Lent. This man is called St. Gregory Palamas, and he was the archbishop of Thessalonica in Greece for a number of years in the 14th century, right around the same time that Geoffrey Chaucer was born, the man who wrote The Canterbury Tales.

But before he became an archbishop, Gregory was a monk on the holy mountain of Athos. During his time there and also when he later became an archbishop, Gregory was involved in a controversy that cut straight to the heart of this longing for life that all of us who are sons and daughters of Adam share.

At that time, there was a certain heretic named Barlaam, who was from the southern part of Italy, which was Greek-speaking at the time. Barlaam made the claim that the highest possible knowledge of God that anyone could have was through the mind, that the philosophers knew God better than the prophets and even the apostles.

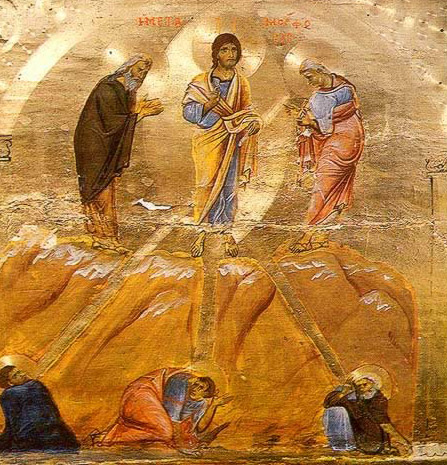

Gregory answered that the human mind, while a great gift from God, was not actually capable of the kind of intimate knowledge and communion that Adam had received from God, that there was something much deeper, that the Christian could actually know God and see Him with the heart, as a light shining in. And indeed, sometimes this heart knowledge of God was so powerful and so pervasive that some people were actually seeing the light of God with their physical eyes.

Isn’t that why we’re here? Don’t we want to see God? Aren’t we here not just to learn about God with our minds, but truly to know Him with our hearts?

If I just study God but never really come to know Him—that is, if I know about Him, but don’t know Him—then am I really experiencing that breath of life? Am I truly alive?

Another of our saints, who lived quite early on in the Church’s life, in the second century in what is now France—Irenaeus of Lyons—wrote that “the glory of God is a man fully alive.” And with that saying, all of the pieces fit together. God’s breath, God’s life, God’s light—these are our experience of God’s glory. When God’s glory truly shines into a man or woman or child, then that person becomes fully alive, because God’s glory is God.

That is what life is, brothers and sisters—it is to have an intimate, personal experience of God’s glory, of God. All the other things we call “life” are really just reminders of our loss of that one thing needful—the glorious, life-giving breath of God.

That’s what salvation is. That’s what the Church is. That’s what Christian life is. That’s what human life is. It is a struggle to overcome our distorted wills, our distorted desires, so that we return to that perfect moment when the Holy Trinity breathed into Adam’s nostrils the breath of life, that moment when the communion with the Creator was perfect.

So how do we do that? In the epistle reading for today, Paul asks us, “How shall we escape if we neglect so great a salvation?” He by no means assumes that you can come here, fulfill a summary “obligation,” and then can say, “Yes, I’ve got the breath of God back.” Salvation is something that can be neglected, and if neglected, we will not escape all that the loss of the life given to Adam really entails—spiritual death, eternal death. Not ceasing to exist—no, for we will all exist forever—but an eternal existence of continual dying, decay and distortion.

But St. Gregory Palamas gives us the key. He earnestly taught that ordinary people, just like you and me, could see the divine light of God, could breathe the breath of God once more, if they will truly give themselves to prayer, to fasting, to worship, to good works, to humility, to real change, to becoming the kind of people concerning whom others can truly say, “Here is one in whom God lives, in whom God breathes. Here is one in whom I see God’s glory.” Are you such a one?

The glory of God is a man fully alive.

To God therefore be all glory, honor and worship, to the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen.

Thank you, Fr., for this beautifully written post! This is the essence of Orthodoxy!

Randi

This is just too good not to share…It’s on my facebook page!

Father bless!

With your approval, I would like to link to this post from my blog.

Library Bob

No one needs anyone’s approval to post links!