Throughout much of January and often into February, I spend close to 20-30 hours every week visiting the homes of parishioners and blessing them as part of the annual Theophany celebrations. I put several hundred miles on my car’s odometer during this time. Aside from the extra workload and of course the joy of visiting parishioners in their homes, I also particularly enjoy driving around the countryside in and near the Lehigh Valley. If I have some extra time, I may wander a bit and follow some rabbit trails that my GPS or simply something catching my eye might take me down. This past Saturday, the sign depicted in the photo above is what quite suddenly caught my attention.

As you no doubt know (especially if you’ve read this), I have a great curiosity for obscure religious groups. I must admit that, though they are perhaps somewhat known to many of my fellow Pennsylvanians, I had never heard of the Schwenkfelders. What could they be? And what was this remote little spot out in the woods with the weathered sign?

After seeing the sign, I pulled over, parked my car, and walked up the hillside in the direction of the sign’s arrow. There, I was greeted by a remarkably picturesque little cemetery. And of course, I find old cemeteries utterly irresistible.

Nearby was a fairly unremarkable building (the meeting house) that looked like a small church whose windows were boarded up and yet curiously seemed to have recently received a fresh coat of paint.

At one end of the meeting house was a stone set into the ground that gave some details of its use just over a century ago.

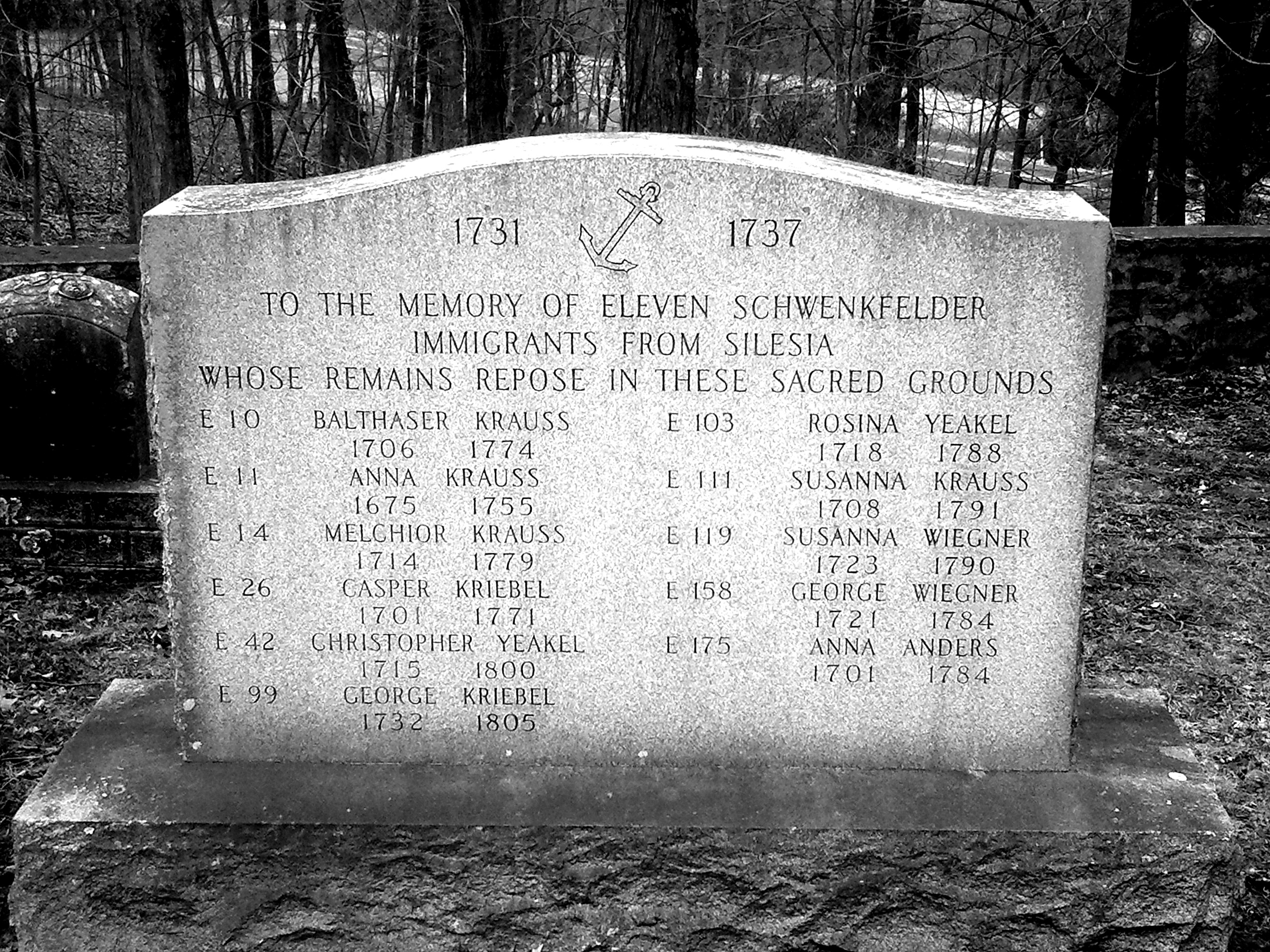

One of the things that fascinated me most about this site was one large memorial stone toward the back of the cemetery that was dedicated to the original Silesian Schwenkfelder immigrants who had come to the area almost 300 years before. The stone is of course interesting for its historical significance, but what particularly delighted my eye was to see that three of these eleven Schwenkfelders in fact bore the traditional names of the Three Wise Men who came from Persia to visit the child Jesus after His birth: Melchior, Casper and Balthaser (the latter two are most often spelled in English as Caspar and Balthazar).

It seems curiously coincidental that all three Magi would be represented among these folks, but perhaps there is a tradition among the the Schwenkfelders of using these names, if only because their namesake, Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig, bore one of them.

So who are these people? You can of course read about them on Wikipedia or at the website of the Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center, not to mention the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia (which often has rather droll entries for non-Roman Catholic religious entities), and there are of course whole books dedicated to these folks. But here’s the brief version of their story:

Caspar Schwenckfeld (ca. 1489 – 1561) himself was a Radical Reformation theologian in Silesia, having had a conversion experience when he was about 30, joining the Lutheran church. He eventually came to disagree on the sacramental reality of Holy Communion contra Luther and also held some rather odd Christological views (namely, that Jesus’ humanity was indeed real but was not consubstantial with Adam’s seed but represented a new creation, derived from His divinity). He broke from the Lutherans and gathered a small group of followers, who over the years were persecuted by the Lutheran state church.

About 1,500 Schwenkfelders still persisted at the opening of the 18th century, and they fled Austrian imperial persecution in Silesia, many finding refuge with the famous Count Zinzendorf, who is perhaps more notable for his connection with the Moravians (he later came to America and actually preached right here in Emmaus). In the 1730s, a number of Schwenkfelders immigrated to the Philadelphia area, forming a Society of Schwenkfelders some fifty years later. They did not form an actual denominational body until 1909, by which time the Schwenkfelder community in Europe had become extinct. There are now only five Schwenkfelder churches in the world, and they are all within fifty miles of Philadelphia. It does not seem that they explicitly retain a common theology based on Schwenckfeld’s teachings but have become essentially congregationalist in that regard.

During my wandering on Saturday, I also found the new location of the old Kraussdale Schwenkfelders in Palm, Pennsylvania (a whimsically named town, considering our climate). It looks little different from most of the Lutheran churches in our area.

A mystery still remains for me, though, and that is how these Wise Men of Silesia came to bear these remarkably uncommon names in common with those ancient Persian magi. Perhaps that will be the occasion of a future visit to the aforesaid library.

What I find interesting is that of the 209 graves at Kraussdale Schwenkfelder, 70 if them belong to the Kraus family – and at Palm, there are only 2 Kraus graves. The Kriebel family has 23 graves at Kraussdale and 8 at Palm. Makes you wonder what happened to all the Krauses. There are also 22 tombstones that can’t be read because of age. Wonder who they are. And of all the tombstones that can be read from both cemeteries, they are the only magi in the lot of 335 graves. Curiouser and curiouser as Alice would say.

My guess is that the community simply diversified, but the original families kept filling up the old plots even after the new cemetery was established. There’s a Krauss buried at Kraussdale as late as 1957, 46 years after the old meeting house had been shut down.

Also, I suspect that the listing for the Palm cemetery is decidedly incomplete. Find-a-Grave has only 126 listings there, but I was there on Saturday, and there were far, far more than that, which you can even see from the photos on the site. I would be willing to bet that the old cemetery (which is much smaller than the new one), the subject of far more historical interest, is simply much better documented on the site.

You will find Krausses and Kriebels buried nearby in the cemetery at St Paul’s Lutheran Church in Red Hill, like my great grandparents and grandmother. Some of the Kraussdale Schwenkfelder descendants stayed in that region but at some point converted, for whatever reason.

Father Bless,

You say you love old graveyards. Did you ever do gravestone rubbings (superimposing old gravestone writings and engravings using parchment paper and charcoal)?

Nope.

A friend emailed me a link to your blog a few months ago… been reading it since. I love reading your blog. Very awe inspired and simply a delight to read.

Thank you!

What a fascinating article. Reading through, and looking at the photos, before you got to your research findings, I thought, “I bet this is a Radical Reformation offshoot. It looks just like some of the old Mennonite churches/cemeteries I’ve visited.” Sure enough. Not Mennonite (my background), but still from that era. Thanks for posting this little window into your corner of the world.

I’m quite fond of visiting old cemeteries. Why I’ve been known to bring along finger sandwiches and tea, and spread out a blanket on the lawn. After ingesting said delicacies, the sobering task of reading epitaphs begins, in which one can uncover all sorts of information leading to various connections among the dead buried there. Such visits can impel one to meditate on the mortality of all human flesh, which can then lead to rejoicing in the resurrection of Christ. O death, where is thy victory? O death, where is thy sting?

Morning Father Stephen,

I am a German Baptist Brethren church historian. The site above is one of several sites I maintain for accumulating and disseminating the history of that religious body.

Presently I am working on taking historically interesting articles from various almanacs, annuals and yearbooks dating from the 1870’s onward, placing them into a book for later publication.

One of these articles is one concerning the “The Swenkfelders” originally printed in 1880. Wanting to include any possible photographs I did a search of the Internet, eventually coming to your blog. Interesting, and I concur with your observation about old cemeteries; they can be extremely dangerous if you have the history bug.

If you wish to include it, the majority of the Swenkfelders arrived on the ship “St. Andrew” on Sept. 12, 1734. The Krebiel family is on board, the Krauss family is not. The ship “Hope” of Sept. 23, 1734, the ship immediately after the “St. Andrew” contains Johann Wilhelm Krasz, aged 48; his wife Sophia Margret Krasz, 36; and their children, Johan Caspar, 11; and Johan Philip, 3½. I am not stating that this Krasz family is the Krauss family; only that it is a possibility.

I am looking to make a trade, my article as from the original for a selection of color renditions of your photographs. I will likely use only one, but I like to have a selection to chose from.

Cordially,

A. Wayne Webb

I’m not sure I understand what you mean to trade. You want republish one of my photos in a book? And what do you mean when you say you want to trade your article? (An article you wrote? If it’s a historical piece from the 1880s, it’s in the public domain.) That I get to read it? (I’m not planning on publishing about the Schwenkfelders.)

Please forgive me if I am a bit dense here.