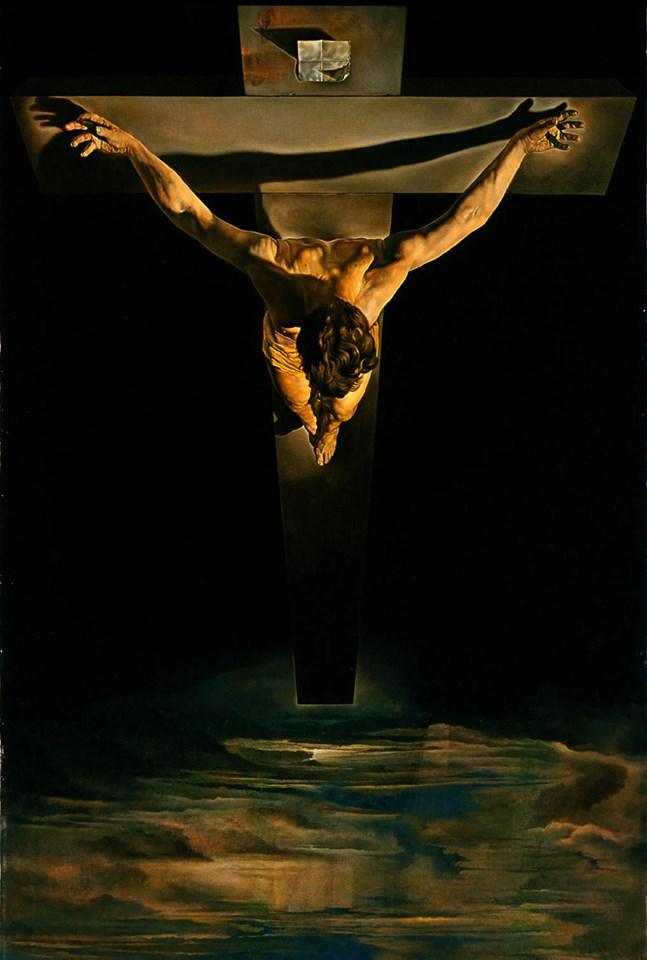

The major themes of Tom Holland’s newest book of history, Dominion, are exemplified by the differing presentation of the book in the United States as opposed to Holland’s native Britain. The British edition of the book is Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. The cover features the head of a Corinthian pillar with an inverted modern skyscraper above. The American release, on the other hand, is entitled: Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. Its cover is graced by Salvador Dali’s “Christ of St. John of the Cross”, a depiction of Christ crucified over a misty and chaotic world, if not before its very foundations.

The contents of the book in both cases and Holland’s argument are the same. The difference in presentation, then, expresses a difference in the audience of readers and how congenial they might be expected to be toward his message. Dominion is a work of cultural history, not church history, but it communicates that the history of the culture of the European West and its former colonies cannot be disentangled from Christianity and its central teachings.

The contents of the book in both cases and Holland’s argument are the same. The difference in presentation, then, expresses a difference in the audience of readers and how congenial they might be expected to be toward his message. Dominion is a work of cultural history, not church history, but it communicates that the history of the culture of the European West and its former colonies cannot be disentangled from Christianity and its central teachings.

Dominion grew out of an essay by Holland published by the New Statesman in 2016 which itself expressed the beginnings of Holland’s reappraisal of Christianity. Most of Holland’s published work surrounds antiquity and, in particular, its empires. In the essay and the subsequent book, Holland describes his childhood love of dinosaurs which ultimately led to his abandonment of the faith of his youth. His later love of the classical world he sees as closely related.

The likes of Caesar, Augustus, and Xerxes are super predators on par with any Tyrannosaurus Rex. These are men who boasted publicly of having killed and enslaved thousands. These are men who viewed themselves as so superior to the common run of humanity that their only real kin were the gods. These are men who found the poor, the weak, the sick, the humble to be pathetic filth more akin to animals than to themselves. While Holland was not then and is not now a Christian in religious belief, he has discovered that his own moral sense has little to do with that of the classical world and everything to do with the moral teachings of Christianity.

This new book explores that initial insight. Holland begins in familiar territory, the Persian wars, and describes the classical world in all of its bestial glory before moving on to the world of Judaism and thence entering into the era of Christianity. In regard to Judaism in particular in the Second Temple period, Holland adopts for the purposes of his argument the commonly held views of critical historians. These include the Persian origin of many elements of Judaism, ancient Israel’s early polytheism from which monotheism later evolved, and that at least the early history of the Old Testament is entirely myth in the sense of fiction.

As a non-believer, these are undoubtedly Holland’s actual positions, but even were they not, there would be little sense in contesting them here. The arguments involved would constitute other books entirely. More directly, however, Holland’s argument is directed toward a general audience and not to Christians only. He aims to correct the record of Western history on several counts and to demonstrate that even those who consider themselves most secular in our contemporary cultural moment are, in fact, Christian in their bones. Our atheists are Christian atheists.

Holland’s strength as a writer has always been centered in his abilities as a storyteller. His approach in Dominion proceeds from this strength. In a sequence of eras beginning in the fifth century BC, Holland selects figures and tells their stories in parallel. In the fifth century AD, this is Ss. Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, and Macrina, Martin of Tours, Paulinus of Nola, and Augustine. In the thirteenth century, it is Elizabeth of Hungary, Conrad of Marburg, and Thomas Aquinas. In the early part of the twentieth century, it is three men who fought at the Battle of the Somme in 1916—Otto Dix, Adolf Hitler, and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Holland traces his themes from classical Greece to the present cultural moment. He finds these themes not only within a given era in the stories of people from varied lands and languages but also stretching across eras and giving shape to the formation and reformation of Western culture. In an interview, Holland described the writings of St. Paul as like a depth charge, the shockwaves of which pulse and ripple outward through the centuries.

Dominion is not, as already indicated, a work of church history. It is not a book aimed at tracking the development of theology or of particular church institutions in the West. Rather, it traces the interplay of Christian teaching and culture which has resulted, over two millennia, in a profound transformation of culture. This transformation is apparent both to the extreme counter-cultural nature of Christianity’s proclamation in the Roman world, the datum which originally inspired Holland’s reflection, but no less so in the works of Nietzsche as but one modern example.

Nietzsche had a profound understanding of the nature of Christian teaching and the way in which it had completely upended the preceding worldview of the classical world. He understood it and he hated it. He further foresaw the consequences that would come when Western culture finally decided to divest itself of Christian moral teaching and the worldview whose underpinnings it had already rejected at an intellectual level. These consequences were reaped in blood throughout the twentieth century and, should de-Christianization prove successful in the future, they can only continue and intensify.

The truth, however, as Holland shows, is that the de-Christianizers have not been that successful at all. Atheists attack the Scriptures and Christian history as immoral when compared to the standards of Christian morality. They do not do this to undermine the consistency of the Christian worldview from the outside but rather because they still share that morality which found its origins in Christian teaching.

Same-sex marriage advocates reject Christian moral teachings regarding the propriety of sexual relationships but firmly embrace a vision of loving monogamous marriage which is itself purely the product of that same teaching. Pro-choice activists argue for the right of women to control their own bodies, which dignity found its origin in Christian teaching that women, as well as men, are formed in the image of God and of equal value.

The very idea that women have a right of consent in sexual matters grew from the beginnings of Christian monasticism. Christian leaders had to transform a culture in which women belonged to their fathers until given by that father to a husband to allow that a woman could choose not to be married, to remain chaste if she so desired in order to devote herself and her life to Christ. The culture wars are, in Holland’s argument, an inter-Christian conflict between those who wish to maintain Christian tradition as a historic whole and those who wish to sacrifice or transform some elements while retaining others intact.

The greatest contribution of Holland’s book likely stems from his intimate familiarity with the ancient world. This allows him to present Christianity in a form much closer to the state in which it originally existed, rather than as “a religion”. In fact, he traces the development of the idea of the secular from St. Augustine’s struggle to understand the events of his own age within the context of his Christianity. He further describes the emergence of the concept of “religion” and its radical transformation over time to its present understanding.

With these later developments peeled back, Christianity emerges as a system of interacting with understanding the world, described in teachings and lived by the actual human persons of every era. This way of thinking and seeing has been bred into the bones of every person born in the West for centuries, though today it may go unnoticed like the air which we breathe. Holland’s mapping of the road from the ancient world to the present moment illuminates the latter and explains it. It also provides a map, for those so inclined, to walk back through the intervening eras and arrive at Christianity’s core at the moment of its ancient birth.

Very interesting stuff. I had a conversation with an older Protestant missionary at L’Abri Fellowship this morning. He spent most of his career in Eastern Europe, including smuggling Bibles into the Soviet Bloc, & we were talking about why he believes the faith is true. He said that at base there a whole range of ways in which humans function, including morality, epistemology & much more, which only fit with there being an ‘infinite, personal God’, & everyone, atheist or not, acts as though those things are true, whether their worldview goes on to uphold or deny that fact. Your post really reminded me of this.

I have been saying these things myself for some time. Atheists have to use, absolutely have to, Christian morality, a Christian view of man, to ultimately negate the means to being a Christian.

I have from time to time expressed my frustration over the MeToo movement to my Christian grandmother. She couldn’t help but think I was not on the side of those who were mistreated. But my comments boiled down to this, and it may seem crude at first but only if you don’t think about it, “the women in the MeToo movement, who, at least as celebrities go and the people who make news, are by and large unbelievers. If they want to complain they need to do so as Christians.”

When there are those in the MeToo movement who are either atheists or practical atheists as well, the irrationality only gets worse. Unless it’s actually wrong, unless there is an inherent dignity in a person to uphold – which there is not when mosquitoes have as much a claim on life as we do in their world – stop complaining, this is the world you believe in. Now, part of my saying this is to get a reaction. I, as a Christian, of course I believe mistreating anyone is wrong and evil, but I have a basis for believing as such. When someone else is openly against a Christian view of the world whether by deduction (their life in the news shows this) or their open statement and they want treatment that is completely reliant on a Christian view of man – well, sorry.

But, Fr Damick, this is why we should be pointing out, as this author does it appears, that most people are not atheists, they are heretics. Same sex marriage is heresy not liberalism. No fault divorce is heresy not progress. Happiness as an ultimate goal on planet earth is heresy not _________. And we should state it this way precisely because it is a distortion of the already Christian view of man the heresy depends on – because all of it starts with an anthropology that is inherently Christian even if distorted.

For an Orthodox Christian for example to endorse SSM – they appeal to the fact that the Fathers never brought this stuff up because it was not a reality to address. Or they say that we should re-engage the Fathers and the Tradition to see if there is room for monogamous SS pairings because they didn’t dogmatize morality. They’re getting out ahead of the argument they know is coming by stating in advance their view isn’t heresy, as if that was enough to avoid the charge. But all along, the inherent lie is that there is an insatiable, necessary need in a person to achieve happiness or homeostasis achievable only in a SSM. The same would be true about any so called need whether hetero or not. It’s just not true according to Christian anthropology since we are to acquire selfless love for God not selfish love for another. In short, though there would be an argument to sustain, this is the root of it. To embrace a SS relationship, with all the prohibition, but then to negotiate with Tradition and the Scriptures on the basis of selfishness in the end – is against our anthropology even though it’s also based on it – so, it’s heresy.

And to be honest, I think this would possibly take the sting out of Christian opposition to SS whatever. It’s more of a concern for the potentiality of a human, the upholding of their dignity to oppose whatever would prevent you from becoming who you are meant to be. But since they believe their highest end is happiness we just want to kill their enjoyment of life. Theosis is man’s end and Christian anthropology is built on this. Happiness is not the telos for man, theosis is – if we made this clear, we might make some sense.

God bless you Father,

Matthew Lyon

Thanks for the comment. I didn’t write this article, however.

I detect a bit of Van Tilianism here.