Editor’s Note: This article is part of an October 2017 series of posts on the Reformation and Protestantism written by O&H authors and guest writers marking the 500th anniversary of the nailing of Martin Luther’s 95 theses to the church door at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. Articles are written by Orthodox Christians and discuss not just the Reformation as a historical event but also the spiritual heritage that descended from it.

As followers of this blog are likely already aware, October 31 will mark the five-hundredth anniversary of the day Martin Luther reputedly nailed his ninety-five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg.

As momentous as the milestone is, however, it’s hardly the first of its kind. Lutherans have been observing centenaries of the Reformation for, literally, centuries.

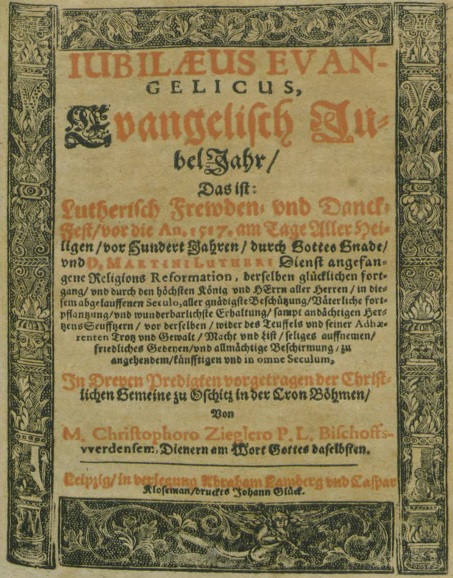

The first of these celebrations dates to 1617, when prominent Lutheran pastors and theologians declared a commemorative “jubilee year” (Jubeljahr) to pay tribute to the start of the Reformation.

From Friday, October 31, 1617 (the eve of All Saints’ Day), through Sunday, November 2, 1617, Lutherans across the Holy Roman Empire marked the historic anniversary with church services, thanksgiving, and (above all) lengthy commemorative sermons that, along with being preached in real-time, would be distributed in printed form over the course of the coming months. These sermons typically narrated stories from Luther’s life, memorialized the inception of his teachings, and encouraged listeners to give thanks to God for the flowering of the Reformation over the previous century.

Photo credit: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt Digital Collections.

Thus, the first Reformation jubilee was not intended as merely a historical exercise but also a spiritual one. It was to be observed with “devotion and discipline,” honoring the events of 1517 because “in the same [year], the precious […] blood of Jesus Christ and the grace of God was distributed for all places and all times through Luther’s faithful service, and the golden gates of heaven were reopened for every man.”1

Upon learning of the Reformation “jubilee year” of 1617, modern readers will be quick to recall the command given by God to the tribes of ancient Israel to “hallow the fiftieth year and […] proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you: you shall return, every one of you, to your property and every one of you to your family” (Lev 25:10).

Although Levitical jubilees ended when the Israelites were exiled, they nonetheless persisted in the Christian imagination as a metaphor for salvation and redemption. Lutherans capitalized on this in declaring 1617 a jubilee year. For them, the mercy God exhibited through Martin Luther was at least as great a miracle as the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (which—according to one pastor’s estimate—had occurred “2454 years before 1517 years after Christ’s birth”).2 After all, the Hebrews had suffered under the Egyptians for less than 150 years, whereas the Gospel had been oppressed by the popes of Rome for many centuries.3 In 1517, however, God had finally seen fit to pour forth His Gospel once again. And just as Christ had entered the world in the unassuming town of Bethlehem, God appointed the humble little hovel of Wittenberg, His “white mountain” (weisse Berg), for His Reformation.4 Through the loyal servant Martin Luther, God let His light shine from the mountain of Zion.5 By juxtaposing the Reformation against the restoration of God’s chosen people in the promised land, early seventeenth-century Lutherans used the concept of a jubilee as a means of locating themselves within the long arc of salvific history.

At the same time, however, the Levitical jubilee was not the only one Lutherans were thinking about when 1617 rolled around. Perhaps more than anything else, the Reformation jubilee was an effort on the part of Lutherans to distinguish themselves from Roman Catholics, who had been observing their own jubilee years for over two centuries.

On the feast of the chair of St. Peter (22 February) 1300, in response to large numbers of pilgrims swarming Rome to honor the start of the new century, Pope Boniface VIII issued a bull announcing that plenary indulgence would be granted to any of the faithful who visited the holy city and performed a prescribed set of observances during the remainder of the year. In addition to a thorough confession of sins, these included visiting the four major churches of Rome every day for fifteen consecutive days. Although the pope did not explicitly refer to this year as a jubilee, its salvific implications were not missed on his contemporaries, who quickly began referring to the indulgence year as a jubilee. In an explanatory note accompanying the bull, Pope Boniface decreed that a similar indulgence festival be held every one hundred years in the future. Over the fourteenth century, however, subsequent popes shortened the intervening years from one hundred to fifty, then to thirty (approximating the duration of Christ’s earthly lifespan), and finally to twenty-five years.

Before 1617, the most recent Catholic jubilee had taken place in 1600, provoking criticism from several Lutheran theologians. Foremost among them was Augsburg pastor Bartholomäus Rülich, who (among other things) disparaged papal jubilees for contradicting the spirit of Christ and for simply lasting for too long—far longer than any other Christian feast.6

Rülich and his likeminded contemporaries saw Catholic jubilees as microcosms of the excesses and corruption of papalism.

Rülich and his likeminded contemporaries saw Catholic jubilees as microcosms of the excesses and corruption of papalism.

Perhaps the biggest problem with Catholic expressions of the jubilee, as Rülich saw things, was that by offering plenary indulgence to pilgrims, the pope made his jubilee out to be the acceptable time of salvation (see 2 Cor 6:2). Yet salvation cannot be bound to a specific time. “During whatever time of year repentance and forgiveness of sins are preached in [Christ’s] name,” Rülich wrote in his treatise, “there is at the same time remission of guilt and anguish for all those who believe in it. Of what necessity, then, is a special year?”7

If Catholics must have a jubilee, Rülich reasoned, its timing should at least be adjusted to make it more Christocentric. On this matter, Rülich was gracious enough to offer a handful of helpful suggestions to his Catholic counterparts. Among other things, Rülich recommended Catholics hold their jubilees every thirty-one years, recollecting Christ’s age when He began His earthly ministry and proclaimed the year of the Lord. In that scenario, however, the jubilee should last not one year but four, since that was the maximum length Christ’s ministry could have lasted before He was crucified.

Most of all, Rülich was adamant that jubilees should be just plain shorter. After all, the feast days that commemorate the most basic articles of Christian faith (which, for Rülich, boiled down to Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost) were celebrated for only one or three days, while papal jubilees—a wholly unnecessary if not outright dangerous holiday—lasted an entire year.

Perhaps it was in view of this temporal excess that, seventeen years later, led Lutherans to restrict their own jubilee year to just three days—October 31 through November 2.

Whatever the case, they also avoided excess on other fronts. Instead of commemorating the Reformation through liturgical pageantry like processions and pilgrimages, Lutherans emphasized the importance of sermons, using the anniversary to proclaim the Gospel in and through the historical lens of the Reformation. By elevating the place of the salvation message in their celebrations, they hoped to assuage God’s wrath:

If we don’t hold our jubilee year with great discipline and devotion (which we daily undertake inasmuch as the teaching of the merciful forgiveness of sins through Jesus Christ is proclaimed loud and clear) God will send us a Eiuleum, that is, a year of lamentation (Heuljahr).8

As October 31 approached in 1617, Lutherans—ever-mindful of the possibility of God’s judgment—were careful to distinguish their own, godly jubilee from the false jubilees proclaimed by the “Antichrist’s [i.e. pope’s] synagogue.” In their eyes, the Catholics celebrated their jubilee years with the “highest pomp and pageantry” and fed the poor with empty promises, giving them nothing to leave Rome with other than “ripped clothing and bad consciences.”9 For Lutherans, however, the Reformation jubilee was a source of hope and thanksgiving, drawing their gaze past this earthly veil of tears and toward the “the eternal, perpetual jubilee […] in the heavenly chamber of joys (Frewdensahl).”10

To recall the start of the Reformation was to recall the presence of God in time and history, a pivotal juncture when God mercifully manifested the Gospel anew and ushered in an era of redemption for faithful believers. People living at the start of the Reformation could not have known how “it would progress […] in the following times.” Through the aid of hindsight, however, Luther’s descendants in 1617 could perceive “the beginning, middle, and end of the Gospel’s course in this last 100 years.”11 The first century of the Reformation thus constituted a “year of the Lord,” an epoch of “blessed time.”12

Staking out a place for themselves in the teeming current of salvific history—and asserting that place over and against the Catholics—allowed Lutherans of the early seventeenth century to affirm their identity at a time when confessional tensions across Europe had reached an all-time high. Coincidentally, the centenary of the Reformation occurred less than a year before the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) erupted, a disastrous religiopolitical conflict fought largely (though not exclusively) along confessional lines.

Looking back, it’s possible to regard the 1617 jubilee as a kind of last hurrah for the Lutherans before the outbreak of a war that would leave precious little optimism or religious jubilation untouched. By the time that war was concluded—which itself required the most painstaking and convoluted peacemaking process Europe had ever witnessed—it killed more people per capita than any war ever fought on the soil of present-day Germany, past or present (yes, that includes the world wars).

Still, for three days in 1617, Lutherans could gather to honor the scourge of papalism God had rescued them from, the deserts and valleys and Thuringian forests He had guided His Gospel through to get it into the minds and hearts of His people. And in their own, temporally bound jubilee, they could learn to turn their gaze to the larger, grander jubilee year of eternal life, a jubilee that (especially for the roughly thirty percent of the German population that would die as a result of the three decades of war to come) would begin sooner rather than later.

- Christoph Ziegler, Iubilaeus Evangelicus (Leipzig: Lamberg et. al., 1617). All translations mine.

- Georg Zeämann, Drey Evangelische Jubel- Und Danckpredigen (Kempten: Krauser, 1618), 37–38.

- Ibid.

- Zeämann, ibid., 75–76.

- C. Dieterich, Zwo Ulmische Jubel und Danckpredigten (Ulm: Meder, 1618), 1–2.

- Bartholomaeus Rülich, Christlicher Gegenbericht von dem bäpstischen Römischen JubelJar und Ablaß (Frankfurt: Saur, 1600), 19.

- Ibid., 75.

- Zeämann, ibid., 94. The word Eiuleum, a pun of Zeämann’s making, combines the Latin words eiulatio (shrieking or lamenting) and iubilaeum (jubilee)—elsewhere, he uses it to refer to Catholic jubilee years (ibid., 8).

- Ibid.

- Dieterich, ibid., Aivv.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Interesting post. I was not aware of the Jubilee celebrations and the method of celebrations does leave one with questions. I do find the “history” that the Reformers were referring to as a curious distortion of the actual events. I wonder just how they determined it.