Folks,

This is a response to a long and interesting comment by ‘Prometheus’, a frequent visitor to the OrthodoxBridge. Part I contains Prometheus’ comment and Part II my response.

I underscored parts of Prometheus’ lengthy comment as a way of assisting the reader.

Robert

Part I. Prometheus wrote:

Robert,

Your thoughts are pertinent as ever, but this hermeneutical problem is not limited to Protestantism. When Orthodoxy faces crises, it has not always been clear which side one should stand on. During the controversy over Arianism, the process was not simple nor immediate. But the church trusted God to lead them the right way, even if there was a lot of disagreement. At some point what became the recognized church excommunicated those who at the time still thought they were the true church. So, “in the moment” so to speak, it doesn’t seem that Orthodoxy gives any clear stability when there is a crisis. The problem with Apostolic succession, too, is that when there is a crisis, there is not agreement as to what constitutes Apostolic succession. Then one resorts to consensus . . . and the church as a whole has to accept the decision of the fathers (i.e. the priesthood of all believers is involved). All this seems much messier than you make it out to be. Your faith, then, seems to be not in the Orthodox tradition being less messy, but in the Orthodox church itself. This same type of faith is fairly true about those in Protestantism who have not examined their presuppositions . . . they trust in the Bible itself (or, less critically, in their denomination). While I know that the Orthodox don’t see the Orthodox-Oriental split in the same light, nor the East-West schism, I would submit that these are the types of denominational splits that predate Protestantism. For someone who would like something more solid than the current fragmentation of Protestantism, I think it is great to look back at history . . . but it keeps throwing the same kinds of problems at us that we are trying to avoid: disagreement, disunity, and schism. Certainly a conscious pursuit of ‘tradition’ has helped keep these groups from fracturing nearly as much as Protestantism, but it hasn’t kept it from happening altogether . . . and some of us find ourselves scratching our heads still and saying, “how do we know which is the true church.” I would also like to add that at least on the literalistic level, the Bible contains books that are like any other. They can be read and understood without a controlling body of tradition. We believe that Shakespeare wrote intelligible plays and that they can be read with more intelligence when we know the background of their writing. But we don’t confuse that with the need for an “official” tradition to interpret Shakespeare for us. Certainly there will be varieties of interpretation . . . but that doesn’t mean that each variety is equally valid. Some people will have down-right wacko interpretations. Again, that doesn’t undermine the validity of a better interpretation, nor does it even give us the need for a special interpretive tradition. But even if we grant that there is a good interpretive tradition for Shakespeare, that doesn’t mean all of its individual interpretations are correct. The good use of interpretive tradition in literature includes an ability to critique that tradition when it butts up against the literature or other information we can gather from the time period. What the Orthodox and Catholic churches have, is a tradition that resists change, but that cannot itself be corrected. Now this is all fine if they are true. But if they resist correction by data inasmuch as they may have been distorted from original tradition (compare how the Bible’s manuscripts have come down to us with variations and how in that sense they are distorted; what is the likelihood that the Church’s tradition hasn’t had that kind of distortion as well?), then there are serious problems. The problem with Protestant traditions is that they tend to deny that they are traditions and then impose themselves very rigidly on people (e.g. there is a sense in which sola scriptura is at odds with the other solas because the others limit our ability to critique them using sola scriptura; logically, then, you could say you believe in sola scriptura but deny what scripture teaches because you have an a priori commitment to sola fide or some such).

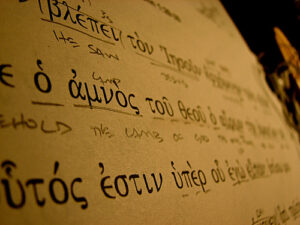

I say all this knowing that there are some seriously good reasons to doubt the doctrine of sola scriptura, and that Christ did speak about revealing truth to his disciples. But I still don’t see how Orthodoxy can escape some of these critiques . . . in addition, I don’t want to have to affirm anything that, for one who spends a lot of time in the Greek text of the New Testament, directly contradicts what is said therein. Sorry if this is not helpful, I just am looking for a way to resolve my own doubts regarding the unity of the early church.

Prometheus

Part II. My Response to Prometheus:

Prometheus,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment. Rather than respond with another long comment, I think it would be better if I wrote a response article. I titled this article “Out of the Frying Pan into the Fire?” because the basic question you posed in your comment comes down to whether the same problems in Protestantism – disagreement, disunity, and schism — can likewise be found in Orthodoxy.

“Without a Controlling Body of Tradition”

Your attempt to liken the Bible to the works of William Shakespeare while interesting doesn’t touch upon the central problem of hermeneutics. The greatest controversy over Shakespeare’s works has more to do with authorship than with how to interpret his plays. I would agree with you that as a literary work the Bible is accessible to the intelligent reader and does not require a key to decode its message. But you overstate your position when you say that Scripture can be understood “without a controlling body of tradition.”

This would be akin to saying that one can read and understand the US Constitution apart from the entity called the United States of America or apart from the decisions rendered by the Supreme Court. Hypothetically, a group of Africans or Asians could find the US Constitution inspiring and organize their particular village along the lines of the Constitution but this would be farthest thing than what the Founding Fathers had in mind when they drafted it! There is currently a controversy between the originalist and the progressive readings of the First Amendment establishment clause. As it became problematic to assert that the Founding Fathers had intended a church-state separation (the originalist approach), separationists find themselves resorting to a progressive/evolutionary reading of the Constitution, i.e., to read the First Amendment in light of the Founding Fathers’ “progressively evolving intentions” (see Grenda). The most salient or most critical question here is whether the Bible is just a human document like the US Constitution subject to changing circumstances or divinely inspired as has been recognized by the Church.

This would be akin to saying that one can read and understand the US Constitution apart from the entity called the United States of America or apart from the decisions rendered by the Supreme Court. Hypothetically, a group of Africans or Asians could find the US Constitution inspiring and organize their particular village along the lines of the Constitution but this would be farthest thing than what the Founding Fathers had in mind when they drafted it! There is currently a controversy between the originalist and the progressive readings of the First Amendment establishment clause. As it became problematic to assert that the Founding Fathers had intended a church-state separation (the originalist approach), separationists find themselves resorting to a progressive/evolutionary reading of the Constitution, i.e., to read the First Amendment in light of the Founding Fathers’ “progressively evolving intentions” (see Grenda). The most salient or most critical question here is whether the Bible is just a human document like the US Constitution subject to changing circumstances or divinely inspired as has been recognized by the Church.

When you used the phrase “without a controlling body of tradition,” you seem to imply that the Bible can be read apart from the Qahal/Ecclesia (assembly of the faithful). This could lead to anachronistic views, e.g., the Gospels written as modern biography or Genesis and Exodus were written as scientific history. Divorcing these biblical books from their social and ecclesial contexts leads to all sorts of difficulties. For example, the creation account in Genesis becomes susceptible to a dogmatic literal six 24 hour day interpretation. Also, the Gospels then become subject to modern historiography that supposedly underlie the quest for the historical Jesus. So are you sure you want to divorce Scripture from the ecclesial context as you imply with the statement that Scripture can be read apart from “a controlling body of tradition”?

Let me ask an empirical question: Did there exist in the early Church a “controlling body of tradition”? The answer is: Yes. The early Church had the Regula Fidei (Rule of Faith) – a shared set of beliefs and metanarrative about Jesus Christ and the redemption of the cosmos. If you are interested, there is Paul Blowers’ article “The Regula Fidei and the Narrative Character of Early Christian Faith” in which he discussed the complex character of the Regula Fidei among the early Christians. The article is nuanced and sophisticated in its use of early Christian sources and its interaction with modern scholars like N.T. Wright. I urge you to read it and learn more about the “controlling body of tradition” in the early Church. The only criticism I have of Blowers’ article is that he overlooked or neglected the critical role played by early liturgical worship in the telling and transmission of the Regula Fidei. The Regula Fidei was more than a set of teachings, it was also a set of practices: liturgical worship, Eucharist, Baptism, and baptismal creeds. The Regula Fidei was lived out through the worship life of the church Sunday by Sunday. The early Christians received it as part of a tradition received from the Apostles, not something excavated from the Biblical text. Scripture was part of a received tradition and interpreted from the standpoint of that received tradition.

Let me ask you a normative question: Is there a need for a “controlling body of tradition”? If the Scriptures were written as a covenant document, then the answer is: Yes. Jesus’ claim to being the Messiah, his instituting the Lord’s Supper and his Great Commission all point to covenant language. The Bible is binding not just because it’s inspired by the Holy Spirit but also because it is a covenant document written under the authority of the suzerain for a covenant community. Genesis and Exodus were patterned after the suzerain treaties of the ancient Near East. Similarly, the prophetic books written by Isaiah and Jeremiah would be incomprehensible unless one knew of the covenant obligations set forth in Exodus and Deuteronomy. Now if there exist a covenant and a covenant people, then there must be a established authority structure for the interpretation of the covenant document (Scripture). You seem to imply that there is no need for a covenant leadership structure for the reading of Scripture. It would be like saying a non-American can read and adequately understand the US Constitution just as much as an American citizen. It would be like a law professor telling his students they could if they pleased ignore the rulings of the Supreme Court. Is that what you are trying to say? I hope not. But if you do agree with my position that the Bible must be read as a covenant document meant to frame and guide life in a covenant community then we must ask: Where is that covenant community is to be found? This leads to your questions as to whether Orthodoxy is all that different from Protestantism.

Non-Historic Churches versus Historic Churches

The main point I wanted to put across in “Deja Vu All Over Again” was that Protestantism is especially prone to conflicting interpretations and to church splits. This is not to say there were no divisions or different theologies among the early Christians but that there is a distinctly different quality about Protestantism in comparison with the historic Christian churches: Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, and the Oriental Orthodox churches.

Historic Churches

There are two types of churches: (1) historic churches that can trace their histories back to the original Apostles and (2) non-historic churches that have no direct ties to the original Apostles. For example, among the historic churches there are three major options: Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholicism, and Oriental Orthodox. The Antiochian Orthodox claims to have roots going back to Acts 11. Roman Catholicism claims that St. Peter founded the church in Rome. And the Coptic Orthodox Church claims that the Evangelist Mark founded the church in Egypt in AD 55.

It is a sad fact that these churches are no longer in communion with each other. Thus, if the new convert were to decide which church to make their home, they would need to examine some basic issues. With respect to the difference between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism one key issue is the Pope’s claim to a universal authority over all Christians and his claim to infallibility. With respect to Orthodoxy one would have to look at Orthodoxy’s claim to have preserved the Apostolic Faith intact over the past two millennia. With respect to the Oriental Orthodox one would need to decide whether or not the Oriental Orthodox were right in rejecting the Christological definitions put forward at the Fourth Ecumenical Council and by Pope Leo in his Tome. Also, one must reckon with the fact that Oriental Orthodoxy has a very small presence in the US and Europe compared with Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

A modern day inquirer who reads extensively might raise the issue of lesser known groups like the Old Believers who separated from the Russian Orthodox Church or the Sedevacantists or Old Catholics who separated from the Roman Catholic Church. In addition, there are Celtic Catholic churches and Celtic Evangelical churches. From a practical standpoint these groups are miniscule splinter groups.

If someone were to ask me how to find the true Church, I would answer: Start with the Book of Acts then follow the historical evidence that leads to where the Church is today. Following the Apostles and their generation of disciples we find the Apostolic Fathers like Clement of Rome, Polycarp, Ignatius of Antioch, and the book The Didache. Then a little later we find the Apologists: Athenagoras, Justin Martyr, Diognetus, Tertullian, etc. By the time of 200s and 300s we come across the more well known Church Fathers: Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, John Chrysostom, Augustine of Hippo, et al. From the fourth to the sixth centuries we encounter the Ecumenical Councils. The task of the inquirer is to sift through the complex interweaving strands of debates, theological terms, and personalities and discern which particular group held fast to the Apostolic Faith. In addition to the primary sources one can make use of J.N.D. Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines, Jaroslav Pelikan’s five volume The Christian Doctrine, and a church history text like Willison Walker’s A History of the Christian Church.

If this seems all too overwhelming there are three crux issues the inquirer can examine: (1) the two natures of Christ controversy and Leo’s Tome (Chalcedonian versus Non-Chalcedonian), (2) the Filioque clause (Roman Catholicism versus Eastern Orthodoxy), and (3) sola fide and sola scriptura (Roman Catholicism versus Protestantism).

For most people I recommend they visit the Liturgy of the local Orthodox parish and ask: Is this the same way the early Christian worship? Is the faith taught at the Liturgy the Apostolic Faith?

Non-Historic Churches

Protestantism comprises churches that have no historic ties going back to the original Apostles. Protestantism’s historic roots only goes as far as 1500 because of their rejection of Rome’s magisterium and because of Rome’s excommunication of Luther and his followers. The fact that Protestants are denied access to Communion in the Roman Catholic Church is a visible sign of their broken ties with the original Apostles.

So if a new Christian convert were to look at the Yellow Pages listing of Protestant churches, he or she would have many decisions to make. Take baptism, should baptism be by total immersion or is sprinkling okay? If the former, then one should become a Baptist; if the latter, then one should become a Presbyterian or Methodist. And if one desires one’s children to be baptized then the Baptists are definitely out, and one should consider the Lutherans or Anglicans. If one believes in predestination then one should join a Reformed church but if one believes in free will then one should join either the Baptists or Methodists. Then if one wanted to become Lutheran, one has a choice of ELCA, Missouri Synod, and Wisconsin Synod. If one wants to become a Presbyterian, one has many more choices: PCUSA, PCA, OPC, RCA, CREC, ECO, Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America, etc. If one wants to be a Baptist, one has the choice of Southern Baptist, American Baptist, General Baptist, Freewill Baptist, or Landmark Baptist. Then, one also has to decide whether one should be a Pentecostal if one wants to experience the Holy Spirit or if one wishes to see signs and wonders. Or another issue is whether one is interested in social justice, if that is the case then one will wish to check out the more liberal mainline liberal churches. More recently, there have been differences over whether sexual morality should be redefined and whether hell is real. The problem here is choice, choices, and even more choices!

From my experience as an Orthodox Christian I can say there is substantial agreement with respect to theology, worship, and practice. Among the Eastern Orthodox churches the differences are mostly that of ethnic origins: Greek, Russian, Syrian, Bulgarian, etc. One will not find differences in worship style, like contemporary praise band versus ‘traditional’ hymns, or high church versus low church. If there are disagreements among Orthodox it is likely to be over pews versus no pews, or mixed language services versus all English services, or old calendar versus new calendar. These differences are minor compared to fundamental theological issues that split Protestant churches. This shows up most clearly in their worship. Many Protestants within the same denomination will not allow another pastor to substitute for the one they have now because they do not trust one another theologically. But Greek, ROCOR, OCA, and Antiochian Orthodox priests get a pass to substitute in leading the liturgy for each other in a routine way. Their differences are most administrative.

The Messiness of History

You asked: In light of the messiness of church history, how do I know which church is the true church? Among the historic churches you have three choices: Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, and Oriental Orthodoxy. You should study the issue the best you can, ask God for wisdom and discernment, and then make your commitment. Some might point out that I am advocating the use of private judgment and that “everyone knows” that private judgment is very prone to error. My response is that I am advocating personal judgment on the basis that even fallen human beings have the ability to think and to make choices, and that God desires that no one perish (2 Peter 3:9). The Orthodox doctrine of synergy recognizes our ability to respond to God’s gracious initiative even despite our fallen condition.

You complained: It doesn’t seem that Orthodoxy gives any clear stability when there is a crisis. I’m not sure what you mean by that. Do you wish that there was a five point formula by which an early Christian could check off to determine if a bishop or council went rogue? The controversies that wracked the early Church can be considered growing pains as the early Christians sought to understand the mysteries of the Incarnation and the Trinity. Out of these controversies the Latin and Byzantine churches emerged with a theological consensus informed by the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils. The tragedy of the Non-Chalcedonian churches may lie in the fact that these church bodies lay outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire. Similarly, the Schism of 1054 has roots in the growing cultural difference between the Latin West and the Byzantine East.

If you are wondering what advice I would give to a Christian caught up in such circumstances in the early Church, I would say: “Follow your bishop so long as he in communion with the Bishop of Rome and the other ancient patriarchates.” I would not say: “Read the Bible for yourself and make up your own mind on the matter.” The main thing is that the battles that led to the Ecumenical Councils are over and done with. We can visit the site of Gettysburg Battle and learn important lessons, but we don’t need to recreate the battle by shooting live bullets and bayoneting fellow Americans all over again!

My apologia for Eastern Orthodoxy is basically that the Holy Spirit guided the early Church, protected her against heresy, and that correct doctrine can be found in the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Second, the unity of the early Church was manifested in the Pentarchy comprised of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. I reject Oriental Orthodoxy because they do not formally accept all Seven Ecumenical Councils and that their rejection of Leo’s Tome and the Fourth Council resulted in schism with the Pentarchy. I reject Roman Catholicism because I came to the conclusion that the insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed was an unauthorized theological and liturgical innovation. And, when it came to the issue of the Filioque I had to choose between Rome and the other four historic patriarchates. Was Rome alone right and the other four wrong? And who changed? Rome or the other four patriarchates? My conclusion is that despite Rome’s long history of doctrinal conservatism, by the year 1054 the Bishop of Rome went his own way when he unilaterally inserted a doctrinal novelty the Filioque into the Nicene Creed and refused to heed the objections of his fellow patriarchs. This also set a pattern that haunts Rome to this day in yielding to the pressure of social and for political power.

History is messy but one has to make a choice. Central to my critiques of Protestant theology is that its principle of sola scriptura is fundamentally flawed. Sola Scriptura renders Protestantism theologically incoherent and ecclesially fractured. This is based on a historical and sociological analysis. I am willing to debate the issue but my question to those who disagree is: Then what do you see is the underlying cause of Protestantism’s fissiparous nature? Those who wish to remain Protestant should be able to give a good theologically sound apologia or else their position ends up becoming: I’m Protestant because I like being a Protestant, not because I have good reasons for being Protestant.

I often wonder if people confuse the statement “the Orthodox Church is the true Church” with “the Orthodox Church is a perfect Church.” It seems that the expectation is that if Orthodoxy is true then it will never have experienced schism, no breakaway groups, and no bishop or patriarch espousing heresy. Rather, the Orthodox Church is a battle scarred survivor that despite its great suffering and great conflicts has faithfully held fast to the Apostle Tradition for two thousand years.

You alleged that my faith is not so much in Tradition as in the Orthodox Church. You wrote: “Your faith, then, seems to be not in the Orthodox tradition being less messy, but in the Orthodox church itself.” My response to that is: My trust is in Jesus Christ who is faithful to his promises that (1) he would establish his Church which would withstand the gates of Hell (Matthew 16:18) and that (2) he would send the Holy Spirit to guide his Church into all truth (John 16:13).

Protestant Diagnostics

You wrote that the problem with Protestantism is that they deny having traditions and that this leads them to impose their traditions “very rigidly” on people. You also asserted that the good use of tradition calls for critical appropriation of tradition and against competing interpretations at the time.

The good use of interpretive tradition in literature includes an ability to critique that tradition when it butts up against the literature or other information we can gather from the time period.

Such an approach would lead to revisiting of ancient theological controversies settled by the early Church Councils, e.g., Arianism (the denial of Christ’s full divinity), Modalism (the denial of the Trinity), Montanism (ecstatic prophecy equally authoritative to Scripture), or Gnosticism (the denial of the bodily resurrection of Christ). Protestantism’s lack of a binding interpretive tradition has opened the door to these ancient heresies. Are you calling for an open hermeneutics that allow for these views?

I suspect that you may be arguing for an open hermeneutics that can provide balance to extreme positions like the young earth creationism reading of Genesis popular among Evangelicals. The problem here is that certain Evangelicals in their zeal to uphold the authority and inspiration of Scripture have elevated certain interpretation of Scripture to the level of dogma apart of the Church Catholic. Lacking the binding authority of the Ecumenical Councils and falling back on the opinions of certain individuals or denominational groups Protestant hermeneutics has become profoundly and tragically fragmented. The proper diagnosis here is not the absence of a flexible interpretive tradition. Rather, what is tragically missing is the absence of a universally binding interpretive Holy Apostolic Tradition that provides unity and constrains extreme interpretations of Scripture.

To return to the debate between the two Presbyterian groups in Fr. Andrew’s article “My Presbyterian Field Trip,” the PCUSA and ECO, how does your proposal for a flexible and self-critical interpretive tradition prove helpful? Is it not a fact that the PCUSA as a denomination has been quite open to new interpretations? Would you then agree with those calling for a Third Way that for all these years the Christian Church’s prohibition against homosexuality has been based on a misreading of Scripture? Would you also then assert that conservatives like ECO are too rigid in their interpretive tradition? Would you like Adam Hamilton call for a local option in which there is freedom to “agree to disagree”? Your possibilities, if you are Protestant, are legion and troubling.

Greek New Testament

You suggested that textual variation in Bible manuscripts are distortions that require corrections, and that the original Apostolic Tradition has in a similar fashion undergone distortion and thus require a similar kind of correction. You are exaggerating the situation here. Yes, there have been transmission errors but the text we have today is recognizably similar to the original text. For your analogy to hold there ought to have been a pattern of multiple textual traditions resulting in several different New Testaments with several different kerygmas (core messages). More apropos is the struggle in the early Church to define the New Testament canon, especially to exclude heretical books. Can you imagine if different churches had different canons and different creeds?! Fortunately, that was not the case. The early bishops did such a good job that the pseudepigrapha have become little known curiosities. Why? Because the Holy Spirit led the Church as Christ promised He would. Otherwise you would now have canonical chaos. The fact that the biblical canon is more or less a settled matter is something most Christians take for granted.

You closed with the statement that you don’t want to affirm anything that contradicts the Greek text of the New Testament. That is why it is important for someone in your position to check out Orthodoxy before committing to the Orthodox Church. I suggest you make a list of Orthodox teachings or New Testament passages that you find problematic, then write to me using the Contact form provided on the Home Page. Or you can forward these questions to an Orthodox priest knowledgeable in these matters or an Orthodox seminary professor.

Should you begin to seriously consider becoming Orthodox, the issue you will need to confront is the Orthodox Church’s stance that the Byzantine Text is the preferred text for teaching and instructing in the faith. Keep in mind that Orthodox scholars do use the Critical Text for their research so conversion to Orthodoxy might not be all that restrictive for someone in your position. If you have any further question on this matter, I suggest you write to an Orthodox seminary professor who engages in biblical studies.

Into the Fire?

Is Orthodoxy theologically coherent? In comparison to the diversity of beliefs and practices found in mainline Protestantism and popular Evangelicalism, the Orthodox Church is remarkably coherent. If one talks with an Orthodox priest one will find consistency with respect to their Christology, doctrine of the Trinity, the real presence in the Eucharist, the liturgical form of worship, the sinfulness of abortion and same sex marriage. And what Orthodox priests teach will be consistent with the teachings of the early Church Fathers. What inquirers need to keep in mind is that the divisions among the historic churches are quite few in comparison with Protestantism. Furthermore, the Eastern Orthodox and the Oriental Orthodox churches have demonstrated a doctrinal and liturgical stability remarkable in comparison to that found in Western Christianity, both Roman Catholic and Protestant. So to answer the question: Is converting from Protestantism to Orthodoxy like jumping out of the frying pan into the fire? My answer is: No. Orthodoxy has its problems but it has a stability of faith and worship that bears witness to its faithfulness to Apostolic Tradition.

Robert Arakaki

Resources

Paul M. Blowers. 1997. “The Regula Fidei and the Narrative Character of Early Christian Faith,” Pro Ecclesia 6, pp. 199-228.

Christopher S. Grenda. 2013. “Giving Up on the Founding: The Separation of Church and State and the Writing of Establishment Clause History” Politics and Religion (June), pp. 402-434.

Recent Comments