This article is a reposting of an article published on 29 May 2012.

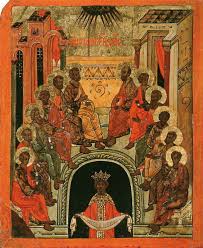

The Orthodox Church celebrates Pentecost as the fulfillment of Christ’s promise that the Father would send the Holy Spirit to His Church to lead Her into all Truth.

“But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you.” (John 14:26)

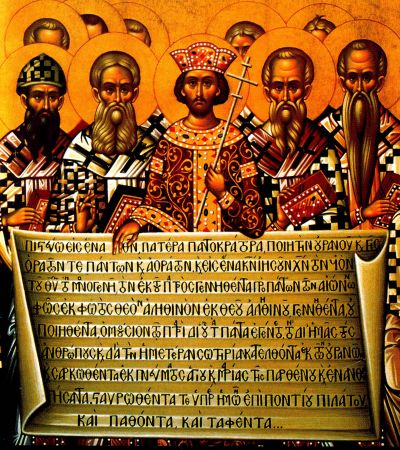

This abiding presence of the Holy Spirit in the Church is foundational to Orthodox Christianity. The Holy Spirit is God with us, who leads the Church through the Liturgy, gave supernatural courage to the early martyrs, and guided the Ecumenical Councils to defeat the various heresies. The Holy Spirit led the bishops in the formulation of the Nicene Creed and in defining the canon of Holy Scripture. Indeed when we look at church history we see the work of the Holy Spirit. The power of the Holy Spirit preserves the Faith once for all delivered to the Saints.

What sets Orthodoxy apart from the Protestant understanding of Pentecost is Orthodoxy’s strong corporate sense of the Holy Spirit. In the Bible the Holy Spirit is given to the Church corporately, through the Apostles to their disciples in the laying on of hands, to ensure the preservation of Tradition. This corporate and historic view of Pentecost and its implications offer a sharp contrast to Protestant views and practices in which the role of the Church is minimized or neglected.

In Protestantism the Holy Spirit is understood to be given to individual believers separately, privately and independently of the Church (which is assumed to be flawed and weak). In this blog I will be comparing the two traditions’ understanding of Pentecost.

The River of God Flowing into History

The River of God Flowing into History

The prophet Ezekiel had a vision of the eschatological temple. In chapter 47, he tells of a stream of water issuing from the altar in the New Temple. As this stream of water gets longer, it grows deeper and wider. It then branches out in various directions and wherever it goes it brings renewal and healing.

This prophetic vision was fulfilled on Pentecost. The Apostle Peter in his Pentecost sermon opens by quoting the prophet Joel: “And it shall come to pass in the last days, says God, that I will pour out of My Spirit on all flesh” (Acts 2:17; OSB; emphasis added). Pentecost also fulfills a prophecy made by Christ. In John’s Gospel Jesus announced:

If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water. But this He spoke concerning the Spirit, whom those believing in Him would receive; for the Holy Spirit was not yet given, because Jesus was not yet glorified. (John 37-40; OSB)

We enter into Ezekiel’s prophetic vision in our conversion to Christ. In the Septuagint version of Ezekiel 47:3 we read that the river was the “water of remission.” This is fulfilled in our baptism when we are baptized into Christ and receive forgiveness for our sins. The word “poured out” is also found in Romans 5:4 which talks about “the love of God being poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who was given to us.” (OSB; emphasis added.)

Ezekiel’s prophecy presents a vivid picture of trees lining the side of the great river:

Along the bank of the river on this side and that, will grow all kinds of trees used for food. Their leaves will not wither, and their fruit will not fail. They will bear fruit every month, because their water flows from the sanctuary. Their fruit will be for food, and their leaves for healing. (Ezekiel 47:12; OSB; emphasis added.)

This verse is a picture of a spirituality rooted in divine grace. It echoes Psalm 1 which describes a life grounded in the reading and meditation of God’s Law. This verse also echoes Genesis 2:10-14 which describes how the Garden of Eden had a river that flowed in four different directions. The trees bearing fruit year round in Ezekiel’s prophecy can be understood as the restoration of the access to the Tree of Life forfeited by Adam and Eve. The river lined with fruit bearing trees can be understood as the Church as the river of God. It can also be understood as the Church as a tree offering the healing life-giving fruits of the Cross (Christ’s body and blood that we receive for life everlasting). Ezekiel’s vision of the river of life is recapitulated in the book of Revelation 22:1-5 with a slight twist, a Christocentric reference is made to the Lamb of God slain for the salvation of the world.

Church History as the River of God

The book of Acts is fundamentally a theological book. Luke structured his narrative along the lines of a particular trajectory framed by the Great Commission (cf. Matthew 28:19-20, Luke 24:47-49). Acts 1:8 sketches the three phases of the book: Jerusalem (the Jews), Samaria (the half-Jews), and the Gentiles (the ends of the earth or the non-Jews). Acts begins with Jesus’ original followers in Jerusalem and the Gospel being preached primarily to the Jews (Acts 1-11). This is the Jerusalem phase. Then we see Gospel preached to the Samaritans (Acts 8). It is not until we come to Acts 13 that we read of the Church engaged in intentional missions when the Church at Antioch sends out Paul and Barnabas to evangelize. Acts closes with Paul reaching Rome, the political capital of the Roman Empire and preaching the Gospel freely for two years. What we see is the river of God flowing into history from Jerusalem into the various parts of the Roman Empire as foretold by Ezekiel.

Protestant Version of Church History — Disruption

What happened afterwards? Did the river of God that began on Pentecost in Acts 2 run dry? One would think so given the widespread belief among Protestants that a general apostasy occurred soon after the original Apostles passed on. Many believed that Christianity remained largely in spiritual darkness (with the exception of a “faithful secret remnant”) for the next thousand years or more until Martin Luther rediscovered the true Gospel. Another trope used by Protestants hold that the early church valiantly bore witness to the Gospel but was captured by Emperor Constantine and transformed into an institutionalized church barely recognizable to the original Christians. This historical trope is important for Protestant theology because it needs some kind of disjuncture (apostasy or compromise) to justify its claim that the Protestant Reformation was necessary for the restoration of Gospel and Church of the New Testament. If there was no such break then there would be no need for a Reformed Church separated from the Church of Rome.

Ralph Winter, a prominent Protestant missiologist, called this the BOBO theory — that the Christian faith Blinked Off after the apostles, then Blinked On in our time or whenever our church began (1517 for Protestants, 1823 for Mormons). But there is no hint whatsoever in Scripture that Blinked Off-Blinked On would happen to Christ’s Church especially in light of Christ’s promise that he would not leave them orphans but would send the Holy Spirit to guide them and protect them! Nor is there historical evidence that the Christian faith went AWOL for almost fifteen hundred years! The uncompromising witness of the martyrs in the face of persecution and the early church’s memorializing the martyrs contradict the notion of a widespread early apostasy. Ralph Winter’s article described how the Gospel advanced among the barbarian tribes even during the so-called Dark Ages.

While Rome and Western Europe saw the collapse of civilization and the onset of the Dark Ages, it must be kept in mind that in the Byzantine East culture, commerce, and learning continued to thrive for almost the next thousand years. Thus, the Protestant paradigm of church history has two major problems: (1) it cannot be supported by historical evidence and (2) it contradicts the promises given by Christ to his followers. Ultimately, the BOBO view of church history is a denial of Christ’s promise to send the Holy Spirit to be in and with the Church throughout history.

In their approach to church history many Protestants make two mistakes: (1) they assume that the church in the New Testament was Protestant in structure and practice, and (2) they ignore the historical continuity between Eastern Orthodoxy and the Church of the first millennium. The Protestant dismissal of the Orthodox understanding of church history with a wave of the hand is astounding. They assume this without looking at the evidence! But, the fact is that the pre and post Nicean Church simply did not look anything like a Protestant Church. Very early on Christians crossed themselves frequently. Early Christian worship was focused on the Eucharist, not the sermon, and all Christians held to the real presence in the Eucharist. Christian initiation was done via the sacrament of baptism after a lengthy process of instruction in which one had to commit to memory a creed. The early church was episcopal in structure (ruled by bishops) and conciliar (major decisions made by gatherings of bishops).

That the early Christians followed these practices is supported by leading scholars with no axe to grind. Highly recommended are: Jaroslav Pelikan’s magisterial The Christian Tradition, J.N.D. Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines,Oscar Cullmann’s Early Christian Worship, W.H.C. Frend’s The Rise of Christianity. For primary sources highly recommended are: The Apostolic Fathers, Irenaeus’ Against the Heretics, and Eusebius’ Church History.

This unfounded assumption resulted in Protestants misreading the New Testament and the early church fathers. There is in the Reformed tradition a growing appreciation of the fact that original Reformers like Calvin had a high regard for the church fathers. But even here, the Reformers’ appreciation of the church fathers was limited and selective. When the fathers’ writings seem to support Protestant ideas, Calvin and the Reformers freely quoted Athanasius and Augustine. But these same Fathers were ignored when they spoke on the rule of bishops, the Eucharist, church unity, the place of Holy Tradition, and a theosis union with God.

Orthodox Version of Church History – Continuity

The trope of church history as the river of God is useful for understanding Orthodoxy. The trope of the river of God assumes a fulfillment in history of Christ’s promises that the Holy Spirit would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13) and that it would be stronger than the powers of Hell (Matthew 16:18). The Orthodox Church believes that we can expect to see these Scriptural promises fulfilled throughout the age of the church. It believes that what began on Pentecost continues to the present day.

The Orthodox Church is the river of God flowing in the book of Acts into the two millennia continuously and without break to the present day. This trope assumes a fundamental continuity in terms of doctrine, liturgy, and spirituality from Pentecost to the present day. If Orthodoxy can support its claim to historical continuity then Protestants will need to reexamine their assumption of a fundamental break occurring in church history and with that the need for a Reformation.

Worship. The Eucharist has been integral to Christian worship from the beginning. The Orthodox Church uses the Liturgy of St. James which dates to the first century in Jerusalem, the Liturgy of St. Basil which dates to the fourth century and the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom which dates to the fifth century. Without exception, the Eucharist has been a part of the Sunday worship in Orthodoxy. The same cannot be said of Protestant worship. Most Protestant churches celebrate the Eucharist infrequently. While many Reformed, Anglican and Lutheran Christians claim to practice weekly communion, their claim rings hollow in light of the fact that they reject the historic understanding of the real presence in the Eucharist.

Leadership. Pastoral authority in Orthodoxy is grounded in apostolic succession. The five ancient patriarchates can all trace their spiritual lineage back to the original Apostles. Protestantism, due to its being a schismatic break off from the Papacy, cannot lay claim to apostolic succession. Apostolic succession is more than formal authorization but a sharing in the Holy Spirit across the generations that goes back to the original Pentecost in Acts. Critical to apostolic succession is faithfulness to the “pattern of sound words” (II Timothy 1:13). Thus, while Anglicanism can claim to possess apostolic succession, the fact that many of its current bishops hold blatantly heretical views undermines this claim. In short, in no way can Protestants claim continuity in leadership.

Doctrine. An important means of maintaining doctrinal unity in the early Church are the Ecumenical Councils. The entire Church of the first millennium accepted the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Protestantism has abandoned them in several ways: (1) it passively accepted the Papacy’s insertion of the Filioque clause and (2) it downgraded the binding authority of the Nicene Creed with its novel doctrine of sola scriptura. Having rejected the binding authority of the Seven Ecumenical Councils Protestant churches underwent a bewildering number of doctrinal permutations that would be unrecognizable and unacceptable to the early church fathers.

Spirituality. There is a rich stream of spirituality running through the history of the Orthodox Church. One of the best examples is the lives of the saints. The Orthodox Church considers them heroes of the faith whose lives exemplify the power of the Holy Spirit to transform lives throughout the history of the church. Orthodoxy can point to Saint Polycarp who boldly confessed Christ even when the Roman governor threatened to burn him alive, Saint Mary of Egypt a prostitute who spent decades in the desert in order to cleanse her soul, Saint Athanasius who defended the divine nature of Christ against the heresies of Arius, Saint Gregory Palamas who expounded on the uncreated light of Mount Tabor, the Chinese Martyrs of the Boxer Rebellion, Peter the Aleut martyred in San Francisco in the early 1800s, Father Arseny who suffered in the Soviet gulags. The river of God flows on!

When one looks for the heroes of the faith in Protestantism, especially in popular Evangelicalism, what one is likely to find are popular radio preachers, well respected seminary professors, and celebrity athletes. Many of these Protestant celebrities will be forgotten in time. It would be hard for a Protestant to claim a rich and unbroken history of spiritual formation.

When one compares Orthodox with Protestant spirituality, we find a marked sobriety and stillness in Orthodoxy not often found in Evangelical and Pentecostal circles where emotional fervor and free expression typically dominate. All too often the charismatic quest for a continuous spiritual high has led to burn outs and spiritual collapse. Christians in Reformed and mainstream Protestantism struggle with a spirituality grounded in cerebral propositional reasoning rather than that inner stillness nourished by the liturgical worship found in historic Orthodoxy.

Come and Drink!

On Pentecost Sunday Orthodoxy celebrates Pentecost in a special service that comprises three long kneeling prayers. Aside from this annual service, Pentecost is an ongoing reality in Orthodoxy. It is experienced in the sacramental and liturgical life of the Church. It is experienced vividly in the monastic communities.

In Protestantism the individual reception of the Holy Spirit overwhelms the understanding of the Holy Spirit being given to the Church. There has been much debate between Evangelicals and Pentecostals over whether the baptism in the Spirit occurs when one has a born again experience or as a separate event accompanied by speaking in tongues. What the two sides have in common is their silence on the role of the Church. However, historically one receives the Holy Spirit in the sacrament of chrismation which follows the sacrament of baptism. This sacramental approach to Christian conversion avoids Protestantism’s subjectivism. To those who deny the efficacy of sacraments I would respond that the sacraments are no mere rituals anymore than wedding vows are just words. For the Orthodox, Pentecost is not so much something I experience by myself, but through life in the Church. Life in the Church is like the River of God in which we are immersed into its water of life (the sacrament of baptism) and eat of the fruit of the tree (partake of the Eucharist). To the Protestants and Evangelicals who are spiritually thirsty, the Orthodox Church says: Come and Drink!

Recent Comments