Beauty so ancient and so new

Some of the readers of the OrthodoxBridge have questioned whether there is in fact a trend of Protestants converting to Orthodoxy. One important evidence can be found in “Searching for the Historic Christian Church: The Allure of Eastern Orthodoxy” by Pastor Mike Brown. The article opens with:

In the past five or six years, I have known several people who have left Reformed Christianity for Eastern Orthodoxy. Their reasons for making that decision varied. Some were mesmerized by the beauty of the Divine Liturgy. Others found Eastern Orthodoxy (hereafter EO) to offer a greater appreciation for mystery and religious experience than what they had known as a Protestant. All of them, however, were attracted by and eventually convinced of EO’s claim to be the original church founded by Christ. (Emphasis added.)

While small, the number of Reformed Christians becoming Orthodox has become a matter of pastoral concern. Among the converts are longtime seasoned elders and pastors well-read in Reformed theology. Dissatisfaction with the shallowness of contemporary worship and a hunger for a connection with the Ancient Church are compelling people to become Orthodox. Pastor Brown notes:

Many Protestants and evangelicals attest to feeling disconnected with the ancient church, and desire greater certainty that the church they attend has not been drastically changed by the world over the passing centuries.

Pastor Brown broke down the quest for the Ancient Church into three attractions: (1) continuity in worship, (2) continuity in doctrine, and (3) continuity in church government. In the first part, he gives an assessment of Orthodoxy’s claim to antiquity, then presents what the Reformed tradition has to offer. He is to be commended for his generally accurate presentation of Orthodoxy. In doing so, he avoids the fallacy of the straw man argument that often mars Reformed critiques of Orthodoxy. In the second part of his article, Pastor Brown seeks to show that “there are good reasons for Reformed Christians to be confident that they belong to the historic Christian church” and that there is thus no need for them to convert to Orthodoxy.

Part 1 – Pastor Brown’s Critique

Continuity in Liturgical Worship

Pastor Mike Brown challenges Orthodoxy’s claim to historical continuity in worship. He writes:

However, regarding EO’s claim to unbroken succession in its worship, I make two observations. First, the notion that the Divine Liturgy has been in place since the days of the apostles is misleading and grossly oversimplified. While it is true that certain components of the Divine Liturgy were present in the liturgies of the ancient church (i.e. Scripture reading, weekly communion, the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and creeds, etc.), there is no evidence that the basic form of the Divine Liturgy was used by the apostles or universally practiced by churches in the first few centuries. (Emphasis added.)

I found what Pastor Brown meant by “the basic form of the Divine Liturgy” in this critique to be vague. Is he referring to a regular pattern of worship or to something specific like the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom? It seems Pastor Brown understands Orthodoxy’s claim to continuity of worship to consist in its possessing a fixed, detailed order of worship from Day One. This can be seen in the phrase “looking identical” in the quote below.

Likewise, the most reliable documents from the post-apostolic early church, such as the Didache (c. 2nd century) and Justin Martyr’s First Apology (c.155-157), provide us with evidence that worship in the ancient church consisted of Scripture reading, preaching, singing, the Lord’s Prayer, and weekly communion. These, however, show no signs of looking identical to the Divine Liturgy of the Orthodox Church. In fact, the oldest surviving liturgy in use by EO today is the “Liturgy of St. James,” which dates no earlier than the 4th century. EO’s claim that its liturgy has remained unchanged since the days of the apostles is unsubstantiated and overstated. (Emphasis added.)

Orthodoxy has never made the claim for a fixed Liturgy from Day One. Nor has it claimed that the Divine Liturgy looked identical to the worship of the New Testament Church. Anyone reading early church history will soon realize that this was not the case. During the first three centuries, a general shape of the liturgy prevailed across the world, even in the midst of diverse practices. In time Christian worship became uniform and fixed in order and form. Indeed, Pastor Brown’s use of “looking identical” indicates he does NOT understand, or intentionally hyperbolizes Orthodox continuity!

The flaw in Pastor Brown’s critique is his focus on external form without taking into account the inner meaning of Christian worship. The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese’s website article “Introduction to the Divine Liturgy” which he quoted from took care to stress the continuity in inner meaning:

But whatever were the various forms of the Divine Liturgy of the primitive Church, as well as of the Church of the final formation of the Divine Liturgy, the meaning given to it by both the celebrants and the communicants was one and the same; that is, the belief of the awesome change of the sacred Species of the Bread and Wine into the precious Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, the Lord. (Emphasis added.)

Pastor Brown comes close to constructing a straw man argument especially in light of the fact the article takes care to note that underneath the variation in outward form in Christian worship has been the constant belief in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist.

Form versus Inner Meaning

Central to Christian worship from the start was: (1) the celebration of Christ’s death and resurrection in the Eucharist, and (2) the belief in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. An examination of early Christian worship and the writings of the early Church Fathers show the universality of these two defining elements. These two elements define Orthodox worship even today. It would be unthinkable for an Orthodox parish to have a Sunday service that consists only of the Liturgy of the Word or for the priest to declare that Eucharist was just symbolic. What is not central to Orthodox worship is a long sermon in which the pastor shows off his rhetorical skill and unique exegetical insights week after week. Indeed, in the Liturgy the Orthodox priest essentially disappears behind the form of the Liturgy and attention is focused on the worship of the Trinity.

When we compare Reformed worship with early Christian worship two facts become apparent: (1) a new form of Sunday worship has emerged that is sermon-focused and (2) the rejection of the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. In his attempt to show how Reformed worship conforms to early Christian worship Pastor Brown brings to the reader’s attention Calvin’s Genevan Psalter of 1542, which was “according to the custom of the ancient church.” However, invoking historical documents like the 1542 Genevan Psalter or Calvin’s Institutes 4.17.44 does not negate the fact that a new pattern of worship has come to dominate the Reformed tradition. Two questions quickly reveal the flaw in Pastor Brown’s claim:

- Is it the norm for Reformed churches to celebrate the Lord’s Supper every Sunday?

- Is it the norm for Reformed churches to teach and affirm that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ in the Lord’s Supper?

In most instances, the answer will be “no.” It is interesting to note that in Note 25, Pastor Brown cites Michael Horton’s article “At Least Weekly” and Keith Mathison’s book Given For You: Reclaiming Calvin’s Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper to show that an attempt is being made in Reformed circles to recover historic Christian worship. What he does not realize is that this very attempt at recovery is an admission that something has been lost. It is no wonder that many Reformed Christians are feeling the loss and are looking to Orthodoxy to regain it.

The Orthodox conversions Pastor Brown is trying to halt are happening even in the most liturgical and sacramental churches in the Reformed community. Indeed, something historic has been lost, otherwise there would be little interest among Reformed folks in learning about the Liturgy and Eucharistic practices in the Early Church. This loss is compelling many to find their roots in the Orthodox Church. Retreating back only as far as Calvin and the 1500s, has not satisfied many.

Probably the greatest disconnect has been with respect to the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. The vast majority of Protestants and Evangelicals today believe that the Holy Communion (Eucharist) is just a symbol. This marks a major break from historic Christian worship. Ignatius of Antioch noted that it was the heretics who denied that the Eucharist “is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ” (Letter to Smyrnaeans 7.1). Interestingly, John Calvin in no uncertain terms denounced the teaching that the Eucharist is symbolic as an “error not to be tolerated” (“Confession of Faith Concerning the Eucharist” in Reid p. 169). Is it not striking that nowhere in his article does Pastor Brown discuss the consecration of the bread and wine or the real presence in the Eucharist? Could it be that these are unimportant issues for him? Or perhaps too dangerous to broach?

Pastor Brown seems to think that, by following certain historic practices, Reformed churches are “preserving a connection to the worship of the ancient Christian church.”

By retaining ordinary practices such as the Lord’s Prayer, Psalmody, and weekly communion, we can be confident that we are worshiping God in the same way as the ancient church, and have not merely followed a new tradition.

All of these elements are, of course, important to historic Christian worship but are they enough? The desire for a retrun to historic worship, in reaction to the excesses of contemporary worship, is only part of the reason that people are drawn to Orthodox worship. Many are drawn to a worship that goes beyond intellectual stimulation to real communion with God. Perhaps they are drawn to the mystical reality behind the liturgical forms but overlooked by Pastor Brown? Many inquirers are tantalized by the promise given by Christ himself:

For my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I in him. (John 6:55-56)

Orthodoxy believes that, in the Eucharist, the bread and the wine become the body and blood of Christ and that when we go up for Holy Communion we actually partake of the body and blood of Christ.

Right Doctrine

Many Reformed Christians are drawn to Orthodoxy out of a need for assurance that what they believe is not man-made doctrine, but the historic Christian Faith. Pasto Mike Brown writes:

A second area where many Christians complain of feeling an historic void in their faith is doctrine. Just as they want to be confident that they are worshiping God the same way the apostles and early church did, they also want to be sure that the teachings and beliefs of the church they attend conform to that history as well.

Pastor Brown responds to this hunger for historic doctrine by criticizing Orthodoxy for its “superficial” theology. He notes:

Thus, it is difficult not to find EO’s claim to uninterrupted continuity in its doctrine to be superficial as they possess no unifying confession on matters of essential Christian doctrine beyond the seven Ecumenical Councils. It is unsatisfactory and unfair to ignore debates on important biblical teaching simply because those debates arose in the west after the 8th century. (Emphasis added.)

My response: “Why is it so important that a religious tradition have a detailed theological confession? What does it have to do with historical continuity?” Pastor Brown’s concern with detailed theological systems is historically conditioned, reflecting Protestantism’s intellectual roots in Medieval Scholasticism, e.g., Thomas Aquinas. Where Western theology seeks to understand God with the intellect, Orthodox theology starts from the understanding that genuine knowledge of God comes through prayer and worship.

Pastor Brown’s complaint about Orthodoxy’s theology being “superficial” is perplexing. Many of the original Protestant confessions have become historical curiosities that many, including pastors and elders, tend to honor only in name. In recent years, many of these detailed statements of faith have been replaced by broadly-phrased confessions of lowest common denominator. It is ironic in the face of the Reformed tradition’s plethora of confessions that Pastor Brown would complain that Orthodoxy has “no unifying confession.” There is no unifying confession for the Reformed tradition either! Where the Lutherans have the Book of Concord, there is no similar unifying confession for the Reformed tradition. While the Westminster Confession is probably the most widely known, it is not the doctrinal standard for the entirety of the Reformed tradition.

How effective are detailed confessions for preserving doctrinal orthodoxy? Pastor Brown is probably too embarrassed to make mention of the fact that his denomination, the United Reformed Churches in North America (URCNA), was the result of a schism in the 1990s when a sizable group felt the Christian Reformed Church in North America was moving away from the truths of the Reformation. Apparently, the split resulted from tensions between theological conservatives and liberals. Those who are interested in the details of the split might be interested in reading Robert P. Swierenga’s Burn the Wooden Shoes: Modernity and Division in the Christian Reformed Church in North America (2000). Is it not telling that the so-called Three Forms of Unity (the Belgic Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, and the Synod of Dort) have been unable to guarantee doctrinal stability in the face of theological liberalism for the past two centuries? The lesson here is clear – even detailed, precisely-worded confessions are not strong enough to withstand the onslaught of modernity.

While Orthodoxy may not have a precise theological system like Protestantism, there is within Orthodoxy a hidden strength that most Protestants do not see – liturgical theology. In the Divine Liturgy doctrine is fused with worship. If one listens to the hymns and prayers, he will hear every Sunday the core dogmas of the Christian Faith: the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Good News of Christ’s saving death and resurrection. Although alien to Protestantism, liturgical theology is an ancient way of doing theology. Irenaeus of Lyons wrote: “But our opinion is in accordance with the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn establishes our opinion” (Against Heresies 4.18.5). Basil the Great in his On the Holy Spirit defends the divinity of the Holy Spirit from the trinitarian prayers used in the Liturgy. The ancient saying “Lex orandi, lex credendi” (the rule of prayer is the rule of belief) describes how our worship informs our doctrine.

Continuity in Church Governance

Another reason why many Reformed Christians find Orthodoxy appealing is its claim to apostolic succession. God is the God of history. He created mankind then acted through men within human history. The historical books and the detailed genealogies in the Bible point to the importance of our roots in history. Just as genealogies were part of the Mosaic covenant community, Israel, so likewise is apostolic succession the genealogy of the new covenant community, the Church. It is proof that there exists a historic, unbroken continuity that links the present-day episcopacy back to the original Apostles. Without history, Christianity would be a philosophical system of abstract ideas, rather than a concrete way of life and a community of people.

In his critique, Pastor Brown draws on Michael Horton’s argument that the Galatian churches’ succumbing to the Judaizing heresy was enough to refute Orthodoxy’s claim that doctrinal orthodoxy is preserved by means of apostolic succession. However, the episcopacy does not stand alone, but in the context of the Church Catholic. The notion of an independent bishop is self-contradictory. If one bishop falls into error, his fellow bishops will be there to correct him. Is it not curious that Pastor Brown failed to mention the role of the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 in resolving the crisis that erupted in Galatia? The Jerusalem Council provided the precedent for the Ecumenical Councils. In the Councils, apostolic succession in its collective expression functioned to preserve right doctrine.

As a Reformed theologian, Michael Horton is hostile to the episcopacy. For him, apostolic succession takes place through the gospel. Reading Horton’s assertion that what counts is preaching the same gospel that the Apostles proclaimed one can’t help but wonder if by “gospel” he means the doctrine of sola fide which was supposedly “recovered” by Martin Luther in 1517. The Good News of Jesus’ death and resurrection has always been part of the historic Christian Faith, but the categories of imputed righteousness versus infused righteousness so crucial to sola fide are nowhere to be found among the early Church Fathers. It was not until after Anselm of Canterbury’s Cur Deus Homo set forth the satisfaction theory that the theological foundations for Luther’s sola fide was possible. If none of the early bishops taught sola fide, this makes sola fide suspect historically. It is a theological innovation alien to historic Christianity. It is no wonder then that Pastor Brown and Michael Horton are critical of Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic succession. Disavowing the historic episcopacy gives them the liberty to read the Bible according to their Protestant convictions.

For a discussion of: (1) the meaning of imputed and infused righteousness see the Theopedia article “Imputed Righteousness,” (2) the novelty of imputed and infused righteousness see my article “Response to Michael Horton,” and (3) the novelty of sola fide see my article “Response to Theodore – Semi-Pelagianism, Sola Fide and Theosis.”

Part 2 – Pastor Brown’s Apologia for Reformed Christianity

Church Fathers

Many Christians are naturally drawn to Orthodoxy because of its historic roots in the early Church. Pastor Brown responded to this by noting that the Protestant Reformers, most notably John Calvin, drew heavily on the early Church Fathers. However, to selectively quote the early Church Fathers does not in any way prove that one shares in the same faith as the early Church Fathers. None of the Church Fathers taught sola scriptura or sola fide – the two key teachings of the Protestant Reformation. Calvin and other Reformers engaged in cherry picking the Church Fathers to legitimize their novel Protestant doctrines. While they did quote from the Church Fathers, they did not subject their theology to the patristic consensus. This was because, under sola scriptura, the Reformers’ own readings of the Bible had greater authority than the Church Fathers’. Calvin praised the early Church Fathers when they supported his views and scorned them when they differed from his views. This implied that Calvin knew better than the Church Fathers! (Rock and Sand pp. 131-132.)

Pastor Michael Brown concedes that he and his fellow Reformed ministers could do a better job of “showing Reformed theology’s continuity with ancient and medieval theology.” My response is: “They could do a better job of reading the early Church Fathers with an open mind.” When I was studying church history at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, I read the early Church Fathers in order to improve my Protestant theology. Early on, I found the Church Fathers perplexing. This confusion was cleared up when I came to the realization that the early Church Fathers were not Protestant and that Protestantism was altogether different from the early Church. Facing up to this discontinuity was disturbing and disheartening, but brought clarity to my reading of the early Church Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils. The Protestant Reformation of the 1500s emerged from a different cultural and theological context. The Reformers’ theology was influenced by the medieval papacy, medieval canon law, an excessive reliance on Augustine of Hippo, the Via Antiqua of medieval Scholasticism, and far more than normally acknowledged, the Via Moderna of Renaissance humanism. Pastor Brown and others like him are mistaken if they think that selectively quoting the Church Fathers will take them back to the Faith of the early Church.

Icons

With respect to icons, Pastor Mike Brown stresses the Reformed tradition’s iconoclasm and argues that icons constitute a break from the historic continuity of Christian worship. He presents two lines of arguments: (1) patristic and (2) biblical.

For the “ample evidence” that icons were not tolerated in the early church, Pastor Brown gives three sources: (1) Irenaeus of Lyons, (2) Epiphanius of Salamis, and (3) the Synod of Elvira. The first thing to note is that Pastor Brown is being very selective with the evidence he presents to the reader. He makes no mention of any pro-icon sources. For the sake of fairness, he should at least have mentioned theological classics like John of Damascus’ Three Treatises on the Divine Images and Theodore the Studite’s On the Holy Images. Even more striking is his failure to mention the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787). Failure to mention these important evidences leaves the Reformed inquirer in “blissful ignorance.”

I was surprised that Pastor Brown cited Irenaeus of Lyons, one of the greatest Church Fathers, as being against icons. However when I read the passage cited (AH 1.26.6), I was disappointed to find that he had misread Irenaeus. Furthermore, the correct citation is 1.25.6, not 1.26.6. As a service to the reader I present the passage mentioned by Pastor Brown.

Others of them employ outward marks, branding their disciples inside the lobe of the right ear. From among these also arose Marcellina, who came to Rome under [the episcopate of] Anicetus, and, holding these doctrines, she led multitudes astray. They style themselves Gnostics. They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them. They crown these images, and set them up along with the images of the philosophers of the world that is to say, with the images of Pythagoras, and Plato, and Aristotle, and the rest. They have also other modes of honouring these images, after the same manner of the Gentiles. (Emphasis added.)

A careful reading of Against Heresies 1.25.6 makes it very clear that Irenaeus is describing and criticizing the practices of the Gnostics, a heretical group. It is astonishing that Pastor Brown paid no attention to the sentence: “They style themselves Gnostics.” I suspect that this blooper is largely due his unfamiliarity with the early Church and that in his haste he unwittingly projected Reformed iconoclasm onto Irenaeus of Lyons.

Reformed apologists like to cite the story of Epiphanius entering a church and ripping down a curtain with an image embroidered. Epiphanius was no obscure figure but a recognized saint. For Reformed apologists this is major evidence in support of iconoclasm. This argument is not new. As a matter of fact it is the exact same argument made by the iconoclasts in the early Church. Theodore the Studite and John of Damascus knew of it and responded by noting that if one were to visit Epiphanius’ church one could see it decorated with images and Gospel stories. Furthermore, both Church Fathers asserted that the anecdote was a spurious forgery. Theodore the Studite in his On the Holy Icons wrote this hypothetical debate over icons:

Heretic: Epiphanius is one of them, the man who is prominent and renowned among the saints.

Orthodox: We know that Epiphanius is a saint and a great wonder-worker. Sabinus, his disciple and a member of his household, erected a church in his honor after his death, and had it decorated with pictures of all the Gospel stories. He would not have done this if he had not been following the doctrine of his own teacher. Leontius also, the interpreter of the divine Epiphanius’ writings, who was himself bishop of the church in Neapolis in Cyprus, teaches very clearly in his discourse on Epiphanius how steadfast he was in regard to the holy icons, and reports nothing derogatory concerning him. So the composition against the icons is spurious and not at all the work of the divine Epiphanius. (“Second Refutation” §49; p. 74)

A modern assessment of Epiphanius’ alleged iconoclasm can be found in Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Christian Tradition Vol. 2, page 102. It is important that Protestants inquirers know that even evidence like this presented by Reformed apologists their arguments are by no means slam dunks. There is another side of the story. To give the inquirers only one side of the argument is not fair to them.

But, what if the anecdote about Epiphanius is valid? What if one saint turned out to be an iconoclast? This is where the patristic consensus comes in. John of Damascus notes:

Nor can a single opinion overturn the unanimous tradition of the whole Church, which has spread to the ends of the earth. (On the Divine Images “First Apology §25; p. 32)

According to the patristic consensus, no single person’s opinion can represent the Christian Faith. This view must be expressed by the Church Catholic. Using poetic language, Theodore points out that a single swallow’s song does not mean that spring has come. It is worth noting that iconoclasm is not even a Protestant position, but peculiar to one strand of Protestantism, the Reformed tradition.

Reformed apologists like to cite the Council of Elvira as evidence against icons. The inquirer should be aware of three issues. First, Pastor Brown needs to show why we should give a minor local synod preference over an Ecumenical Council (Nicea II). An Ecumenical Council represents the ruling of the Church Catholic on a disputed issue. One cannot cherry-pick the councils on the basis of what one likes or does not like. Second, to endorse a council implies that one is willing to follow the rulings issued by that council. Pastor Brown accepts Canon 36 which seems to prohibit images, but then he ignores Canon 26 which imposes the Saturday fasts. Third, it is not clear from the original Latin whether Canon 36 stemmed from opposition to icons in general or whether it was out of concern that images painted on church walls would be vulnerable to vandalism (keep in mind that this synod was held during the height of the ferocious Diocletian persecution). The Synod of Elvira’s alleged iconoclasm stems from a faulty translation of the original Latin. Steven Bigham, an Orthodox priest, translated Canon 36 as follows:

It has seemed good that images should not be in churches so that what is venerated and worshiped not be painted on the walls. (in Bigham p. 161; emphasis added)

To sum up, the evidence that Pastor Brown presents for iconoclasm in the early Church is scanty and weak. He misread Irenaeus of Lyons. His anecdote about Epiphanius of Salamis was deemed a forgery by two notable Church Fathers. There is evidence that Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira cited by Reformed apologists is based on a flawed translation of the original Latin. In all fairness to Protestant inquirers, Pastor Brown should have alerted them to the issues relating to his evidences and the arguments in defense of icons in the early Church. Keeping Protestant inquirers in ignorance is not doing them a favor.

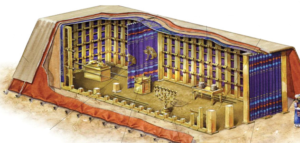

For his biblical critique of the Orthodox veneration of icons, Pastor Brown invoked the Second Commandment. However, one cannot just invoke the Second Commandment. There are important exegetical issues that need to be addressed. First, it is important to read the Second Commandment in its context. The First Commandment’s monotheism suggests that the Second Commandment was directed against the worship of the pagan deities of Egypt and Canaan, not against the use of images in Israelite worship. Second, in the latter half of Exodus one finds God instructing Moses to incorporate images into the Tabernacle (Exodus 26:1, 31). The entirety of the Mosaic Tabernacle, including the images, was intended to promote the true worship of Yahweh. The use of images was continued in Solomon’s Temple (2 Chronicles 3:7, 14). This suggests that there is indeed a biblical basis for the use of images in places of worship. Interested readers can read my article “The Biblical Basis for Icons.”

Little is known about Christian worship prior to the fourth century. Reformed Christians infer from this silence that the early Church was devoid of icons. However, if we take into account the striking images found in the Jewish synagogue and Christian church in Dura Europos that date back to the mid 200s one is confronted with positive evidence for the use of images in early Christianity. The archaeological evidences found in Dura Europos together with the biblical and patristic evidences taken together present a powerful witness in support of the use of icons in early Christianity. This is something that Reformed apologists have yet to address.

Differences in Personal Perspectives

I suspect that Pastor Brown’s enthusiasm for the Reformed tradition stems from his having been part of Calvary Chapel. In comparison to Calvary Chapel, which traces its origins to the Jesus Movement of the 1960s in California, the Reformed tradition is much more historic, going back to the Reformation of the early 1500s. Its teachings are definitely deeper in comparison and its worship more liturgical than Calvary Chapel’s informal approach. His glowing assessment of the Reformed tradition is further colored by his being part of the UCRCNA. As a new denomination that emerged in the 1990s, the UCRCNA is still a young and vigorous denomination. Sociologically, because schism functions as a method of self-selection that excludes rival views, it is not surprising that Pastor Brown has enjoyed oneness of mind among his fellow pastors and parishioners.

My personal perspective is different from Pastor Brown’s. Unlike Pastor Brown’s Reformed denomination which resulted from a schism, Congregationalism in Hawaii has a history of continuity going back to the Puritans. My being an Evangelical in the liberal UCC gave me a quite unique perspective on the Reformed tradition. This perspective was further refined when I was at Gordon-Conwell in Massachusetts, the heartland of New England Puritanism, and interacted with UCC liberals during that time. As a result of these experiences, I was able to appreciate the historic legacy of John Calvin and the New England Puritans while seeing up front the realities of liberal mainline Reformed Christianity. Unlike Pastor Brown’s unreserved enthusiasm for the Reformed tradition, my assessment was a mixture of respect, dismay, and consternation. My time in a liberal Reformed denomination caused me to question the long-term viability of the Reformed tradition, which made me open to Orthodoxy and the Ancient Church.

The Challenge for Reformed Apologetics

It seems that Pastor Mike Brown is unaware of how much the ground has shifted in the Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. In recent years, new Orthodox pro-icon apologia have emerged that refute the Second Commandment argument on exegetical grounds, draw on recent archaeological findings, and critically analyze the theological basis of John Calvin’s iconoclasm. These arguments are being raised by former Protestants who are familiar with Reformed iconoclasm and who, after prolonged study of the Bible and the Church Fathers, have come to embrace the pro-icon position of Orthodoxy. Interested readers can read my earlier articles, where I have discussed in greater detail the anti-icon arguments raised by Reformed Christians. I also recommend Gabe Martini’s detailed response to Pastor Steven Wedgeworth’s iconoclasm. Questions about the formal principle (sola scriptura) and material principle (sola fide) of Protestant theology have emerged causing a number of Protestant pastors and theologians to convert to either Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy.

Reformed apologists cannot simply repeat what worked in the past and ignore the newer arguments and issues raised by Orthodox apologists. They need to show that they are aware of these new arguments and are willing to engage them. Sadly, it does not appear that Pastor Brown shows a familiarity and mastery of this new material.

The Apostolic Failure of the Reformed Church

Pastor Mike Brown’s argument can be summed up: “We have the same things the Orthodox Church has. They have liturgies; so do we. They cite the Church Fathers; so do we. They have creeds; so do we. You don’t have to become Orthodox to be part of the Ancient Church. Reformed Christianity is Ancient Christianity!”

My response to all this is: “Come and see!” Visit an Orthodox Sunday Service. Experience the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom which dates back to the fifth century. Talk to the local Orthodox priest. Ask him what the Orthodox Church teaches about Christ, the Trinity, and prayer. Compare the Orthodox Church of today with the early Church. Follow the guidance of the Prophet Jeremiah:

Stand at the crossroads and look;

Ask for the ancient paths,

Ask where the good way is and walk in it,

And you will find rest for your souls.

(Jeremiah 6:16, NIV; Emphasis added.)

Robert Arakaki

Recommended Reading

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “A Response to John B. Carpenter’s “Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church.” OrthodoxBridge.com (16 September)

Robert Arakaki. 2012. “Response to Michael Horton.” OrthodoxBridge.com (10 May)

Robert Arakaki. 2011. “The Biblical Basis for Icons.” OrthodoxBridge.come (12 June)

Robert Arakaki. 2011. “Calvin Versus the Icon: Was John Calvin Wrong?” OrthodoxBridge.com (19 June)

Steven Bigham. 2004. Early Christian Attitudes toward Images.

Pastor Mike Brown. 2016. “Searching for the Historic Christian Church: The Allure of Eastern Orthodoxy” in www.ChristURC.org. (9 December)

“Synod of Elvira” Wikipedia.

Gabe Martini. “Is There a Patristic Critique of Icons?” (Part 3 of 5) (Council of Elvira) 20 May 2013.

Gabe Martini. “Is There a Patristic Critique of Icons?” (Part 4 of 5) (Epiphanius of Salamis) 22 Ma 2013.

Gabe Martini. “An Orthodox Response to John Calvin on Icons: Icons and Idolatry.” Pravoslavie. 6 December 2014.

Rev. George Mastrontonis. N.d. “Introduction to the Divine Liturgy” in Goarch.com

Jaroslav Pelikan. 2011. Imago Dei: The Byzantine Apologia for Icons.

J.K.S. Reid, ed. 1964. “Confession of Faith Concerning the Eucharist” in Calvin: Theological Treatises p. 169.

Carly Silver. 2010. “Dura-Europos: Crossroad of Cultures.” Archaeology Magazine (11 August)

Josiah Trenham. 2015. Rock and Sand: An Orthodox Appraisal of the Protestant Reformers and Their Teachings.

Recent Comments