This is a relaunch article. It marks the end of my blog vacation and the OrthodoxBridge moving to Ancient Faith Blogs.

Luther posting the 95 Theses

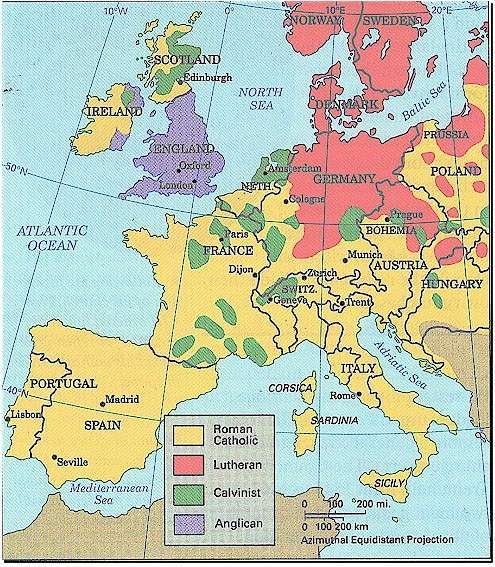

This Saturday will mark the 498th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. On 31 October 1517, Martin Luther nailed the 95 Theses to the door of Castle Church (Wittenberg, Germany) sparking a huge theological debate that would radically alter the religious landscape of Europe.Within a few decades the once unified European society was divided among competing Christian churches.

As we draw near to the 500th anniversary of Protestantism it would be good for Christians – Protestants and non-Protestants — to reflect on its origins and its legacy. And to ask the question: Was the Reformation Necessary? To answer this question, we need to first understand what justification was given for the Reformation. One of the finest apologia was written by John Calvin.

Historical Context

In 1543, Calvin wrote “The Necessity of Reforming the Church” in anticipation of Emperor Charles V’s convening the Diet of Spires (Speyer). Altogether there were four Diets (parliamentary assemblies) held at the town of Speyer situated on the river Rhine in Bavaria. During that period the Reformation was seen as a minor faction outlawed at the Diet of Worms (1521) and politically a nuisance. It is likely that the Reformation would have been quashed then and there if it were not for the fragile state of Europe’s political unity. The four Diets at Speyer trace the growth of the Reformation from a dissenting view into a separate church body independent of Rome.

At the first Diet of Speyer in 1526 in a moment of political and military weakness, Charles V was forced to accept the principle allowing each local ruler to rule as he wished: “every State shall so live, rule, and believe as it may hope and trust to answer before God and his imperial Majesty.” This decision in effect suspended the Diet of Worms and allowed the Lutherans to coexist with the Roman Catholics. (In 1526 the Turks were advancing in Hungary and later that year would lay siege to Vienna necessitating vigorous military action by the Emperor.) In 1529, Charles V was strong enough to seek the reversal of the 1526 resolution. While most complied, six rulers along with fourteen free cities objected. They drew up an appeal which would be known as the “Protest at Speyer”; the signatories would become known as “Protestants.” A third diet of Speyer was convened in 1542 for the purpose for rallying support against the Turks. The Protestant princes withheld support until the Emperor agreed to the Peace of Nuremberg (1532). A fourth Diet at Speyer was convened in 1544. This time Charles V needed support against two fronts, against Francis I of France and against the Turks. It was in this the context that Calvin composed “The Necessity of Reforming the Church.” By 1555 the Emperor would be forced to give legal recognition to the Lutherans in the Peace of Augsburg.

Historically, Calvin’s “Necessity of Reforming the Church” was not a game changer. However, Theodore Beza (1519-1605) considered this essay one of the “most powerful” of the time (Beza, p. 12). This review seeks to be sensitive to the fact that Calvin’s essay was written in the context of a Protestant versus Roman Catholic debate while assessing Calvin’s apologia for the Reformation from the standpoint of the Orthodox Faith. References and page numbers are from J.K.S. Reid’s Calvin: Theological Treatises (1954).

Iconoclasm and True Worship

Calvin’s first justification is the use of images in churches which for him impedes “spiritual worship.”

When God is worshipped in images, when fictious worship is instituted in his name, when supplication is made to the images of saints, and divine honours paid to dead men’s bones, and other similar things, we call them abominations as they are. For this cause, those who hate our doctrine inveigh against us, and represent us as heretics who dare to abolish the worship of God as approved of old by the Church (p. 188).

The critique was directed against Roman Catholicism which at the time was heavily influenced by the Renaissance. While there may have been excesses in the churches of Calvin’s time, his remedy was drastic – the removal of all images from churches. This is something no Orthodox Christian could endorse especially in light of the fact that iconoclasm was condemned by an Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787).

Strasbourg Cathedral – France Source

Calvin’s argument here is highly polemical with very little theological reasoning involved. Calvin’s failure to rebut John of Damascus’ classic defense of icons based on the Incarnation and the biblical basis for the use of image in Old Testament worship present a gaping hole in his argument for the necessity of the Reformation. See my critique of Calvin’s iconoclasm in “Calvin Versus the Icon.”

Spiritual Worship versus Liturgical Worship

Calvin’s next target is what he deemed “external worship” and “ceremonies” (p. 191). Calvin argues that there was a time when liturgical worship was useful (i.e., during the Old Testament) but that with the coming of Christ liturgical worship has been abrogated.

When Christ was absent and not yet manifested, ceremonies by shadowing him forth nourished the hope of his advent in the breasts of believers; but now they only obscure his present and conspicuous glory. We see what God himself has done. For those ceremonies which he had commanded for a time has now abrogated forever (p. 192; emphasis added).

This argument is a form of dispensationalism. While there are differences between Jewish and Christian worship, Calvin pushes it to the breaking point. Calvin’s dismissal of liturgical worship overlooks the fact that early Christian worship was liturgical. Evidence for this can be found in Volume VII of the Ante-Nicene Fathers Series p. 529 ff.

Calvin objects to external ceremonial worship on the grounds that it leads to the failure of people to give their hearts and minds to God (p. 193).

For while it is incumbent on true worshippers to give heart and mind, men always want to invent a mode of serving God quite different from this, their object being to perform for him certain bodily observances, and keep the mind to themselves. Moreover, they imagine that when they thrust external pomps upon him, they have by this artifice evaded the necessity of giving themselves (p. 193).

For Calvin true Christian worship consists of the preaching of Scripture and the inculcation of right understanding of the Gospel.

For the Orthodox Calvin’s derisive assessment of the Liturgy is hard to swallow. The Liturgy lies at the core of Orthodox life. On most Sundays we use the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom which dates to the fifth century and on 10 Sundays we use the older Liturgy of St. Basil which dates to the fourth century. Calvin’s argument here rests on the assumption that early Christian worship was basically Protestant in form (Reformed). This is highly questionable in light of the church fathers and historical evidence. Most likely the theological motive for Calvin’s anti-liturgical stance is his spiritual versus physical dichotomy.

In short, as God requires us to worship him in a spiritual manner, so we with all zeal urge men to all the spiritual sacrifices which he commends (p. 187).

Protestantism’s emphasis on the sermon and its downplaying of the embodied aspects of worship: bowing, prostrations, processions, candles, incense, etc. can be seen as originating from this dichotomy. There is no evidence that the early Christian worship was informed by this mind/body dichotomy. Where Calvin takes an either/or approach, Orthodoxy takes a both/and approach holding that the symbolism and ritual actions that comprise the Liturgy help us better understand Scripture.

Reforming Prayer

Calvin strongly objects to the intercession of the saints and to the practice of praying in an unknown tongue (pp. 194-197). He notes that there was a Catholic Archbishop who threatened to throw in prison anyone who dared to pray the Lord’s Prayer in a language other than Latin (p. 197)! Calvin’s motive was to emphasize Christ as the sole mediator. For him the invocation of the saints is idolatrous (p. 190). Similarly, he condemns relics, religious processions, and miraculous icons.

Now it cannot without effrontery be denied, that when the Reformers appeared he world was more than ever afflicted with this blindness. It was therefore absolutely necessary to urge men with these prophetic rebukes, and divert them, as by force, from that infatuation lest they might any longer imagine that God was satisfied with bare ceremonies, as children are with shows (p. 191; emphasis added).

This leads Calvin to call for the reforming of worship and devotional practices so as to restore what he calls “spiritual worship.” In this particular passage Calvin seems to advocate church reform by preaching and if that did not work by force.

It is hard to know to what extent medieval Roman Catholic devotional practices had fallen into excesses during Calvin’s time but an Orthodox Christian would be taken aback by the sharpness of Calvin’s critique. Praying to the saints is an ancient Christian practice. The Rylands Papyrus 470 which dates to AD 250 contains a prayer to the Virgin Mary asking for her help. The ancient Christian practice of praying to the saints is based on Christ’s resurrection and the communion of saints. While certain bishops sought to temper the excesses in popular piety surrounding the commemoration of the departed the idea of worshipers here below – the church militant — being surrounded by the departed – the church triumphant – became part of the Christian Faith. Excess in popular piety is best held in check through faithful participation in the liturgical life of the Church and submitting to the pastoral care of the priesthood.

Also, in comparison to Roman Catholicism Orthodoxy has been more receptive to the use of the vernacular in the Liturgy. The Church of Rome’s inflexible stance on Latin as the language of worship changed with Vatican II. An Orthodox Christian would find it puzzling that the acceptance of the vernacular was accompanied with a new liturgy, the Novus Ordo Mass. Why not retain the historic Mass but translate it into the local vernacular? This is what is done in many Orthodox parishes in the US. Many Orthodox parishes celebrate the ancient St. John Chrysostom’s Liturgy in English or a mixture of English and non-English.

While not a prominent part of contemporary Reformed-Orthodox dialogue it should be noted that not only does Orthodoxy today continue to venerate icons, we also have relics and miraculous icons. While the danger of fraud exists, Orthodoxy has safeguards to discern the validity of these supernatural manifestations. What is concerning about Calvin’s critique is the way it rejects the sacramental understanding of reality so fundamental to Orthodoxy. Also, concerning is the secularizing effects of Calvin’s position. The Protestant Reformers did not deny the supernatural but confined it to Scripture. For example, the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper were efficacious because of the power of the “Word of God” (signaled by the capitalized form for the Bible) invoked during the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Another implication of Calvin’s emphasis on personal faith is the interiorizing and psychologizing effects on Protestant spirituality. The personal interior dimension of Christianity took priority over the collective ecclesial aspects of the Christian life. Thus, Calvin’s quest to reform prayer comes with a high cost that many Protestants may not be aware of.

The Ground of Salvation

It was justification by faith that sparked the Reformation. When Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses he called into question the practice of selling indulgences. In the ensuing debates the focus shifted to the ground of salvation. The sale of indulgences was based on the Western medieval theory of the church as a treasury of merit and the power of the keys.

They say that by the keys the treasury of the Church is unlocked, so that what is wanting to ourselves is applied out of the merits of Christ and the saints. We on the contrary maintain that the sins of men are forgiven freely, and we acknowledge no other satisfaction than that which Christ accomplished, when, by the sacrifice of his death, he expiated our sins (p. 200).

Much of the debate surrounding justification by faith was framed and constrained by the judicial, forensic paradigm to the exclusion of other soteriological paradigms. While much of Calvin’s rebuttal of his opponents rested on the forensic theory of salvation, one can find a non-forensic understanding of salvation in his writings.

This consideration is of very great practical importance, both in retaining men in the fear of God, that they may not arrogate to their works what proceeds from his fatherly kindness; and also in inspiring them with the best consolation, lest they despond when they reflect on the imperfection or impurity of their works, by reminding them that God, of his paternal indulgence, is pleased to pardon it (p. 202).

Calvin’s emphasis here on God’s paternal love for humanity is surprisingly close to what Orthodoxy affirms.

The issue of the ground of our salvation and the faith versus works tension was never a major issue in Orthodoxy. Unlike Western Christianity, Orthodoxy never went into detail about how we are saved and the means by which we appropriate salvation in Christ. Where Orthodox soteriology remains rooted in patristic theology, medieval Catholicism took a more legal and philosophical turn with unexpected innovations like the sale of indulgences and the understanding of the Church as a treasury of merits. The Orthodox understanding of salvation is informed by the Christus Victor (Christ the Conqueror) motif as is evidenced by the annual Pascha (Easter) service and by the understanding of salvation as union with Christ. The theme of union with Christ is much more intimate and relational than the idea of imputation of Christ’s merits which is more impersonal and transactional in nature. Unlike certain readings of sola fide (justification by faith alone), the Orthodox understanding of the relationship between faith in Christ and good works is more organic and synergistic. We read in Decree 13 of the Confession of Dositheus:

We believe a man to be not simply justified through faith alone, but through faith which works through love, that is to say, through faith and works.

Soteriology is one of the key justifications for the Reformation. In claiming to bring back the Gospel the Protestant Reformers introduced a much more narrow understanding of the Gospel. The debates over justification would be consequential for Protestantism. Justification by faith was elevated into dogma. Some Protestants insist that unless one holds fast to the distinction between imputed righteousness and infused righteousness one will not have a “proper” understanding of the Gospel and if one did not have a “proper” understanding of the Gospel one was not truly a Christian! The early Church on the other hand dogmatized on Christology but remained flexible and ambiguous on how we are saved by Christ. It was not until the medieval Scholasticism introduced these categorical precision that the Catholic versus Protestant debates over justification became a possibility. One unforeseen consequence of these debates is that personal faith in Christ soon became equated with intellectual assent to a particular forensic theory of salvation. Another consequence is that it erects walls between Protestantism and other traditions like Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy being rooted in the church fathers and the Ecumenical Councils would not view the Protestant Reformers’ “rediscovered” Gospel in sola fide (justification by faith alone) as sufficient justification for the Reformation but more as a theological innovation peculiar to the West.

Reforming the Sacraments

For Calvin the reform of the church entailed the reforming of the sacraments, removing man-made additions and returning to the simplicity of biblical worship. This is his justification for reducing the number of sacraments from seven to two. Calvin is reacting to several developments: (1) liturgical additions not found in the Bible, (2) the adoration of the Host, (3) withholding the communion chalice from the laity, and (4) the use of non-vernacular in worship. For Calvin the pastor medieval Catholic worship resulted in the laity being reduced to passive bystanders looking on with dumb incomprehension. Calvin seeks to replace this magical understanding of the sacraments with one based on an intelligent understanding of Scripture in combination with a lively faith in Christ.

Like Calvin modern day Evangelicals hold to two sacraments but many will be surprised by how Calvin understood the sacraments. Calvin did not do away with infant baptism, nor did he insist on total immersion. While Calvin rejected the medieval Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, he did not embrace a purely symbolic understanding of the Lord’s Supper.

Accordingly, in the first place he gives the command, by which he bids us take, eat and drink; and then in the next place he adds and annexes the promise, in which he testifies that what we eat is his body, and what we drink is his blood. . . . . For this promise of Christ, by which he offers his own body and blood under the symbols of bread and wine, belongs to those who receive them at his hand, to celebrate the mystery in the manner which he enjoins (p. 205; emphasis added).

Calvin adopts a view somewhere between the extremes of the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation and the later Protestant Evangelical “just a symbol” understanding of the Lord’s Supper. However, his “under the symbols” seems to implicitly deny that the bread and the wine undergo a change in the Eucharist. It is at odds with the understanding of the early church fathers.

Assessing Calvin’s Apologia

There is a funny story about a Protestant who wanted to convert to Orthodoxy. He runs up to an Orthodox priest and says: “I’m a Protestant, what must I do to become Orthodox?” The priest answered: “You must give up your Roman Catholicism!” The point here is that many of the problems in Protestant doctrine and worship reflect its origins in Roman Catholicism. It also reflects the fact that Western Christianity has broken from its patristic roots in the early Church. Another way of putting it is that Protestants are innocent victims of Rome’s errors and innovations.

To sum up, Calvin justifies the Reformation on three grounds: (1) doctrine, (2) the sacraments, and (3) church government, claiming that the goal was to restore the “old form” using Scripture (i.e., sola scriptura).

Therefore let there be an examination of our whole doctrine, of our form of administering the sacraments, and our method of governing the Church; and in none of these three things will it be found that we have made any change in the old form, without attempting to restore it to the exact standard of the Word of God. (p. 187; emphasis added)

Calvin and the other Reformers had no intention of dividing the Church or of creating a new religion. They desired to bring back the old forms using the Bible as their standard and guide. The results have been quite different from what the Reformers had expected. The next five centuries would see within Protestantism one church split over another, new doctrines, new forms of worship, and even new morality. One interesting statement in Calvin’s apologia is the sharp denunciation of “new worship” (p. 192).

. . . God in many passages forbids any new worship unsanctioned by his Word, declared that he is gravely offended by such audacity, and threatens it with severe punishment, it is clear that the reformation which we have introduced was demanded by a strong necessity” (p. 192; emphasis added).

In light of the fact modern day Protestant worship ranges from so-called traditional organ and hymnal worship that date to the 1700s, to exuberant Pentecostal worship, to seeker friendly services with rock-n-roll style praise bands, to the more liturgical ancient-future worship one has to wonder if the Protestant cure is worse than the disease the Reformers sought to cure!

It is encouraging to see a growing interest among Reformed Christians in the ancient liturgies and the early church fathers. This points to a convergence between two quite different traditions. However, they remain far apart on icons, praying to the saints, and the real presence in the Eucharist. These are not minor points. Calvin’s essay “The Necessity of Reforming the Church” makes clear these are part of the basic rationale for the Reformation.

As Protestantism’s five hundredth anniversary draws near it provides an opportunity for Reformed and Orthodox Christians to assess the Reformation and ask: Was the Reformation Necessary? My answer as an Orthodox Christian is that while the situation of medieval Catholicism in Luther and Calvin’s time may have warranted significant corrective action, the Protestant cure is worse than the disease. For all its adherence to Scripture the Reformed tradition as a whole has failed to recover the “old form” found in ancient Christianity. Its numerous church splits put it at odds with the catholicity and unity of the early Church. Orthodoxy being rooted in the early Church, the Seven Ecumenical Councils, and in Apostolic Tradition has avoided many of the problems that have long plagued Western Christianity. Orthodoxy has never had a Reformation. It has had no need for the Reformation because it has remained rooted in the patristic consensus and because it has resisted the innovations of post-Schism medieval Roman Catholicism. The fact that Orthodoxy has never had a Reformation is something that a Protestant should give thought to.

Already a conversation about the necessity of the Reformation is underway. Three major Reformed leaders: Don Carson, John Piper, and Tim Keller did a videotaped conversation: “Why the Reformation Matters.” The Internet Monk published: “Reformation Week 2015: Another Look – God’s Righteousness.” The Reformed-OrthodoxBridge hopes to provide a space where the two traditions can meet and converse in an atmosphere of civility and charity.

Robert Arakaki

References

Theodore Beza. “Life of John Calvin.”

James Jackson. “The Reformation and Counter-Reformation.”

The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod. “Diets of Speyer.”

J.K.S. Reid, ed. 1954. Calvin: Theological Treatises. The Library of Christian Classics: Ichthus Edition. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Additional Resources

Internet Monk (Chaplain Mike). 2015. “Reformation Week 2015: Another Look – God’s Righteousness.”

The Gospel Coalition. 2015. “Keller, Piper, and Carson on Why the Reformation Matters.”

Ligonier Ministries (Robert Rothwell). 2014. “What is Reformation Day All About?”

Recent Comments