Comments from Two Readers on my article “Evidence for Christ’s Descent into Hell”

David Roxas on 10-June-2018 wrote:

“This is not to say that Protestants and Evangelicals should relinquish the penal model of salvation altogether, but that they should incorporate the ancient patristic model of Christus Victor into their theology.”

Scratching my head over this one. What exactly do you mean the penal mode of salvation should not be relinquished? Should the Orthodox then accept it? Forensic justification by faith alone and penal substitution go hand in hand so how do you propose to separate them if at all? How does penal substitution fit with salvation by participation in the uncreated energies of God (theosis)?

“I believe that there is some merit to the penal theory of atonement and that we need a balanced corrective to the dominant Protestant understanding.”

As Ricky said to Lucy “You got some ‘splainin’ to do!” Please tell us more about what you think the merits of penal theory of the atonement.

Anastasia Gutnik on 14-June-2018 wrote:

I had no idea you were a closet protestant! haha! After 6 years of blogging and you cannot get past penal substitution. that is hilarious Robert!

My Response

I appreciate David and Anastasia’s questions about a statement I made in the article “Evidence for Christ’s Descent into Hell. (6 April 2018)” I am also somewhat amused by their incredulity at my attempt to maintain a charitable openness towards Protestant soteriology. Becoming Orthodox did not entail my rejecting Protestant theology wholesale, but only that which is incompatible with the historic Christian Faith.

How Christ saves us is a tremendous mystery that cannot be reduced to a simple doctrinal formula as many Protestants seem to assume. While both Protestants and Orthodox Christians see great importance in Christ’s death, they approach it very differently. Whereas the Protestant understanding has been shaped by their reaction against medieval Roman Catholicism, the Orthodox understanding has been shaped by the early Church Fathers and the ancient liturgies. Unlike Protestantism, which has well-defined and clearly-articulated statements on how Christ saved us, the early Church had no clear-cut soteriology (McGrath Vol. 1 p. 23; Kelly p. 375). This means that it is difficult to draw a clear-cut black-and-white distinction between Protestant and Orthodox soteriologies. Whereas the Orthodox Church has rejected Protestant doctrines like justification by faith alone and double predestination, there has yet to be a formal condemnation of the theory of penal substitutionary atonement. While there are Orthodox Christians who are very critical of this theory, there are others who are receptive to it. I hope one day to write a more in-depth article on the differences and similarities between the two theological traditions. However, in light of the importance of David and Anastasia’s questions for Reformed-Orthodox dialogue, I believe that I should attempt a brief sketch in this article.

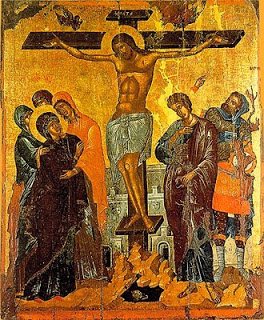

To answer their questions: Yes, Orthodoxy does believe in Christ’s substitutionary death on the Cross, but not in the same way as Protestants do. Below is a sketch of the paradigmatic differences between Protestantism and Orthodoxy over how Christ saves us through his death on the Cross. Then, further down in the article, I cite several contemporary Orthodox apologists—Kabane the Christian, Frederica Mathewes-Green, and Father Josiah Trenham—on their understanding of Christ’s saving death.

Problem – In Protestant theology, the big problem is the guilt that results from our violating the law and God’s wrath against guilty sinners. In Orthodoxy, the big problem is our alienation from God who is Life, and our captivity to the Devil and Death.

Solution – In Protestant theology, the solution is Jesus being punished on our behalf in order to pay the penalty we richly deserve. In Orthodoxy, the solution is Jesus’ dying on the Cross, his descent into Hades, the realm of Death, and his third-day Resurrection, in which the gates of Hell are shattered, captive humans set free from Death, and joined to Christ the Life of the World.

Emphasis – This explains why the key doctrine of Protestantism is justification by faith alone—the word “justification” puts the focus on the legal imputation of guilt, the requisite punishment for that guilt, and the imputation of Christ’s legal righteousness to those who have faith in Christ. In Orthodoxy, this explains why the emphasis is on our union with Christ who is Life, and on faith in Christ as faithfulness to Christ.

I would encourage readers to listen to the two podcasts linked below and to consider purchasing Father Josiah’s excellent book. I have provided a few transcribed remarks with time marks for their convenience.

Kabane the Christian’s “Do Orthodox Christians Believe in Penal Atonement?”

He states forthrightly: “Yes, Orthodox do believe in penal substitution.” [0:21] He also notes that the Church Fathers taught that Christ took the penalty we deserved. [0:53] He then goes on to explain that the penalty we deserve is death, the tearing of the soul from the body.

Kabane notes that in the West, death, which Orthodoxy views as the primary problem, gets shoved to the side and eternal hell is seen as the real punishment even though hell is not mentioned in Genesis 3. [5:20] For the Orthodox, hell is the eternal realization of death. [5:57]

Frederica Mathewes-Green’s “Orthodoxy and the Atonement”

She notes about Orthodoxy: “We just believe that God just forgives us. He doesn’t expect anyone to pay. It isn’t that he gets a third party to pay. He just lets it go.” [5:08] She notes that in the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant (Matthew 18:23-35) the Master forgives; he does not get a third party to pay off the debt owed him. In the Parable of the Prodigal Son the father forgives the son and welcomes him home [5:45]. The father does not demand that the son repay the money squandered (Luke 15:11-32).

Frederica notes that our problem is not so much forgiveness as death. “We have to be rescued. We’ve made ourselves captives of the Evil One. We’ve gotten ourselves enclosed in the prison of death through our sins.” [6:18]

Father Josiah Trenham’s Rock and Sand

Fr. Josiah notes:

The great problem with Protestant teaching on salvation is its thorough-going reductionism. In the Holy Scripture and in the writings of the Holy Fathers salvation is a grand accomplishment with innumerable facets, a great and expansive deliverance of humanity from all its enemies: sin, condemnation, the wrath of God, the devil and his demons, the world, and ultimately death. In Protestant teaching and practice, salvation is essentially a deliverance from the wrath of God. (p. 288; emphasis added)

The traditional Christian teaching expressed in the New Testament and the writings of the Fathers on the subject of the atonement of our Savior is the Cross saved us in three essential ways: on the Cross Jesus conquered death; on the Cross Jesus triumphed over the principalities and power of this evil age; on the Cross Jesus made atonement for human sins by His blood. Because the Protestants were working out of a soteriological framework of a courtroom and declarative justification, they read the teaching about the Cross through these lenses and as a result articulated a reductionistic theology of the atonement, which ignored the traditional emphasis on the conquering of death and the triumph of the demons. Everything for Protestantism becomes satisfaction of God’s justice, and by making one image the whole, even that image became distorted in Protestant articulation. (p. 294)

. . . the greatest reductionism is found in the immense neglect of emphasis upon the heart of the New Testament teaching on salvation as union with Jesus Christ . . . . The theology of the Church bears witness to the fact that the mystery of salvation is accomplished not just on the Cross, but from the very moment of Incarnation when the Only-Begotten and Co-Eternal Son united Himself forever with humanity in the womb of the Virgin Mary, his Most Pure Mother. Salvation as union and communion between God and Man drips from every page of the new Testament and in the writings of Holy fathers. (p. 296; emphasis added)

To be fair, two nineteenth-century Reformed theologians, John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff of the Mercersburg Theology school, sought to highlight the more holistic understanding of salvation within the Reformed tradition. (See my assessment of this small but important movement.) More recently, Anglican bishop N.T. Wright’s writings and some of his Reformed followers in the Federal Vision movement have moved away from this narrow, exclusively legal-forensic view. Sadly, in their attempt to incorporate aspects of patristic theology, they have been charged as heretics by their Reformed brethren for seeking to recover ancient Christianity! (See the Recommended Reading at the bottom which lists several articles about the alternative soteriologies that recently surfaced within the Reformed tradition.)

Conclusion

Oftentimes, when one experiences a feeling of disbelief and incredulity, they will say: “Pardon me. I don’t think I heard you right?” My response to David Roxas and Anastasia Gutnik is: “No. You did not hear me right. You are trying to understand my statements using the black-and-white theological categories that emerged from Protestantism’s conflict with Roman Catholicism in the 1500s.”

David Roxa’s assertion that justification by faith alone and penal substitution go hand-in-hand is an assumption that needs to be scrutinized in light of Scripture and the early Church Fathers’ reading of Scripture. While there is a penal aspect to Christ’s death, how we understand “penal” needs to be scrutinized for hidden assumptions. What also needs to be scrutinized is the centrality of justification (legal righteousness) to our salvation in Christ. Is justification central to salvation or an aspect of salvation? It seems that for Protestants, forensic justification is equivalent to salvation. But is that the case in light of the rich, diverse Scriptural teachings about how Christ saves us? My impression is that in defending sola fide (justification by faith alone) Protestant theology inadvertently ended up suppressing certain passages from their reading of Scripture. This gave rise to a theological paradigm that many Protestants today accept uncritically. It also gave rise to their ignorance of its novelty and sola fide’s being conditioned by medieval Roman Catholicism. If, on the other hand, it is union with Christ that is central to our salvation, of which justification is one aspect, then the penal substitutionary theory does not necessarily preclude theosis. This would address David Roxas’ concern that penal substitutionary atonement is incompatible with theosis – salvation as participation with the uncreated energies of God. This would help correct some of the overemphasis in Protestant theology and help Protestant inquirers integrate the Church Fathers into their understanding of how we are saved by Christ. Furthermore, it would validate my suggestion that a Protestant who wishes to become Orthodox would not necessarily need to relinquish the penal model of salvation provided that he or she seek to understand it within the context of the patristic consensus. Therefore, one need not be a “closet Protestant” as Anastasia Gutnik sarcastically alleged in her comment but in fact a solidly Orthodox Christian.

In closing, I urge David Roxas, Anastasia Gutnik, and other Protestants to be more open to the early Church Fathers who had a richer and more holistic understanding of Christ’s death on the Cross. I also urge them to learn from the ancient Eucharistic prayers that contain valuable insights into how the early Christians understood Christ’s saving death. While the Church Fathers affirmed that Christ died on behalf of sinners and that He paid the penalty we deserved, the judicial emphasis is quite subdued, and other motifs such as redemption and union with Christ are given greater emphasis.

Below are some excerpts from the early Church. In them one will encounter a theological paradigm that is strikingly different from that of Protestantism, which should cause thoughtful Protestants to rethink their theology.

Irenaeus of Lyons, one of the earliest Church Fathers, who died circa 200, wrote:

Since the Lord thus has redeemed us through His own blood, giving His soul for our souls, and His flesh for our flesh, and has also poured out the Spirit of the Father for the union and communion of God and man, imparting indeed God to men by means of the Spirit, and, on the other hand, attaching man to God by His own incarnation, and bestowing upon us at His coming immortality durably and truly, by means of communion with God,—all the doctrines of the heretics fall to ruin. (Irenaeus of Lyons Against Heresies Book 5.1.1, ANF p. 526)

Athanasius the Great, a stalwart defender of Christ’s divinity during the Arian controversy of the fourth century, wrote:

. . . Even so was it with Christ. He, the Life of all, our Lord and Savior, did not arrange the manner of his own death lest He should seem to be afraid of some other kind. No. He accepted and bore upon the cross a death inflicted by others, and those others His special enemies, a death which to them was supremely terrible and by no means to be faced; and He did this in order that, by destroying even this death, He might Himself be believed to be the Life, and the power of death be recognized as finally annulled. (Athanasius the Great On the Incarnation §24)

In the fourth century liturgy of Basil the Great we find this statement in the Eucharistic prayer:

He gave Himself as ransom to death in which we were held captive, sold under sin. Descending into Hades through the cross, that He might fill all things with Himself, He loosed the bonds of death. He rose on the third day, having opened a path for all flesh to the resurrection from the dead, since it was not possible that the Author of life would be dominated by corruption. (Eucharistic prayer – Liturgy of Basil the Great, 4th century)

While not Protestant, the early Church Fathers were undeniably Christian in theology. There is much spiritual wisdom in the Church Fathers that both Protestants as well as Orthodox can benefit from.

Robert Arakaki

References and Recommended Readings

Robert Arakaki. “An Eastern Orthodox Critique of Mercersburg Theology.” OrthodoxBridge (2012)

Athanasius the Great. On the Incarnation.

Basil the Great. Divine Liturgy. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

Jordan Cooper. “Thoughts on Mercersburg Theology.” Just & Sinner (2014)

Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies 5.1.1. Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. 1

J.N.D. Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. 1978 edition.

Alister McGrath. Iustitia Dei: A history of the Christian doctrine of Justification. Vol. 1 The Beginnings to the Reformation.

Matt Powell. “Mercersburg and the Federal Vision.” Aquila Report (2016)

Alastair Roberts. “Approaches to Justification within the Federal Vision.” Alistair’s Adversaria (2006)

Father Josiah Trenham. Rock and Sand. (2015)

Recent Comments