Twenty-First Sunday after Pentecost / Fifth Sunday of Luke, November 2, 2014

Rev. Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, one God. Amen.

Many people who are introduced to the Orthodox Church for the first time, especially if they come from a Protestant background, often have a few matters that strike them as either incomprehensible or outright wrong. For many, the love and veneration we give the Virgin Mary can make them stumble. Others just can’t understand why we fill our churches with icons. Still others rankle at the idea that we should be accountable to a father-confessor.

When I was introduced to Orthodoxy, none of those things was a problem for me. My own special issue was much more doctrinaire, and it’s an issue that has its origins in the 16th century Protestant Reformation in Western Europe. The question is what exactly the relationship is between faith and good works.

When Martin Luther began in Germany what would become a great rebellion against the authority of the Roman Catholic Church, fracturing Europe into numerous religious sects and movements, one of the things that bugged him the most about Rome’s practices was the shape of its piety. Although Rome never officially taught this, the general belief was that doing good works or making monetary donations would buy salvation in the next life or at least time out of Purgatory, that intermediate place of suffering and purgation that Rome teaches is necessary before the faithful can get into Heaven.

As a Protestant in my younger days, I was raised with this idea about Roman Catholics, that they believe you can earn your way into Heaven. (They don’t believe that, by the way.) When I encountered Orthodoxy, and I saw all the rituals, the piety, the monasticism, the pilgrimages, the ornamentation in the churches, and all the many things Orthodox Christians do as part of their practice, I immediately started thinking about faith and works again.

There’s just so much to do in our church. Why do we do it all? Do we think that, if we come to church enough, serve enough years on the parish council, give enough money, work at enough fundraisers, take enough classes, teach enough classes, read enough books, sing enough hymns, believe hard enough, fast enough, say enough Jesus Prayers, go on enough pilgrimages, or buy enough religious articles, somehow, God will count up all our religious points at the end of life and be obligated to let us into Heaven?

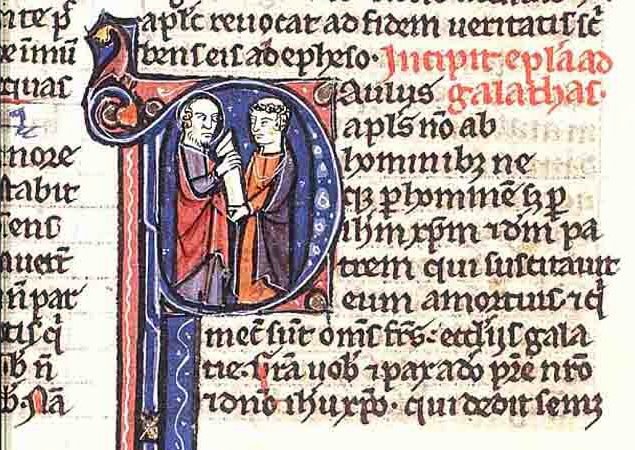

Our patron, the Apostle Paul, writes to the Christians of Galatia something that bears directly on this very question. In the second chapter of this epistle, Paul writes, “knowing that a person is not justified by the works of the Law, but through faith in Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by the works of the Law: for by the works of the Law shall no flesh be justified.” He spells it out clearly: our justification in Christ is by faith, not by the “works of the Law.”

Now, we have to unpack that a little to understand what that means. First, what is Paul talking about when he says “the works of the Law”? He is referring to the Law of Moses, the Jewish Law which was kept by good Jews and included everything from morality to preparing food according to kosher restrictions to ritual washings to rid oneself of ritual impurity.

But when Martin Luther read this section in Galatians, he misread it. He took “the works of the Law” as referring to every good work, not only to the Law of Moses. So he makes faith almost opposed to good works. But that is not what Paul is saying. He is saying that justification comes by faith, not by the Jewish Law.

So we have to ask what “justification” is. Some have taken this word justification to mean essentially “the thing that gets you into Heaven.” If you are “justified,” then you are “saved.” You’ve got your eternal ticket to eternal bliss. But that’s not what justification actually is.

The word used in Greek for “justification” is essentially the same word used for “righteousness.” So if you are “justified,” then you are righteous. If God declares you justified, then you are being declared righteous. And God wouldn’t declare you to be something that you actually aren’t. His declarations are about reality, not legal fictions.

And how does that justification or righteousness come? By faith. And what is faith? It is not only to believe. It cannot be that. Righteousness doesn’t reduce only to what you think is true, even if you’re really passionate about believing it. We must remember that even demons know the truth. They probably know it better than most of us.

Faith is an active, committed holding fast to the object of that faith. For Christians, it is holding fast to Christ. So someone who truly is faithful to Christ is righteous. The point Paul is making is that faithfulness to Christ is not the same thing as faithfulness to the Law of Moses. You can fulfill all the works of that Law yet not be faithful to Christ. It’s only faithfulness to Christ that makes you righteous.

Now if we understand those words faithfulness and righteousness well, then we can see that there is no amount of merely being dutiful that could actually “count” for taking us to eternity with God. It is not that Jews in Paul’s time thought that keeping the Law of Moses got them into Heaven by itself, as though they were earning salvation. It is that they thought that the Law of Moses was the path of righteousness, and that the righteous were justified before God and therefore worthy of Heaven.

So even Jews didn’t believe they earned their way into Heaven. Nowhere do you see in the Jewish Scriptures the idea that doing enough Jewish duties gets you into Heaven. They believed that they could be righteous by following the Law of Moses. Paul is saying that it’s not the Law of Moses that makes you righteous. It’s faithfulness to Christ that does that. He isn’t positing a choice between doing a bunch of religious duties on one hand or believing in Jesus on the other. No, he’s saying that there are two different ways to righteousness, and that one of them is the real way and the other is a dead end and doesn’t actually get you there.

Both ways have both beliefs and actions attached to them. It’s not that one way is about belief and the other about action. It’s that the beliefs and the actions are different between the ways. You have to follow the right way, which includes both belief and action. That is what faith actually entails. It’s not just believing. It’s also acting. You have to believe the right way and also act the right way.

Luther was wrong that the story was “faith versus works.” No, it’s “faith and works” on both sides of the question. The real difference is which faith and works you’re going to follow.

This is why he later says “But if, while we sought to be justified in Christ, we ourselves also were found sinners, is Christ then a minister of sin? God forbid! For if I build up again those things which I destroyed, I prove myself a transgressor. For I through the law died to the law, that I might live to God.” In other words, you can’t pursue righteousness and faithfulness in Christ if what you’re doing is still sinful. You can’t “build up again those things which [you] destroyed”—that is, your sins—and say that that’s the way of Christ. You only prove yourself a transgressor. The way of Christ is not a transgressive way where what you do doesn’t matter so long as you believe the right things. Paul says, yes, “I died to the Law,” but it’s so that he “might live to God.” In other words, he’s not under the Law of Moses any more, but it’s not because he doesn’t care about what he does—it’s because what he does is now about living for God, and that has positive content. It’s a life—a way! It’s about faithfulness and righteousness.

Paul completes this passage with a description of what this looks like: “I have been crucified with Christ, nevertheless I live, yet not I, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave Himself up for me.”

Paul’s been crucified. He’s dead to the world, dead to the Law of Moses. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t do anything, that he now has a life in which good works are irrelevant. No, he is risen with Christ, Who lives in him. Indeed, he says that the life he now lives is not actually his own living but the life of Christ. It is the righteousness and good works and faith of Christ that are now active within him.

So what about all these things that we do in Orthodoxy? Does following the way of Christ rather than the Law of Moses mean that we’re still earning our way to Heaven but only in a different manner? No, it doesn’t mean that. We didn’t replace the Law of Moses with another set of laws.

But the Law of Moses was never about earning your way to Heaven, either. All the good things that Jews did and all the evil Jews refrained from wasn’t about getting enough points to get them into Heaven. It was about training themselves for righteousness. What Paul is saying is that that training doesn’t actually make you righteous. The Law of Moses was good, to be sure, but its point all along was to lead us to crucifixion with Christ so that we could die with Christ and then so we could live in Christ. It was just the roadmap. It wasn’t the destination.

The justification associated with the Law of Moses wasn’t delivered by that Law. Rather, the Law delivered people to Christ, Who is the One Who gives justification, Who makes men righteous.

So we are now alive to Christ. And if we want to remain that way, both now and into eternity, we have to be faithful. We have to be righteous. Our faithfulness and righteousness aren’t what make us worthy of the Kingdom of Heaven. Rather, Christ changes us through those acts to make us like Him. And if we are like Him, then we quite naturally fit into the Kingdom of Heaven.

So let us “live by the faith of the Son of God,” Who loved us and gave Himself up for us. That means faith and action—faithfulness that leads to righteousness.

The Kingdom of Heaven isn’t a place strangers can purchase tickets into by doing good works. It’s a place where Christ-transformed, faithful people who are characterized by good works are welcomed home because they belong there already.

To God therefore be all glory, honor and worship, to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen.

Thank you, thank you, thank you, for writing this article. This is the clearest presentation I have yet found on this subject.

I’m a Protestant (Evangelical, Congregational) who has been soaking up all things Eastern Orthodox for the last year, and attending an Orthodox parish occasionally. I’ve never been able to justify (pardon the pun) the doctrine of Sola Fide in my own mind, but never thought that I might be working from a corrupt glossary of terms.

I was to the point that I hated reading Paul’s epistles because I had heard his words used to support everything from Sola Fide to Five-Point Calvinism (a doctrine that turns my stomach), and couldn’t see a way around it.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that this post is the single most important thing I have read all year.

I wholeheartedly agree with Bryan (that is tough to type when your name is “Byron”). I too am a Protestant and have been learning about Orthodoxy for some time and attending a parish; it is a slow process to change how one thinks, especially about the Bible, but I find I am regularly amazed and enlightened by the wisdom I have found in Orthodox belief.

I would love to see more about some of these foundational, and often misunderstood, teachings.

I also found this very useful, since I’ve been studying Galatians recently and, despite knowing the basic Orthodox understanding, still stumble against the form of St Paul’s argumentation sometimes.

However, I have a minor quibble with your presentation. According to St Chryostom, Gal. 2:17-18 refers to being considered a sinner due to abandoning the Mosaic Law, rather than due to committing various sins after embracing Christian faith. Likewise, building up again what was torn down refers to adopting the Mosaic ordinances after having abandoned or disregarded them (as the Galatians were doing, and as Peter seemed to be doing in Antioch), rather than building up our former sins from before conversion. In this case, the “we were found sinners” in v. 17 would refer back to the gentile sinners in v. 15, i.e. Paul and Peter, by abandoning formal observance of the law, were (according to the argument to be refuted) descending to the level of sinful gentiles.

This is not to claim that your interpretation could nevertheless be valid and helpful as drawing out further consequences of the passage for the life of believers. If you’ve found your interpretation in other exegeses, could you please share the references with me?

To be honest, the best I can offer at this point is either “I remember reading that somewhere” or “it seemed like a decent interpretation to me that is in keeping with the teachings of the Church.” I would certainly not argue with Chrysostom, of course.

Very interesting article. I remember as a small child going to Sunday School and learning about Jesus and his teachings. The Orthodox Church is not all that complicated. It follows closely the teachings of Jesus and his examples set for us to follow. I have strived to do that my whole life, sometimes failing, but always having faith. If I look to Jesus and follow his example I cannot go wrong and will not be confused or distracted. The Orthodox Church is there to help us and guide us on our path to salvation. I do believe that when all else fails, faith and good works do sustain us, after all isn’t that what Jesus was all about? taking care of the sick, the poor, the downtrodden, those with heavy hearts, the hungry etc. Jesus was all about empathy, compassion and love. And showing us the way to everlasting life.

“But when Martin Luther read this section in Galatians, he misread it. He took “the works of the Law” as referring to every good work, not only to the Law of Moses. So he makes faith almost opposed to good works. But that is not what Paul is saying. He is saying that justification comes by faith, not by the Jewish Law.”

Really? Have you even read Luther? It does not sound like you know what you are talking about. Luther considers “law” as all the Law of Moses (civil, ceremonial, and the decalogue). What Luther argues against are the Roman Catholic doctrines of “merit of congruity” and “merit of condignity” not faith being opposed to good works.

——— start

These words, “works of the Law,” are to be taken in the broadest possible sense and are very emphatic. I am saying this because of the smug and idle scholastics and monks, who obscure such words in Paul—in fact, everything in Paul—with their foolish and wicked glosses, which even they themselves do not understand. Therefore take “works of the Law” generally, to mean whatever is opposed to grace: Whatever is not grace is Law, whether it be the Civil Law, the Ceremonial Law, or the Decalog. Therefore even if you were to do the work of the Law, according to the commandment, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, etc.” (Matt. 22:37), you still would not be justified in the sight of God; for a man is not justified by works of the Law. But more detail on this later on.

Thus for Paul “works of the Law” means the works of the entire Law. Therefore one should not make a distinction between the Decalog and ceremonial laws. Now if the work of the Decalog does not justify, much less will circumcision, which is a work of the Ceremonial Law. When Paul says, as he often does, that a man is not justified by the Law or by the works of the Law, which means the same thing in Paul, he is speaking in general about the entire Law; he is contrasting the righteousness of faith with the righteousness of the entire Law, with everything that can be done on the basis of the Law, whether by divine power or by human. For by the righteousness of the Law, he says, a man is not pronounced righteous in the sight of God; but God imputes the righteousness of faith freely through His mercy, for the sake of Christ. It is, therefore, with a certain emphasis and vehemence that he said “by works of the Law,” For there is no doubt that the Law is holy, righteous, and good; therefore the works of the Law are holy, righteous, and good. Nevertheless, a man is not justified in the sight of God through them.

Hence the opinion of Jerome and others is to be rejected when they imagine that here Paul is speaking about the works of the Ceremonial Law, not about those of the Decalog. If I concede this, I am forced to concede also that the Ceremonial Law was good and holy. Surely circumcision and other laws about rites and about the temple were righteous and holy, for they were commanded by God as much as the moral laws were. But then they say: “But after Christ the ceremonial laws were fatal.” They invent this out of their own heads, for it does not appear anywhere in Scripture. Besides, Paul is not speaking here about the Gentiles, for whom the ceremonies would be fatal, but about the Jews, for whom they were good; indeed, he himself observed them. Thus even at the time when the ceremonial laws were holy, righteous, and good, they were not able to justify.

Therefore Paul is speaking not only about a part of the Law, which is also good and holy, but about the entire Law. He means that a work done in accordance with the entire Law does not justify. Nor is he speaking about a sin against the Law or a deed of the flesh, but about “the work of the Law,” that is, a work performed in accordance with the Law. Therefore refraining from murder or adultery—whether this is done by natural powers or by human strength or by free will or by the gift and power of God—still does not justify.

But the works of the Law can be performed either before justification or after justification. Before justification many good men even among the pagans—such as Xenophon, Aristides, Fabius, Cicero, Pomponius Atticus, etc.—performed the works of the Law and accomplished great things. Cicero suffered death courageously in a righteous and good cause. Pomponius was a man of integrity and veracity; for he himself never lied, and he could not bear it if others did. Integrity and veracity are, of course, very fine virtues and very beautiful works of the Law; but these men were not justified by these works. After justification, moreover, Peter, Paul, and all other Christians have done and still do the works of the Law; but they are not justified by them either. “I am not aware of anything against myself,” says Paul; that is, “No man can accuse me, but I am not thereby justified” (1 Cor. 4:4). Thus we see that Paul is speaking about the entire Law and all its works, not about sins against the Law.

Luther, M. (1999, c1963). Vol. 26: Luther’s works, vol. 26 : Lectures on Galatians, 1535, Chapters 1-4 (J. J. Pelikan, H. C. Oswald & H. T. Lehmann, Ed.). Luther’s Works (26:122-124). Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

By his extension of “the works of the Law” to pagans and Christians, Luther is indeed making the misreading I mentioned. He took it in the “broadest” sense, not only in terms of actual Jewish life. The quote given here illustrates exactly the point I’m making.

Another example of how Luther misreads “Law” is that he identified James’ epistle as being entirely “Law” and nothing of the Gospel (and on that basis, he wanted to remove the epistle from the NT). But James isn’t Moses, and he’s writing to Christians, and he’s not a Judaizer.

“It was about training themselves for righteousness. What Paul is saying is that that training doesn’t actually make you righteous. The Law of Moses was good, to be sure, but its point all along was to lead us to crucifixion with Christ so that we could die with Christ and then so we could live in Christ. It was just the roadmap.”

This, if I understand it correctly, mirrors the invitation extended to people to actually take part in Orthodoxy as opposed to studying the Creeds/Doctrines to determine whether to become Orthodox or not. While study and understanding of the creeds and history of the Church is good; participation in the relationship with Christ in His Church is actual salvation. Salvation requires active relationship, not theological prowess, correct?